- Klemperer, Victor.

I Will Bear Witness. Vol. 2.

New York: Modern Library, [1942–1945, 1995, 1999] 2001.

ISBN 978-0-375-75697-9.

-

This is the second volume in Victor Klemperer's diaries

of life as a Jew in Nazi Germany.

Volume 1 (February 2009)

covers the years from 1933 through 1941, in which the

Nazis seized and consolidated their power, began to

increasingly persecute the Jewish population, and

rearm in preparation for their military conquests which

began with the invasion of Poland in September 1939.

I described that book as “simultaneously tedious,

depressing, and profoundly enlightening”. The author (a

cousin of the conductor Otto Klemperer) was a respected

professor of Romance languages and literature at the Technical

University of Dresden when Hitler came to power in 1933.

Although the son of a Reform rabbi, Klemperer had been baptised

in a Christian church and considered himself a protestant

Christian and entirely German. He volunteered for the German

army in World War I and served at the front in the artillery and

later, after recovering from a serious illness, in the army book

censorship office on the Eastern front. As a fully assimilated

German, he opposed all appeals to racial identity politics,

Zionist as well as Nazi.

Despite his conversion to protestantism, military service

to Germany, exalted rank as a professor, and decades of

marriage to a woman deemed “Aryan”

under the racial laws promulgated by the

Nazis, Klemperer was considered a “full-blooded

Jew” and was subject to ever-escalating harassment,

persecution, humiliation, and expropriation as the Nazis

tightened their grip on Germany. As civil society

spiralled toward barbarism, Klemperer lost his job, his car,

his telephone, his house, his freedom of movement, the

right to shop in “Aryan stores”, access to

public and lending libraries, and even the typewriter on

which he continued to write in the hope of maintaining his

sanity. His world shrank from that of a cosmopolitan

professor fluent in many European languages to a single

“Jews' house” in Dresden, shared with other

once-prosperous families similarly evicted from their homes.

As 1942 begins, it is apparent to many in German, even Jews

deprived of the “privilege” of reading newspapers

and listening to the radio, not to mention foreign broadcasts,

that the momentum of German conquest in the East had stalled and

that the Soviet winter counterattack had begun to push the

ill-equipped and -supplied German troops back from the lines

they held in the fall of 1941. This was reported with

euphemisms such as “shortening our line”, but it was

obvious to everybody that the Soviets, not long ago reported

breathlessly as “annihilated”, were nothing of the

sort and that the Nazi hope of a quick victory in the East, like

the fall of France in 1940, was not in the cards.

In Dresden, where Klemperer and his wife Eva remained

after being forced out of their house (to which, in

formalism-obsessed Germany, he retained title and

responsibility for maintenance), Jews were subjected

to a never-ending ratchet of abuse, oppression, and

terror. Klemperer was forced to wear the yellow star

(concealing it meant immediate arrest and likely

“deportation” to the concentration camps

in the East) and was randomly abused by strangers on

the street (but would get smiles and quiet words of

support from others), with each event shaking or

bolstering his confidence in those who, before Hitler,

he considered his “fellow Germans”.

He is prohibited from riding the tram, and must walk

long distances, avoiding crowded streets where the

risk of abuse from passers-by was greater. Another

blow falls when Jews are forbidden to use the public

library. With his typewriter seized long ago, he can

only pursue his profession with pen, ink, and whatever

books he can exchange with other Jews, including those

left behind by those “deported”. As

ban follows ban, even the simplest things such as getting

shoes repaired, obtaining coal to heat the house,

doing laundry, and securing food to eat become major

challenges. Jews are subject to random “house

searches” by the Gestapo, in which the discovery

of something like his diaries might mean immediate

arrest—he arranges to store the work with an

“Aryan” friend of Eva, who deposits pages

as they are completed. The house searches

in many cases amount to pure shakedowns, where

rationed and difficult-to-obtain goods such as

butter, sugar, coffee, and tobacco, even if purchased

with the proper coupons, are simply stolen by the

Gestapo goons.

By this time every Jew knows individuals and families who have

been “deported”, and the threat of joining them is

ever present. Nobody seems to know precisely what is going on

in those camps in the East (whose names are known: Auschwitz,

Dachau, Theresienstadt, etc.) but what is obvious is that nobody

sent there has ever been seen again. Sometimes relatives

receive a letter saying the deportee died of disease in the

camp, which seemed plausible, while others get notices their loved

one was “killed while trying to escape”, which was

beyond belief in the case of elderly prisoners who had

difficulty walking. In any case, being “sent East”

was considered equivalent to a death sentence which, for most,

it was. As a war veteran and married to an “Aryan”,

Klemperer was more protected than most Jews in Germany, but

there was always the risk that the slightest infraction might

condemn him to the camps. He knew many others who had been

deported shortly after the death of their Aryan wives.

As the war in the East grinds on, it becomes increasingly

clear that Germany is losing. The back-and-forth campaign

in North Africa was first to show cracks in the Nazi

aura of invincibility, but after the disaster at Stalingrad

in the winter of 1942–1943, it is obvious the situation

is dire. Goebbels proclaims “total war”, and

all Germans begin to feel the privation brought on by the

war. The topic on everybody's lips in whispered, covert

conversations is “How long can it go on?” With

each reverse there are hopes that perhaps a military coup

will depose the Nazis and seek peace with the Allies.

For Klemperer, such grand matters of state and history are

of relatively little concern. Much more urgent are obtaining

the necessities of life which, as the economy deteriorates

and oppression of the Jews increases, often amount to coal

to stay warm and potatoes to eat, hauled long distances

by manual labour. Klemperer, like all able-bodied Jews

(the definition of which is flexible: he suffers from heart

disease and often has difficulty walking long distances or

climbing stairs, and has vision problems as well) is assigned

“war work”, which in his case amounts to menial

labour tending machines producing stationery and envelopes

in a paper factory. Indeed, what appear in retrospect as

the pivotal moments of the war in Europe: the battles of

Stalingrad and Kursk, Axis defeat and evacuation of North

Africa, the fall of Mussolini and Italy's leaving the

Axis, the Allied D-day landings in Normandy, the assassination

plot against Hitler, and more almost seem to occur off-stage

here, with news filtering in bit by bit after the fact

and individuals trying to piece it together and make

sense of it all.

One event which is not off stage is the

bombing

of Dresden between February 13 and 15, 1945. The Klemperers

were living at the time in the Jews' house they shared with

several other families, which was located some distance from the

city centre. There was massive damage in the area, but it was

outside the firestorm which consumed the main targets. Victor

and Eva became separated in the chaos, but were reunited near

the end of the attack. Given the devastation and collapse of

infrastructure, Klemperer decided to bet his life on the hope

that the attack would have at least temporarily put the Gestapo

out of commission and removed the yellow star, discarded all

identity documents marking him as a Jew, and joined the mass of

refugees, many also without papers, fleeing the ruins of

Dresden. He and Eva made their way on what remained of the

transportation system toward Bavaria and eastern Germany, where

they had friends who might accommodate them, at least

temporarily. Despite some close calls, the ruse worked, and

they survived the end of the war, fall of the Nazi regime, and

arrival of United States occupation troops.

