Economics

- Ahamed, Liaquat. Lords of Finance. New York: Penguin Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-14-311680-6.

- I have become increasingly persuaded that World War I was the singular event of the twentieth century in that it was not only an unprecedented human tragedy in its own right (and utterly unnecessary), it set in motion the forces which would bring about the calamities which would dominate the balance of the century and which still cast dark shadows on our world as it approaches one century after that fateful August. When the time comes to write the epitaph of the entire project of the Enlightenment (assuming its successor culture permits it to even be remembered, which is not the way to bet), I believe World War I will be seen as the moment when it all began to go wrong. This is my own view, not the author's thesis in this book, but it is a conclusion I believe is strongly reinforced by the events chronicled here. The present volume is a history of central banking in Europe and the U.S. from the years prior to World War I through the institution of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates based on U.S. dollar reserves backed by gold. The story is told through the careers of the four central bankers who dominated the era: Montagu Norman of the Bank of England, Émile Moreau of la Banque de France, Hjalmar Schact of the German Reichsbank, and Benjamin Strong of the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Prior to World War I, central banking, to the extent it existed at all in anything like the modern sense, was a relatively dull field of endeavour performed by correspondingly dull people, most aristocrats or scions of wealthy families who lacked the entrepreneurial bent to try things more risky and interesting. Apart from keeping the system from seizing up in the occasional financial panic (which was done pretty much according to the playbook prescribed in Walter Bagehot's Lombard Street, published in 1873), there really wasn't a lot to do. All of the major trading nations were on a hard gold standard, where their paper currency was exchangeable on demand for gold coin or bullion at a fixed rate. This imposed rigid discipline upon national governments and their treasuries, since any attempt to inflate the money supply ran the risk of inciting a run on their gold reserves. Trade imbalances would cause a transfer of gold which would force partners to adjust their interest rates, automatically cooling off overheated economies and boosting those suffering slowdowns. World War I changed everything. After the guns fell silent and the exhausted nations on both sides signed the peace treaties, the financial landscape of the world was altered beyond recognition. Germany was obliged to pay reparations amounting to a substantial fraction of its GDP for generations into the future, while both Britain and France had run up debts with the United States which essentially cleaned out their treasuries. The U.S. had amassed a hoard of most of the gold in the world, and was the only country still fully on the gold standard. As a result of the contortions done by all combatants to fund their war efforts, central banks, which had been more or less independent before the war, became increasingly politicised and the instruments of government policy. The people running these institutions, however, were the same as before: essentially amateurs without any theoretical foundation for the policies this unprecedented situation forced them to formulate. Germany veered off into hyperinflation, Britain rejoined the gold standard at the prewar peg of the pound, resulting in disastrous deflation and unemployment, while France revalued the franc against gold at a rate which caused the French economy to boom and gold to start flowing into its coffers. Predictably, this led to crisis after crisis in the 1920s, to which the central bankers tried to respond with Band-Aid after Band-Aid without any attempt to fix the structural problems in the system they had cobbled together. As just one example, an elaborate scheme was crafted where the U.S. would loan money to Germany which was used to make reparation payments to Britain and France, who then used the proceeds to repay their war debts to the U.S. Got it? (It was much like the “petrodollar recycling” of the 1970s where the West went into debt to purchase oil from OPEC producers, who would invest the money back in the banks and treasury securities of the consumer countries.) Of course, the problem with such schemes is there's always that mountain of debt piling up somewhere, in this case in Germany, which can't be repaid unless the economy that's straining under it remains prosperous. But until the day arrives when the credit card is maxed out and the bill comes due, things are glorious. After that, not so much—not just bad, but Hitler bad. This is a fascinating exploration of a little-known epoch in monetary history, and will give you a different view of the causes of the U.S. stock market bubble of the 1920s, the crash of 1929, and the onset of the First Great Depression. I found the coverage of the period a bit uneven: the author skips over much of the financial machinations of World War I and almost all of World War II, concentrating on events of the 1920s which are now all but forgotten (not that there isn't a great deal we can learn from them). The author writes from a completely conventional wisdom Keynesian perspective—indeed Keynes is a hero of the story, offstage for most of it, arguing that flawed monetary policy was setting the stage for disaster. The cause of the monetary disruptions in the 1920s and the Depression is attributed to the gold standard, and yet even the most cursory examination of the facts, as documented in the book itself, gives lie to this. After World War I, there was a gold standard in name only, as currencies were manipulated at the behest of politicians for their own ends without the discipline of the prewar gold standard. Further, if the gold standard caused the Depression, why didn't the Depression end when all of the major economies were forced off the gold standard by 1933? With these caveats, there is a great deal to be learned from this recounting of the era of the first modern experiment in political control of money. We are still enduring its consequences. One fears the “maestros” trying to sort out the current mess have no more clue what they're doing than the protagonists in this account. In the Kindle edition the table of contents and end notes are properly linked to the text, but source citations, which are by page number in the print edition, are not linked. However, locations in the book are given both by print page number and Kindle “location”, so you can follow them, albeit a bit tediously, if you wish to. The index is just a list of terms without links to their appearances in the text.

- Beck, Glenn and Harriet Parke. Agenda 21. New York: Threshold Editions, 2012. ISBN 978-1-4767-1669-5.

