Politics

- Ahamed, Liaquat. Lords of Finance. New York: Penguin Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-14-311680-6.

- I have become increasingly persuaded that World War I was the singular event of the twentieth century in that it was not only an unprecedented human tragedy in its own right (and utterly unnecessary), it set in motion the forces which would bring about the calamities which would dominate the balance of the century and which still cast dark shadows on our world as it approaches one century after that fateful August. When the time comes to write the epitaph of the entire project of the Enlightenment (assuming its successor culture permits it to even be remembered, which is not the way to bet), I believe World War I will be seen as the moment when it all began to go wrong. This is my own view, not the author's thesis in this book, but it is a conclusion I believe is strongly reinforced by the events chronicled here. The present volume is a history of central banking in Europe and the U.S. from the years prior to World War I through the institution of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates based on U.S. dollar reserves backed by gold. The story is told through the careers of the four central bankers who dominated the era: Montagu Norman of the Bank of England, Émile Moreau of la Banque de France, Hjalmar Schact of the German Reichsbank, and Benjamin Strong of the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Prior to World War I, central banking, to the extent it existed at all in anything like the modern sense, was a relatively dull field of endeavour performed by correspondingly dull people, most aristocrats or scions of wealthy families who lacked the entrepreneurial bent to try things more risky and interesting. Apart from keeping the system from seizing up in the occasional financial panic (which was done pretty much according to the playbook prescribed in Walter Bagehot's Lombard Street, published in 1873), there really wasn't a lot to do. All of the major trading nations were on a hard gold standard, where their paper currency was exchangeable on demand for gold coin or bullion at a fixed rate. This imposed rigid discipline upon national governments and their treasuries, since any attempt to inflate the money supply ran the risk of inciting a run on their gold reserves. Trade imbalances would cause a transfer of gold which would force partners to adjust their interest rates, automatically cooling off overheated economies and boosting those suffering slowdowns. World War I changed everything. After the guns fell silent and the exhausted nations on both sides signed the peace treaties, the financial landscape of the world was altered beyond recognition. Germany was obliged to pay reparations amounting to a substantial fraction of its GDP for generations into the future, while both Britain and France had run up debts with the United States which essentially cleaned out their treasuries. The U.S. had amassed a hoard of most of the gold in the world, and was the only country still fully on the gold standard. As a result of the contortions done by all combatants to fund their war efforts, central banks, which had been more or less independent before the war, became increasingly politicised and the instruments of government policy. The people running these institutions, however, were the same as before: essentially amateurs without any theoretical foundation for the policies this unprecedented situation forced them to formulate. Germany veered off into hyperinflation, Britain rejoined the gold standard at the prewar peg of the pound, resulting in disastrous deflation and unemployment, while France revalued the franc against gold at a rate which caused the French economy to boom and gold to start flowing into its coffers. Predictably, this led to crisis after crisis in the 1920s, to which the central bankers tried to respond with Band-Aid after Band-Aid without any attempt to fix the structural problems in the system they had cobbled together. As just one example, an elaborate scheme was crafted where the U.S. would loan money to Germany which was used to make reparation payments to Britain and France, who then used the proceeds to repay their war debts to the U.S. Got it? (It was much like the “petrodollar recycling” of the 1970s where the West went into debt to purchase oil from OPEC producers, who would invest the money back in the banks and treasury securities of the consumer countries.) Of course, the problem with such schemes is there's always that mountain of debt piling up somewhere, in this case in Germany, which can't be repaid unless the economy that's straining under it remains prosperous. But until the day arrives when the credit card is maxed out and the bill comes due, things are glorious. After that, not so much—not just bad, but Hitler bad. This is a fascinating exploration of a little-known epoch in monetary history, and will give you a different view of the causes of the U.S. stock market bubble of the 1920s, the crash of 1929, and the onset of the First Great Depression. I found the coverage of the period a bit uneven: the author skips over much of the financial machinations of World War I and almost all of World War II, concentrating on events of the 1920s which are now all but forgotten (not that there isn't a great deal we can learn from them). The author writes from a completely conventional wisdom Keynesian perspective—indeed Keynes is a hero of the story, offstage for most of it, arguing that flawed monetary policy was setting the stage for disaster. The cause of the monetary disruptions in the 1920s and the Depression is attributed to the gold standard, and yet even the most cursory examination of the facts, as documented in the book itself, gives lie to this. After World War I, there was a gold standard in name only, as currencies were manipulated at the behest of politicians for their own ends without the discipline of the prewar gold standard. Further, if the gold standard caused the Depression, why didn't the Depression end when all of the major economies were forced off the gold standard by 1933? With these caveats, there is a great deal to be learned from this recounting of the era of the first modern experiment in political control of money. We are still enduring its consequences. One fears the “maestros” trying to sort out the current mess have no more clue what they're doing than the protagonists in this account. In the Kindle edition the table of contents and end notes are properly linked to the text, but source citations, which are by page number in the print edition, are not linked. However, locations in the book are given both by print page number and Kindle “location”, so you can follow them, albeit a bit tediously, if you wish to. The index is just a list of terms without links to their appearances in the text.

- Alinsky, Saul D. Rules for Radicals. New York: Random House, 1971. ISBN 0-679-72113-4.

- Ignore the title. Apart from the last two chapters, which are dated, there is remarkably little ideology here and a wealth of wisdom directly applicable to anybody trying to accomplish something in the real world, entrepreneurs and Open Source software project leaders as well as social and political activists. Alinsky's unrelenting pragmatism and opportunism are a healthy antidote to the compulsive quest for purity which so often ensnares the idealistic in such endeavours.

- Anderson, Brian C. South Park Conservatives. Washington: Regnery Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0-89526-019-0.

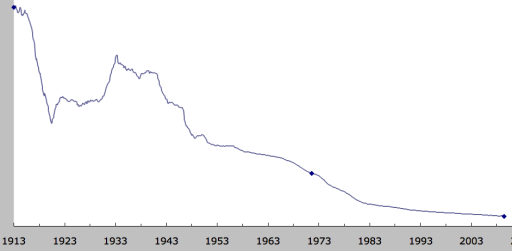

- Who would have imagined that the advent of “new media”—not just the Internet, but also AM radio after having been freed of the shackles of the “fairness doctrine”, cable television, with its proliferation of channels and the advent of “narrowcasting”, along with the venerable old media of stand-up comedy, cartoon series, and square old books would end up being dominated by conservatives and libertarians? Certainly not the greybeards atop the media pyramid who believed they set the agenda for public discourse and are now aghast to discover that the “people power” they always gave lip service to means just that—the people, not they, actually have the power, and there's nothing they can do to get it back into their own hands. This book chronicles the conservative new media revolution of the past decade. There's nothing about the new media in themselves which has made it a conservative revolution—it's simply that it occurred in a society in which, at the outset, the media were dominated by an elite which were in the thrall of a collectivist ideology which had little or no traction outside the imperial districts from which they declaimed, while the audience they were haranguing had different beliefs entirely which, when they found media which spoke to them, immediately started to listen and tuned out the well-groomed, dulcet-voiced, insipid propagandists of the conventional wisdom. One need only glance at the cratering audience figures for the old media—left-wing urban newspapers, television network news, and “mainstream” news-magazines to see the extent to which they are being shunned. The audience abandoning them is discovering the new media: Web sites, blogs, cable news, talk radio, which (if one follows a broad enough selection), gives a sense of what is actually going on in the world, as opposed to what the editors of the New York Times and the Washington Post decide merits appearing on the front page. Of course, the new media aren't perfect, but they are diverse—which is doubtless why collectivist partisans of coercive consensus so detest them. Some conservatives may be dismayed by the vulgarity of “South Park” (I'll confess; I'm a big fan), but we partisans of civilisation would be well advised to party down together under a broad and expansive tent. Otherwise, the bastards might kill Kenny with a rocket widget ball.