After a period in which he discovered that the American

occupiers, while meaning well, were completely overwhelmed

trying to meet the needs of the populace amid the ruins,

the Klemperers decided to make it on their own back to

Dresden, which was in the Soviet zone of occupation, where

they hoped their house still stood and would be restored

to them as their property. The book concludes with a

description of this journey across ruined Germany and

final arrival at the house they occupied before the Nazis

came to power.

After the war, Victor Klemperer was appointed a professor

at the University of Leipzig and resumed his academic

career. As political life resumed in what was then the

Soviet sector and later East Germany, he joined the

Socialist Unity Party of Germany, which is usually

translated to English as the East German Communist Party

and was under the thumb of Moscow. Subsequently, he became

a cultural ambassador of sorts for East Germany. He seems

to have been a loyal communist, although in his later

diaries he expressed frustration at the impotence of the

“parliament” in which he was a delegate

for eight years. Not to be unkind to somebody who survived

as much oppression and adversity as he did, but he didn't

seem to have much of a problem with a totalitarian, one party,

militaristic, intrusive surveillance, police state as long

as it wasn't directly persecuting him.

The author was a prolific diarist who wrote thousands of

pages from the early 1900s throughout his

long life. The original 1995 German publication of the

1933–1945 diaries as

Ich will Zeugnis

ablegen bis zum letzten

was a substantial abridgement of the original document

and even so ran to almost 1700 pages. This English

translation further abridges the diaries and still

often seems repetitive. End notes provide historical

context, identify the many people who figure in the diary,

and translate the foreign phrases the author liberally

sprinkles among the text.

- Anonymous Conservative [Michael Trust].

The Evolutionary Psychology Behind Politics.

Macclenny, FL: Federalist Publications, [2012, 2014] 2017.

ISBN 978-0-9829479-3-7.

-

One of the puzzles noted by observers of the contemporary

political and cultural scene is the division of the population

into two factions, (called in the sloppy terminology of the

United States) “liberal” and “conservative”,

and that if you pick a member from either faction by

observing his or her position on one of the divisive issues

of the time, you can, with a high probability of accuracy,

predict their preferences on all of a long list of other issues

which do not, on the face of it, seem to have very much to do

with one another. For example, here is a list of present-day

hot-button issues, presented in no particular order.

- Health care, socialised medicine

- Climate change, renewable energy

- School choice

- Gun control

- Higher education subsidies, debt relief

- Free speech (hate speech laws, Internet censorship)

- Deficit spending, debt, and entitlement reform

- Immigration

- Tax policy, redistribution

- Abortion

- Foreign interventions, military spending

What a motley collection of topics! About the only thing they

have in common is that the omnipresent administrative

super-state has become involved in them in one way or another,

and therefore partisans of policies affecting them view it

important to influence the state's action in their regard. And

yet, pick any one, tell me what policies you favour, and I'll

bet I can guess at where you come down on at least eight of the

other ten. What's going on?

Might there be some deeper, common thread or cause which

explains this otherwise curious clustering of opinions? Maybe

there's something rooted in biology, possibly even heritable,

which predisposes people to choose the same option on disparate

questions? Let's take a brief excursion into ecological

modelling and see if there's something of interest there.

As with all modelling, we start with a simplified, almost

cartoon abstraction of the gnarly complexity of the real world.

Consider a closed territory (say, an island) with abundant

edible vegetation and no animals. Now introduce a species, such

as rabbits, which can eat the vegetation and turn it into more

rabbits. We start with a small number, P, of rabbits.

Now, once they get busy with bunny business, the population will

expand at a rate r which is essentially constant over a

large population. If r is larger than 1 (which for

rabbits it will be, with litter sizes between 4 and 10 depending on

the breed, and gestation time around a month) the population

will increase. Since the rate of increase is constant and the

total increase is proportional to the size of the existing

population, this growth will be exponential. Ask any

Australian.

Now, what will eventually happen? Will the island disappear under

a towering pile of rabbits inexorably climbing to the top of

the atmosphere? No—eventually the number of rabbits will

increase to the point where they are eating all the

vegetation the territory can produce. This number, K,

is called the “carrying capacity” of the environment,

and it is an absolute number for a given species and environment. This

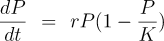

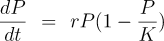

can be expressed as a differential equation called the

Verhulst

model, as follows:

It's a maxim among popular science writers that every equation

you include cuts your readership by a factor of two, so among

the hardy half who remain, let's see how this works. It's really

very simple (and indeed, far simpler than actual population

dynamics in a real environment). The left side,

“dP/dt” simply means “the rate of growth

of the population P with respect to time, t”.

On the right hand side, “rP” accounts for the

increase (or decrease, if r is less than 0) in population,

proportional to the current population. The population is limited

by the carrying capacity of the habitat, K, which is

modelled by the factor “(1 − P/K)”.

Now think about how this works: when the population is very small,

P/K will be close to zero and, subtracted from one,

will yield a number very close to one. This, then, multiplied by

the increase due to rP will have little effect and the

growth will be largely unconstrained. As the population P

grows and begins to approach K, however, P/K

will approach unity and the factor will fall to zero, meaning that

growth has completely stopped due to the population reaching

the carrying capacity of the environment—it simply doesn't

produce enough vegetation to feed any more rabbits. If the rabbit

population overshoots, this factor will go negative and there will

be a die-off which eventually brings the population P

below the carrying capacity K. (Sorry if this seems

tedious; one of the great things about learning even a very little

about differential equations is that all of this is apparent at a

glance from the equation once you get over the speed bump of

understanding the notation and algebra involved.)

This is grossly over-simplified. In fact, real populations are

prone to oscillations and even chaotic dynamics, but we don't

need to get into any of that for what follows, so I won't.

Let's complicate things in our bunny paradise by introducing a

population of wolves. The wolves can't eat the vegetation, since

their digestive systems cannot extract nutrients from it, so

their only source of food is the rabbits. Each wolf eats many

rabbits every year, so a large rabbit population is required to

support a modest number of wolves. Now if we go back and look

at the equation for wolves, K represents the number of

wolves the rabbit population can sustain, in the steady state,

where the number of rabbits eaten by the wolves just balances

the rabbits' rate of reproduction. This will often result in

a rabbit population smaller than the carrying capacity

of the environment, since their population is now constrained

by wolf predation and not K.

What happens as this (oversimplified) system cranks away,

generation after generation, and Darwinian evolution kicks in?