- In 1992, at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (“Earth Summit”) in Rio de Janeiro, an action plan for “sustainable development” titled “Agenda 21” was adopted. It has since been endorsed by the governments of 178 countries, including the United States, where it was signed by president George H. W. Bush (not being a formal treaty, it was not submitted to the Senate for ratification). An organisation called Local Governments for Sustainability currently has more than 1200 member towns, cities, and counties in 70 countries, including more than 500 in the United States signed on to the program. Whenever you hear a politician talking about environmental “sustainability” or the “precautionary principle”, it's a good bet the ideas they're promoting can be traced back to Agenda 21 or its progenitors. When you read the U.N. Agenda 21 document (which I highly encourage you to do—it is very likely your own national government has endorsed it), it comes across as the usual gassy international bureaucratese you expect from a U.N. commission, but if you read between the lines and project the goals and mechanisms advocated to their logical conclusions, the implications are very great indeed. What is envisioned is nothing less than the extinction of the developed world and the roll-back of the entire project of the enlightenment. While speaking of the lofty goal of lifting the standard of living of developing nations to that of the developed world in a manner that does not damage the environment, it is an inevitable consequence of the report's assumption of finite resources and an environment already stressed beyond the point of sustainability that the inevitable outcome of achieving “equity” will be a global levelling of the standard of living to one well below the present-day mean, necessitating a catastrophic decrease in the quality of life in developed nations, which will almost certainly eliminate their ability to invest in the research and technological development which have been the engine of human advancement since the Renaissance. The implications of this are so dire that somebody ought to write a dystopian novel about the ultimate consequences of heading down this road. Somebody has. Glenn Beck and Harriet Parke (it's pretty clear from the acknowledgements that Parke is the principal author, while Beck contributed the afterword and lent his high-profile name to the project) have written a dark and claustrophobic view of what awaits at the end of The Road to Serfdom (May 2002). Here, as opposed to an incremental shift over decades, the United States experiences a cataclysmic socio-economic collapse which is exploited to supplant it with the Republic, ruled by the Central Authority, in which all Citizens are equal. The goals of Agenda 21 have been achieved by depopulating much of the land, letting it return to nature, packing the humans who survived the crises and conflict as the Republic consolidated its power into identical densely-packed Living Spaces, where they live their lives according to the will of the Authority and its Enforcers. Citizens are divided into castes by job category; reproductive age Citizens are “paired” by the Republic, and babies are taken from mothers at birth to be raised in Children's Villages, where they are indoctrinated to serve the Republic. Unsustainable energy sources are replaced by humans who have to do their quota of walking on “energy board” treadmills or riding “energy bicycles” everywhere, and public transportation consists of bus boxes, pulled by teams of six strong men. Emmeline has grown up in this grim and grey world which, to her, is way things are, have always been, and always will be. Just old enough at the establishment of Republic to escape the Children's Village, she is among the final cohort of Citizens to have been raised by their parents, who told her very little of the before-time; speaking of that could imperil both parents and child. After she loses both parents (people vanishing, being “killed in industrial accidents”, or led away by Enforcers never to be seen again is common in the Republic), she discovers a legacy from her mother which provides a tenuous link to the before-time. Slowly and painfully she begins to piece together the history of the society in which she lives and what life was like before it descended to crush the human spirit. And then she must decide what to do about it. I am sure many reviewers will dismiss this novel as a cartoon-like portrayal of ideas taken to an absurd extreme. But much the same could have been said of We, Anthem, or 1984. But the thing about dystopian novels based upon trends already in place is that they have a disturbing tendency to get things right. As I observed in my review of Atlas Shrugged (April 2010), when I first read it in 1968, it seemed to evoke a dismal future entirely different from what I expected. When I read it the third time in 2010, my estimation was that real-world events had taken us about 500 pages into the 1168 page tome. I'd probably up that number today. What is particularly disturbing about the scenario in this novel, as opposed to the works cited above, is that it describes what may be a very strong attractor for human society once rejection of progress becomes the doctrine and the population stratifies into a small ruling class and subjects entirely dependent upon the state. After all, that's how things have more or less been over most of human history and around the globe, and the brief flash of liberty, innovation, and prosperity we assume to be the normal state of affairs may simply be an ephemeral consequence of the opening of a frontier which, now having closed, concludes that aberrant chapter of history, soon to be expunged and forgotten. This is a book which begs for one or more sequels. While the story is satisfying by itself, you put it down wondering what happens next, and what is going on outside the confines of the human hive its characters inhabit. Who are the members of the Central Authority? How do they live? How do they groom their successors? What is happening on other continents? Is there any hope the torch of liberty might be reignited? While doubtless many will take fierce exception to the entire premise of the story, I found only one factual error. In chapter 14 Emmeline discovers a photograph which provides a link to the before-time. On it is the word “KODACHROME”. But Kodachrome was a colour slide (reversal) film, not a colour print film. Even if the print that Emmeline found had been made from a Kodachrome slide, the print wouldn't say “KODACHROME”. I did not spot a single typographical error, and if you're a regular reader of this chronicle, you'll know how rare that is. In the Kindle edition, links to documents and resources cited in the factual afterword are live and will take you directly to the cited page.

- Bernstein, Peter L. Against the Gods. New York: John Wiley & Sons, [1996] 1998. ISBN 978-0-471-29563-1.

- I do not use the work “masterpiece” lightly, but this is what we have here. What distinguishes the modern epoch from all of the centuries during which humans identical to us trod this Earth? The author, a distinguished and erudite analyst and participant in the securities markets over his long career, argues that one essential invention of the modern era, enabling the vast expansion of economic activity and production of wealth in Western civilisation, is the ability to comprehend, quantify, and ultimately mitigate risk, either by commingling independent risks (as does insurance), or by laying risk off from those who would otherwise bear it onto speculators willing to assume it in the interest of financial gains (for example, futures, options, and other financial derivatives). If, as in the classical world, everyone bears the entire risk of any undertaking, then all market players will be risk-averse for fear of ruin. But if risk can be shared, then the society as a whole will be willing to run more risks, and it is risks voluntarily assumed which ultimately lead (after the inevitable losses) to net gain for all. So curious and counterintuitive are the notions associated with risk that understanding them took centuries. The ancients, who made such progress in geometry and other difficult fields of mathematics, were, while avid players of games of chance, inclined to attribute the outcome to the will of the Gods. It was not until the Enlightenment that thinkers such as Pascal, Cardano, the many Bernoullis, and others worked out the laws of probability, bringing the inherent randomness of games of chance into a framework which predicted the outcome, not of any given event—that was unknowable in principle, but the result of a large number of plays with arbitrary precision as the number of trials increased. Next was the understanding of the importance of uncertainty in decision making. It's one thing not to know whether a coin will come up heads or tails. It's entirely another to invest in a stock and realise that however accurate your estimation of the probabilistic unknowns affecting its future (for example, the cost of raw materials), it's the “unknown unknowns” (say, overnight bankruptcy due to a rogue trader in an office half way around the world) that can really sink your investment. Finally, classical economics always assumed that participants in the market behave rationally, but they don't. Anybody who thinks their fellow humans are rational need only visit a casino or watch them purchasing lottery tickets; they are sure in the long term to lose, and yet they still line up to make the sucker bet. Somehow, I'd gotten it into my head that this was a “history of insurance”, and as a result this book sat on my shelf quite some time before I read it. It is much, much more than that. If you have any interest at all in investing, risk management in business ventures, or in the history of probability, statistics, game theory, and investigations of human behaviour in decision making, this is an essential book. Chapter 18 is one of the clearest expositions for its length that I've read of financial derivatives and both the benefits they have for prudent investors as well as the risks they pose to the global financial system. The writing is delightful, and sources are well documented in end notes and an extensive bibliography.

- Bonner, William with Addison Wiggin. Financial Reckoning Day. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2003. ISBN 0-471-44973-3.

- William Bonner's Daily Reckoning newsletter was, along with a few others like Downside, a voice of sanity in the bubble markets of the turn of millennium. I've always found that the best investment analysis looks well beyond the markets to the historical, social, political, moral, technological, and demographic trends which market action ultimately reflects. Bonner and Wiggin provide a global, multi-century tour d'horizon here, and make a convincing case that the boom, bust, and decade-plus “soft depression” which Japan suffered from the 1990s to the present is the prototype of what's in store for the U.S. as the inevitable de-leveraging of the mountain of corporate and consumer debt on which the recent boom was built occurs, with the difference that Japan has the advantage of a high savings rate and large trade surplus, while the U.S. saves nothing and runs enormous trade deficits. The analysis of how Alan Greenspan's evolution from supreme goldbug in Ayn Rand's inner circle to maestro of paper money is completely consistent with his youthful belief in Objectivism is simply delightful. The authors readily admit that markets can do anything, but believe that in the long run, markets generally do what they “ought to”, and suggest an investment strategy for the next decade on that basis.

- Bonner, William and Addison Wiggin. Empire of Debt. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2006. ISBN 0-471-73902-2.

