- Faulks, Sebastian.

Jeeves and the Wedding Bells.

London: Hutchinson, 2013.

ISBN 978-0-09-195404-8.

-

As a fan of P. G. Wodehouse

ever since I started reading his work in the 1970s, and having read every

single Jeeves

and Wooster

story, it was with some trepidation that I picked up this novel,

the first Jeeves and Wooster story since

Aunts

Aren't Gentlemen, published in 1974, a year before Wodehouse's

death. This book, published with the permission of the Wodehouse estate,

is described by the author as a tribute to P. G. Wodehouse which he hopes

will encourage readers to discover the work of the master.

The author notes that, while remaining true to the characters of Jeeves

and Wooster and the ambience of the stories, he did not attempt to mimic

Wodehouse's style. Notwithstanding, to this reader, the result is so close

to that of Wodehouse that if you dropped it into a Wodehouse collection

unlabelled, I suspect few readers would find anything discordant.

Faulks's Jeeves seems to use more jaw-breaking words than I recall

Wodehouse's, but that's about it. Apart from Jeeves and Wooster, none of the

regular characters who populate Wodehouse's stories appear on stage here.

We hear of members of the

Drones, the terrifying

Aunt Agatha, and

others, and mentions of previous episodes involving them, but all of the

other dramatis personæ are new.

On holiday in the south of France, Bertie Wooster makes the acquaintance

of Georgiana Meadowes, a copy editor for a London publisher having escaped

the metropolis to finish marking up a manuscript. Bertie is immediately

smitten, being impressed by Georgiana's beauty, brains, and wit, albeit

less so with her driving (“To say she drove in the French fashion would

be to cast a slur on those fine people.”). Upon his return to London,

Bertie soon reads that Georgiana has become engaged to a travel writer she

mentioned her family urging her to marry. Meanwhile, one of Bertie's

best friends, “Woody” Beeching, confides his own problem with

the fairer sex. His fiancée has broken off the engagement because

her parents, the Hackwoods, need their daughter to marry into wealth to save

the family seat, at risk of being sold. Before long, Bertie discovers that

the matrimonial plans of Georgiana and Woody are linked in a subtle but

inflexible way, and that a delicate hand, acting with nuance, will be

needed to assure all ends well.

Evidently, a job crying out for the attention of Bertram Wilberforce Wooster!

Into the fray Jeeves and Wooster go, and before long a quintessentially

Wodehousean series of impostures, misadventures, misdirections, eccentric

characters, disasters at the dinner table, and carefully crafted stratagems

gone horribly awry ensue. If you are not acquainted with that

game

which the English, not being a very spiritual people, invented to

give them some idea of eternity

(G. B. Shaw), you may want to review the rules before reading chapter 7.

Doubtless some Wodehouse fans will consider any author's bringing Jeeves

and Wooster back to life a sacrilege, but this fan simply relished the

opportunity to meet them again in a new adventure which is entirely

consistent with the Wodehouse canon and characters. I would have been

dismayed had this been a parody or some “transgressive” despoilation

of the innocent world these characters inhabit. Instead we have a

thoroughly enjoyable romp in which the prodigious brain of Jeeves once

again saves the day.

The U.K. edition is linked above.

U.S. and worldwide Kindle editions

are available.

- Pooley, Charles and Ed LeBouthillier.

Microlaunchers.

Seattle: CreateSpace, 2013.

ISBN 978-1-4912-8111-6.

-

Many fields of engineering are subject to scaling laws: as you make

something bigger or smaller various trade-offs occur, and the properties

of materials, cost, or other design constraints set limits on the

largest and smallest practical designs. Rockets for launching payloads

into Earth orbit and beyond tend to scale well as you increase their

size. Because of the

cube-square law,

the volume of propellant a tank holds increases as the cube of the

size while the weight of the tank goes as the square (actually a bit

faster since a larger tank will require more robust walls, but for a

rough approximation calling it the square will do). Viable rockets

can get very big indeed: the

Sea Dragon,

although never built, is considered a workable design. With a length of

150 metres and 23 metres in diameter, it would have more than ten times the

first stage thrust of a Saturn V and place 550 metric tons into low Earth

orbit.