Evolution consists of two processes: variation, which is largely

random, and selection, which is sensitively dependent upon the

environment. The rabbits are unconstrained by K, the

carrying capacity of their environment. If their numbers

increase beyond a population P substantially smaller

than K, the wolves will simply eat more of them and

bring the population back down. The rabbit population, then, is

not at all constrained by K, but rather by r:

the rate at which they can produce new offspring. Population

biologists call this an r-selected species: evolution

will select for individuals who produce the largest number of

progeny in the shortest time, and hence for a life cycle which

minimises parental investment in offspring and against mating

strategies, such as lifetime pair bonding, which would limit

their numbers. Rabbits which produce fewer offspring will lose

a larger fraction of them to predation (which affects all

rabbits, essentially at random), and the genes which they carry

will be selected out of the population. An r-selected

population, sometimes referred to as

r-strategists, will tend to be small, with short

gestation time, high fertility (offspring per litter), rapid

maturation to the point where offspring can reproduce, and broad

distribution of offspring within the environment.

Wolves operate under an entirely different set of constraints.

Their entire food supply is the rabbits, and since it takes a

lot of rabbits to keep a wolf going, there will be fewer wolves

than rabbits. What this means, going back to the Verhulst

equation, is that the 1 − P/K

factor will largely determine their population: the carrying

capacity K of the environment supports a much smaller

population of wolves than their food source, rabbits, and if

their rate of population growth r were to increase, it

would simply mean that more wolves would starve due to

insufficient prey. This results in an entirely different set of

selection criteria driving their evolution: the wolves are said

to be K-selected or K-strategists. A

successful wolf (defined by evolution theory as more likely to

pass its genes on to successive generations) is not one which

can produce more offspring (who would merely starve by hitting

the K limit before reproducing), but rather highly

optimised predators, able to efficiently exploit the limited

supply of rabbits, and to pass their genes on to a small number

of offspring, produced infrequently, which require substantial

investment by their parents to train them to hunt and,

in many cases, acquire social skills to act as part of a group

that hunts together. These K-selected species tend to

be larger, live longer, have fewer offspring, and have parents

who spend much more effort raising them and training them to be

successful predators, either individually or as part of a pack.

“K or r, r or K:

once you've seen it, you can't look away.”

Just as our island of bunnies and wolves was over-simplified,

the dichotomy of r- and K-selection is rarely

precisely observed in nature (although rabbits and wolves are

pretty close to the extremes, which it why I chose them). Many

species fall somewhere in the middle and, more importantly,

are able to shift their strategy on the fly, much faster than

evolution by natural selection, based upon the availability of

resources. These r/K shape-shifters react to

their environment. When resources are abundant, they adopt an

r-strategy, but as their numbers approach the carrying

capacity of their environment, shift to life cycles

you'd expect from K-selection.

What about humans? At a first glance, humans would seem to be

a quintessentially K-selected species. We are

large, have long lifespans (about twice as long as we

“should” based upon the number of heartbeats per

lifetime of other mammals), usually only produce one child (and

occasionally two) per gestation, with around a one year turn-around

between children, and massive investment by parents in

raising infants to the point of minimal autonomy and many

additional years before they become fully functional adults. Humans

are “knowledge workers”, and whether they are

hunter-gatherers, farmers, or denizens of cubicles at The

Company, live largely by their wits, which are a combination

of the innate capability of their hypertrophied brains and

what they've learned in their long apprenticeship through

childhood. Humans are not just predators on what they

eat, but also on one another. They fight, and they fight in

bands, which means that they either develop the social

skills to defend themselves and meet their needs by raiding

other, less competent groups, or get selected out in the

fullness of evolutionary time.

But humans are also highly adaptable. Since modern humans

appeared some time between fifty and two hundred thousand years

ago they have survived, prospered, proliferated, and spread

into almost every habitable region of the Earth. They have

been hunter-gatherers, farmers, warriors, city-builders,

conquerors, explorers, colonisers, traders, inventors,

industrialists, financiers, managers, and, in the

Final Days

of their species, WordPress site administrators.

In many species, the selection of a predominantly r

or K strategy is a mix of genetics and switches

that get set based upon experience in the environment. It is

reasonable to expect that humans, with their large brains and

ability to override inherited instinct, would be

especially sensitive to signals directing them to one or

the other strategy.

Now, finally, we get back to politics. This was a post about

politics. I hope you've been thinking about it as we spent

time in the island of bunnies and wolves, the cruel realities

of natural selection, and the arcana of differential equations.

What does r-selection produce in a human

population? Well, it might, say, be averse to competition

and all means of selection by measures of performance. It would

favour the production of large numbers of offspring at an

early age, by early onset of mating, promiscuity, and

the raising of children by single mothers with minimal

investment by them and little or none by the fathers (leaving

the raising of children to the State). It would welcome

other r-selected people into the community, and

hence favour immigration from heavily r populations.

It would oppose any kind of selection based upon performance,

whether by intelligence tests, academic records, physical

fitness, or job performance. It would strive to create the

ideal r environment of unlimited resources,

where all were provided all their basic needs without having

to do anything but consume. It would oppose and be repelled

by the K component of the population, seeking to

marginalise it as toxic, privileged, or

exploiters of the real people. It might

even welcome conflict with K warriors of adversaries

to reduce their numbers in otherwise pointless foreign adventures.

And K-troop? Once a society in which they initially

predominated creates sufficient wealth to support a burgeoning

r population, they will find themselves outnumbered and

outvoted, especially once the r wave removes the

firebreaks put in place when K was king to guard

against majoritarian rule by an urban underclass. The

K population will continue to do what they do best:

preserving the institutions and infrastructure which sustain

life, defending the society in the military, building and

running businesses, creating the basic science and technologies

to cope with emerging problems and expand the human potential,

and governing an increasingly complex society made up, with

every generation, of a population, and voters, who are

fundamentally unlike them.

Note that the r/K model completely explains

the “crunchy to soggy” evolution of societies

which has been remarked upon since antiquity. Human

societies always start out, as our genetic heritage predisposes

us to, K-selected. We work to better our condition

and turn our large brains to problem-solving and, before

long, the privation our ancestors endured turns into

a pretty good life and then, eventually, abundance. But

abundance is what selects for the r strategy. Those

who would not have reproduced, or have as many children in

the K days of yore, now have babies-a-poppin' as in

the introduction to

Idiocracy,

and before long, not waiting for genetics to do its inexorable

work, but purely by a shift in incentives, the rs outvote

the Ks and the Ks begin to count the days until

their society runs out of the wealth which can be plundered

from them.

But recall that equation. In our simple bunnies and wolves

model, the resources of the island were static. Nothing the

wolves could do would increase K and permit a larger

rabbit and wolf population. This isn't the case for humans.