- Anderson, Brian C. and Adam D. Thierer. A Manifesto for Media Freedom. New York: Encounter Books, 2008. ISBN 978-1-59403-228-8.

- In the last decade, the explosive growth of the Internet has allowed a proliferation of sources of information and opinion unprecedented in the human experience. As humanity's first ever many-to-many mass medium, the Internet has essentially eliminated the barriers to entry for anybody who wishes to address an audience of any size in any medium whatsoever. What does it cost to start your own worldwide television or talk radio show? Nothing—and the more print-inclined can join the more than a hundred million blogs competing for the global audience's attention. In the United States, the decade prior to the great mass-market pile-on to the Internet saw an impressive (by pre-Internet standards) broadening of radio and television offerings as cable and satellite distribution removed the constraints of over-the-air bandwidth and limited transmission range, and abolition of the “Fairness Doctrine” freed broadcasters to air political and religious programming of every kind. Fervent believers in free speech found these developments exhilarating and, if they had any regrets, they were only that it didn't happen more quickly or go as far as it might. One of the most instructive lessons of this epoch has been that prominent among the malcontents of the new media age have been politicians who mouth their allegiance to free speech while trying to muzzle it, and legacy media outlets who wrap themselves in the First Amendment while trying to construe it as a privilege reserved for themselves, not a right to which the general populace is endowed as individuals. Unfortunately for the cause of liberty, while technologists, entrepreneurs, and new media innovators strive to level the mass communication playing field, it's the politicians who make the laws and write the regulations under which everybody plays, and the legacy media which support politicians inclined to tilt the balance back in their favour, reversing (or at least slowing) the death spiral in their audience and revenue figures. This thin volume (just 128 pages: even the authors describe it as a “brief polemic”) sketches the four principal threats they see to the democratisation of speech we have enjoyed so far and hope to see broadened in unimagined ways in the future. Three have suitably Orwellian names: the “Fairness Doctrine” (content-based censorship of broadcast media), “Network Neutrality” (allowing the FCC's camel nose into the tent of the Internet, with who knows what consequences as Fox Charlie sweeps Internet traffic into the regulatory regime it used to stifle innovation in broadcasting for half a century), and “Campaign Finance Reform” (government regulation of political speech, often implemented in such a way as to protect incumbents from challengers and shut out insurgent political movements from access to the electorate). The fourth threat to new media is what the authors call “neophobia”: fear of the new. To the neophobe, the very fact of a medium's being innovative is presumptive proof that it is dangerous and should be subjected to regulation from which pre-existing media are exempt. Just look at the political entrepreneurs salivating over regulating video games, social networking sites, and even enforcing “balance” in blogs and Web news sources to see how powerful a force this is. And we have a venerable precedent in broadcasting being subjected, almost from its inception unto the present, to regulation unthinkable for print media. The actual manifesto presented here occupies all of a page and a half, and can be summarised as “Don't touch! It's working fine and will evolve naturally to get better and better.” As I agree with that 100%, my quibbles with the book are entirely minor items of presentation and emphasis. The chapter on network neutrality doesn't completely close the sale, in my estimation, on how something as innocent-sounding as “no packet left behind” can open the door to intrusive content regulation of the Internet and the end of privacy, but then it's hard to explain concisely: when I tried five years ago, more than 25,000 words spilt onto the page. Also, perhaps because the authors' focus is on political speech, I think they've underestimated the extent to which, in regulation of the Internet, ginned up fear of what I call the unholy trinity: terrorists, drug dealers, and money launderers, can be exploited by politicians to put in place content regulation which they can then turn to their own partisan advantage. This is a timely book, especially for readers in the U.S., as the incoming government seems more inclined to these kinds of regulations than that it supplants. (I am on record as of July 10th, 2008, as predicting that an Obama administration would re-impose the “fairness doctrine”, enact “network neutrality”, and [an issue not given the attention I think it merits in this book] adopt “hate speech” legislation, all with the effect of stifling [mostly due to precautionary prior restraint] free speech in all new media.) For a work of advocacy, this book is way too expensive given its length: it would reach far more of the people who need to be apprised of these threats to their freedom of expression and to access to information were it available as an inexpensive paperback pamphlet or on-line download. A podcast interview with one of the authors is available.

- Anonymous Conservative [Michael Trust]. The Evolutionary Psychology Behind Politics. Macclenny, FL: Federalist Publications, [2012, 2014] 2017. ISBN 978-0-9829479-3-7.

-

One of the puzzles noted by observers of the contemporary

political and cultural scene is the division of the population

into two factions, (called in the sloppy terminology of the

United States) “liberal” and “conservative”,

and that if you pick a member from either faction by

observing his or her position on one of the divisive issues

of the time, you can, with a high probability of accuracy,

predict their preferences on all of a long list of other issues

which do not, on the face of it, seem to have very much to do

with one another. For example, here is a list of present-day

hot-button issues, presented in no particular order.

- Health care, socialised medicine

- Climate change, renewable energy

- School choice

- Gun control

- Higher education subsidies, debt relief

- Free speech (hate speech laws, Internet censorship)