- To make any sense in the long term, an investment strategy needs to be informed by a “macro macro” view of the global economic landscape and the grand-scale trends which shape it, as well as a fine sense for nonsense: the bubbles, manias, and unsustainable situations which seduce otherwise sane investors into doing crazy things which will inevitably end badly, although nobody can ever be sure precisely when. This is the perspective the authors provide in this wise, entertaining, and often laugh-out-loud funny book. If you're looking for tips on what stocks or funds to buy or sell, look elsewhere; the focus here is on the emergence in the twentieth century of the United States as a global economic and military hegemon, and the bizarre economic foundations of this most curious empire. The analysis of the current scene is grounded in a historical survey of empires and a recounting of how the United States became one. The business of empire has been conducted more or less the same way all around the globe over millennia. An imperial power provides a more or less peaceful zone to vassal states, a large, reasonably open market in which they can buy and sell their goods, safe transport for goods and people within the imperial limes, and a common currency, system of weights and measures, and other lubricants of efficient commerce. In return, vassal states finance the empire through tribute: either explicit, or indirectly through taxes, tariffs, troop levies, and other imperial exactions. Now, history is littered with the wreckage of empires (more than fifty are listed on p. 49), which have failed in the time-proven ways, but this kind of traditional empire at least has the advantage that it is profitable—the imperial power is compensated for its services (whether welcome or appreciated by the subjects or not) by the tribute it collects from them, which may be invested in further expanding the empire. The American empire, however, is unique in all of human history for being funded not by tribute but by debt. The emergence of the U.S. dollar as the global reserve currency, severed from the gold standard or any other measure of actual value, has permitted the U.S. to build a global military presence and domestic consumer society by borrowing the funds from other countries (notably, at the present time, China and Japan), who benefit (at least in the commercial sense) from the empire. Unlike tribute, the debt remains on the balance sheet as an exponentially growing liability which must eventually either be repaid or repudiated. In this environment, international trade has become a system in which (p. 221) “One nation buys things that it cannot afford and doesn't need with money it doesn't have. Another sells on credit to people who already cannot pay and then builds more factories to increase output.” Nobody knows how long the game can go on, but when it ends, it is certain to end badly. An empire which has largely ceased to produce stuff for its citizens, whose principal export has become paper money (to the tune of about two billion dollars per day at this writing), will inevitably succumb to speculative binges. No sooner had the dot.com mania of the late 1990s collapsed than the residential real estate bubble began to inflate, with houses bought with interest-only mortgages considered “investments” which are “flipped” in a matter of months, and equity extracted by further assumption of debt used to fund current consumption. This contemporary collective delusion is well documented, with perspectives on how it may end. The entire book is written in an “always on” ironic style, with a fine sense for the absurdities which are taken for wisdom and the charlatans and nincompoops who peddle them to the general public in the legacy media. Some may consider the authors' approach as insufficiently serious for a discussion of an oncoming global financial train wreck but, as they note on p. 76, “There is nothing quite so amusing as watching another man make a fool of himself. That is what makes history so entertaining.” Once you get your head out of the 24 hour news cycle and the political blogs and take the long view, the economic and geopolitical folly chronicled here is intensely entertaining, and the understanding of it imparted in this book is valuable in developing a strategy to avoid its inevitable tragic consequences.

- Caplan, Bryan. The Myth of the Rational Voter. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-691-13873-2.

- Every survey of the electorate in Western democracies shows it to be woefully uninformed: few can name their elected representatives or identify their party affiliation, nor answer the most basic questions about the political system under which they live. Economists and political scientists attribute this to “rational ignorance”: since there is a vanishingly small probability that the vote of a single person will be decisive, it is rational for that individual to ignore the complexities of the issues and candidates and embrace the cluelessness which these polls make manifest. But, the experts contend, there's no problem—even if a large majority of the electorate is ignorant knuckle-walkers, it doesn't matter because they'll essentially vote at random. Their uninformed choices will cancel out, and the small informed minority will be decisive. Hence the “miracle of aggregation”: stir in millions of ignoramuses and thousands of political junkies and diligent citizens and out pops true wisdom. Or maybe not—this book looks beyond the miracle of aggregation, which assumes that the errors of the uninformed are random, to examine whether there are systematic errors (or biases) among the general population which cause democracies to choose policies which are ultimately detrimental to the well-being of the electorate. The author identifies four specific biases in the field of economics, and documents, by a detailed analysis of the Survey of Americans and Economists on the Economy , that while economists, reputed to always disagree amongst themselves, are in fact, on issues which Thomas Sowell terms Basic Economics (September 2008), almost unanimous in their opinions, yet widely at variance from the views of the general public and the representatives they elect. Many economists assume that the electorate votes what economists call its “rational choice”, yet empirical data presented here shows that democratic electorates behave very differently. The key insight is that choice in an election is not a preference in a market, where the choice directly affects the purchaser, but rather an allocation in a commons, where the consequences of an individual vote have negligible results upon the voter who casts it. And we all know how commons inevitably end. The individual voter in a large democratic polity bears a vanishingly small cost in voting their ideology or beliefs, even if they are ultimately damaging to their own well-being, because the probability their own single vote will decide the election is infinitesimal. As a result, the voter is liberated to vote based upon totally irrational beliefs, based upon biases shared by a large portion of the electorate, insulated by the thought, “At least my vote won't decide the election, and I can feel good for having cast it this way”. You might think that voters would be restrained from indulging their feel-good inclinations by considering their self interest, but studies of voter behaviour and the preferences of subgroups of voters demonstrate that in most circumstances voters support policies and candidates they believe are best for the polity as a whole, not their narrow self interest. Now, this would be a good thing if their beliefs were correct, but at least in the field of economics, they aren't, as defined by the near-unanimous consensus of professional economists. This means that there is a large, consistent, systematic bias in policies preferred by the uninformed electorate, whose numbers dwarf the small fraction who comprehend the issues in contention. And since, once again, there is no cost to an individual voter in expressing his or her erroneous beliefs, the voter can be “rationally irrational”: the possibility of one vote being decisive vanishes next to the cost of becoming informed on the issues, so it is rational to unknowingly vote irrationally. The reason democracies so often pursue irrational policies such as protectionism is not unresponsive politicians or influence of special interests, but instead politicians giving the electorate what it votes for, which is regrettably ultimately detrimental to its own self-interest. Although the discussion here is largely confined to economic issues, there is no reason to believe that this inherent failure of democratic governance is confined to that arena. Indeed, one need only peruse the daily news to see abundant evidence of democracies committing folly with the broad approbation of their citizenry. (Run off a cliff? Yes, we can!) The author contends that rational irrationality among the electorate is an argument for restricting the scope of government and devolving responsibilities it presently undertakes to market mechanisms. In doing so, the citizen becomes a consumer in a competitive market and now has an individual incentive to make an informed choice because the consequences of that choice will be felt directly by the person making it. Naturally, as you'd expect with an irrational electorate, things seem to have been going in precisely the opposite direction for much of the last century. This is an excellently argued and exhaustively documented book (The ratio of pages of source citations and end notes to main text may be as great as anything I've read) which will make you look at democracy in a different way and begin to comprehend that in many cases where politicians do stupid things, they are simply carrying out the will of an irrational electorate. For a different perspective on the shortcomings of democracy, also with a primary focus on economics, see Hans-Hermann Hoppe's superb Democracy: The God that Failed (June 2002), which approaches the topic from a hard libertarian perspective.

- Cox, Joseph. The City on the Heights. Modiin, Israel: Big Picture Books, 2017. ISBN 978-0-9764659-6-6.

