- Ferrigno, Robert.

Heart of the Assassin.

New York: Scribner, 2009.

ISBN 978-1-4165-3767-0.

-

This novel completes the author's Assassin Trilogy, which began with

Prayers for the Assassin

(March 2006) and continued with

Sins of the Assassin

(March 2008). This is one of those trilogies in which you really

want to read the books in order. While there is some effort

to provide context for readers who start in the middle, you'll miss so much

of the background of the scenario and the development and previous

interactions of characters that you'll miss a great deal of what's

going on. If you're unfamiliar with the world in which these stories

are set, please see my comments on the earlier books in the series.

As this novel opens, a crisis is brewing as a heavily armed and

increasingly expansionist Aztlán is ready to exploit the

disunity of the Islamic Republic and the Bible Belt, most of whose

military forces are arrayed against one another, to continue to nibble

away at both. Visionaries on both sides imagine a reunification of

the two monotheistic parts of what were once the United States, while

the Old One and his mega-Machiavellian daughter Baby work their dark

plots in the background. Former fedayeen shadow warrior Rakkim Epps

finds himself on missions to the darkest part of the Republic, New

Fallujah (the former San Francisco), and to the radioactive remains of

Washington D.C., seeking a relic which might have the power to unite

the nation once again.

Having read and tremendously enjoyed the first two books of the

trilogy, I was very much looking forward to this novel, but

having now read it, I consider it a disappointment. As the

trilogy has progressed, the author seems to have become ever more

willing to invent whatever technology he needs at the moment

to advance the plot, whether or not it is plausible or consistent

with the rest of the world he has created, and to admit the

supernatural into a story which started out set in a world of

gritty reality. I spent the first 270 pages making increasingly

strenuous efforts to suspend disbelief, but then when one of

the characters uses a medical oxygen tank as a flamethrower,

I “lost it” and started laughing out loud at each of

the absurdities in the pages that followed: “DNA knives”

that melt into a person's forearm, holodeck hotel rooms with

faithful all-senses stimulation and simulated lifeforms,

a ghost, miraculous religious relics, etc., etc. The first two

books made the reader think about what it would be like if a

post-apocalyptic Great Awakening reorganised the U.S. around Islamic

and Christian fundamentalism. In this book, all of that is swept into

the background, and it's all about the characters (who one ceases to

care much about, as they become increasingly comic book like) and a

political plot so preposterous it makes Dan Brown's novels seem

like nonfiction.

If you've read the first two novels and want to discover

how it all comes out, you will find all of the threads

resolved in this book. For me, there were just too many

“Oh come on, now!” moments for the result to be

truly satisfying.

A podcast

interview with the author is available.

You can read the first chapter of this book online at the

author's Web site.

- Vallee, Jacques.

Forbidden Science. Vol. 2.

San Francisco: Documatica Research, 2008.

ISBN 978-0-615-24974-2.

-

This, the second volume of

Jacques Vallee's journals,

chronicles the years from 1970 through 1979. (I read the

first volume, covering

1957–1969, before I began this list.) Early in the narrative

(p. 153), Vallee becomes a U.S. citizen, but although

surrendering his French passport, he never gives up his Gallic

rationalism and scepticism, both of which serve him well in the

increasingly weird Northern California scene in the Seventies. It was

in those locust years that the seeds for the personal computing and

Internet revolutions matured, and Vallee was at the nexus of this

technological ferment, working on databases, Doug Englebart's

Augmentation project, and later systems for conferencing and

collaborative work across networks. By the end of the decade he, like

many in Silicon Valley of the epoch, has become an entrepreneur,

running a company based upon the conferencing technology he

developed. (One amusing anecdote which indicates how far we've come

since the 70s in mindset is when he pitches his conferencing system to

General Electric who, at the time, had the largest commercial data

network to support their timesharing service. They said they were

afraid to implement anything which looked too much like a messaging

system for fear of running afoul of the Post Office.)