- Deficit spending, debt, and entitlement reform

- Immigration

- Tax policy, redistribution

- Abortion

- Foreign interventions, military spending

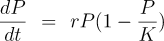

It's a maxim among popular science writers that every equation you include cuts your readership by a factor of two, so among the hardy half who remain, let's see how this works. It's really very simple (and indeed, far simpler than actual population dynamics in a real environment). The left side, “dP/dt” simply means “the rate of growth of the population P with respect to time, t”. On the right hand side, “rP” accounts for the increase (or decrease, if r is less than 0) in population, proportional to the current population. The population is limited by the carrying capacity of the habitat, K, which is modelled by the factor “(1 − P/K)”. Now think about how this works: when the population is very small, P/K will be close to zero and, subtracted from one, will yield a number very close to one. This, then, multiplied by the increase due to rP will have little effect and the growth will be largely unconstrained. As the population P grows and begins to approach K, however, P/K will approach unity and the factor will fall to zero, meaning that growth has completely stopped due to the population reaching the carrying capacity of the environment—it simply doesn't produce enough vegetation to feed any more rabbits. If the rabbit population overshoots, this factor will go negative and there will be a die-off which eventually brings the population P below the carrying capacity K. (Sorry if this seems tedious; one of the great things about learning even a very little about differential equations is that all of this is apparent at a glance from the equation once you get over the speed bump of understanding the notation and algebra involved.) This is grossly over-simplified. In fact, real populations are prone to oscillations and even chaotic dynamics, but we don't need to get into any of that for what follows, so I won't. Let's complicate things in our bunny paradise by introducing a population of wolves. The wolves can't eat the vegetation, since their digestive systems cannot extract nutrients from it, so their only source of food is the rabbits. Each wolf eats many rabbits every year, so a large rabbit population is required to support a modest number of wolves. Now if we go back and look at the equation for wolves, K represents the number of wolves the rabbit population can sustain, in the steady state, where the number of rabbits eaten by the wolves just balances the rabbits' rate of reproduction. This will often result in a rabbit population smaller than the carrying capacity of the environment, since their population is now constrained by wolf predation and not K. What happens as this (oversimplified) system cranks away, generation after generation, and Darwinian evolution kicks in? Evolution consists of two processes: variation, which is largely random, and selection, which is sensitively dependent upon the environment. The rabbits are unconstrained by K, the carrying capacity of their environment. If their numbers increase beyond a population P substantially smaller than K, the wolves will simply eat more of them and bring the population back down. The rabbit population, then, is not at all constrained by K, but rather by r: the rate at which they can produce new offspring. Population biologists call this an r-selected species: evolution will select for individuals who produce the largest number of progeny in the shortest time, and hence for a life cycle which minimises parental investment in offspring and against mating strategies, such as lifetime pair bonding, which would limit their numbers. Rabbits which produce fewer offspring will lose a larger fraction of them to predation (which affects all rabbits, essentially at random), and the genes which they carry will be selected out of the population. An r-selected population, sometimes referred to as r-strategists, will tend to be small, with short gestation time, high fertility (offspring per litter), rapid maturation to the point where offspring can reproduce, and broad distribution of offspring within the environment. Wolves operate under an entirely different set of constraints. Their entire food supply is the rabbits, and since it takes a lot of rabbits to keep a wolf going, there will be fewer wolves than rabbits. What this means, going back to the Verhulst equation, is that the 1 − P/K factor will largely determine their population: the carrying capacity K of the environment supports a much smaller population of wolves than their food source, rabbits, and if their rate of population growth r were to increase, it would simply mean that more wolves would starve due to insufficient prey. This results in an entirely different set of selection criteria driving their evolution: the wolves are said to be K-selected or K-strategists. A successful wolf (defined by evolution theory as more likely to pass its genes on to successive generations) is not one which can produce more offspring (who would merely starve by hitting the K limit before reproducing), but rather highly optimised predators, able to efficiently exploit the limited supply of rabbits, and to pass their genes on to a small number of offspring, produced infrequently, which require substantial investment by their parents to train them to hunt and, in many cases, acquire social skills to act as part of a group that hunts together. These K-selected species tend to be larger, live longer, have fewer offspring, and have parents who spend much more effort raising them and training them to be successful predators, either individually or as part of a pack. “K or r, r or K: once you've seen it, you can't look away.” Just as our island of bunnies and wolves was over-simplified, the dichotomy of r- and K-selection is rarely precisely observed in nature (although rabbits and wolves are pretty close to the extremes, which it why I chose them). Many species fall somewhere in the middle and, more importantly, are able to shift their strategy on the fly, much faster than evolution by natural selection, based upon the availability of resources. These r/K shape-shifters react to their environment. When resources are abundant, they adopt an r-strategy, but as their numbers approach the carrying capacity of their environment, shift to life cycles you'd expect from K-selection. What about humans? At a first glance, humans would seem to be a quintessentially K-selected species. We are large, have long lifespans (about twice as long as we “should” based upon the number of heartbeats per lifetime of other mammals), usually only produce one child (and occasionally two) per gestation, with around a one year turn-around between children, and massive investment by parents in raising infants to the point of minimal autonomy and many additional years before they become fully functional adults. Humans are “knowledge workers”, and whether they are hunter-gatherers, farmers, or denizens of cubicles at The Company, live largely by their wits, which are a combination of the innate capability of their hypertrophied brains and what they've learned in their long apprenticeship through childhood. Humans are not just predators on what they eat, but also on one another. They fight, and they fight in bands, which means that they either develop the social skills to defend themselves and meet their needs by raiding other, less competent groups, or get selected out in the fullness of evolutionary time. But humans are also highly adaptable. Since modern humans appeared some time between fifty and two hundred thousand years ago they have survived, prospered, proliferated, and spread into almost every habitable region of the Earth. They have been hunter-gatherers, farmers, warriors, city-builders, conquerors, explorers, colonisers, traders, inventors, industrialists, financiers, managers, and, in the Final Days of their species, WordPress site administrators. In many species, the selection of a predominantly r or K strategy is a mix of genetics and switches that get set based upon experience in the environment. It is reasonable to expect that humans, with their large brains and ability to override inherited instinct, would be especially sensitive to signals directing them to one or the other strategy. Now, finally, we get back to politics. This was a post about politics. I hope you've been thinking about it as we spent time in the island of bunnies and wolves, the cruel realities of natural selection, and the arcana of differential equations. What does r-selection produce in a human population? Well, it might, say, be averse to competition and all means of selection by measures of performance. It would favour the production of large numbers of offspring at an early age, by early onset of mating, promiscuity, and the raising of children by single mothers with minimal investment by them and little or none by the fathers (leaving the raising of children to the State). It would welcome other r-selected people into the community, and hence favour immigration from heavily r populations. It would oppose any kind of selection based upon performance, whether by intelligence tests, academic records, physical fitness, or job performance. It would strive to create the ideal r environment of unlimited resources, where all were provided all their basic needs without having to do anything but consume. It would oppose and be repelled by the K component of the population, seeking to marginalise it as toxic, privileged, or exploiters of the real people. It might even welcome conflict with K warriors of adversaries to reduce their numbers in otherwise pointless foreign adventures. And K-troop? Once a society in which they initially predominated creates sufficient wealth to support a burgeoning r population, they will find themselves outnumbered and outvoted, especially once the r wave removes the firebreaks put in place when K was king to guard against majoritarian rule by an urban underclass. The K population will continue to do what they do best: preserving the institutions and infrastructure which sustain life, defending the society in the military, building and running businesses, creating the basic science and technologies to cope with emerging problems and expand the human potential, and governing an increasingly complex society made up, with every generation, of a population, and voters, who are fundamentally unlike them. Note that the r/K model completely explains the “crunchy to soggy” evolution of societies which has been remarked upon since antiquity. Human societies always start out, as our genetic heritage predisposes us to, K-selected. We work to better our condition and turn our large brains to problem-solving and, before long, the privation our ancestors endured turns into a pretty good life and then, eventually, abundance. But abundance is what selects for the r strategy. Those who would not have reproduced, or have as many children in the K days of yore, now have babies-a-poppin' as in the introduction to Idiocracy, and before long, not waiting for genetics to do its inexorable work, but purely by a shift in incentives, the rs outvote the Ks and the Ks begin to count the days until their society runs out of the wealth which can be plundered from them. But recall that equation. In our simple bunnies and wolves model, the resources of the island were static. Nothing the wolves could do would increase K and permit a larger rabbit and wolf population. This isn't the case for humans. K humans dramatically increase the carrying capacity of their environment by inventing new technologies such as agriculture, selective breeding of plants and animals, discovering and exploiting new energy sources such as firewood, coal, and petroleum, and exploring and settling new territories and environments which may require their discoveries to render habitable. The rs don't do these things. And as the rs predominate and take control, this momentum stalls and begins to recede. Then the hard times ensue. As Heinlein said many years ago, “This is known as bad luck.” And then the Gods of the Copybook Headings will, with terror and slaughter return. And K-selection will, with them, again assert itself. Is this a complete model, a Rosetta stone for human behaviour? I think not: there are a number of things it doesn't explain, and the shifts in behaviour based upon incentives are much too fast to account for by genetics. Still, when you look at those eleven issues I listed so many words ago through the r/K perspective, you can almost immediately see how each strategy maps onto one side or the other of each one, and they are consistent with the policy preferences of “liberals” and “conservatives”. There is also some rather fuzzy evidence for genetic differences (in particular the DRD4-7R allele of the dopamine receptor and size of the right brain amygdala) which appear to correlate with ideology. Still, if you're on one side of the ideological divide and confronted with somebody on the other and try to argue from facts and logical inference, you may end up throwing up your hands (if not your breakfast) and saying, “They just don't get it!” Perhaps they don't. Perhaps they can't. Perhaps there's a difference between you and them as great as that between rabbits and wolves, which can't be worked out by predator and prey sitting down and voting on what to have for dinner. This may not be a hopeful view of the political prospect in the near future, but hope is not a strategy and to survive and prosper requires accepting reality as it is and acting accordingly.