- For more than two millennia the near east (which is sloppily called the “middle east” by ignorant pundits who can't distinguish north Africa from southwest Asia) has exported far more trouble than it has imported from elsewhere. You need only consult the chronicles of the Greeks, the Roman Empire, the histories of conflicts among them and the Persians, the expansion of Islam into the region, internecine conflicts among Islamic sects, the Crusades, Israeli-Arab wars, all the way to recent follies of “nation building” to appreciate that this is a perennial trouble spot. People, and peoples hate one another there. It seems like whenever you juxtapose two religions (even sects of one), ethnicities, or self-identifications in the region, before long sanguinary conflict erupts, with each incident only triggering even greater reprisals and escalation. In the words of Lenin, What is to be done? Now, my inclination would be simply to erect a strong perimeter around the region, let anybody who wished enter, but nobody leave without extreme scrutiny to ensure they were not a risk and follow-up as long as they remained as guests in the civilised regions of the world. This is how living organisms deal with threats to their metabolism: encyst upon it! In this novel, the author explores another, more hopeful and optimistic, yet perhaps less realistic alternative. When your computer ends up in a hopeless dead-end of resource exhaustion, flailing software, and errors in implementation, you reboot it, or turn it off and on again. This clears out the cobwebs and provides a fresh start. It's difficult to do this in a human community, especially one where grievances are remembered not just over generations but millennia. Here, archetypal NGO do-gooder Steven Gold has another idea. In the midst of the European religious wars, Amsterdam grew and prospered by being a place that people of any faith could come together and do business. Notwithstanding having a nominal established religion, people of all confessions were welcome as long as they participated in the peaceful commerce and exchange which made the city prosper. Could this work in the near east? Steven Gold thought it was worth a try, and worth betting his career upon. But where should such a model city be founded? The region was a nightmarish ever-shifting fractal landscape of warring communities with a sole exception: the state of Israel. Why on Earth would Israel consider ceding some of its territory (albeit mostly outside its security perimeter) for such an idealistic project which might prove to be a dagger aimed at its own heart? Well, Steven Gold is very persuasive, and talented at recruiting allies able to pitch the project in terms those needed to support it understand. And so, a sanctuary city on the Israel-Syria border is born. It is anything but a refugee camp. Residents are expected to become productive members of a multicultural, multi-ethnic community which will prosper along the lines of renaissance Amsterdam or, more recently, Hong Kong and Singapore. Those who wish to move to the City are carefully vetted, but they include a wide variety of people including a former commander of the Islamic State, a self-trained engineer and problem solver who is an escapee from a forced marriage, religious leaders from a variety of faiths, and supporters including a billionaire who made her fortune in Internet payment systems. And then, since it's the near east, it all blows up. First there are assassinations, then bombings, then a sorting out into ethnic and sectarian districts within the city, and then reprisals. It almost seems like an evil genius is manipulating the communities who came there to live in peace and prosper into conflict among one another. That this might be possible never enters the mind of Steven Gold, who probably still believes in the United Nations and votes for Democrats, notwithstanding their resolute opposition to the only consensual democracy in the region. Can an act of terrorism redeem a community? Miryam thinks so, and acts accordingly. As the consequences play out, and the money supporting the city begins to run out, a hierarchical system of courts which mix up the various contending groups is established, and an economic system based upon electronic payments which provides a seamless transition between subsidies for the poor (but always based upon earned income: never a pure dole) and taxation for the more prosperous. A retrospective provides a look at how it all might work. I remain dubious at the prospect. There are many existing communities in the near east which are largely homogeneous in terms of religion and ethnicity (as seen by outsiders) which might be prosperous if they didn't occupy themselves with bombing and killing one another by any means available, and yet the latter is what they choose to do. Might it be possible, by establishing sanctuaries, to select for those willing to set ancient enmities aside? Perhaps, but in this novel, grounded in reality, that didn't happen. The economic system is intriguing but, to me, ultimately unpersuasive. I understand how the income subsidy encourages low-income earners to stay within the reported income economy, but the moment you cross the tax threshold, you have a powerful incentive to take things off the books and, absent some terribly coercive top-down means to force all transactions through the electronic currency system, free (non-taxed) exchange will find a way. These quibbles aside, this is a refreshing and hopeful look at an alternative to eternal conflict. In the near east, “the facts on the ground” are everything and the author, who lives just 128 km from the centre of civil war in Syria is far more acquainted with the reality than somebody reading his book far away. I hope his vision is viable. I hope somebody tries it. I hope it works.

- Fergusson, Adam. When Money Dies. New York: PublicAffairs, [1975] 2010. ISBN 978-1-58648-994-6.

-

This classic work, originally published in 1975, is the definitive history of the great inflation in Weimar Germany, culminating in the archetypal paroxysm of hyperinflation in the Fall of 1923, when Reichsbank printing presses were cranking out 100 trillion (1012) mark banknotes as fast as paper could be fed to them, and government expenditures were 6 quintillion (1018) marks while, in perhaps the greatest achievement in deficit spending of all time, revenues in all forms accounted for only 6 quadrillion (1015) marks. The book has long been out of print and much in demand by students of monetary madness, driving the price of used copies into the hundreds of dollars (although, to date, not trillions and quadrillions—patience). Fortunately for readers interested in the content and not collectibility, the book has been re-issued in a new paperback and electronic edition, just as inflation has come back onto the radar in the over-leveraged economies of the developed world. The main text is unchanged, and continues to use mid-1970s British nomenclature for large numbers (“millard” for 109, “billion” for 1012 and so on) and pre-decimalisation pounds, shillings, and pence for Sterling values. A new note to this edition explains how to convert the 1975 values used in the text to their approximate present-day equivalents.