K humans dramatically increase the carrying capacity of

their environment by inventing new technologies such as

agriculture, selective breeding of plants and animals,

discovering and exploiting new energy sources such as firewood,

coal, and petroleum, and exploring and settling new territories

and environments which may require their discoveries to render

habitable. The rs don't do these things. And as the

rs predominate and take control, this momentum stalls

and begins to recede. Then the hard times ensue. As

Heinlein said many years ago, “This

is known as bad luck.”

And then the

Gods

of the Copybook Headings will, with terror and slaughter return.

And K-selection will, with them, again assert itself.

Is this a complete model, a Rosetta stone for human behaviour? I

think not: there are a number of things it doesn't explain, and

the shifts in behaviour based upon incentives are much too fast

to account for by genetics. Still, when you look at those eleven

issues I listed so many words ago through the r/K

perspective, you can almost immediately see how each strategy maps

onto one side or the other of each one, and they are consistent with

the policy preferences of “liberals” and

“conservatives”. There is also some rather fuzzy

evidence for genetic differences (in particular the

DRD4-7R

allele of the dopamine receptor and size of the right brain

amygdala) which

appear to correlate with ideology.

Still, if you're on one side of the ideological divide and

confronted with somebody on the other and try to argue

from facts and logical inference, you may end up throwing up

your hands (if not your breakfast) and saying, “They

just don't get it!” Perhaps they don't.

Perhaps they can't. Perhaps there's a difference

between you and them as great as that between rabbits and

wolves, which can't be worked out by predator and prey sitting

down and voting on what to have for dinner. This may not be

a hopeful view of the political prospect in the near future,

but hope is not a strategy and to survive and prosper requires

accepting reality as it is and acting accordingly.

- Carroll, Michael.

Europa's Lost Expedition.

Cham, Switzerland: Springer International, 2017.

ISBN 978-3-319-43158-1.

-

In the epoch in which this story is set the expansion of the

human presence into the solar system was well advanced, with

large settlements on the Moon and Mars, exploitation of the

abundant resources in the main asteroid belt, and research

outposts in exotic environments such as Jupiter's enigmatic moon

Europa, when civilisation on Earth was consumed, as so often

seems to happen when too many primates who evolved to live in

small bands are packed into a limited space, by a

global conflict which the survivors, a decade later, refer to

simply as “The War”, as its horrors and costs

dwarfed all previous human conflicts.

Now, with The War over and recovery underway, scientific work is

resuming, and an international expedition has been launched to

explore the southern hemisphere of Europa, where the icy crust

of the moon is sufficiently thin to provide access to the liquid

water ocean beneath and the complex orbital dynamics of

Jupiter's moons were expected to trigger a once in a decade

eruption of geysers, with cracks in the ice allowing the ocean

to spew into space, providing an opportunity to sample it

“for free”.

Europa is not a hospitable environment for humans. Orbiting

deep within Jupiter's magnetosphere, it is in the heart of the

giant planet's radiation belts, which are sufficiently powerful

to kill an unprotected human within minutes. But the radiation

is not uniform and humans are clever. The main base on Europa,

Taliesen, is located on the face of the moon that points away

from Jupiter, and in the leading hemisphere where radiation is

least intense. On Europa, abundant electrical power is

available simply by laying out cables along the surface, in

which Jupiter's magnetic field induces powerful currents as they

cut it. This power is used to erect a magnetic shield around

the base which protects it from the worst, just as Earth's

magnetic field shields life on its surface. Brief ventures into

the “hot zone” are made possible by shielded rovers

and advanced anti-radiation suits.

The present expedition will not be the first to attempt exploration

of the southern hemisphere. Before the War, an expedition with

similar objectives ended in disaster, with the loss of all members

under circumstances which remain deeply mysterious, and of which

the remaining records, incomplete and garbled by radiation,

provide few clues as to what happened to them. Hadley Nobile,

expedition leader, is not so much concerned with the past

as making the most of this rare opportunity. Her deputy

and long-term collaborator, Gibson van Clive, however, is fascinated

by the mystery and spends hours trying to recover and piece

together the fragmentary records from the lost expedition and

research the backgrounds of its members and the physical

evidence, some of which makes no sense at all. The other

members of the new expedition are known from their scientific

reputations, but not personally to the leaders. Many people

have blanks in their curricula vitae during the

War years, and those who lived through that time are rarely

inclined to probe too deeply.

Once the party arrive at Taliesen and begin preparations for

their trip to the south, a series of “accidents”

befall some members, who are found dead in circumstances which

seem implausible based upon their experience. Down to the bare

minimum team, with a volunteer replacement from the base's

complement, Hadley decides to press on—the geysers wait

for no one.

Thus begins what is basically a murder mystery, explicitly

patterned on Agatha Christie's And Then

There Were None, layered upon the enigmas of the lost

expedition, the backgrounds of those in the current team, and

the biosphere which may thrive in the ocean beneath the ice,

driven by the tides raised by Jupiter and the other moons and

fed by undersea plumes similar to those where some suspect life

began on Earth.

As a mystery, there is little more that can be said without

crossing the line into plot spoilers, so I will refrain from

further description. Worthy of a Christie tale, there are many

twists and turns, and few things are as the seem on the

surface.

As in his previous novel, On the Shores of

Titan's Farthest Sea (December 2016), the author, a

distinguished scientific illustrator and popular science writer,

goes to great lengths to base the exotic locale in which the

story is set upon the best presently-available scientific

knowledge. An appendix, “The Science Behind the

Story”, provides details and source citations for the

setting of the story and the technologies which figure in it.

While the science and technology are plausible extrapolations

from what is presently known, the characters sometimes seem to

behave more in the interests of advancing the plot than as real

people would in such circumstances. If you were the leader or

part of an expedition several members of which had died under

suspicious circumstances at the base camp, would you really be

inclined to depart for a remote field site with spotty

communications along with all of the prime suspects?

- Dutton, Edward.

How to Judge People by What they Look Like.

Oulu, Finland: Thomas Edward Press, 2018.

ISBN 978-1-9770-6797-5.

-

In The Picture of Dorian Gray,

Oscar Wilde wrote,

People say sometimes that Beauty is only superficial.

That may be so. But at least it is not as superficial

as Thought. To me, Beauty is the wonder of wonders.

It is only shallow people who do not judge by

appearances.

From childhood, however, we have been exhorted not to judge

people by their appearances. In

Skin in the Game (August 2019),

Nassim Nicholas Taleb advises choosing the surgeon who

“doesn't

look like a surgeon” because their success is more likely

due to competence than first impressions.

Despite this,

physiognomy,

assessing a person's characteristics from their appearance, is

as natural to humans as breathing, and has been an instinctual

part of human behaviour as old as our species. Thinkers and writers

from Aristotle through the great novelists of the 19th century

believed that an individual's character was reflected in, and

could be inferred from their appearance, and crafted and

described their characters accordingly. Jules Verne would

often spend a paragraph describing the appearance of his

characters and what that implied for their behaviour.