- Arkes, Hadley. Natural Rights and the Right to Choose. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-521-81218-6.

- Babbin, Jed. Inside the Asylum. Washington: Regnery Publishing, 2004. ISBN 0-89526-088-3.

- You'll be shocked, shocked, to discover, turning these pages, that the United Nations is an utterly corrupt gang of despots, murderers, and kleptocrats, not just ineffectual against but, in some cases, complicit in supporting terrorism, while sanctimoniously proclaiming the moral equivalence of savagery and civilisation. And that the European Union is a feckless, collectivist, elitist club of effete former and wannabe great powers facing a demographic and economic cataclysm entirely of their own making. But you knew that, didn't you? That's the problem with this thin (less than 150 pages of main text) volume. Most of the people who will read it already know most of what's said here. Those who still believe the U.N. to be “the last, best hope for peace” (and their numbers are, sadly, legion—more than 65% of my neighbours in the Canton of Neuchâtel voted for Switzerland to join the U.N. in the March 2002 referendum) are unlikely to read this book.

- Baer, Robert. See No Evil. New York: Crown Publishers, 2002. ISBN 0-609-60987-4.

- Barnett, Thomas P. M. The Pentagon's New Map. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 2004. ISBN 0-399-15175-3.

- This is one scary book—scary both for the world-view it advocates and the fact that its author is a professor at the U.S. Naval War College and participant in strategic planning at the Pentagon's Office of Force Transformation. His map divides the world into a “Functioning Core” consisting of the players, both established (the U.S., Europe, Japan) and newly arrived (Mexico, Russia, China, India, Brazil, etc.) in the great game of globalisation, and a “Non-Integrating Gap” containing all the rest (most of Africa, Andean South America, the Middle East and Central and Southeast Asia), deemed “disconnected” from globalisation. (The detailed map may be consulted on the author's Web site.) Virtually all U.S. military interventions in the years 1990–2003 occurred in the “Gap” while, he argues, nation-on-nation violence within the Core is a thing of the past and needn't concern strategic planners. In the Gap, however, he believes it is the mission of the U.S. military to enforce “rule-sets”, acting preemptively and with lethal force where necessary to remove regimes which block connectivity of their people with the emerging global system, and a U.S.-led “System Administration” force to carry out the task of nation building when the bombs and boots of “Leviathan” (a term he uses repeatedly—think of it as a Hobbesian choice!) re-embark their transports for the next conflict. There is a rather bizarre chapter, “The Myths We Make”, in which he says that global chaos, dreams of an American empire, and the U.S. as world police are bogus argument-enders employed by “blowhards”, which is immediately followed by a chapter proposing a ten-point plan which includes such items as invading North Korea (2), fomenting revolution in (or invading) Iran (3), invading Colombia (4), putting an end to Wahabi indoctrination in Saudi Arabia (5), co-operating with the Chinese military (6), and expanding the United States by a dozen more states by 2050, including the existing states of Mexico (9). This isn't globocop? This isn't empire? And even if it's done with the best of intentions, how probable is it that such a Leviathan with a moral agenda and a “shock and awe” military without peer would not succumb to the imperative of imperium?

- Bartlett, Bruce. Impostor. New York: Doubleday, 2006. ISBN 0-385-51827-7.

- This book is a relentless, uncompromising, and principled attack on the administration of George W. Bush by an author whose conservative credentials are impeccable and whose knowledge of economics and public finance is authoritative; he was executive director of the Joint Economic Committee of Congress during the Reagan administration and later served in the Reagan White House and in the Treasury Department under the first president Bush. For the last ten years he was a Senior Fellow at the National Center for Policy Analysis, which fired him in 2005 for writing this book. Bartlett's primary interest is economics, and he focuses almost exclusively on the Bush administration's spending and tax policies here, with foreign policy, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, social policy, civil liberties, and other contentious issues discussed only to the extent they affect the budget. The first chapter, titled “I Know Conservatives, and George W. Bush Is No Conservative” states the central thesis, which is documented by detailed analysis of the collapse of the policy-making process in Washington, the expensive and largely ineffective tax cuts, the ruinous Medicare prescription drug program (and the shameful way in which its known costs were covered up while the bill was rammed through Congress), the abandonment of free trade whenever there were votes to be bought, the explosion in regulation, and the pork-packed spending frenzy in the Republican controlled House and Senate which Bush has done nothing to restrain (he is the first president since John Quincy Adams to serve a full four year term and never veto a single piece of legislation). All of this is documented in almost 80 pages of notes and source references. Bartlett is a “process” person as well as a policy wonk, and he diagnoses the roots of many of the problems as due to the Bush White House's resembling a third and fourth Nixon administration. There is the same desire for secrecy, the intense value placed on personal loyalty, the suppression of active debate in favour of a unified line, isolation from outside information and opinion, an attempt to run everything out of the White House, bypassing the policy shops and resources in the executive departments, and the paranoia induced by uniformly hostile press coverage and detestation by intellectual elites. Also Nixonesque is the free-spending attempt to buy the votes, at whatever the cost or long-term consequences, of members of groups who are unlikely in the extreme to reward Republicans for their largesse because they believe they'll always get a better deal from the Democrats. The author concludes that the inevitable economic legacy of the Bush presidency will be large tax increases in the future, perhaps not on Bush's watch, but correctly identified as the consequences of his irresponsibility when they do come to pass. He argues that the adoption of a European-style value-added tax (VAT) is the “least bad” way to pay the bill when it comes due. The long-term damage done to conservatism and the Republican party are assessed, along with prospects for the post-Bush era. While Bartlett was one of the first prominent conservatives to speak out against Bush, he is hardly alone today, with disgruntlement on the right seemingly restrained mostly due to lack of alternatives. And that raises a question on which this book is silent: if Bush has governed (at least in domestic economic policy) irresponsibly, incompetently, and at variance with conservative principles, what other potential candidate could have been elected instead who would have been the true heir of the Reagan legacy? Al Gore? John Kerry? John McCain? Steve Forbes? What plausible candidate in either party seems inclined and capable of turning things around instead of making them even worse? The irony, and a fundamental flaw of Empire seems to be that empires don't produce the kind of leaders which built them, or are required to avert their decline. It's fundamentally a matter of crunchiness and sogginess, and it's why empires don't last forever.

- Bastiat, Frédéric. The Law. 2nd. ed. Translated by Dean Russell. Irvington-on-Hudson, NY: Foundation for Economic Education, [1850, 1950] 1998. ISBN 1-57246-073-3.

- You may be able to obtain this book more rapidly directly from the publisher. The original French text, this English translation, and a Spanish translation are available online.

- Bawer, Bruce. While Europe Slept. New York: Doubleday, 2006. ISBN 0-385-51472-7.