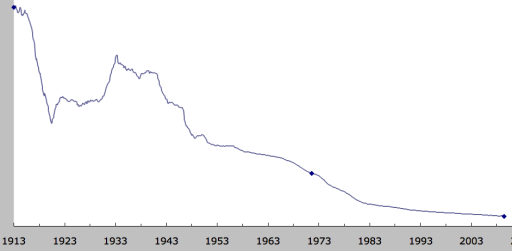

The Weimar hyperinflation is an oft-cited turning point in twentieth century, but like many events of that century, much of the popular perception and portrayal of it in the legacy media is incorrect. This work is an in-depth antidote to such nonsense, concentrating almost entirely upon the inflation itself, and discussing other historical events and personalities only when relevant to the main topic. To the extent people are aware of the German hyperinflation at all, they'll usually describe it as a deliberate and cynical ploy by the Weimar Republic to escape the reparations for World War I exacted under the Treaty of Versailles by inflating away the debt owed to the Allies by debasing the German mark. This led to a cataclysmic episode of hyperinflation where people had to take a wheelbarrow of banknotes to the bakery to buy a loaf of bread and burning money would heat a house better than the firewood or coal it would buy. The great inflation and the social disruption it engendered led directly to the rise of Hitler. What's wrong with this picture? Well, just about everything…. Inflation of the German mark actually began with the outbreak of World War I in 1914 when the German Imperial government, expecting a short war, decided to finance the war effort by deficit spending and printing money rather than raising taxes. As the war dragged on, this policy continued and was reinforced, since it was decided that adding heavy taxes on top of the horrific human cost and economic privations of the war would be disastrous to morale. As a result, over the war years of 1914–1918 the value of the mark against other currencies fell by a factor of two and was halved again in the first year of peace, 1919. While Germany was committed to making heavy reparation payments, these payments were denominated in gold, not marks, so inflating the mark did nothing to reduce the reparation obligations to the Allies, and thus provided no means of escaping them. What inflation and the resulting cheap mark did, however, was to make German exports cheap on the world market. Since export earnings were the only way Germany could fund reparations, promoting exports through inflation was both a way to accomplish this and to promote social peace through full employment, which was in fact achieved through most of the early period of inflation. By early 1920 (well before the hyperinflationary phase is considered to have kicked in), the mark had fallen to one fortieth of its prewar value against the British pound and U.S. dollar, but the cost of living in Germany had risen only by a factor of nine. This meant that German industrialists and their workers were receiving a flood of marks for the products they exported which could be spent advantageously on the domestic market. Since most of Germany's exports at the time relied little on imported raw materials and products, this put Germany at a substantial advantage in the world market, which was much remarked upon by British and French industrialists at the time, who were prone to ask, “Who won the war, anyway?”. While initially beneficial to large industry and its organised labour force which was in a position to negotiate wages that kept up with the cost of living, and a boon to those with mortgaged property, who saw their principal and payments shrink in real terms as the currency in which they were denominated declined in value, the inflation was disastrous to pensioners and others on fixed incomes denominated in marks, as their standard of living inexorably eroded. The response of the nominally independent Reichsbank under its President since 1908, Dr. Rudolf Havenstein, and the German government to these events was almost surreally clueless. As the originally mild inflation accelerated into dire inflation and then headed vertically on the exponential curve into hyperinflation they universally diagnosed the problem as “depreciation of the mark on the foreign exchange market” occurring for some inexplicable reason, which resulted in a “shortage of currency in the domestic market”, which could only be ameliorated by the central bank's revving up its printing presses to an ever-faster pace and issuing notes of larger and larger denomination. The concept that this tsunami of paper money might be the cause of the “depreciation of the mark” both at home and abroad, never seemed to enter the minds of the masters of the printing presses. It's not like this hadn't happened before. All of the sequelæ of monetary inflation have been well documented over forty centuries of human history, from coin clipping and debasement in antiquity through the demise of every single unbacked paper currency ever created. Lord D'Abernon, the British ambassador in Berlin and British consular staff in cities across Germany precisely diagnosed the cause of the inflation and reported upon it in detail in their dispatches to the Foreign Office, but their attempts to explain these fundamentals to German officials were in vain. The Germans did not even need to look back in history at episodes such as the assignat hyperinflation in revolutionary France: just across the border in Austria, a near-identical hyperinflation had erupted just a few years earlier, and had eventually been stabilised in a manner similar to that eventually employed in Germany. The final stages of inflation induce a state resembling delirium, where people seek to exchange paper money for anything at all which might keep its value even momentarily, farmers with abundant harvests withhold them from the market rather than exchange them for worthless paper, foreigners bearing sound currency descend upon the country and buy up everything for sale at absurdly low prices, employers and towns, unable to obtain currency to pay their workers, print their own scrip, further accelerating the inflation, and the professional and middle classes are reduced to penury or liquidated entirely, while the wealthy, industrialists, and unionised workers do reasonably well by comparison. One of the principal problems in coping with inflation, whether as a policy maker or a citizen or business owner attempting to survive it, is inherent in its exponential growth. At any moment along the path, the situation is perceived as a “crisis” and the current circumstances “unsustainable”. But an exponential curve is self-similar: when you're living through one, however absurd the present situation may appear to be based on recent experience, it can continue to get exponentially more bizarre in the future by the inexorable continuation of the dynamic driving the curve. Since human beings have evolved to cope with mostly linear processes, we are ill-adapted to deal with exponential growth in anything. For example, we run out of adjectives: after you've used up “crisis”, “disaster”, “calamity”, “catastrophe”, “collapse”, “crash”, “debacle”, “ruin”, “cataclysm”, “fiasco”, and a few more, what do you call it the next time they tack on three more digits to all the money? This very phenomenon makes it difficult to bring inflation to an end before it completely undoes the social fabric. The longer inflation persists, the more painful wringing it out of an economy will be, and consequently the greater the temptation to simply continue to endure the ruinous exponential. Throughout the period of hyperinflation in Germany, the fragile government was painfully aware that any attempt to stabilise the currency would result in severe unemployment, which radical parties of both the Left and Right were poised to exploit. In fact, the hyperinflation was ended only by the elected government essentially ceding its powers to an authoritarian dictatorship empowered to put down social unrest as the costs of its policies were felt. At the time the stabilisation policies were put into effect in November 1923, the mark was quoted at six trillion to the British pound, and the paper marks printed and awaiting distribution to banks filled 300 ten-ton railway boxcars. What lessons does this remote historical episode have for us today? A great many, it seems to me. First and foremost, when you hear pundits holding forth about the Weimar inflation, it's valuable to know that much of what they're talking about is folklore and conventional wisdom which has little to do with events as they actually happened. Second, this chronicle serves to remind the reader of the one simple fact about inflation that politicians, bankers, collectivist media, organised labour, and rent-seeking crony capitalists deploy an entire demagogic vocabulary to conceal: that inflation is caused by an increase in the money supply, not by “greed”, “shortages”, “speculation”, or any of the other scapegoats trotted out to divert attention from where blame really lies: governments and their subservient central banks printing money (or, in current euphemism, “quantitative easing”) to stealthily default upon their obligations to creditors. Third, wherever and whenever inflation occurs, its ultimate effect is the destruction of the middle class, which has neither the political power of organised labour nor the connections and financial resources of the wealthy. Since liberal democracy is, in essence, rule by the middle class, its destruction is the precursor to establishment of authoritarian rule, which will be welcomed after the once-prosperous and self-reliant bourgeoisie has been expropriated by inflation and reduced to dependence upon the state. The Weimar inflation did not bring Hitler to power—for one thing the dates just don't work. The inflation came to an end in 1923, the year Hitler's beer hall putsch in Munich failed ignominiously and resulted in his imprisonment. The stabilisation of the economy in the following years was widely considered the death knell for radical parties on both the Left and Right, including Hitler's. It was not until the onset of the Great Depression following the 1929 crash that rising unemployment, falling wages, and a collapsing industrial economy as world trade contracted provided an opening for Hitler, and he did not become chancellor until 1933, almost a decade after the inflation ended. And yet, while there was no direct causal connection between the inflation and Hitler's coming to power, the erosion of civil society and the rule of law, the destruction of the middle class, and the lingering effects of the blame for these events being placed on “speculators” all set the stage for the eventual Nazi takeover. The technology and complexity of financial markets have come a long way from “Railway Rudy” Havenstein and his 300 boxcars of banknotes to “Helicopter Ben” Bernanke. While it used to take years of incompetence and mismanagement, leveling of vast forests, and acres of steam powered printing presses to destroy an industrial and commercial republic and impoverish those who sustain its polity, today a mere fat-finger on a keyboard will suffice. And yet the dynamic of inflation, once unleashed, proceeds on its own timetable, often taking longer than expected to corrode the institutions of an economy, and with ups and downs which tempt investors back into the market right before the next sickening slide. The endpoint is always the same: destruction of the middle class and pensioners who have provided for themselves and the creation of a dependent class of serfs at the mercy of an authoritarian regime. In past inflations, including the one documented in this book, this was an unintended consequence of ill-advised monetary policy. I suspect the crowd presently running things views this as a feature, not a bug. A Kindle edition is available, in which the table of contents and notes are properly linked to the text, but the index is simply a list of terms, not linked to their occurrences in the text. - Galt, John [pseud.]. The Day the Dollar Died. Florida: Self-published, 2011.