What about the other end of the scale? How small could a space

launcher be, what technologies might be used in it, and what

would it cost? Would it be possible to scale a launcher down so

that small groups of individuals, from hobbyists to college class

projects, could launch their own spacecraft? These are the questions

explored in this fascinating and technically thorough book. Little

practical work has been done to explore these questions. The smallest

launcher to place a satellite in orbit was the Japanese

Lambda 4S

with a mass of 9400 kg and length of 16.5 metres. The U.S.

Vanguard

rocket had a mass of 10,050 kg and length of 23 metres. These are,

though small compared to the workhorse launchers of today, still

big, heavy machines, far beyond the capabilities of small groups of

people, and sufficiently dangerous if something goes wrong that they

require launch sites in unpopulated regions.

The scale of launchers has traditionally been driven by the mass

of the payload they carry to space. Early launchers carried satellites

with crude 1950s electronics, while many of their successors were

derived from ballistic missiles sized to deliver heavy nuclear warheads.

But today,

CubeSats have

demonstrated that useful work can be done by spacecraft with

a volume of one litre and mass of 1.33 kg or less, and the

PhoneSat

project holds out the hope of functional spacecraft comparable

in weight to a mobile telephone. While to date these small satellites

have flown as piggy-back payloads on other launches, the availability

of dedicated launchers sized for them would increase the number of

launch opportunities and provide access to trajectories unavailable

in piggy-back opportunities.

Just because launchers have tended to grow over time doesn't mean

that's the only way to go. In the 1950s and '60s many people

expected computers to continue their trend of getting bigger and

bigger to the point where there were a limited number of

“computer utilities” with vast machines which

customers accessed over the telecommunication network. But then came

the minicomputer and microcomputer revolutions and today the

computing power in personal computers and mobile devices dwarfs that

of all supercomputers combined. What would it take technologically

to spark a similar revolution in space launchers?

With the smallest successful launchers to date having a mass of around

10 tonnes, the authors choose two weight budgets: 1000 kg on the

high end and 100 kg as the low. They divide these budgets

into allocations for payload, tankage, engines, fuel, etc. based

upon the experience of existing sounding rockets, then explore what

technologies exist which might enable such a vehicle to achieve

orbital or escape velocity. The 100 kg launcher is a huge technological

leap from anything with which we have experience and probably could be

built, if at all, only after having gained experience from earlier

generations of light launchers. But then the current state of the art

in microchip fabrication would have seemed like science fiction to

researchers in the early days of integrated circuits and it took

decades of experience and generation after generation of chips and

many technological innovations to arrive where we are today. Consequently,

most of the book focuses on a three stage launcher with the 1000 kg mass

budget, capable of placing a payload of between 150 and 200 grams on

an Earth escape trajectory.

The book does not spare the rigour. The reader is introduced to the

rocket equation,

formulæ for aerodynamic drag, the

standard

atmosphere, optimisation of mixture ratios, combustion chamber

pressure and size, nozzle expansion ratios, and a multitude of

other details which make the difference between success and failure.

Scaling to the size envisioned here without expensive and exotic

materials and technologies requires out of the box thinking, and

there is plenty on display here, including using beverage cans for

upper stage propellant tanks.

A 1000 kg space launcher appears to be entirely feasible. The

question is whether it can be done without the budget of hundreds

of millions of dollars and years of development it would certainly

take were the problem assigned to an aerospace prime contractor.

The authors hold out the hope that it can be done, and observe that

hobbyists and small groups can begin working independently on components:

engines, tank systems, guidance and navigation, and so on, and then

share their work precisely as open source software developers do so

successfully today.

This is a field where prizes may work very well to encourage

development of the required technologies. A philanthropist

might offer, say, a prize of a million dollars for launching a

150 gram communicating payload onto an Earth escape trajectory,

and a series of smaller prizes for engines which met the

requirements for the various stages, flight-weight tankage and

stage structures, etc. That way teams with expertise in various

areas could work toward the individual prizes without having to

take on the all-up integration required for the complete vehicle.

This is a well-researched and hopeful look at a technological

direction few have thought about. The book is well written and

includes all of the equations and data an aspiring rocket engineer

will need to get started. The text is marred by a number of

typographical errors (I counted two dozen) but only one trivial

factual error. Although other references are mentioned in the

text, a bibliography of works for those interested in exploring

further would be a valuable addition. There is no index.