- In 1997, the author visited the Netherlands for the first time and “thought I'd found the closest thing to heaven on earth”. Not long thereafter, he left his native New York for Europe, where he has lived ever since, most recently in Oslo, Norway. As an American in Europe, he has identified and pointed out many of the things which Europeans, whether out of politeness, deference to their ruling elites, or a “what-me-worry?” willingness to defer the apocalypse to their dwindling cohort of descendants, rarely speak of, at least in the public arena. As the author sees it, Europe is going down, the victim of multiculturalism, disdain and guilt for their own Western civilisation, and “tolerance for [the] intolerance” of a fundamentalist Muslim immigrant population which, by its greater fertility, “fetching marriages”, and family reunification, may result in Muslim majorities in one or more European countries by mid-century. This is a book which may open the eyes of U.S. readers who haven't spent much time in Europe to just how societally-suicidal many of the mainstream doctrines of Europe's ruling elites are, and how wide the gap is between this establishment (which is a genuine cultural phenomenon in Europe, encompassing academia, media, and the ruling class, far more so than in the U.S.) and the population, who are increasingly disenfranchised by the profoundly anti-democratic commissars of the odious European Union. But this is, however, an unsatisfying book. The author, who has won several awards and been published in prestigious venues, seems more at home with essays than the long form. The book reads like a feature article from The New Yorker which grew to book length without revision or editorial input. The 237 page text is split into just three chapters, putatively chronologically arranged but, in fact, rambling all over the place, each mixing the author's anecdotal observations with stories from secondary sources, none of which are cited, neither in foot- or end-notes, nor in a bibliography. If you're interested in these issues (and in the survival of Western civilisation and Enlightenment values), you'll get a better picture of the situation in Europe from Claire Berlinski's Menace in Europe (July 2006). As a narrative of the experience of a contemporary American in Europe, or as an assessment of the cultural gap between Western (and particularly Northern) Europe and the U.S., this book may be useful for those who haven't experienced these cultures for themselves, but readers should not over-generalise the author's largely anecdotal reporting in a limited number of countries to Europe as a whole.

- Beck, Glenn and Harriet Parke. Agenda 21. New York: Threshold Editions, 2012. ISBN 978-1-4767-1669-5.

- In 1992, at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (“Earth Summit”) in Rio de Janeiro, an action plan for “sustainable development” titled “Agenda 21” was adopted. It has since been endorsed by the governments of 178 countries, including the United States, where it was signed by president George H. W. Bush (not being a formal treaty, it was not submitted to the Senate for ratification). An organisation called Local Governments for Sustainability currently has more than 1200 member towns, cities, and counties in 70 countries, including more than 500 in the United States signed on to the program. Whenever you hear a politician talking about environmental “sustainability” or the “precautionary principle”, it's a good bet the ideas they're promoting can be traced back to Agenda 21 or its progenitors. When you read the U.N. Agenda 21 document (which I highly encourage you to do—it is very likely your own national government has endorsed it), it comes across as the usual gassy international bureaucratese you expect from a U.N. commission, but if you read between the lines and project the goals and mechanisms advocated to their logical conclusions, the implications are very great indeed. What is envisioned is nothing less than the extinction of the developed world and the roll-back of the entire project of the enlightenment. While speaking of the lofty goal of lifting the standard of living of developing nations to that of the developed world in a manner that does not damage the environment, it is an inevitable consequence of the report's assumption of finite resources and an environment already stressed beyond the point of sustainability that the inevitable outcome of achieving “equity” will be a global levelling of the standard of living to one well below the present-day mean, necessitating a catastrophic decrease in the quality of life in developed nations, which will almost certainly eliminate their ability to invest in the research and technological development which have been the engine of human advancement since the Renaissance. The implications of this are so dire that somebody ought to write a dystopian novel about the ultimate consequences of heading down this road. Somebody has. Glenn Beck and Harriet Parke (it's pretty clear from the acknowledgements that Parke is the principal author, while Beck contributed the afterword and lent his high-profile name to the project) have written a dark and claustrophobic view of what awaits at the end of The Road to Serfdom (May 2002). Here, as opposed to an incremental shift over decades, the United States experiences a cataclysmic socio-economic collapse which is exploited to supplant it with the Republic, ruled by the Central Authority, in which all Citizens are equal. The goals of Agenda 21 have been achieved by depopulating much of the land, letting it return to nature, packing the humans who survived the crises and conflict as the Republic consolidated its power into identical densely-packed Living Spaces, where they live their lives according to the will of the Authority and its Enforcers. Citizens are divided into castes by job category; reproductive age Citizens are “paired” by the Republic, and babies are taken from mothers at birth to be raised in Children's Villages, where they are indoctrinated to serve the Republic. Unsustainable energy sources are replaced by humans who have to do their quota of walking on “energy board” treadmills or riding “energy bicycles” everywhere, and public transportation consists of bus boxes, pulled by teams of six strong men. Emmeline has grown up in this grim and grey world which, to her, is way things are, have always been, and always will be. Just old enough at the establishment of Republic to escape the Children's Village, she is among the final cohort of Citizens to have been raised by their parents, who told her very little of the before-time; speaking of that could imperil both parents and child. After she loses both parents (people vanishing, being “killed in industrial accidents”, or led away by Enforcers never to be seen again is common in the Republic), she discovers a legacy from her mother which provides a tenuous link to the before-time. Slowly and painfully she begins to piece together the history of the society in which she lives and what life was like before it descended to crush the human spirit. And then she must decide what to do about it. I am sure many reviewers will dismiss this novel as a cartoon-like portrayal of ideas taken to an absurd extreme. But much the same could have been said of We, Anthem, or 1984. But the thing about dystopian novels based upon trends already in place is that they have a disturbing tendency to get things right. As I observed in my review of Atlas Shrugged (April 2010), when I first read it in 1968, it seemed to evoke a dismal future entirely different from what I expected. When I read it the third time in 2010, my estimation was that real-world events had taken us about 500 pages into the 1168 page tome. I'd probably up that number today. What is particularly disturbing about the scenario in this novel, as opposed to the works cited above, is that it describes what may be a very strong attractor for human society once rejection of progress becomes the doctrine and the population stratifies into a small ruling class and subjects entirely dependent upon the state. After all, that's how things have more or less been over most of human history and around the globe, and the brief flash of liberty, innovation, and prosperity we assume to be the normal state of affairs may simply be an ephemeral consequence of the opening of a frontier which, now having closed, concludes that aberrant chapter of history, soon to be expunged and forgotten. This is a book which begs for one or more sequels. While the story is satisfying by itself, you put it down wondering what happens next, and what is going on outside the confines of the human hive its characters inhabit. Who are the members of the Central Authority? How do they live? How do they groom their successors? What is happening on other continents? Is there any hope the torch of liberty might be reignited? While doubtless many will take fierce exception to the entire premise of the story, I found only one factual error. In chapter 14 Emmeline discovers a photograph which provides a link to the before-time. On it is the word “KODACHROME”. But Kodachrome was a colour slide (reversal) film, not a colour print film. Even if the print that Emmeline found had been made from a Kodachrome slide, the print wouldn't say “KODACHROME”. I did not spot a single typographical error, and if you're a regular reader of this chronicle, you'll know how rare that is. In the Kindle edition, links to documents and resources cited in the factual afterword are live and will take you directly to the cited page.

- Beck, Glenn and Harriet Parke. Agenda 21: Into the Shadows. New York: Threshold Editions, 2015. ISBN 978-1-4767-4682-1.