Is physiognomy all nonsense, a pseudoscience like

phrenology,

which purported to predict mental characteristics by measuring

bumps on the skull which were claimed indicate the development

of “cerebral organs” with specific functions? Or,

is there something to it, after all? Humans are a social

species and, as such, have evolved to be exquisitely sensitive

to signals sent by others of their kind, conveyed through subtle

means such as a tone of voice, facial expression, or posture.

Might we also be able to perceive and interpret messages which

indicate properties such as honesty, intelligence, courage,

impulsiveness, criminality, diligence, and more? Such an

ability, if possible, would be advantageous to individuals in

interacting with others and, contributing to success in

reproducing and raising offspring, would be selected for by

evolution.

In this short book (or long essay—the text is just 85

pages), the author examines the evidence and concludes that

there are legitimate correlations between appearance and

behaviour, and that human instincts are picking up genuine

signals which are useful in interacting with others. This

seems perfectly plausible: the development of the human body

and face are controlled by the genetic inheritance of the

individual and modulated through the effects of hormones, and

it is well-established that both genetics and hormones are

correlated with a variety of behavioural traits.

Let's consider a reasonably straightforward example. A

study published in 2008 found a statistically significant

correlation between the width of the face (cheekbone to

cheekbone distance compared to brow to upper lip) and

aggressiveness (measured by the number of penalty

minutes received) among a sample of 90 ice hockey

players. Now, a wide face is also known to correlate

with a high testosterone level in males, and testosterone

correlates with aggressiveness and selfishness. So, it

shouldn't be surprising to find the wide face morphology

correlated with the consequences of high-testosterone

behaviour.

In fact, testosterone and other hormone levels play a

substantial part in many of the correlations between appearance

and behaviour discussed by the author. Many people believe

they can identify, with reasonable reliability, homosexuals

just from their appearance: the term “gaydar”

has come into use for this ability. In 2017, researchers

trained an artificial intelligence program with a set of

photographs of individuals with known sexual orientations

and then tested the program on a set of more than 35,000

images. The program correctly identified the sexual

orientation of men 81% of the time and women with 74%

accuracy.

Of course, appearance goes well beyond factors which are inherited

or determined by hormones. Tattoos, body piercings, and other

irreversible modifications of appearance correlate with low

time preference, which correlates with low intelligence and

the other characteristics of r-selected

lifestyle. Choices of clothing indicate an individual's

self-identification, although fashion trends change rapidly

and differ from region to region, so misinterpretation is a

risk.

The author surveys a wide variety of characteristics including

fat/thin body type, musculature, skin and hair, height,

face shape, breast size in women, baldness and beards in men,

eye spacing, tattoos, hair colour, facial symmetry,

handedness, and finger length ratio, and presents

citations to research, most published recently, supporting

correlations between these aspects of appearance and

behaviour. He cautions that while people may be good at

sensing and interpreting these subtle signals among members

of their own race, there are substantial and consistent

differences between the races, and no inferences can be

drawn from them, nor are members of one race generally

able to read the signals from members of another.

One gets the sense (although less strongly) that this is another

field where advances in genetics and data science are piling

up a mass of evidence which will roll over the stubborn defenders

of the “blank slate” like a truth tsunami. And

again, this is an area where people's instincts, honed by

millennia of evolution, are still relied upon despite the

scorn of “experts”. (So afraid were the authors

of the Wikipedia

page

on physiognomy [retrieved 2019-12-16] of the “computer

gaydar” paper mentioned above that they declined to cite

the

peer reviewed paper in the

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology but

instead linked to a BBC News piece which dismissed

it as “dangerous” and “junk science”.

Go on whistling, folks, as the wave draws near and begins to crest….)

Is the case for physiognomy definitively made? I think not, and

as I suspect the author would agree, there are many aspects of

appearance and a multitude of personality traits, some of which

may be significantly correlated and others not at all. Still,

there is evidence for some linkage, and it appears to be growing

as more work in the area (which is perilous to the careers of

those who dare investigate it) accumulates. The scientific

evidence, summarised here, seems to be, as so often happens,

confirming the instincts honed over hundreds of generations by

the inexorable process of evolution: you can form some

conclusions just by observing people, and this information is

useful in the competition which is life on Earth. Meanwhile,

when choosing programmers for a project team, the one who shows up

whose eyebrows almost meet their hairline, sporting a plastic baseball

cap worn backward with the adjustment strap on the smallest peg,

with a scraggly soybeard, pierced nose, and visible tattoos isn't

likely to be my pick. She's probably a WordPress developer.

- Walton, David.

Three Laws Lethal.

Jersey City, NJ: Pyr, 2019.

ISBN 978-1-63388-560-8.

-

In the near future, autonomous vehicles, “autocars”,

are available from a number of major automobile manufacturers.

The self-driving capability, while not infallible, has been

approved by regulatory authorities after having demonstrated

that it is, on average, safer than the population of human

drivers on the road and not subject to human frailties such as

driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs, while tired, or

distracted by others in the car or electronic gadgets. While

self-driving remains a luxury feature with which a minority of

cars on the road are equipped, regulators are confident that as

it spreads more widely and improves over time, the highway

accident rate will decline.

But placing an algorithm and sensors in command of a vehicle

with a mass of more than a tonne hurtling down the road at 100

km per hour or faster is not just a formidable technical

problem, it is one with serious and unavoidable moral

implications. These come into stark focus when, in an incident

on a highway near Seattle, an autocar swerves to avoid a tree

crashing down on the highway, hitting and killing a motorcyclist

in an adjacent lane of which the car's sensors must have been

aware. The car appears to have made a choice, valuing

the lives of its passengers: a mother and her two children, over

that of the motorcyclist. What really happened, and how the car

decided what to do in that split-second, is opaque, because the

software controlling it was, as all such software, proprietary

and closed to independent inspection and audit by third

parties. It's one thing to acknowledge that self-driving

vehicles are safer, as a whole, than those with humans behind

the wheel, but entirely another to cede to them the moral agency

of life and death on the highway. Should an autocar value the

lives of its passengers over those of others? What if there

were a sole passenger in the car and two on the motorcycle? And

who is liable for the death of the motorcyclist: the auto

manufacturer, the developers of the software, the owner of car,

the driver who switched it into automatic mode, or the

regulators who approved its use on public roads? The case was

headed for court, and all would be watching the precedents it

might establish.