If this were purely a personal narrative of the formative

years of the Internet and personal computing, it would

be a valuable book—I was there, then, and Vallee

gets it absolutely right. A journal is, in many ways,

better than a history because you experience the groping

for solutions amidst confusion and ignorance which is

the stuff of real life, not the narrative of an historian

who knows how it all came out. But in addition to being

a computer scientist, entrepreneur, and (later)

venture capitalist, Vallee is also one of the

preeminent researchers into the UFO and related

paranormal phenomena (the character Claude Lacombe,

played by François Truffaut in Steven Spielberg's

1977 movie

Close Encounters of the Third Kind

was based upon Vallee). As the 1970s progress, the author

becomes increasingly convinced that the UFO phenomenon cannot

be explained by extraterrestrials and spaceships, and that it is

rooted in the same stratum of the human mind and the universe

we inhabit which has given rise to folklore about little

people and various occult and esoteric traditions. Later in the decade,

he begins to suspect that at least some UFO activity is

the work of deliberate manipulators bent on creating an

irrational, anti-science worldview in the general populace,

a hypothesis expounded in his 1979 book,

Messengers of Deception,

which remains controversial three decades after its

publication.

The Bay Area in the Seventies was a kind of cosmic vortex of

the weird, and along with Vallee we encounter many of the

prominent figures of the time, including

Uri Geller

(who Vallee immediately dismisses as a charlatan),

Doug Engelbart,

J. Allen Hynek,

Anton LaVey,

Russell Targ,

Hal Puthoff,

Ingo Swann,

Ira Einhorn,

Tim Leary,

Tom Bearden,

Jack Sarfatti,

Melvin Belli,

and many more. Always on a relentlessly rational even keel, he

observes with dismay as many of his colleagues disappear

into drugs, cults, gullibility, pseudoscience, and fads

as that dark decade takes its toll. In May 1979

he feels himself to be at “the end of an age that defied

all conventions but failed miserably to set new standards”

(p. 463). While this is certainly spot on in the social and

cultural context in which he meant it, it is ironic that so many

of the standards upon which the subsequent explosion of computer

and networking technology are based were created in those years

by engineers patiently toiling away in Silicon Valley amidst all

the madness.

An introduction and retrospective at the end puts the work into

perspective from the present day, and 25 pages of end notes expand

upon items in the journals which may be obscure at this remove and

provide source citations for events and works mentioned. You might

wonder what possesses somebody to read more than five hundred pages of

journal entries by somebody else which date from thirty to forty years

ago. Well, I took the time, and I'm glad I did: it perfectly

recreated the sense of the times and of the intellectual and

technological challenges of the age. Trust me: if you're too young to

remember the Seventies, it's far better to experience those years here

than to have actually lived through them.

- Woodbury, David O.

The Glass Giant of Palomar.

New York: Dodd, Mead, [1939, 1948] 1953.

LCCN 53000393.

-

I originally read this book when I was in junior high school—it

was one of the few astronomy titles in the school's library. It's

one of the grains of sand dropping on the pile which eventually

provoked the avalanche that persuaded me I was living in

the

golden age of engineering

and that I'd best spend my life

making the most of it.

Seventy years after it was originally published

(the 1948 and 1953 updates added only minor information on the

final commissioning of the telescope and a collection of photos

taken through it), this book still inspires respect for those who

created the 200 inch

Hale Telescope

on Mount Palomar, and the engineering challenges they faced and

overcame in achieving that milestone in astronomical instrumentation.

The book is as much a biography of

George

Ellery Hale as it is a story of the giant telescope he brought

into being. Hale was a world class scientist: he invented the

spectroheliograph, discovered the magnetic fields of sunspots,

founded the Astrophysical Journal and to a large

extent the field of astrophysics itself, but he also excelled

as a promoter and fund-raiser for grand-scale scientific instrumentation.

The

Yerkes,

Mount Wilson,

and

Palomar

observatories would, in all likelihood, not have existed were it not

for Hale's indefatigable salesmanship. And this was an age when

persuasiveness was all. With the exception of the road to the top

of Palomar, all of the observatories and their equipment promoted

by Hale were funded without a single penny of taxpayer money. For

the Palomar 200 inch, he raised US$6 million in gold-backed 1930

dollars, which in present-day paper funny-money amounts to

US$78 million.

It was a very different America which built the Palomar telescope.

Not only was it never even thought of that money coercively taken from

taxpayers would be diverted to pure science, anybody who wanted to

contribute to the project, regardless of their academic credentials,

was judged solely on their merits and given a position based upon

their achievements. The chief optician who ground, polished, and figured

the main mirror of the Palomar telescope (so perfectly that its

potential would not be realised until recently thanks to

adaptive optics)

had a sixth grade education and was first employed at Mount Wilson as a

truck driver. You can make of yourself what you have within yourself

in America, so they say—so it was for

Marcus Brown

(p. 279).