- When I read the authors' first Agenda 21 (November 2012) novel, I thought it was a superb dystopian view of the living hell into which anti-human environmental elites wish to consign the vast majority of the human race who are to be their serfs. I wrote at the time “This is a book which begs for one or more sequels.” Well, here is the first sequel and it is…disappointing. It's not terrible, by any means, but it does not come up to the high standard set by the first book. Perhaps it suffers from the blahs which often afflict the second volume of a trilogy. First of all, if you haven't read the original Agenda 21 you will have absolutely no idea who the characters are, how they found themselves in the situation they're in at the start of the story, and the nature of the tyranny they're trying to escape. I describe some of this in my review of the original book, along with the factual basis of the real United Nations plan upon which the story is based. As the novel begins, Emmeline, who we met in the previous book, learns that her infant daughter Elsa, with whom she has managed to remain in tenuous contact by working at the Children's Village, where the young are reared by the state apart from their parents, along with other children are to be removed to another facility, breaking this precious human bond. She and her state-assigned partner David rescue Elsa and, joined by a young boy, Micah, escape through a hole in the fence surrounding the compound to the Human Free Zone, the wilderness outside the compounds into which humans have been relocated. In the chaos after the escape, John and Joan, David's parents, decide to also escape, with the intention of leaving a false trail to lead the inevitable pursuers away from the young escapees. Indeed, before long, a team of Earth Protection Agents led by Steven, the kind of authoritarian control freak thug who inevitably rises to the top in such organisations, is dispatched to capture the escapees and return them to the compound for punishment (probably “recycling” for the adults) and to serve as an example for other “citizens”. The team includes Julia, a rookie among the first women assigned to Earth Protection. The story cuts back and forth among the groups in the Human Free Zone. Emmeline's band meets two people who have lived in a cave ever since escaping the initial relocation of humans to the compounds. They learn the history of the implementation of Agenda 21 and the rudiments of survival outside the tyranny. As the groups encounter one another, the struggle between normal human nature and the cruel and stunted world of the slavers comes into focus. Harriet Parke is the principal author of the novel. Glenn Beck acknowledges this in the afterword he contributed which describes the real-world U.N. Agenda 21. Obviously, by lending his name to the project, he increases its visibility and readership, which is all for the good. Let's hope the next book in the series returns to the high standard set by the first.

- Berlinski, Claire. Menace in Europe. New York: Crown Forum, 2006. ISBN 1-4000-9768-1.

- This is a scary book. The author, who writes with a broad and deep comprehension of European history and its cultural roots, and a vocabulary which reminds one of William F. Buckley, argues that the deep divide which has emerged between the United States and Europe since the end of the cold war, and particularly in the last few years, is not a matter of misunderstanding, lack of sensitivity on the part of the U.S., or the personnel, policies, and style of the Bush administration, but deeply rooted in structural problems in Europe which are getting worse, not better. (That's not to say that there aren't dire problems in the U.S. as well, but that isn't the topic here.) Surveying the contemporary scene in the Netherlands, Britain, France, Spain, Italy, and Germany, and tracing the roots of nationalism, peasant revolts (of which “anti-globalisation” is the current manifestation), and anti-Semitism back through the centuries, she shows that what is happening in Europe today is simply Europe—the continent of too many kings and too many wars—being Europe, adapted to present-day circumstances. The impression you're left with is that Europe isn't just the “sick man of the world”, but rather a continent afflicted with half a dozen or more separate diseases, all terminal: a large, un-assimilated immigrant population concentrated in ghettos; an unsustainable welfare state; a sclerotic economy weighed down by social charges, high taxes, and ubiquitous and counterproductive regulation; a collapsing birth rate and aging population; a “culture crash” (my term), where the religions and ideologies which have structured the lives of Europeans for millennia have evaporated, leaving nothing in their place; a near-total disconnect between elites and the general population on the disastrous project of European integration, most recently manifested in the controversy over the so-called European constitution; and signs that the rabid nationalism which plunged Europe into two disastrous wars in the last century and dozens, if not hundreds of wars in the centuries before, is seeping back up through the cracks in the foundation of the dystopian, ill-conceived European Union. In some regards, the author does seem to overstate the case, or generalise from evidence so narrow it lacks persuasiveness. The most egregious example is chapter 8, which infers an emerging nihilist neo-Nazi nationalism in Germany almost entirely based on the popularity of the band Rammstein. Well, yes, but whatever the lyrics, the message of the music, and the subliminal message of the music videos, there is a lot more going on in Germany, a nation of more than 80 million people, than the antics of a single heavy metal band, however atavistic. U.S. readers inclined to gloat over the woes of the old continent should keep in mind the author's observation, a conclusion I had come to long before I ever opened this book, that the U.S. is heading directly for the same confluence of catastrophes as Europe, and, absent a fundamental change of course, will simply arrive at the scene of the accident somewhat later; and that's only taking into account the problems they have in common; the European economy, unlike the American, is able to function without borrowing on the order of two billion dollars a day from China and Japan. If you live in Europe, as I have for the last fifteen years (thankfully outside, although now encircled by, the would-be empire that sprouted from Brussels), you'll probably find little here that's new, but you may get a better sense of how the problems interact with one another to make a real crisis somewhere in the future a genuine possibility. The target audience in the U.S., which is so often lectured by their elite that Europe is so much more sophisticated, nuanced, socially and environmentally aware, and rational, may find this book an eye opener; 344,955 American soldiers perished in European wars in the last century, and while it may be satisfying to say, “To Hell with Europe!”, the lesson of history is that saying so is most unwise. An Instapundit podcast interview with the author is freely available on-line.

- Berman, Morris. The Twilight of American Culture. New York: W. W. Norton, 2000. ISBN 0-393-32169-X.

- Boule, Deplora [pseud.]. The Narrative. Seattle: CreateSpace, 2018. ISBN 978-1-7171-6065-2.

-

When you regard the madness and serial hysterias possessing

the United States: this week “bathroom equality”,

the next tearing down statues, then Russians under every bed,

segueing into the right of military-age unaccompanied male

“refugees” to bring their cultural enrichment to

communities across the land, to proper pronouns for otherkin,

“ripping children” from the arms of their

illegal immigrant parents,

etc., etc., whacky etc., it all seems curiously co-ordinated:

the legacy media, on-line outlets, and the mouths of politicians

of the slaver persuasion all with the same “concerns”

and identical words, turning on a dime from one to the next.

It's like there's a narrative

they're being fed by somebody or -bodies unknown, which they parrot

incessantly until being handed the next talking point to download

into their birdbrains.

Could that really be what's going on, or is it some kind of

mass delusion which afflicts societies where an increasing

fraction of the population, “educated” in

government schools and

Gramsci-converged

higher education, knows nothing of history or the real world

and believes things with the fierce passion of ignorance which

are manifestly untrue? That's the mystery explored in this

savagely hilarious satirical novel.

Majedah Cantalupi-Abromavich-Flügel-Van Der Hoven-Taj Mahal

(who prefers you use her full name, but who henceforth I

shall refer to as “Majedah Etc.”) had become

the very model of a modern media mouthpiece. After reporting

on a Hate Crime at her exclusive women's college while pursuing

a journalism degree with practical studies in Social Change,

she is recruited as a junior on-air reporter by WPDQ, the

local affiliate of News 24/7, the preeminent news network

for good-thinkers like herself. Considering herself ready

for the challenge, if not over-qualified, she informs one

of her co-workers on the first day on the job,

I have a journalism degree from the most prestigious woman's [sic] college in the United States—in fact, in the whole world—and it is widely agreed upon that I have an uncommon natural talent for spotting news. … I am looking forward to teaming up with you to uncover the countless, previously unexposed Injustices in this town and get the truth out.