- Crocker, George N.

Roosevelt's Road To Russia.

Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, [1959] 2010.

ISBN 978-1-163-82408-5.

-

Before Barack Obama, there was Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Unless you lived through the era, imbibed its history from

parents or grandparents, or have read dissenting works which

have survived rounds of deaccessions by libraries, it is hard

to grasp just how visceral the animus was against Roosevelt

by traditional, constitutional, and free-market conservatives.

Roosevelt seized control of the economy, extended the tentacles

of the state into all kinds of relations between individuals,

subdued the judiciary and bent it to his will, manipulated a

largely supine media which, with a few exceptions, became his

cheering section, and created programs which made large sectors

of the population directly dependent upon the federal government

and thus a reliable constituency for expanding its power.

He had the audacity to stand for re-election an unprecedented

three times, and each time the American people gave him the nod.

But, as many old-timers, even those who were opponents of

Roosevelt at the time and appalled by what the centralised

super-state he set into motion has become, grudgingly say,

“He won the war.” Well, yes, by the time he died

in office on April 12, 1945, Germany was close to defeat;

Japan was encircled, cut off from the resources needed to

continue the war, and being devastated by attacks from the air;

the war was sure to be won by the Allies. But how did the

U.S. find itself in the war in the first place, how did

Roosevelt's policies during the war affect its conduct, and

what consequences did they have for the post-war world?

These are the questions explored in this book, which I suppose

contemporary readers would term a “paleoconservative”

revisionist account of the epoch, published just 14 years after

the end of the war. The work is mainly an account of Roosevelt's

personal diplomacy during meetings with Churchill or in the

Big Three conferences with Churchill and Stalin. The picture

of Roosevelt which emerges is remarkably consistent with what

Churchill expressed in deepest confidence to those closest

to him which I summarised in my review of

The Last Lion, Vol. 3 (January 2013)

as “a lightweight, ill-informed and not particularly

engaged in military affairs and blind to the geopolitical

consequences of the Red Army's occupying eastern and central

Europe at war's end.” The events chronicled here and

Roosevelt's part in them is also very much the same as

described in

Freedom Betrayed (June 2012),

which former president Herbert Hoover worked on from shortly

after Pearl Harbor until his death in 1964, but which was not

published until 2011.

While Churchill was constrained in what he could say by the

necessity of maintaining Britain's alliance with the U.S., and

Hoover adopts a more scholarly tone, the present volume voices

the outrage over Roosevelt's strutting on the international

stage, thinking “personal diplomacy”

could “bring around ‘Uncle Joe’ ”,

condemning huge numbers of military personnel and civilians on

both the Allied and Axis sides to death by blurting out

“unconditional surrender” without any consultation

with his staff or Allies, approving the genocidal

Morgenthau Plan

to de-industrialise defeated Germany, and, discarding the

high principles of his own

Atlantic Charter,

delivering millions of Europeans into communist tyranny and

condoning one of the largest episodes of ethnic cleansing in

human history.

What is remarkable is how difficult it is to come across an

account of this period which evokes the author's passion,

shared with many of his time, of how the bumblings of a

naïve, incompetent, and narcissistic chief executive

had led directly to so much avoidable tragedy on a global

scale. Apart from Hoover's book, finally published more than

half a century after this account, there are few works accessible

to the general reader which present the view that the tragic outcome

of World War II was in large part preventable, and that Roosevelt

and his advisers were responsible, in large part, for what

happened.

Perhaps there are parallels in this account of wickedness

triumphing through cluelessness for our present era.

This edition is a facsimile reprint of the original edition

published by Henry Regnery Company in 1959.

- Turk, James and John Rubino.

The Money Bubble.

Unknown: DollarCollapse Press, 2013.

ISBN 978-1-62217-034-0.

-

It is famously difficult to perceive when you're living

through a financial bubble. Whenever a bubble is expanding,

regardless of its nature, people with a short time horizon,

particularly those riding the bubble without experience of

previous boom/bust cycles, not only assume it will continue

to expand forever, they will find no shortage of

financial gurus to assure them that what, to an outsider

appears a completely unsustainable aberration is, in fact,

“the new normal”.