- I have often remarked in this venue how fragile the infrastructure of the developed world is, and how what might seem to be a small disruption could cascade into a black swan event which could potentially result in the end of the world as we know it. It is not only physical events such as EMP attacks, cyber attacks on critical infrastructure, or natural disasters such as hurricanes and earthquakes which can set off the downspiral, but also loss of confidence in the financial system in which all of the myriad transactions which make up the global division of labour on which our contemporary society depends. In a fiat money system, where currency has no intrinsic value and is accepted only on the confidence that it will be subsequently redeemable for other goods without massive depreciation, loss of that confidence can bring the system down almost overnight, and this has happened again and again in the sorry millennia-long history of paper money. As economist Herbert Stein observed, “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop”. But, when pondering the many “unsustainable” trends we see all around us today, it's important to bear in mind that they can often go on for much longer, diverging more into the world of weird than you ever imagined before stopping, and that when they finally do stop the débâcle can be more sudden and breathtaking in its consequences than even excitable forecasters conceived. In this gripping thriller, the author envisions the sudden loss in confidence of the purchasing power of the U.S. dollar and the ability of the U.S. government to make good on its obligations catalysing a meltdown of the international financial system and triggering dire consequences within the United States as an administration which believes “you never want a serious crisis to go to waste” exploits the calamity to begin “fundamentally transforming the United States of America”. The story is told in a curious way: by one first-person narrator and from the viewpoint of other people around the country recounted in third-person omniscient style. This is unusual, but I didn't find it jarring, and the story works. The recounting of the aftermath of sudden economic collapse is compelling, and will probably make you rethink your own preparations for such a dire (yet, I believe, increasingly probable) event. The whole post-collapse scenario is a little too black helicopter for my taste: we're asked to simultaneously believe that a government which has bungled its way into an apocalyptic collapse of the international economic system (entirely plausible in my view) will be ruthlessly efficient in imposing its new order (nonsense—it will be as mindlessly incompetent as in everything else it attempts). But the picture painted of how citizens can be intimidated or co-opted into becoming collaborators rings true, and will give you pause as you think about your friends and neighbours as potential snitches working for the Man. I found it particularly delightful that the author envisions a concept similar to my 1994 dystopian piece, Unicard, as playing a part in the story. At present, this book is available only in PDF format. I read it with Stanza on my iPad, which provides a reading experience equivalent to the Kindle and iBooks applications. The author says other electronic editions of this book will be forthcoming in the near future; when they're released they should be linked to the page cited above. The PDF edition is perfectly readable, however, so if this book interests you, there's no reason to wait. And, hey, it's free! As a self-published work, it's not surprising there are a number of typographical errors, although very few factual errors I noticed. That said, I've read novels published by major houses with substantially more copy editing goofs, and the errors here never confuse the reader nor get in the way of the narrative. For the author's other writings and audio podcasts, visit his Web site.

- Gilder, George. The Scandal of Money. Washington: Regnery Publishing, 2016. ISBN 978-1-62157-575-7.

-

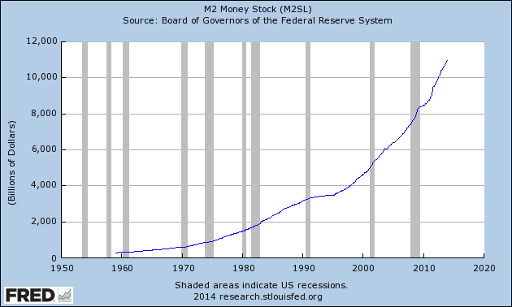

There is something seriously wrong with the global economy and the

financial system upon which it is founded. The nature of the

problem may not be apparent to the average person (and indeed, many

so-called “experts” fail to grasp what is going on), but

the symptoms are obvious. Real (after inflation) income for the

majority of working people has stagnated for decades. The economy

is built upon a pyramid of debt: sovereign (government), corporate,

and personal, which nobody really believes is ever going to be

repaid. The young, who once worked their way through college in

entry-level jobs, now graduate with crushing student debts which

amount to indentured servitude for the most productive years of

their lives. Financial markets, once a place where productive

enterprises could raise capital for their businesses by selling

shares in the company or interest-bearing debt, now seem to have

become a vast global casino, where gambling on the relative

values of paper money issued by various countries dwarfs genuine

economic activity: in 2013, the Bank for International Settlements

estimated these “foreign exchange” transactions to be

around US$ 5.3 trillion per day, more than a third of U.S.

annual Gross Domestic Product every twenty-four hours. Unlike a

legitimate casino where gamblers must make good on their losses,

the big banks engaged in this game have been declared “too

big to fail”, with taxpayers' pockets picked when they

suffer a big loss. If, despite stagnant earnings, rising prices,

and confiscatory taxes, an individual or family manages to set

some money aside, they find that the return from depositing it in

a bank or placing it in a low-risk investment is less than the

real rate of inflation, rendering saving a sucker's bet because

interest rates have been artificially repressed by central banks

to allow them to service the mountain of debt they are carrying.

It is easy to understand why the millions of ordinary people on

the short end of this deal have come to believe “the system is

rigged” and that “the rich are ripping us off”,

and listen attentively to demagogues confirming these observations,

even if the solutions they advocate are nostrums which have failed

every time and place they have been tried.

What, then, is wrong? George Gilder, author of the classic

Wealth and Poverty, the

supply side

Bible of the Reagan years, argues that what all of the dysfunctional

aspects of the economy have in common is money, and

that since 1971 we have been using a flawed definition of money

which has led to all of the pathologies we observe today. We

have come to denominate money in dollars, euros, yen, or other

currencies which mean only what the central banks that issue

them claim they mean, and whose relative value is set by

trading in the foreign exchange markets and can fluctuate on

a second-by-second basis. The author argues that the proper

definition of money is as a unit of time: the time

required for technological innovation and productivity

increases to create real wealth. This wealth (or value) comes from

information or knowledge. In chapter 1, he writes:

In an information economy, growth springs not from power but from knowledge. Crucial to the growth of knowledge is learning, conducted across an economy through the falsifiable testing of entrepreneurial ideas in companies that can fail. The economy is a test and measurement system, and it requires reliable learning guided by an accurate meter of monetary value.