Milton Humason

who, with

Edwin Hubble,

discovered the expansion of the universe, dropped out of school at the

age of 14 and began his astronomical career driving supplies up Mount

Wilson on mule trains. You can make of yourself what you have within

yourself in America, or at least you could then. Now we go elsewhere.

Is there anything

Russell W. Porter

didn't do? Arctic explorer, founder of the hobby of amateur telescope

making, engineer, architect…his footprints and brushstrokes are

all over technological creativity in the first half of the twentieth

century. And he is much in evidence here: recruited in 1927, he did the

conceptual design for most of the buildings of the observatory, and his

cutaway drawings of the mechanisms of the telescope demonstrate to those endowed

with contemporary computer graphics tools that the eye of the artist is

far more important than the technology of the moment.

This book has been out of print for decades, but used copies

(often, sadly, de-accessioned by public libraries) are generally

available at prices (unless you're worried about cosmetics

and collectability) comparable to present-day hardbacks. It's as

good a read today as it was in 1962.

- Dewar, James with Robert Bussard.

The Nuclear Rocket.

Burlington, Canada: Apogee Books, 2009.

ISBN 978-1-894959-99-5.

-

Let me begin with a few comments about the author attribution of

this book. I have cited it as given on the copyright page, but

as James Dewar notes in his preface, the main text of the book

is entirely his creation. He says of Robert Bussard, “I

am deeply indebted to Bob's contributions and consequently list

his name in the credit to this book”. Bussard himself

contributes a five-page introduction in which he uses,

inter alia,

the adjectives “amazing”, “strange”,

“remarkable”, “wonderful”, “visionary”,

and “most odd” to describe the work, which he makes clear

is entirely Dewar's. Consequently, I shall subsequently use “the

author” to denote Dewar alone. Bussard died in 2007,

two years before the publication of this book, so his introduction

must have been based upon a manuscript. I leave to the reader to judge the

propriety of posthumously naming as co-author a

prominent individual who did not write a single word of the main text.

Unlike the author's earlier

To the End of the Solar System (June 2008),

which was a nuts and bolts history of the U.S. nuclear rocket

program, this book, titled The Nuclear Rocket,

quoting from Bussard's introduction, “…is not really

about nuclear rocket propulsion or its applications to space

flight…”. Indeed, although some of the nitty-gritty of

nuclear rocket engines are discussed, the bulk of the book is

an argument for a highly-specific long term plan to transform

human access to space from an elitist government run program to

a market-driven expansive program with the ultimate goal of

providing access to space to all and opening the solar system to

human expansion and eventual dominion. This is indeed ambitious

and visionary, but of all of Bussard's adjectives, the one that sticks

with me is “most odd”.

Dewar argues that the

NERVA B-4 nuclear

thermal rocket core, developed between 1960 and 1972, and

successfully tested on several occasions, has the capability,

once the “taboo” against using nuclear engines in

the boost to low Earth orbit (LEO) is discarded, of revolutionising

space transportation and so drastically reducing the cost per

unit mass to orbit that it would effectively democratise access to

space. In particular, he proposes a “Re-core” engine

which, integrated with a liquid hydrogen tank and solid rocket

boosters, would be air-launched from a large cargo aircraft such

as a

C-5, with the

solid rockets boosting the nuclear engine to around 30 km

where they would separate for recovery and the nuclear engine engaged.

The nuclear rocket would continue to boost the payload to

orbital insertion. Since the nuclear stage would not go critical

until having reached the upper atmosphere, there would be no

radioactivity risk to those handling the stage on the ground prior

to launch or to the crew of the plane which deployed the rocket.