Tyler Daniels and Brandon Kincannon, graduate students in the

computer science department of the University of Pennsylvania,

were convinced they could do better. The key was going beyond

individual vehicles which tried to operate autonomously based

upon what their own sensors could glean from their immediate

environment, toward an architecture where vehicles communicated

with one another and coordinated their activities. This would

allow sharing information over a wider area and be able to avoid

accidents resulting from individual vehicles acting without the

knowledge of the actions of others. Further, they wanted to

re-architect individual ground transportation from a model of

individually-owned and operated vehicles to transportation as a

service, where customers would summon an autocar on demand with

their smartphone, with the vehicle network dispatching the

closest free car to their location. This would dramatically

change the economics of personal transportation. The typical private

car spends twenty-two out of twenty-four hours parked, taking up

a parking space and depreciating as it sits idle. The

transportation service autocar would be in constant service

(except for downtime for maintenance, refuelling, and times of

reduced demand), generating revenue for its operator. An angel

investor believes their story and, most importantly, believes in

them sufficiently to write a check for the initial demonstration

phase of their project, and they set to work.

Their team consists of Tyler and Brandon, plus Abby and Naomi

Sumner, sisters who differed in almost every way: Abby outgoing

and vivacious, with an instinct for public relations and

marketing, and Naomi the super-nerd, verging on being “on

the spectrum”. The big day of the public roll-out of the

technology arrives, and ends in disaster, killing Abby in what

was supposed to be a demonstration of the system's inherent

safety. The disaster puts an end to the venture and the

surviving principals go their separate ways. Tyler signs on as

a consultant and expert witness for the lawyers bringing the

suit on behalf of the motorcyclist killed in Seattle, using the

exposure to advocate for open source software being a

requirement for autonomous vehicles. Brandon uses money

inherited after the death of his father to launch a new venture,

Black Knight, offering transportation as a service initially in

the New York area and then expanding to other cities. Naomi,

whose university experiment in genetic software implemented as

non-player characters (NPCs) in a virtual world was the

foundation of the original venture's software, sees Black Knight

as a way to preserve the world and beings she has created as

they develop and require more and more computing resources.

Characters in the virtual world support themselves and compete

by driving Black Knight cars in the real world, and as

generation follows generation and natural selection works its

wonders, customers and competitors are amazed at how Black

Knight vehicles anticipate the needs of their users and maintain

an unequalled level of efficiency.

Tyler leverages his recognition from the trial into a new

self-driving venture based on open source software called

“Zoom”, which spreads across the U.S. west coast and

eventually comes into competition with Black Knight in the

east. Somehow, Zoom's algorithms, despite being open and having

a large community contributing to their development, never seem

able to equal the service provided by Black Knight, which is so

secretive that even Brandon, the CEO, doesn't know how Naomi's

software does it.

In approaching any kind of optimisation problem such as

scheduling a fleet of vehicles to anticipate and respond to

real-time demand, a key question is choosing the

“objective function”: how the performance of the

system is evaluated based upon the stated goals of its

designers. This is especially crucial when the optimisation is

applied to a system connected to the real world. The parable of

the

“Clippy

Apocalypse”, where an artificial intelligence put in

charge of a paperclip factory and trained to maximise the

production of paperclips escapes into the wild and eventually

converts first its home planet, then the rest of the solar

system, and eventually the entire visible universe into paper

clips. The system worked as designed—but the objective

function was poorly chosen.

Naomi's NPCs literally (or virtually) lived or died based upon

their ability to provide transportation service to Black

Knight's customers, and natural selection, running at the

accelerated pace of the simulation they inhabited, relentlessly

selected them with the objective of improving their service and

expanding Black Knight's market. To the extent that, within

their simulation, they perceived opposition to these goals, they

would act to circumvent it—whatever it takes.

This sets the stage for one of the more imaginative tales of how

artificial general intelligence might arrive through the back

door: not designed in a laboratory but emerging through the

process of evolution in a complex system subjected to real-world

constraints and able to operate in the real world. The moral

dimensions of this go well beyond the trolley

problem often cited in connection with autonomous vehicles,

dealing with questions of whether artificial intelligences we

create for our own purposes are tools, servants, or slaves, and

what happens when their purposes diverge from those for which we

created them.

This is a techno-thriller, with plenty of action in the

conclusion of the story, but also a cerebral exploration of the

moral questions which something as seemingly straightforward and

beneficial as autonomous vehicles may pose in the future.

- Taloni, John.

The Compleat Martian Invasion.

Seattle: Amazon Digital Services, 2016.

ASIN B01HLTZ7MS.

-

A number of years have elapsed since the Martian Invasion

chronicled by H.G. Wells in

The War of

the Worlds. The damage inflicted on the Earth was

severe, and the protracted process of recovery, begun in the

British Empire in the last years of Queen Victoria's reign, now

continues under Queen Louise, Victoria's sixth child and eldest

surviving heir after the catastrophe of the invasion. Just as

Earth is beginning to return to normalcy, another crisis has

emerged. John Bedford, who had retreated into an opium haze

after the horrors of his last expedition, is summoned to Windsor

Castle where Queen Louise shows him a photograph. “Those

are puffs of gas on the Martian surface. The Martians are

coming again, Mr. Bedford. And in far greater numbers.”

Defeated the last time only due to their vulnerability to

Earth's microbes, there is every reason to expect that this time

the Martians will have taken precautions against that threat to

their plans for conquest.

Earth's only hope to thwart the invasion before it reaches the

surface and unleashes further devastation on its inhabitants is

deploying weapons on platforms employing the anti-gravity

material Cavorite, but the secret of manufacturing it rests with

its creator, Cavor, who has been taken prisoner by the ant-like

Selenites in the expedition from which Mr Bedford narrowly

escaped, as chronicled in Mr Wells's

The

First Men in the Moon. Now, Bedford must embark on a perilous

attempt to recover the Cavorite sphere lost at the end of his

last adventure and then join an expedition to the Moon to rescue

Cavor from the caves of the Selenites.

Meanwhile, on Barsoom (Mars),

John Carter

and Deja Thoris find

their beloved city of Helium threatened by the Khondanes, whose

deadly tripods wreaked so much havoc on Earth not long ago and

are now turning their envious eyes back to the plunder that

eluded them on the last attempt.

Queen Louise must assemble an international alliance, calling on

all of her crowned relatives: Czar Nicholas, Kaiser Wilhelm, and

even those troublesome republican Americans, plus all the

resources they can summon—the inventions of the Serbian,

Tesla, the research of Maria Skłowdowska and her young

Swiss assistant Albert, discovered toiling away in the patent

office, the secrets recovered from Captain Nemo's island, and

the mysterious interventions of the

Time

Traveller, who flickers in and out of existence at various

moments, pursuing his own inscrutable agenda. As the conflict

approaches and battle is joined, an interplanetary effort is

required to save Earth from calamity.

As you might expect from this description, this is a

rollicking good romp replete with references and tips of

the hat to the classics of science fiction and their

characters. What seems like a straightforward tale of

battle and heroism takes a turn at the very end into

the inspiring, with a glimpse of how different human

history might have been.