Money, then, is the means by which information is transmitted within the economy. It allows comparing the value of completely disparate things: for example the services of a neurosurgeon and a ton of pork bellies, even though it is implausible anybody has ever bartered one for the other. When money is stable (its supply is fixed or grows at a constant rate which is small compared to the existing money supply), it is possible for participants in the economy to evaluate various goods and services on offer and, more importantly, make long term plans to create new goods and services which will improve productivity. When money is manipulated by governments and their central banks, such planning becomes, in part, a speculation on the value of currency in the future. It's like you were operating a textile factory and sold your products by the metre, and every morning you had to pick up the Wall Street Journal to see how long a metre was today. Should you invest in a new weaving machine? Who knows how long the metre will be by the time it's installed and producing? I'll illustrate the information theory of value in the following way. Compare the price of the pile of raw materials used in making a BMW (iron, copper, glass, aluminium, plastic, leather, etc.) with the finished automobile. The difference in price is the information embodied in the finished product—not just the transformation of the raw materials into the car, but the knowledge gained over the decades which contributed to that transformation and the features of the car which make it attractive to the customer. Now take that BMW and crash it into a bridge abutment on the autobahn at 200 km/h. How much is it worth now? Probably less than the raw materials (since it's harder to extract them from a jumbled-up wreck). Every atom which existed before the wreck is still there. What has been lost is the information (what electrical engineers call the “magic smoke”) which organised them into something people valued. When the value of money is unpredictable, any investment is in part speculative, and it is inevitable that the most lucrative speculations will be those in money itself. This diverts investment from improving productivity into financial speculation on foreign exchange rates, interest rates, and financial derivatives based upon them: a completely unproductive zero-sum sector of the economy which didn't exist prior to the abandonment of fixed exchange rates in 1971. What happened in 1971? On August 15th of that year, President Richard Nixon unilaterally suspended the convertibility of the U.S. dollar into gold, setting into motion a process which would ultimately destroy the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates which had been created as a pillar of the world financial and trade system after World War II. Under Bretton Woods, the dollar was fixed to gold, with sovereign holders of dollar reserves (but not individuals) able to exchange dollars and gold in unlimited quantities at the fixed rate of US$ 35/troy ounce. Other currencies in the system maintained fixed exchange rates with the dollar, and were backed by reserves, which could be held in either dollars or gold. Fixed exchange rates promoted international trade by eliminating currency risk in cross-border transactions. For example, a German manufacturer could import raw materials priced in British pounds, incorporate them into machine tools assembled by workers paid in German marks, and export the tools to the United States, being paid in dollars, all without the risk that a fluctuation by one or more of these currencies against another would wipe out the profit from the transaction. The fixed rates imposed discipline on the central banks issuing currencies and the governments to whom they were responsible. Running large trade deficits or surpluses, or accumulating too much public debt was deterred because doing so could force a costly official change in the exchange rate of the currency against the dollar. Currencies could, in extreme circumstances, be devalued or revalued upward, but this was painful to the issuer and rare. With the collapse of Bretton Woods, no longer was there a link to gold, either direct or indirect through the dollar. Instead, the relative values of currencies against one another were set purely by the market: what traders were willing to pay to buy one with another. This pushed the currency risk back onto anybody engaged in international trade, and forced them to “hedge” the currency risk (by foreign exchange transactions with the big banks) or else bear the risk themselves. None of this contributed in any way to productivity, although it generated revenue for the banks engaged in the game. At the time, the idea of freely floating currencies, with their exchange rates set by the marketplace, seemed like a free market alternative to the top-down government-imposed system of fixed exchange rates it supplanted, and it was supported by champions of free enterprise such as Milton Friedman. The author contends that, based upon almost half a century of experience with floating currencies and the consequent chaotic changes in exchange rates, bouts of inflation and deflation, monetary induced recessions, asset bubbles and crashes, and interest rates on low-risk investments which ranged from 20% to less than zero, this was one occasion Prof. Friedman got it wrong. Like the ever-changing metre in the fable of the textile factory, incessantly varying money makes long term planning difficult to impossible and sends the wrong signals to investors and businesses. In particular, when interest rates are forced to near zero, productive investment which creates new assets at a rate greater than the interest rate on the borrowed funds is neglected in favour of bidding up the price of existing assets, creating bubbles like those in real estate and stocks in recent memory. Further, since free money will not be allocated by the market, those who receive it are the privileged or connected who are first in line; this contributes to the justified perception of inequality in the financial system. Having judged the system of paper money with floating exchange rates a failure, Gilder does not advocate a return to either the classical gold standard of the 19th century or the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates with a dollar pegged to gold. Preferring to rely upon the innovation of entrepreneurs and the selection of the free market, he urges governments to remove all impediments to the introduction of multiple, competitive currencies. In particular, the capital gains tax would be abolished for purchases and sales regardless of the currency used. (For example, today you can obtain a credit card denominated in euros and use it freely in the U.S. to make purchases in dollars. Every time you use the card, the dollar amount is converted to euros and added to the balance on your bill. But, strictly speaking, you have sold euros and bought dollars, so you must report the transaction and any gain or loss from change in the dollar value of the euros in your account and the value of the ones you spent. This is so cumbersome it's a powerful deterrent to using any currency other than dollars in the U.S. Many people ignore the requirement to report such transactions, but they're breaking the law by doing so.) With multiple currencies and no tax or transaction reporting requirements, all will be free to compete in the market, where we can expect the best solutions to prevail. Using whichever currency you wish will be as seamless as buying something with a debit or credit card denominated in a currency different than the one of the seller. Existing card payment systems have a transaction cost which is so high they are impractical for “micropayment” on the Internet or for fully replacing cash in everyday transactions. Gilder suggests that Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies based on blockchain technology will probably be the means by which a successful currency backed 100% with physical gold or another hard asset will be used in transactions. This is a thoughtful examination of the problems of the contemporary financial system from a perspective you'll rarely encounter in the legacy financial media. The root cause of our money problems is the money: we have allowed governments to inflict upon us a monopoly of government-managed money, which, unsurprisingly, works about as well as anything else provided by a government monopoly. Our experience with this flawed system over more than four decades makes its shortcomings apparent, once you cease accepting the heavy price we pay for them as the normal state of affairs and inevitable. As with any other monopoly, all that's needed is to break the monopoly and free the market to choose which, among a variety of competing forms of money, best meet the needs of those who use them. Here is a Bookmonger interview with the author discussing the book. - Gladwell, Malcolm. The Tipping Point. Boston: Little, Brown, 2000. ISBN 0-316-31696-2.

- Griffin, G. Edward. The Creature from Jekyll Island. Westlake Village, CA: American Media, [1994, 1995, 1998, 2002] 2010. ISBN 978-0-912986-45-6.

-

Almost every time I review a book about or discuss the U.S.

Federal Reserve System in a conversation or Internet post,

somebody recommends this book. I'd never gotten around to

reading it until recently, when a couple more mentions of it

pushed me over the edge. And what an edge that turned out

to be. I cannot recommend this book to anybody; there are

far more coherent, focussed, and persuasive analyses of

the Federal Reserve in print, for example Ron Paul's excellent

book End the Fed (October 2009).

The present book goes well beyond a discussion of the Federal

Reserve and rambles over millennia of history in a chaotic

manner prone to induce temporal vertigo in the reader, discussing

the history of money, banking, political manipulation of

currency, inflation, fractional reserve banking, fiat

money, central banking, cartels, war profiteering,

bailouts, monetary panics and bailouts, nonperforming loans

to “developing” nations, the Rothschilds and

Rockefellers, booms and busts, and more.

The author is inordinately fond of conspiracy theories. As

we pursue our random walk through history and around the

world, we encounter:

- The sinking of the Lusitania

- The assassination of Abraham Lincoln

- The Order of the Knights of the Golden Circle, the Masons, and the Ku Klux Klan

- The Bavarian Illuminati

- Russian Navy intervention in the American Civil War

- Cecil Rhodes and the Round Table Groups

- The Council on Foreign Relations

- The Fabian Society

- The assassination of John F. Kennedy

- Theodore Roosevelt's “Bull Moose” run for the U.S. presidency in 1912

- The Report from Iron Mountain

- The attempted assassination of Andrew Jackson in 1835

- The Bolshevik Revolution in Russia

- Hayek, Friedrich A. The Road to Serfdom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, [1944] 1994. ISBN 0-226-32061-8.

- Hayek, Friedrich A. The Fatal Conceit. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988. ISBN 0-226-32066-9.