After reaching orbit, the payload and hydrogen tank would be separated,

and the nuclear engine enclosed in a cocoon (much like an

ICBM reentry vehicle) which would de-orbit and eventually land at

sea in a region far from inhabited land. The cocoon, which would float

after landing, would be recovered by a ship, placed in a radiation-proof

cask, and returned to a reprocessing centre where the highly radioactive

nuclear fuel core would be removed for reprocessing (the entire launch to

orbit would consume only about 1% of the highly enriched uranium in the

core, so recovering the remaining uranium and reusing it is essential

to the economic viability of the scheme). Meanwhile, another never

critical core would be inserted in the engine which, after inspection of

the non-nuclear components, would be ready for another flight. If

each engine were reused 100 times, and efficient fuel reprocessing

were able to produce new cores economically, the cost for each

17,000 pound payload to LEO would be around US$108 per pound.

Payloads which reached LEO and needed to go beyond (for example, to

geostationary orbit, the Moon, or the planets) would rendezvous with

a different variant of the NERVA-derived engine, dubbed the

“Re-use” stage, which is much like Von Braun's

nuclear

shuttle concept. This engine, like the original NERVA, would be

designed for multiple missions, needing only inspection and refuelling

with liquid hydrogen. A single Re-use stage might complete 30 round-trip

missions before being disposed of in deep space (offering “free

launches” for planetary science missions on its final trip into the

darkness).

There is little doubt that something like this is technically

feasible. After all, the nuclear rocket engine was extensively

tested in the years prior to its cancellation in 1972, and NASA's

massive resources of the epoch examined mission profiles (under the

constraint that nuclear engines could be used only for

departure from LEO, however, and without return to Earth) and

found no show stoppers. Indeed, there is evidence that the nuclear

engine was cancelled, in part, because it was performing so well

that policy makers feared it would enable additional costly

NASA missions post-Apollo. There are some technological

issues: for example, the author implies that the recovered

Re-core, once its hot core is extracted and a new pure uranium

core installed, will not be radioactive and hence safe to handle

without special precautions. But what about neutron activation

of other components of the engine? An operating nuclear rocket

creates one of the most extreme neutronic environments outside

the detonation of a nuclear weapon. Would it be possible to choose

materials for the non-core components of the engine which would

be immune to this and, if not, how serious would the induced

radioactivity be, especially if the engine were reused up to

a hundred times? The book is silent on this and a number of other

questions.

The initial breakthrough in space propulsion from the first generation

nuclear engines is projected to lead to rapid progress in optimising

them, with four generations of successively improved engines within a

decade or so. This would eventually lead to the development of a

heavy lifter able to orbit around 150,000 pounds of payload per flight

at a cost (after development costs are amortised or expensed) of

about US$87 per pound. This lifter would allow the construction of

large space stations and the transport of people to them in

“buses” with up to thirty passengers per mission. Beyond

that, a nuclear single stage to orbit vehicle is examined, but there

are a multitude of technological and policy questions to be resolved

before that could be contemplated.

All of this, however, is not what the book is about.

The author is a passionate believer in the proposition that opening

the space frontier to all the people of Earth, not just a few

elite civil servants, is essential to preserving peace, restoring

the optimism of our species, and protecting the thin biosphere of

this big rock we inhabit. And so he proposes a detailed structure

for accomplishing these goals, beginning with “Democratization

of Space Act” to be adopted by the U.S. Congress, and the

creation of a “Nuclear Rocket Development and Operations

Corporation” (NucRocCorp), which would be a kind of private/public

partnership in which individuals could invest. This company could

create divisions (in some cases competing with one another) and

charter development projects. It would entirely control space

nuclear propulsion, with oversight by U.S. government regulatory

agencies, which would retain strict control over the fissile

reactor cores.

As the initial program migrated to the heavy lifter, this structure

would morph into a multinational (admitting only “good”

nations, however) structure of bewildering (to this engineer)

bureaucratic complexity which makes the United Nations look like

the student council of

Weemawee High. The lines of responsibility

and power here are diffuse in the extreme. Let me simply cite

“The Stockholder's Declaration” from p. 161:

Whoever invests in the NucRocCorp and subsequent Space Charter

Authority should be required to sign a declaration that commits

him or her to respect the purpose of the new regime, and conduct

their personal lives in a manner that recognizes the rights of

their fellow man (What about woman?—JW). They must be made

aware that failure to do so could result in forfeiture of their

investment.