It used to be that bubbles would occur only around once in

a human generation. This meant that those caught up in them

would be experiencing one for the first time and

discount the warnings of geezers who were fleeced the

last time around. But in our happening world the pace of things

accelerates, and in the last 20 years we have seen three

successive bubbles, each segueing directly into the next:

- The Internet/NASDAQ bubble

- The real estate bubble

- The bond market bubble

The last bubble is still underway, although the first cracks

in its expansion have begun to appear at this writing.

The authors argue that these serial bubbles are the consequence

of a grand underlying bubble which has been underway for decades:

the money bubble—the creation out of thin air of currency

by central banks, causing more and more money to chase whatever

assets happen to be in fashion at the moment, thus resulting in

bubble after bubble until the money bubble finally pops.

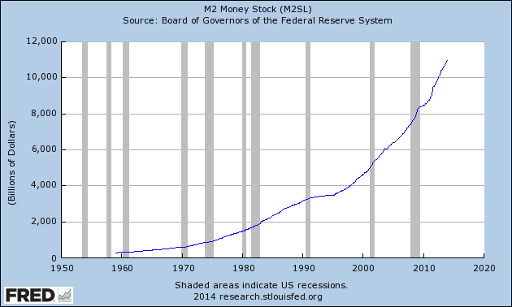

Although it can be psychologically difficult to diagnose a bubble

from the inside, if we step back to the abstract level of charts, it isn't

all that hard. Whenever you see an exponential curve climbing to

the sky, it's not only a safe bet but a sure thing that it won't

continue to do so forever. Now, it may go on much longer than you

might imagine: as

John Maynard Keynes

said, “Markets can

remain irrational a lot longer than you and I can remain

solvent”—but not forever. Let's look at a chart of

the M2 money stock (one of the measures of the supply of money

denominated in U.S. dollars) from 1959 through the end of 2013

(click the chart to see data updated through the present

date).

You will rarely see a more perfect exponential growth curve than this:

if you re-plot it on a semi-log axis, the fit to a straight line is

remarkable.

Ever since the creation of the Federal Reserve System in the United

States in 1913, and especially since the link between the U.S.

dollar and gold was severed in 1971, all of the world's principal

trading currencies have been

fiat money: paper

or book-entry money without any intrinsic value, created by a government

who enforces its use through

legal tender

laws. Since governments are the modern incarnation of the bands of

thieves and murderers who have afflicted humans ever since our

origin in Africa, it is to be expected that once such a band

obtains the power to create money which it can coerce its subjects

to use they will quickly abuse that power to loot their subjects

and enrich themselves, as least as long as they can keep the game

going. In the end, it is inevitable that people will wise up to the

scam, and that the paper money will be valuable only as scratchy

toilet paper. So it has been long before the advent of proper

toilet paper.

In this book the authors recount the sorry history of paper money

and debt-fuelled bubbles and examine possible scenarios as the

present unsustainable system inevitably comes to an end. It

is very difficult to forecast what will happen: we appear to be

heading for what

Ludwig von Mises

called a “crack-up boom”. This is where, as he wrote, “the

masses wake up”, and things go all nonlinear. The preconditions

for this are already in place, but there is no way to know when

it will dawn upon a substantial fraction of the population that

their savings have been looted, their retirement deferred until

death, their children indentured to a lifetime of debt, and their

nation destined to become a stratified society with a small fraction

of super-wealthy in their gated communities and a mass of impoverished

people, disarmed, dumbed down by design, and kept in line by

control of their means to communicate, travel, and organise. It is

difficult to make predictions beyond that point, as many disruptive things

can happen as a society approaches it. This is not an

environment in which one can make investment decisions as one

would have in the heady days of the 1950s.

And yet, one must—at least people who have managed to save for their

retirement and to provide their children a hand up in this

increasingly difficult world. The authors, drawing upon historical

parallels in previous money and debt bubbles, suggest what asset

classes to avoid, which are most likely to ride out the coming

turbulence and, for the adventure-seeking with some money left over

to take a flyer, a number of speculations which may perform well as

the money bubble pops. Remember that in a financial smash-up almost

everybody loses: it is difficult in a time of chaos, when assets

previously thought risk-free or safe are fluctuating wildly, just

to preserve your purchasing power. In such times those who

lose the least are the relative winners, and are in the

best position when emerging from the hard times to acquire assets

at bargain basement prices which will be the foundation of their

family fortune as the financial system is reconstituted upon a foundation

of sound money.