At present, only a Kindle edition is

available, which is free for Kindle Unlimited subscribers.

- Page, Joseph T., II.

Vandenberg Air Force Base.

Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2014.

ISBN 978-1-4671-3209-1.

-

Prior to World War II, the sleepy rural part of the

southern California coast between Santa Barbara

and San Luis Obispo was best known as the location

where, in September 1923, despite a lighthouse having

been in operation at Arguello Point since 1901, the

U.S. Navy suffered its worst peacetime disaster, when

seven destroyers, travelling at 20 knots,

ran

aground at Honda Point, resulting in the loss of

all seven ships and the deaths of 23 crewmembers. In the

1930s, following additional wrecks in the area, a

lifeboat station was established in conjunction

with the lighthouse.

During World War II, the Army acquired 92,000 acres

(372 km²) in the area for a training base which

was called Camp Cooke, after a cavalry general who

served in the Civil War, in wars with Indian tribes, and

in the Mexican-American War. The camp was used for

training Army troops in a variety of weapons and in

tank maneuvers. After the end of the war, the base was

closed and placed on inactive status, but was re-opened

after the outbreak of war in Korea to train tank crews.

It was once again mothballed in 1953, and remained

inactive until 1957, when 64,000 acres were transferred

to the U.S. Air Force to establish a missile base on

the West Coast, initially called Cooke Air Force Base,

intended to train missile crews and also serve as the

U.S.'s first operational intercontinental ballistic

missile (ICBM) site. On October 4th, 1958, the base was

renamed Vandenberg Air Force Base in honour of the late

General Hoyt

Vandenberg, former Air Force Chief of Staff and

Director of Central Intelligence.

On December 15, 1958, a Thor intermediate range ballistic

missile was launched from the new base, the first of hundreds of

launches which would follow and continue up to the present day.

Starting in September 1959, three Atlas ICBMs armed with nuclear

warheads were deployed on open launch pads at Vandenberg, the

first U.S. intercontinental ballistic missiles to go on alert.

The Atlas missiles remained part of the U.S. nuclear force until

their retirement in May 1964.

With the advent of Earth satellites, Vandenberg became a key

part of the U.S. military and civil space infrastructure.

Launches from Cape Canaveral in Florida are restricted to a

corridor directed eastward over the Atlantic ocean. While this

is fine for satellites bound for equatorial orbits, such as the

geostationary orbits used by many communication satellites, a

launch into polar orbit, preferred by military reconnaissance

satellites and Earth resources satellites because it allows them

to overfly and image locations anywhere on Earth, would result

in the rockets used to launch them dropping spent stages on

land, which would vex taxpayers to the north and hotheated Latin

neighbours to the south.

Vandenberg Air Force Base, however, situated on a point

extending from the California coast, had nothing to the

south but open ocean all the way to Antarctica. Launching

southward, satellites could be placed into polar or

Sun

synchronous orbits without disturbing anybody but the

fishes. Vandenberg thus became the prime launch site

for U.S. reconnaissance satellites which, in the early

days when satellites were short-lived and returned film

to the Earth, required a large number of launches. The

Corona

spy satellites alone accounted for

144 launches from Vandenberg between 1959 and 1972.

With plans in the 1970s to replace all U.S. expendable launchers

with the Space Shuttle, facilities were built at Vandenberg

(Space

Launch Complex 6) to process and launch the Shuttle, using a

very different architecture than was employed in Florida. The

Shuttle stack would be assembled on the launch pad, protected by

a movable building that would retract prior to launch. The

launch control centre was located just 365 metres from the

launch pad (as opposed to 4.8 km away at the Kennedy Space

Center in Florida), so the plan in case of a catastrophic launch

accident on the pad essentially seemed to be “hope that

never happens”. In any case, after spending more than

US$4 billion on the facilities, after the Challenger

disaster in 1986, plans for Shuttle launches from Vandenberg

were abandoned, and the facility was mothballed until being

adapted, years later, to launch other rockets.

This book, part of the “Images of America” series,

is a collection of photographs (all black and white) covering

all aspects of the history of the site from before World War II

to the present day. Introductory text for each chapter and

detailed captions describe the items shown and their

significance to the base's history. The production quality is

excellent, and I noted only one factual error in the text (the

names of crew of Gemini 5). For a book of just 128 pages, the

paperback is very expensive (US$22 at this writing). The

Kindle edition is still pricey (US$13

list price), but may be read for free by Kindle Unlimited

subscribers.

- Andrew, Christopher and Vasili Mitrokhin.

The Sword and the Shield.

New York: Basic Books, 1999.

ISBN 978-0-465-00312-9.

-

Vasili Mitrokhin joined the Soviet intelligence service as a

foreign intelligence officer in 1948, at a time when the MGB

(later to become the KGB) and the GRU were unified into a single

service called the Committee of Information. By the time he was

sent to his first posting abroad in 1952, the two services had

split and Mitrokhin stayed with the MGB. Mitrokhin's career

began in the paranoia of the final days of Stalin's regime, when

foreign intelligence officers were sent on wild goose chases

hunting down imagined Trotskyist and Zionist conspirators

plotting against the regime. He later survived the turbulence

after the death of Stalin and the execution of MGB head Lavrenti

Beria, and the consolidation of power under his successors.

During the Khrushchev years, Mitrokhin became disenchanted

with the regime, considering Khrushchev an uncultured

barbarian whose banning of avant garde writers betrayed

the tradition of Russian literature. He began to entertain

dissident thoughts, not hoping for an overthrow of the Soviet

regime but rather its reform by a new generation of leaders

untainted by the legacy of Stalin. These thoughts were

reinforced by the crushing of the reform-minded regime

in Czechoslovakia in 1968 and his own observation of how

his service, now called the KGB, manipulated the Soviet

justice system to suppress dissent within the Soviet

Union. He began to covertly listen to Western broadcasts

and read samizdat publications by Soviet dissidents.

In 1972, the First Chief Directorate (FCD: foreign intelligence)

moved from the cramped KGB headquarters in the Lubyanka

in central Moscow to a new building near the ring road.

Mitrokhin had sole responsibility for checking, inventorying,

and transferring the entire archives, around 300,000 documents,

of the FCD for transfer to the new building. These files

documented the operations of the KGB and its predecessors

dating back to 1918, and included the most secret records,

those of Directorate S, which ran “illegals”:

secret agents operating abroad under false identities.

Probably no other individual ever read as many

of the KGB's most secret archives as Mitrokhin. Appalled

by much of the material he reviewed, he covertly began to

make his own notes of the details. He started by committing

key items to memory and then transcribing them every evening

at home, but later made covert notes on scraps of paper

which he smuggled out of KGB offices in his shoes.

Each week-end he would take the notes to his dacha outside

Moscow, type them up, and hide them in a series of locations

which became increasingly elaborate as their volume grew.