Property rights, anybody? Thought police? Apart from the manifest

baroque complexity of the proposed scheme, it entirely ignores

Jerry Pournelle's

Iron

Law of Bureaucracy:

regardless of its original mission, any bureaucracy will eventually

be predominately populated by those seeking to advance the interests of

the bureaucracy itself, not the purpose for which it was created. The

structure proposed here, even if enacted (implausible in the extreme)

and even if it worked as intended (vanishingly improbable), would

inevitably be captured by the Iron Law and become something like, well,

NASA.

On pp. 36–37, the author likens attempts to stretch

chemical rocket technology to its limits to gold plating a nail

when what is needed is a bigger hammer (nuclear rockets). But

this book brings to my mind another epigram: “When all

you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” Dewar

passionately supports nuclear rocket technology and believes that

it is the way to open the solar system to human settlement. I

entirely concur. But when it comes to assuming that boosting people

up to a space station (p. 111):

And looking down on the bright Earth and into the black

heavens might create a new perspective among Protestant,

Roman Catholic, and Orthodox theologians, and perhaps lead

to the end of the schism plaguing Christianity. The same might

be said of the division between the Sunnis and Shiites in

Islam, and the religions of the Near and Far East might benefit

from a new perspective.

Call me cynical, but I'll wager this particular swing of the

hammer is more likely to land on a thumb than the intended nail.

Those who cherish individual freedom have often dreamt of a

future in which the opening of access to space would, in the words of

L. Neil Smith, extend

the human prospect to “freedom, immortality, and the

stars”—works

for me. What is proposed here, if adopted, looks more like, after

more than a third of a century of dithering, the space frontier being

finally opened to the brave pioneers ready to homestead there, and

when they arrive, the tax man and the all-pervasive regulatory state

are already there, up and running. The nuclear rocket

can expand the human presence throughout the solar system.

Let's just hope that when humanity (or some risk-taking subset of it)

takes that long-deferred step, it does not propagate the soft tyranny

of present day terrestrial governance to worlds beyond.

- Derbyshire, John.

We Are Doomed.

New York: Crown Forum, 2009.

ISBN 978-0-307-40958-4.

-

In this book, genial curmudgeon

John Derbyshire,

whose

previous two books were popular treatments of the

Riemann hypothesis and the

history of algebra, argues that

an authentically conservative outlook on life requires

a relentlessly realistic pessimism about human

nature, human institutions, and the human prospect.

Such a pessimistic viewpoint immunises one from the

kind of happy face optimism which breeds enthusiasm

for breathtaking ideas and grand, ambitious schemes,

which all of history testifies are doomed to

failure and tragedy.

Adopting a pessimistic attitude is, Derbyshire says,

not an effort to turn into a sourpuss (although see

the photograph of the author on the

dust jacket), but simply the consequence of removing

the rose coloured glasses and looking at the world as

it really is. To grind down the reader's optimism into

a finely-figured speculum of gloom, a sequence of

chapters surveys the Hellbound landscape of what passes

for the modern world: “diversity”, politics,

popular culture, education, economics, and third-rail

topics such as achievement gaps between races and

the assimilation of immigrants. The discussion is

mostly centred on the United States, but in chapter 11,

we take a

tour d'horizon and find

that things are, on the whole, as bad or worse everywhere

else.

In the conclusion the author, who is just a few years my senior,

voices a thought which has been rattling around my own brain for some

time: that those of our generation living in the West may be seen, in

retrospect, as having had the good fortune to live in a golden age. We just

missed the convulsive mass warfare of the 20th century (although not,

of course, frequent brushfire conflicts in which you can be killed

just as dead, terrorism, or the threat of nuclear annihilation during

the Cold War), lived through the greatest and most broadly-based

expansion of economic prosperity in human history, accompanied by more

progress in science, technology, and medicine than in all of the human

experience prior to our generation. Further, we're probably going to

hand

in our dinner pails

before the

economic apocalypse

made inevitable by the pyramid of paper money and bogus debt we

created, mass human migrations, demographic collapse, and the ultimate

eclipse of the tattered remnants of human liberty by the malignant

state. Will people decades and centuries hence look back at the

Boomer generation as the one that reaped all the benefits for themselves

and passed on the bills and the adverse consequences to their

descendants? That's the way to bet.

So what is to be done? How do we turn the ship around before

we hit the iceberg?