Her ambition had already aimed her sights higher than a small- to mid-market affiliate: “Someday I'll work at News 24/7. I'll be Lead Reporter with my own Desk. Maybe I'll even anchor my own prime time show someday!” But that required the big break—covering a story that gets picked up by the network in New York and broadcast world-wide with her face on the screen and name on the Chyron below (perhaps scrolling, given its length). Unfortunately, the metro Wycksburg beat tended more toward stories such as the grand opening of a podiatry clinic than those which merit the “BREAKING NEWS” banner and urgent sound clip on the network. The closest she could come to the Social Justice beat was covering the demonstrations of the People's Organization for Perpetual Outrage, known to her boss as “those twelve kooks that run around town protesting everything”. One day, en route to cover another especially unpromising story, Majedah and her cameraman stumble onto a shocking case of police brutality: a white officer ordering a woman of colour to get down, then pushing her to the sidewalk and jumping on top with his gun drawn. So compelling are the images, she uploads the clip with her commentary directly to the network's breaking news site for affiliates. Within minutes it was on the network and screens around the world with the coveted banner. News 24/7 sends a camera crew and live satellite uplink to Wycksburg to cover a follow-up protest by the Global Outrage Organization, and Majedah gets hours of precious live feed directly to the network. That very evening comes a job offer to join the network reporting pool in New York. Mission accomplished!—the road to the Big Apple and big time seems to have opened. But all may not be as it seems. That evening, the detested Eagle Eye News, the jingoist network that climbed to the top of the ratings by pandering to inbred gap-toothed redneck bitter clingers and other quaint deplorables who inhabit flyover country and frequent Web sites named after rodentia and arthropoda, headlined a very different take on the events of the day, with an exclusive interview with the woman of colour from Majedah's reportage. Majedah is devastated—she can see it all slipping away. The next morning, hung-over, depressed, having a nightmare of what her future might hold, she is awakened by the dreaded call from New York. But to her astonishment, the offer still stands. The network producer reminds her that nobody who matters watches Eagle Eye, and that her reportage of police brutality and oppression of the marginalised remains compelling. He reminds her, “you know that the so-called truth can be quite subjective.” The Associate Reporter Pool at News 24/7 might be better likened to an aquarium stocked with the many colourful and exotic species of millennials. There is Mara, who identifies as a female centaur, Scout, a transgender woman, Mysty, Candy, Ångström, and Mohammed Al Kaboom (né James Walker Lang in Mill Valley), each with their own pronouns (Ångström prefers adjutant, 37, and blue). Every morning the pool drains as its inhabitants, diverse in identification and pronomenclature but of one mind (if that term can be stretched to apply to them) in their opinions, gather in the conference room for the daily briefing by the Democratic National Committee, with newsrooms, social media outlets, technology CEOs, bloggers, and the rest of the progressive echo chamber tuned in to receive the day's narrative and talking points. On most days the top priority was the continuing effort to discredit, obstruct, and eventually defeat the detested Republican President Nelson, who only viewers of Eagle Eye took seriously. Out of the blue, a wild card is dealt into the presidential race. Patty Clark, a black businesswoman from Wycksburg who has turned her Jamaica Patty's restaurant into a booming nationwide franchise empire, launches a primary challenge to the incumbent president. Suddenly, the narrative shifts: by promoting Clark, the opposition can be split and Nelson weakened. Clark and Ms Etc have a history that goes back to the latter's breakthrough story, and she is granted priority access to the candidate including an exclusive long-form interview immediately after her announcement that ran in five segments over a week. Suddenly Patty Clark's face was everywhere, and with it, “Majedah Etc., reporting”. What follows is a romp which would have seemed like the purest fantasy prior to the U.S. presidential campaign of 2016. As the campaign progresses and the madness builds upon itself, it's as if Majedah's tether to reality (or what remains of it in the United States) is stretching ever tighter. Is there a limit, and if so, what happens when it is reached? The story is wickedly funny, filled with turns of phrase such as, “Ångström now wishes to go by the pronouns nut, 24, and gander” and “Maher's Syndrome meant a lifetime of special needs: intense unlikeability, intractable bitterness, close-set beady eyes beneath an oversized forehead, and at best, laboring at menial work such as janitorial duties or hosting obscure talk shows on cable TV.” The conclusion is as delicious as it is hopeful. The Kindle edition is free for Kindle Unlimited subscribers. - Bovard, James. Feeling Your Pain. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2000. ISBN 0-312-23082-6.

- Bovard, James. The Bush Betrayal. New York: Macmillan, 2004. ISBN 1-4039-6727-X.

-

Having dissected the depredations of Clinton and Socialist

Party A against the liberty of U.S. citizens in

Feeling Your Pain

(May 2001),

Bovard now turns his crypto-libertarian gaze toward the

ravages committed by Bush and Socialist Party B in the

last four years. Once again, Bovard demonstrates his

extraordinary talent in penetrating the fog of government

propaganda to see the crystalline absurdity lurking within.

On page 88 we discover that under the rules adopted by Colorado

pursuant to the “No Child Left Behind Act”, a school with 1000

students which had a mere 179 or fewer homicides per year would not be

classified as “persistently dangerous”, permitting parents of the

survivors to transfer their children to less target-rich institutions.

On page 187, we encounter this head-scratching poser asked of those

who wished to become screeners for the “Transportation Security

Administration”:

Question: Why is it important to screen bags for IEDs [Improvised Explosive Devices]?

I wish I were making this up. The inspector general of the “Homeland Security Department” declined to say how many of the “screeners” who intimidate citizens, feel up women, and confiscate fingernail clippers and putatively dangerous and easily-pocketed jewelry managed to answer this one correctly. I call Bovard a “crypto-libertarian” because he clearly bases his analysis on libertarian principles, yet rarely observes that any polity with unconstrained government power and sedated sheeple for citizens will end badly, regardless of who wins the elections. As with his earlier books, sources for this work are exhaustively documented in 41 pages of endnotes.- The IED batteries could leak and damage other passenger bags.

- The wires in the IED could cause a short to the aircraft wires.

- IEDs can cause loss of lives, property, and aircraft.

- The ticking timer could worry other passengers.

- Breitbart, Andrew. Righteous Indignation. New York: Grand Central, 2011. ISBN 978-0-446-57282-8.