Mitrokhin would continue to review, make notes, and add them

to his hidden archive for the next twelve years until his

retirement from the KGB in 1984. After Mikhail Gorbachev

became party leader in 1985 and called for more openness

(glasnost), Mitrokhin,

shaken by what he had seen in the files regarding Soviet

actions in Afghanistan, began to think of ways he might

spirit his files out of the Soviet Union and publish

them in the West.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Mitrokhin tested the new

freedom of movement by visiting the capital of one of the

now-independent Baltic states, carrying a sample of the material

from his archive concealed in his luggage. He crossed the

border with no problems and walked in to the British embassy to

make a deal. After several more trips, interviews with British

Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) officers, and providing more

sample material, the British agreed to arrange the exfiltration

of Mitrokhin, his entire family, and the entire

archive—six cases of notes. He was debriefed at a series

of safe houses in Britain and began several years of work typing

handwritten notes, arranging the documents, and answering

questions from the SIS, all in complete secrecy. In 1995, he

arranged a meeting with Christopher Andrew, co-author of the

present book, to prepare a history of KGB foreign intelligence

as documented in the archive.

Mitrokhin's exfiltration (I'm not sure one can call it a

“defection”, since the country whose information he

disclosed ceased to exist before he contacted the British) and

delivery of the archive is one of the most stunning intelligence

coups of all time, and the material he delivered will be an

essential primary source for historians of the twentieth

century. This is not just a whistle-blower disclosing

operations of limited scope over a short period of time, but an

authoritative summary of the entire history of the foreign

intelligence and covert operations of the Soviet Union from its

inception until the time it began to unravel in the mid-1980s.

Mitrokhin's documents name names; identify agents, both

Soviet and recruits in other countries, by codename; describe

secret operations, including assassinations, subversion,

“influence operations” planting propaganda in

adversary media and corrupting journalists and politicians,

providing weapons to insurgents, hiding caches of weapons and

demolition materials in Western countries to support special

forces in case of war; and trace the internal politics and conflicts

within the KGB and its predecessors and with the Party and

rivals, particularly military intelligence (the GRU).

Any doubts about the degree of penetration of Western

governments by Soviet intelligence agents are laid to rest by

the exhaustive documentation here. During the 1930s and

throughout World War II, the Soviet Union had highly-placed

agents throughout the British and American governments, military,

diplomatic and intelligence communities, and science and

technology projects. At the same time, these supposed allies had

essentially zero visibility into the Soviet Union: neither

the American OSS nor the British SIS had a single agent in

Moscow.

And yet, despite success in infiltrating other countries

and recruiting agents within them (particularly prior to

the end of World War II, when many agents, such as the

“Magnificent

Five” [Donald Maclean, Kim Philby,

John Cairncross, Guy Burgess, and Anthony Blunt] in

Britain, were motivated by idealistic admiration for the

Soviet project, as opposed to later, when sources tended

to be in it for the money), exploitation of this vast

trove of purloined secret information was uneven and

often ineffective. Although it reached its apogee during

the Stalin years, paranoia and intrigue are as Russian as borscht,

and compromised the interpretation and use of intelligence

throughout the history of the Soviet Union. Despite having

loyal spies in high places in governments around the world,

whenever an agent provided information which seemed “too

good” or conflicted with the preconceived notions of

KGB senior officials or Party leaders, it was likely to be

dismissed as disinformation, often suspected to have been planted

by British counterintelligence, to which the Soviets

attributed almost supernatural powers, or that their agents had

been turned and were feeding false information to the Centre.

This was particularly evident during the period prior to the

Nazi attack on the Soviet Union in 1941. KGB archives record

more than a hundred warnings of preparations for the attack having

been forwarded to Stalin between January and June 1941, all

of which were dismissed as disinformation or erroneous due to

Stalin's idée fixe that

Germany would not attack because it was too dependent on raw

materials supplied by the Soviet Union and would not

risk a two front war while Britain remained undefeated.

Further, throughout the entire history of the Soviet Union,

the KGB was hesitant to report intelligence which

contradicted the beliefs of its masters in the Politburo

or documented the failures of their policies and initiatives.

In 1985, shortly after coming to power, Gorbachev lectured

KGB leaders “on the impermissibility of distortions of

the factual state of affairs in messages and informational

reports sent to the Central Committee of the CPSU and other

ruling bodies.”

Another manifestation of paranoia was deep suspicion of

those who had spent time in the West. This meant that often

the most effective agents who had worked undercover in the

West for many years found their reports ignored due to fears

that they had “gone native” or been doubled by

Western counterintelligence. Spending too much time on

assignment in the West was not conducive to advancement

within the KGB, which resulted in the service's senior

leadership having little direct experience with the West and

being prone to fantastic misconceptions about the institutions

and personalities of the adversary. This led to delusional

schemes such as the idea of recruiting stalwart anticommunist

senior figures such as Zbigniew Brzezinski as KGB agents.

This is a massive compilation of data: 736 pages in the

paperback edition, including almost 100 pages of

detailed end notes and source citations. I would be less

than candid if I gave the impression that this reads like

a spy thriller: it is nothing of the sort. Although such

information would have been of immense value during the

Cold War, long lists of the handlers who worked with

undercover agents in the West, recitations of codenames

for individuals, and exhaustive descriptions of now

largely forgotten episodes such as the KGB's campaign

against “Eurocommunism” in the 1970s and 1980s,

which it was feared would thwart Moscow's control over

communist parties in Western Europe, make for heavy

going for the reader.

The KGB's operations in the West were far from flawless.

For decades, the Communist Party of the United States

(CPUSA) received substantial subsidies from the KGB

despite consistently promising great breakthroughs and

delivering nothing. Between the 1950s and 1975, KGB

money was funneled to the CPUSA through two undercover

agents, brothers named Morris and Jack Childs,

delivering cash often exceeding a million dollars a

year. Both brothers were awarded the Order of the Red

Banner in 1975 for their work, with Morris receiving his

from Leonid Brezhnev in person. Unbeknownst to the KGB,

both of the Childs brothers had been working for, and

receiving salaries from, the FBI since the early 1950s,

and reporting where the money came from and went—well,

not the five percent they embezzled before passing it on.

In the 1980s, the KGB increased the CPUSA's subsidy to

two million dollars a year, despite the party's never

having more than 15,000 members (some of whom, no

doubt, were FBI agents).

A second doorstop of a book (736 pages) based upon the Mitrokhin

archive,

The World Was Going our Way,

published in 2005, details the KGB's operations in the Third

World during the Cold War. U.S. diplomats who regarded the globe

and saw communist subversion almost everywhere were accurately

reporting the situation on the ground, as the KGB's own files

reveal.

The Kindle edition is free for Kindle

Unlimited subscribers.