Don't look for any such chirpy suggestions here: it's all

in the title—we are doomed! My own view

is that we're in a race between a

technological singularity

and a new

dark age

of poverty, ignorance, subjugation to the state, and pervasive

violence. Sharing the author's proclivity for pessimism, you can

probably guess which I judge more probable. If you concur, you

might want to read

this book,

which will appear in this chronicle in due time.

The book includes neither bibliography nor index. The lack

of the former is particularly regrettable as a multitude

of sources are cited in the text, many available online. It would

be wonderful if the author posted a bibliography of clickable

links (to online articles or purchase links for books cited)

on his

Web site,

where there is a

Web log

of comments from readers and the author's responses.

- Paul, Ron.

End the Fed.

New York: Grand Central, 2000.

ISBN 978-0-446-54919-6.

-

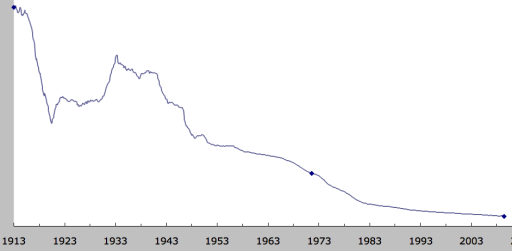

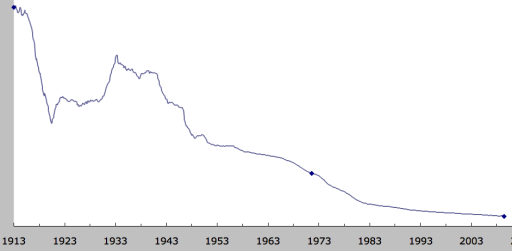

Imagine a company whose performance, measured over almost a century

by the primary metric given in its charter, looked

like this:

Now, would you be likely, were your own personal prosperity and that of all of

those around you on the line, to entrust your financial future to their

wisdom and demonstrated track record? Well, if you live in the United States, or

your finances are engaged in any way in that economy (whether as an investor,

creditor, or trade partner), you are, because this is the chart of

the purchasing power of the United States Dollar since it began to be managed

by the Federal Reserve System in 1913. Helluva record, don't you think?

Now, if you know anything about

basic economics

(which puts you several rungs up the ladder from most present-day

politicians and members of the chattering classes), you'll recall that

inflation is not defined as rising prices but rather an increase in the

supply of money. It's just as if you were at an auction and you gave all of

the bidders 10% more money: the selling price of the item would be 10%

greater, not because it had appreciated in value but simply because the

bidders had more to spend on acquiring it. And what is, fundamentally, the

function of the Federal Reserve System? Well, that would be to implement

an “elastic currency”, decoupled from real-world measures of

value, with the goal of smoothing out the business cycle. Looking at this

shorn of all the bafflegab, the mission statement is to create paper money

out of thin air in order to fund government programs which the legislature lacks

the spine to fund from taxation or debt, and to permit banks to profit by

extending credit well beyond the limits of prudence, knowing they're backed up

by the “lender of last resort” when things go South. The Federal

Reserve System is nothing other than an engine of inflation (money creation),

and it's hardly a surprise that the dollars it issues have lost more than 95%

of their value in the years since its foundation.

Acute observers of the economic scene have been warning about the

risks of such a system for decades—it came onto my personal

radar well before there was a human bootprint on the Moon. But somehow,

despite dollar crises, oil shocks, gold and silver bubble markets, saving and

loan collapse, dot.bomb, housing bubble, and all the rest, the wise money guys

somehow kept all of the balls in the air—until they didn't. We

are now in the early days of an extended period in which almost a century

of bogus prosperity founded on paper (not to mention, new and improved pure

zap electronic) money and debt which cannot ever be repaid will have to be

unwound. This will be painful in the extreme, and the profligate borrowers

who have been riding high whilst running up their credit cards will end up

marked down, not only in the economic realm but in geopolitical power.

Nobody imagines today that it would be possible, as Alan Greenspan envisioned

in the days he was a member of Ayn Rand's inner circle, to abolish the paper

money machine and return to honest money (or, even better, as Hayek recommended,

competing moneys, freely interchangeable in an open market). But then, nobody

imagines that the present system could collapse, which it is in the process of

doing. The US$ will continue its slide toward zero, perhaps with an inflection point

in the second derivative as the consequences of “bailouts” and

“stimuli” kick in. The Euro will first see

risk premiums

increase across sovereign debt issued by Eurozone nations, and then the

weaker members drop out to avoid the collapse of their own economies. No currency

union without political union has ever survived in the long term, and the Euro is

no exception.