- The idiosyncratic, if not downright eccentric, synthesis of evolutionary epistemology, spontaneous emergence of order in self-organising systems, free markets as a communication channel and feedback mechanism, and individual liberty within a non-coercive web of cultural traditions which informs my scribblings here and elsewhere is the product of several decades of pondering these matters, digesting dozens of books by almost as many authors, and discussions with brilliant and original thinkers it has been my privilege to encounter over the years. If, however, you want it all now, here it is, in less than 160 pages of the pellucid reasoning and prose for which Hayek is famed, ready to be flashed into your brain's philosophical firmware in a few hours' pleasant reading. This book sat on my shelf for more than a decade before I picked it up a couple of days ago and devoured it, exclaiming “Yes!”, “Bingo!”, and “Precisely!” every few pages. The book is subtitled “The Errors of Socialism”, which I believe both misstates and unnecessarily restricts the scope of the actual content, for the errors of socialism are shared by a multitude of other rationalistic doctrines (including the cult of design in software development) which, either conceived before biological evolution was understood, or by those who didn't understand evolution or preferred the outlook of Aristotle and Plato for aesthetic reasons (“evolution is so messy, and there's no rational plan to it”), assume, as those before Darwin and those who reject his discoveries today, that the presence of apparent purpose implies the action of rational design. Hayek argues (and to my mind demonstrates) that the extended order of human interaction: ethics, morality, division of labour, trade, markets, diffusion of information, and a multitude of other components of civilisation fall between biological instinct and reason, poles which many philosophers consider a dichotomy. This middle ground, the foundation of civilisation, is the product of cultural evolution, in which reason plays a part only in variation, and selection occurs just as brutally and effectively as in biological evolution. (Cultural and biological evolution are not identical, of course; in particular, the inheritance of acquired traits is central in the development of cultures, yet absent in biology.) The “Fatal Conceit” of the title is the belief among intellectuals and social engineers, mistaking the traditions and institutions of human civilisation for products of reason instead of evolution, that they can themselves design, on a clean sheet of paper as it were, a one-size-fits-all eternal replacement which will work better than the product of an ongoing evolutionary process involving billions of individuals over millennia, exploring a myriad of alternatives to find what works best. The failure to grasp the limits of reason compared to evolution explains why the perfectly consistent and often tragic failures of utopian top-down schemes never deters intellectuals from championing new (or often old, already discredited) ones. Did I say I liked this book?

- Hazlitt, Henry. Economics in One Lesson. New York: Three Rivers Press, [1946, 1962] 1979. ISBN 0-517-54823-2.

- Kauffman, Stuart A. Investigations. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-19-512105-8.

-

Few people have thought as long and as hard about the origin

of life and the emergence of complexity in a biosphere as

Stuart Kauffman. Medical doctor, geneticist, professor of

biochemistry and biophysics, MacArthur Fellow, and member of

the faculty of the Santa Fe Institute for a decade, he has

sought to discover the principles which might underlie

a “general biology”—the laws which

would govern any biosphere, whether terrestrial, extraterrestrial, or

simulated within a computer, regardless of its physical

substrate.

This book, which he describes on occasion as “protoscience”,

provides an overview of the principles he suspects, but cannot

prove, may underlie all forms of life, and beyond that systems

in general which are far from equilibrium such as a modern

technological economy and the universe itself. Most of science

before the middle of the twentieth century studied complex

systems at or near equilibrium; only at such states could the

simplifying assumptions of statistical mechanics be applied to

render the problem tractable. With computers, however, we can now

begin to explore open systems (albeit far smaller than those in nature)

which are far from equilibrium, have dynamic flows of energy and

material, and do not necessarily evolve toward a state of maximum

entropy.

Kauffman believes there may be what amounts to a fourth law of

thermodynamics which applies to such systems and, although we don't

know enough to state it precisely, he suspects it may be that these

open, extremely nonergodic, systems evolve as rapidly as possible to

expand and fill their state space and that unlike, say, a gas in a

closed volume or the stars in a galaxy, where the complete state space

can be specified in advance (that is, the dimensionality of the space,

not the precise position and momentum values of every object within

it), the state space of a non-equilibrium system cannot be prestated

because its very evolution expands the state space. The presence of

autonomous agents introduces another level of complexity and

creativity, as evolution drives the agents to greater and greater

diversity and complexity to better adapt to the ever-shifting fitness

landscape.

These are complicated and deep issues, and this is a very difficult

book, although appearing, at first glance, to be written for a popular

audience. I seriously doubt whether somebody who was not previously

acquainted with these topics and thought about them at some length

will make it to the end and, even if they do, take much away from the

book. Those who are comfortable with the laws of thermodynamics,

the genetic code, protein chemistry, catalysis, autocatalytic

networks, Carnot cycles, fitness landscapes, hill-climbing strategies,

the no-go theorem, error catastrophes, self-organisation, percolation

phase transitions in graphs, and other technical issues raised in the

arguments must still confront the author's prose style. It seems

like Kauffman aspires to be a prose stylist conveying a sense of

wonder to his readers along the lines of Carl Sagan and

Stephen Jay Gould. Unfortunately, he doesn't pull it off as well,

and the reader must wade through numerous paragraphs like the following

from pp. 97–98:

Does it always take work to construct constraints? No, as we will soon see. Does it often take work to construct constraints? Yes. In those cases, the work done to construct constraints is, in fact, another coupling of spontaneous and nonspontaneous processes. But this is just what we are suggesting must occur in autonomous agents. In the universe as a whole, exploding from the big bang into this vast diversity, are many of the constraints on the release of energy that have formed due to a linking of spontaneous and nonspontaneous processes? Yes. What might this be about? I'll say it again. The universe is full of sources of energy. Nonequilibrium processes and structures of increasing diversity and complexity arise that constitute sources of energy that measure, detect, and capture those sources of energy, build new structures that constitute constraints on the release of energy, and hence drive nonspontaneous processes to create more such diversifying and novel processes, structures, and energy sources.

I have not cherry-picked this passage; there are hundreds of others like it. Given the complexity of the technical material and the difficulty of the concepts being explained, it seems to me that the straightforward, unaffected Point A to Point B style of explanation which Isaac Asimov employed would work much better. Pardon my audacity, but allow me to rewrite the above paragraph.Autonomous agents require energy, and the universe is full of sources of energy. But in order to do work, they require energy to be released under constraints. Some constraints are natural, but others are constructed by autonomous agents which must do work to build novel constraints. A new constraint, once built, provides access to new sources of energy, which can be exploited by new agents, contributing to an ever growing diversity and complexity of agents, constraints, and sources of energy.

Which is better? I rewrite; you decide. The tone of the prose is all over the place. In one paragraph he's talking about Tomasina the trilobite (p. 129) and Gertrude the ugly squirrel (p. 131), then the next thing you know it's “Here, the hexamer is simplified to 3'CCCGGG5', and the two complementary trimers are 5'GGG3' + 5'CCC3'. Left to its own devices, this reaction is exergonic and, in the presence of excess trimers compared to the equilibrium ratio of hexamer to trimers, will flow exergonically toward equilibrium by synthesizing the hexamer.” (p. 64). This flipping back and forth between colloquial and scholarly voices leads to a kind of comprehensional kinetosis. There are a few typographical errors, none serious, but I have to share this delightful one-sentence paragraph from p. 254 (ellipsis in the original):By iteration, we can construct a graph connecting the founder spin network with its 1-Pachner move “descendants,” 2-Pachner move descendints…N-Pachner move descendents.

Good grief—is Oxford University Press outsourcing their copy editing to Slashdot? For the reasons given above, I found this a difficult read. But it is an important book, bristling with ideas which will get you looking at the big questions in a different way, and speculating, along with the author, that there may be some profound scientific insights which science has overlooked to date sitting right before our eyes—in the biosphere, the economy, and this fantastically complicated universe which seems to have emerged somehow from a near-thermalised big bang. While Kauffman is the first to admit that these are hypotheses and speculations, not science, they are eminently testable by straightforward scientific investigation, and there is every reason to believe that if there are, indeed, general laws that govern these phenomena, we will begin to glimpse them in the next few decades. If you're interested in these matters, this is a book you shouldn't miss, but be aware what you're getting into when you undertake to read it. - Leeson, Peter T. The Invisible Hook. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-691-13747-6.

-

(Guest review by

Iron Jack Rackham)