This book focusses on the history of money and debt bubbles, the

invariants from those experiences which can guide us as the

present madness ends, and provides guidelines for making the

most (or avoiding the worst) of what is to come. If you're looking

for “Untold Riches from the Coming Collapse”,

this isn't your book. These are very conservative recommendations

about what to do and what to avoid, and a few suggestions for

speculations, but the focus is on preservation of one's hard-earned

capital through what promises to be a very turbulent era.

In the Kindle edition the index cites page

numbers from the print edition which are useless since the Kindle

edition does not include page numbers.

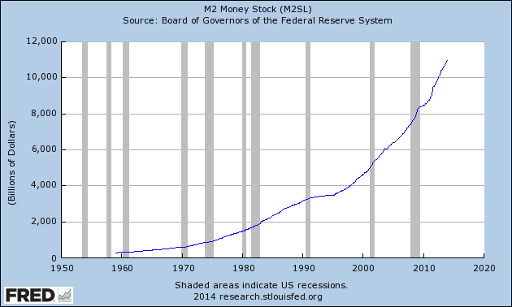

You will rarely see a more perfect exponential growth curve than this:

if you re-plot it on a semi-log axis, the fit to a straight line is

remarkable.

Ever since the creation of the Federal Reserve System in the United

States in 1913, and especially since the link between the U.S.

dollar and gold was severed in 1971, all of the world's principal

trading currencies have been

fiat money: paper

or book-entry money without any intrinsic value, created by a government

who enforces its use through

legal tender

laws. Since governments are the modern incarnation of the bands of

thieves and murderers who have afflicted humans ever since our

origin in Africa, it is to be expected that once such a band

obtains the power to create money which it can coerce its subjects

to use they will quickly abuse that power to loot their subjects

and enrich themselves, as least as long as they can keep the game

going. In the end, it is inevitable that people will wise up to the

scam, and that the paper money will be valuable only as scratchy

toilet paper. So it has been long before the advent of proper

toilet paper.

In this book the authors recount the sorry history of paper money

and debt-fuelled bubbles and examine possible scenarios as the

present unsustainable system inevitably comes to an end. It

is very difficult to forecast what will happen: we appear to be

heading for what

Ludwig von Mises

called a “crack-up boom”. This is where, as he wrote, “the

masses wake up”, and things go all nonlinear. The preconditions

for this are already in place, but there is no way to know when

it will dawn upon a substantial fraction of the population that

their savings have been looted, their retirement deferred until

death, their children indentured to a lifetime of debt, and their

nation destined to become a stratified society with a small fraction

of super-wealthy in their gated communities and a mass of impoverished

people, disarmed, dumbed down by design, and kept in line by

control of their means to communicate, travel, and organise. It is

difficult to make predictions beyond that point, as many disruptive things

can happen as a society approaches it. This is not an

environment in which one can make investment decisions as one

would have in the heady days of the 1950s.

And yet, one must—at least people who have managed to save for their

retirement and to provide their children a hand up in this

increasingly difficult world. The authors, drawing upon historical

parallels in previous money and debt bubbles, suggest what asset

classes to avoid, which are most likely to ride out the coming

turbulence and, for the adventure-seeking with some money left over

to take a flyer, a number of speculations which may perform well as

the money bubble pops. Remember that in a financial smash-up almost

everybody loses: it is difficult in a time of chaos, when assets

previously thought risk-free or safe are fluctuating wildly, just

to preserve your purchasing power. In such times those who

lose the least are the relative winners, and are in the

best position when emerging from the hard times to acquire assets

at bargain basement prices which will be the foundation of their

family fortune as the financial system is reconstituted upon a foundation

of sound money.

This book focusses on the history of money and debt bubbles, the

invariants from those experiences which can guide us as the

present madness ends, and provides guidelines for making the

most (or avoiding the worst) of what is to come. If you're looking

for “Untold Riches from the Coming Collapse”,

this isn't your book. These are very conservative recommendations

about what to do and what to avoid, and a few suggestions for

speculations, but the focus is on preservation of one's hard-earned

capital through what promises to be a very turbulent era.

In the Kindle edition the index cites page

numbers from the print edition which are useless since the Kindle

edition does not include page numbers.