Will we finally come to our senses and abandon this statist paper in favour of

the

mellow glow of gold?

This is devoutly to be wished, but I fear unlikely in my lifetime or even in

those of the koi in my pond. As long as politicians can fiddle with the money

in order to loot savers and investors to fund their patronage schemes and line

their own pockets they will: it's been going on since Babylon, and it will probably

go to the stars as we expand our dominion throughout the universe. One doesn't want

to hope for total economic and societal collapse, but that appears to be the best

bet for a return to honest and moral money. If that's your wish, I suppose you can

be heartened that the present administration in the United States appears bent upon

that outcome. Our other option is opting out with technology. We have the ability

today to electronically implement Hayek's multiple currency system online. This

has already been done by ventures such as e-gold, but The Man has, to date, effectively

stomped upon them. It will probably take a prickly sovereign state player to make

this work. Hello, Dubai!

Let me get back to this book. It is superb: read it and encourage all

of your similarly-inclined friends to do the same. If they're coming

in cold to these concepts, it may be a bit of a shock (“You

mean, the government doesn't create money?”), but

there's a bibliography at the end with three levels of reading lists

to bring people up to speed. Long-term supporters of hard money will

find this mostly a reinforcement of their views, but for those

experiencing for the first time the consequences of rapidly

depreciating dollars, this will be an eye-opening revelation of the

ultimate cause, and the malignant institution which must be abolished

to put an end to this most pernicious tax upon the most prudent of

citizens.

Now, would you be likely, were your own personal prosperity and that of all of

those around you on the line, to entrust your financial future to their

wisdom and demonstrated track record? Well, if you live in the United States, or

your finances are engaged in any way in that economy (whether as an investor,

creditor, or trade partner), you are, because this is the chart of

the purchasing power of the United States Dollar since it began to be managed

by the Federal Reserve System in 1913. Helluva record, don't you think?

Now, if you know anything about

basic economics

(which puts you several rungs up the ladder from most present-day

politicians and members of the chattering classes), you'll recall that

inflation is not defined as rising prices but rather an increase in the

supply of money. It's just as if you were at an auction and you gave all of

the bidders 10% more money: the selling price of the item would be 10%

greater, not because it had appreciated in value but simply because the

bidders had more to spend on acquiring it. And what is, fundamentally, the

function of the Federal Reserve System? Well, that would be to implement

an “elastic currency”, decoupled from real-world measures of

value, with the goal of smoothing out the business cycle. Looking at this

shorn of all the bafflegab, the mission statement is to create paper money

out of thin air in order to fund government programs which the legislature lacks

the spine to fund from taxation or debt, and to permit banks to profit by

extending credit well beyond the limits of prudence, knowing they're backed up

by the “lender of last resort” when things go South. The Federal

Reserve System is nothing other than an engine of inflation (money creation),

and it's hardly a surprise that the dollars it issues have lost more than 95%

of their value in the years since its foundation.

Acute observers of the economic scene have been warning about the

risks of such a system for decades—it came onto my personal

radar well before there was a human bootprint on the Moon. But somehow,

despite dollar crises, oil shocks, gold and silver bubble markets, saving and

loan collapse, dot.bomb, housing bubble, and all the rest, the wise money guys

somehow kept all of the balls in the air—until they didn't. We

are now in the early days of an extended period in which almost a century

of bogus prosperity founded on paper (not to mention, new and improved pure

zap electronic) money and debt which cannot ever be repaid will have to be

unwound. This will be painful in the extreme, and the profligate borrowers

who have been riding high whilst running up their credit cards will end up

marked down, not only in the economic realm but in geopolitical power.

Nobody imagines today that it would be possible, as Alan Greenspan envisioned

in the days he was a member of Ayn Rand's inner circle, to abolish the paper

money machine and return to honest money (or, even better, as Hayek recommended,

competing moneys, freely interchangeable in an open market). But then, nobody

imagines that the present system could collapse, which it is in the process of

doing. The US$ will continue its slide toward zero, perhaps with an inflection point

in the second derivative as the consequences of “bailouts” and

“stimuli” kick in. The Euro will first see

risk premiums

increase across sovereign debt issued by Eurozone nations, and then the

weaker members drop out to avoid the collapse of their own economies. No currency

union without political union has ever survived in the long term, and the Euro is

no exception.