- Andrew Breitbart has quickly established himself as the quintessential happy warrior in the struggle for individual liberty. His breitbart.com and breitbart.tv sites have become “go to” resources for news and video content, and his ever-expanding constellation of “Big” sites (Big Hollywood, Big Government, Big Journalism, etc.) have set the standard for group blogs which break news rather than just link to or comment upon content filtered through the legacy media. In this book, he describes his personal journey from growing up in “the belly of the beast”—the Los Angeles suburb of Brentwood, his party days at college, and rocky start in the real world, then discovering while watching the Clarence Thomas confirmation hearings on television, that much of the conventional “wisdom” he had uncritically imbibed from the milieu in which he grew up, his education, and the media just didn't make any sense or fit with his innate conception of right and wrong. This caused him to embark upon an intellectual journey which is described here, and a new career in the centre of the New Media cyclone, helping to create the Huffington Post, editing the Drudge Report, and then founding his own media empire and breaking stories which would never have seen the light of day in the age of the legacy media monopoly, including the sting which brought down ACORN. Although he often comes across as grumpy and somewhat hyper in media appearances, I believe Breitbart well deserves the title “happy warrior” because he clearly loves every moment of what he's doing—striding into the lion's den, exploding the lies and hypocrisy of his opponents with their own words and incontrovertible audio and video evidence, and prosecuting the culture war, however daunting the odds, with the ferocity of Churchill's Britain in 1940. He seems to relish being a lightning rod—on his Twitter feed, he “re-tweets” all of the hate messages he receives. This book is substantially more thoughtful than I expected; I went in thinking I'd be reading the adventures of a gadfly-provocateur, and while there's certainly some of that, there is genuine depth here which may be enlightening to many readers. While I can't assume agreement with someone whom I've never met, I came away thinking that Breitbart's view of his opponents is similar to the one I have arrived at independently, as described in Enemies. Breitbart describes a “complex” consisting of the legacy media, the Democrat party, labour unions (particularly those of public employees), academia and the education establishment, and organs of the regulatory state which reinforce one another, ruthlessly suppress opposition, and advance an agenda which is inimical to liberty and the rule of law. I highly recommend this book; it far exceeded my expectations and caused me to think more deeply about several things which were previously ill-formed in my mind. I'll discuss them below, but note that these are my own thoughts and should not be attributed to this book. While reading Breitbart's book, I became aware that the seemingly eternal conflict in human societies is between slavers: people who see others as a collective to be used to “greater ends” (which are usually startlingly congruent with the slavers' own self-interest), and individuals who simply want to be left alone to enjoy their lives, keep the fruits of their labour, not suffer from aggression, and be free to pursue their lives as they wish as long as they do not aggress against others. I've re-purposed Larry Niven's term “slavers” from the known space universe to encompass all of the movements over the tawdry millennia of human history and pre-history which have seen people as the means to an end instead of sovereign beings, whether they called themselves dictators, emperors, kings, Jacobins, socialists, progressives, communists, fascists, Nazis, “liberals”, Islamists, or whatever deceptive term they invent tomorrow after the most recent one has been discredited by its predictably sorry results. Looking at all of these manifestations of the enemy as slavers solves a number of puzzles which might otherwise seem contradictory. For example, why did the American left so seamlessly shift its allegiance from communist dictators to Islamist theocrats who, looked at dispassionately, agree on almost nothing? Because they do agree on one key point: they are slavers, and that resonates with wannabe slavers in a society living the twilight of liberty. Breitbart discusses the asymmetry of the tactics of the slavers and partisans of individual liberty at some length. He argues that the slavers consistently use the amoral Alinsky playbook while their opponents restrict themselves to a more constrained set of tactics grounded in their own morality. In chapter 7, he presents his own “Pragmatic Primer for Realistic Revolutionaries” which attempts to navigate this difficult strait. My own view, expressed more crudely, is that “If you're in a fair fight, your tactics suck”. One of the key tactics of the slavers is deploying the mob into the streets. As documented by Ann Coulter in Demonic, the mob has been an integral part of the slaver arsenal since antiquity, and since the French revolution its use has been consistent by the opponents of liberty. In the United States and, to a lesser extent, in other countries, we are presently seeing the emergence of the “Occupy” movement, which is an archetypal mob composed of mostly clueless cannon fodder manipulated by slavers to their own ends. Many dismiss this latest manifestation of the mob based upon the self-evident vapidity of its members; I believe this to be a mistake. Most mobs in history were populated by people much the same—what you need to look at is the élite vanguard who is directing them and the greater agenda they are advancing. I look at the present manifestation of the mob in the U.S. like the release of a software product. The present “Occupy” protests are the “alpha test”: verifying the concept, communication channels, messaging in the legacy media, and transmission of the agenda from those at the top to the foot soldiers. The “beta test” phase will be August 2012 at the Republican National Convention in Tampa, Florida. There we shall see a mob raised nationwide and transported into that community to disrupt the nomination process (although, if it goes the way I envision infra, this may be attenuated and be smaller and more spontaneous). The “production release” will be in the two weeks running up the general election on November 6th, 2012—that is when the mob will be unleashed nationwide to intimidate voters, attack campaign headquarters, deface advertising messages, and try to tilt the results. Mob actions will not be reported in the legacy media, which will be concentrating on other things. One key take-away from this book for me is just how predictable the actions of the Left are—they are a large coalition of groups of people most of whom (at the bottom) are ill-informed and incapable of critical thinking, and so it takes a while to devise, distribute, and deploy the kinds of simple-minded slogans they're inclined to chant. This, Breitbart argues, makes them vulnerable to agile opponents able to act within their OODA loop, exploiting quick reaction time against a larger but more lethargic opponent. The next U.S. presidential election is scheduled for November 6th, 2012, a little less than one spin around the Sun from today. Let me go out on a limb and predict precisely what the legacy media will be talking about as the final days before the election click off. The Republican contender for the presidency will be Mitt Romney, who will have received, in the entire nomination process, a free pass from legacy media precisely as McCain did in 2008, while taking down each “non-Romney” in turn on whatever vulnerability they can find or, failing that, invent. People seem to be increasingly resigned to the inevitability of Romney as the nominee, and on the Intrade prediction market as I write this, the probability of his nomination is trading at 67.1% with Perry in second place at 8.8%. Within a week of Romney's nomination, the legacy media will, in unison as if led by an invisible hand, pivot to the whole “Mormon thing”, and between August and November 2012, the electorate will be educated through every medium and incessantly until, to those vulnerable to such saturation and without other sources of information, issues such as structural unemployment, confiscatory taxation, runaway regulation, unsustainable debt service and entitlement obligations, monetary collapse, and external threats will be entirely displaced by discussions of golden plates, seer stones, temple garments, the Book of Abraham, Kolob, human exaltation, the plurality of gods, and other aspects of Romney's religion of record, which will be presented so as to cause him to be perceived as a member of a cult far outside the mainstream and unacceptable to the Christian majority of the nation and particularly the evangelical component of the Republican base (who will never vote for Obama, but might be encouraged to stay home rather than vote for Romney). In writing this, I do not intend in any way to impugn Romney's credentials as a candidate and prospective president (he would certainly be a tremendous improvement over the present occupant of that office, and were I a member of the U.S. electorate, I'd be happy affixing a “Romney: He'll Do” bumper sticker to my Bradley Fighting Vehicle), nor do I wish to offend any of my LDS friends. It's just that if, as appears likely at the moment, Romney becomes the Republican nominee, I believe we're in for one of the ugliest religious character assassination campaigns ever seen in the history of the Republic. Unlike the 1960 campaign (which I am old enough to recall), where the anti-Catholic animus against Kennedy was mostly beneath the surface and confined to the fringes, this time I expect the anti-Mormon slander to be everywhere in the legacy media, couched, of course, as “dispassionate historical reporting”. This will, of course, be shameful, but the slavers are shameless. Should Romney be the nominee, I'm simply saying that those who see him as the best alternative to avert the cataclysm of a second Obama term be fully prepared for what is coming in the general election campaign. Should these ugly predictions play out as I envision, those who cherish freedom should be thankful Andrew Breitbart is on our side.

- Brimelow, Peter. Alien Nation. New York: HarperPerennial, 1996. ISBN 0-06-097691-8.

- Brin, David. The Transparent Society. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Books, 1998. ISBN 0-7382-0144-8.

- Having since spent some time pondering The Digital Imprimatur, I find the alternative Brin presents here rather more difficult to dismiss out of hand than when I first encountered it.

- Brink, Anthony. Debating AZT: Mbeki and the AIDS Drug Controversy. Pietermaritzburg, South Africa: Open Books, 2000. ISBN 0-620-26177-3.

- I bought this volume in a bookshop in South Africa; none of the principal on-line booksellers have ever heard of it. The complete book is now available on the Web.

- Buchanan, Patrick J. The Death of the West. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2002. ISBN 0-312-28548-5.

- Buchanan, Patrick J. Day of Reckoning. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2007. ISBN 978-0-312-37696-3.

-

In the late 1980s, I decided to get out of the United States. Why? Because

it seemed to me that for a multitude of reasons, many of which I had experienced

directly as the founder of a job-creating company, resident of a state

whose border the national government declined to defend, and investor who

saw the macroeconomic realities piling up into an inevitable disaster, that

the U.S. was going down, and I preferred to spend the remainder of

my life somewhere which wasn't.

In 1992, the year I moved to Switzerland, Pat Buchanan mounted an insurgent

challenge to George H. W. Bush for the Republican nomination for the U.S.

presidency, gaining more than three million primary votes. His platform

featured protectionism, immigration restriction, and rolling back the

cultural revolution mounted by judicial activism. I opposed most of his

agenda. He lost.

This book can be seen as a retrospective on the 15 years since, and

is particularly poignant to me, as it's a reality check on whether I was wise

in getting out when I did. Bottom line: I've no regrets whatsoever, and

I'd counsel any productive individual in the U.S. to get out as soon as

possible, even though it's harder than when I made my exit.