Will we finally come to our senses and abandon this statist paper in favour of

the

mellow glow of gold?

This is devoutly to be wished, but I fear unlikely in my lifetime or even in

those of the koi in my pond. As long as politicians can fiddle with the money

in order to loot savers and investors to fund their patronage schemes and line

their own pockets they will: it's been going on since Babylon, and it will probably

go to the stars as we expand our dominion throughout the universe. One doesn't want

to hope for total economic and societal collapse, but that appears to be the best

bet for a return to honest and moral money. If that's your wish, I suppose you can

be heartened that the present administration in the United States appears bent upon

that outcome. Our other option is opting out with technology. We have the ability

today to electronically implement Hayek's multiple currency system online. This

has already been done by ventures such as e-gold, but The Man has, to date, effectively

stomped upon them. It will probably take a prickly sovereign state player to make

this work. Hello, Dubai!

Let me get back to this book. It is superb: read it and encourage all

of your similarly-inclined friends to do the same. If they're coming

in cold to these concepts, it may be a bit of a shock (“You

mean, the government doesn't create money?”), but

there's a bibliography at the end with three levels of reading lists

to bring people up to speed. Long-term supporters of hard money will

find this mostly a reinforcement of their views, but for those

experiencing for the first time the consequences of rapidly

depreciating dollars, this will be an eye-opening revelation of the

ultimate cause, and the malignant institution which must be abolished

to put an end to this most pernicious tax upon the most prudent of

citizens.

- Lyle, [Albert] Sparky and David Fisher.

The Year I Owned the Yankees.

New York: Bantam Books, [1990] 1991.

ISBN 978-0-553-28692-2.

-

“Sparky” Lyle

was one of the preeminent baseball relief pitchers of the 1970s. In 1977, he became

the first American League reliever to win the

Cy Young Award.

In this book, due to one of those bizarre tax-swap transactions

of the 1980–90s,

George Steinbrenner,

“The Boss”, was forced to divest the New York Yankees to

an unrelated owner. Well, who could be more unrelated than Sparky

Lyle, so when the telephone rings while he and his wife are

watching “Jeopardy”, the last thing he imagines is that

he's about to be offered a no-cash leveraged buy-out of the Yankees.

Based upon his extensive business experience, 238 career saves, and

pioneering in sitting naked on teammates' birthday cakes, he says,

“Why not?” and the game, and season, are afoot.

None of this ever happened: the subtitle is “A Baseball

Fantasy”, but wouldn't it have been delightful if it had?

There's the pitcher with a bionic arm, cellular phone gloves

so coaches can call fielders to position them for batters

(if they don't get the answering machine), the clubhouse at Yankee

Stadium enhanced with a Mood Room for those who wish to mellow

out and a Frustration Room for those inclined to smash and break

things after bruising losses, and the pitching coach who performs

an exorcism and conducts a seance manifesting the spirit of Cy Young

who counsels the Yankee pitching staff “Never hang a curve

to Babe Ruth”. Thank you, Cy! Then there's the Japanese

pitcher who can read minds and the reliever who reinvents himself

as “Mr. Cool” and rides in from the bullpen on a

Harley with the stadium PA system playing “Leader of the

Pack”.

This is a romp which, while the very quintessence of fantasy

baseball, also embodies a great deal of inside baseball wisdom.

It's also eerily prophetic, as

sabermetrics,

as practised by

Billy Beane's

Oakland A's years after this book was remaindered, plays a major

part in the plot. And never neglect the ultimate loyalty of a

fan to their team!

Sparky becomes the owner with a vow to be the anti-Boss, but discovers

as the season progresses that the realities of corporate baseball in

the 1990s mandate many of the policies which caused Steinbrenner

to be so detested. In the end, he comes to appreciate that any boss,

to do his or her job, must be, in part, The Boss. I wish I'd read that

before I discovered it for myself.

This is a great book to treat yourself to while the current World Series

involving the Yankees is contested. The book is out of print, but used

paperback copies in readable condition are abundant and reasonably

priced. Special thanks to the reader of this chronicle who

recommended

this book!