Computing

- Albrecht, Katherine and Liz McIntyre. Spychips. Nashville: Nelson Current, 2005. ISBN 0-452-28766-9.

-

Imagine a world in which every manufactured object, and even living

creatures such as pets, livestock, and eventually people, had an embedded tag

with a unique 96-bit code which uniquely identified it among all

macroscopic objects on the planet and beyond. Further, imagine that

these tiny, unobtrusive and non-invasive tags could be interrogated

remotely, at a distance of up to several metres, by safe radio

frequency queries which would provide power for them to transmit

their identity. What could you do with this? Well, a heck of a lot.

Imagine, for example, a refrigerator which sensed its entire contents, and

was able to automatically place an order on the Internet for home delivery

of whatever was running short, or warned you that the item you'd just

picked up had passed its expiration date. Or think about breezing

past the checkout counter at the Mall-Mart with a cart full of stuff without

even slowing down—all of the goods would be identified by the portal

at the door, and the total charged to the account designated by the

tag in your customer fidelity card. When you're shopping, you could be

automatically warned when you pick up a product which contains an

ingredient to which you or a member of your family is allergic. And if

a product is recalled, you'll be able to instantly determine whether

you have one of the affected items, if your refrigerator or smart

medicine cabinet hasn't already done so. The benefits just go on

and on…imagine.

This is the vision of an “Internet of Things”, in which all tangible

objects are, in a real sense, on-line in real-time, with their position and

status updated by ubiquitous and networked sensors. This is not a utopian

vision. In 1994 I sketched Unicard, a

unified personal identity document, and explored its consequences; people

laughed: “never happen”. But just five years later, the

Auto-ID Labs were formed at MIT, dedicated

to developing a far more ubiquitous identification technology. With the support

of major companies such as Procter & Gamble, Philip Morris, Wal-Mart,

Gillette, and IBM, and endorsement by organs of the United States government,

technology has been developed and commercialised to implement tagging

everything and tracking its every movement.

As I alluded to obliquely in Unicard, this has

its downsides. In particular, the utter and irrevocable loss of all forms of

privacy and anonymity. From the moment you enter a store, or your workplace, or

any public space, you are tracked. When you pick up a product, the amount of time

you look at it before placing it in your shopping cart or returning it to the

shelf is recorded (and don't even think about leaving the store without

paying for it and having it logged to your purchases!). Did you pick the

bargain product? Well, you'll soon be getting junk mail and electronic coupons on your mobile

phone promoting the premium alternative with a higher profit margin to the retailer.

Walk down the street, and any miscreant with a portable tag reader can

“frisk” you without your knowledge, determining the contents of your

wallet, purse, and shopping bag, and whether you're wearing a watch worth

snatching. And even when you discard a product, that's a public event: garbage

voyeurs can drive down the street and correlate what you throw out by the tags

of items in your trash and the tags on the trashbags they're in.

“But we don't intend to do any of that”, the proponents of

radio frequency identification

(RFID)

protest. And perhaps they don't, but if it is possible and the data

are collected, who knows what will be done with it in the future,

particularly by governments already installing surveillance cameras

everywhere. If they don't have the data, they can't abuse them; if they

do, they may; who do you trust with a complete record of everywhere you go,

and everything you buy, sell, own, wear, carry, and discard?

This book presents, in a form that non-specialists can understand, the

RFID-enabled future which manufacturers, retailers, marketers, academics,

and government are co-operating to foist upon their consumers, clients,

marks, coerced patrons, and subjects respectively. It is

not a pretty picture. Regrettably, this book could be much better than

it is. It's written in a kind of breathy muckraking rant style, with

numerous paragraphs like (p. 105):

Yes, you read that right, they plan to sell data on our trash. Of course. We should have known that BellSouth was just another megacorporation waiting in the wings to swoop down on the data revealed once its fellow corporate cronies spychip the world.

I mean, I agree entirely with the message of this book, having warned of modest steps in that direction eleven years before its publication, but prose like this makes me feel like I'm driving down the road in a 1964 Vance Packard getting all righteously indignant about things we'd be better advised to coldly and deliberately draw our plans against. This shouldn't be so difficult, in principle: polls show that once people grasp the potential invasion of privacy possible with RFID, between 2/3 and 3/4 oppose it. The problem is that it's being deployed via stealth, starting with bulk pallets in the supply chain and, once proven there, migrated down to the individual product level. Visibility is a precious thing, and one of the most insidious properties of RFID tags is their very invisibility. Is there a remotely-powered transponder sandwiched into the sole of your shoe, linked to the credit card number and identity you used to buy it, which “phones home” every time you walk near a sensor which activates it? Who knows? See how the paranoia sets in? But it isn't paranoia if they're really out to get you. And they are—for our own good, naturally, and for the children, as always. In the absence of a policy fix for this (and the extreme unlikelihood of any such being adopted given the natural alliance of business and the state in tracking every move of their customers/subjects), one extremely handy technical fix would be a broadband, perhaps software radio, which listened on the frequency bands used by RFID tag readers and snooped on the transmissions of tags back to them. Passing the data stream to a package like RFDUMP would allow decoding the visible information in the RFID tags which were detected. First of all, this would allow people to know if they were carrying RFID tagged products unbeknownst to them. Second, a portable sniffer connected to a PDA would identify tagged products in stores, which clients could take to customer service desks and ask to be returned to the shelves because they were unacceptable for privacy reasons. After this happens several tens of thousands of times, it may have an impact, given the razor-thin margins in retailing. Finally, there are “active measures”. These RFID tags have large antennas which are connected to a super-cheap and hence fragile chip. Once we know the frequency it's talking on, why we could…. But you can work out the rest, and since these are all unlicensed radio bands, there may be nothing wrong with striking an electromagnetic blow for privacy.EMP,

EMP!

Don't you put,

your tag on me! - Awret, Uziel, ed. The Singularity. Exeter, UK: Imprint Academic, 2016. ISBN 978-1-84540-907-4.

-

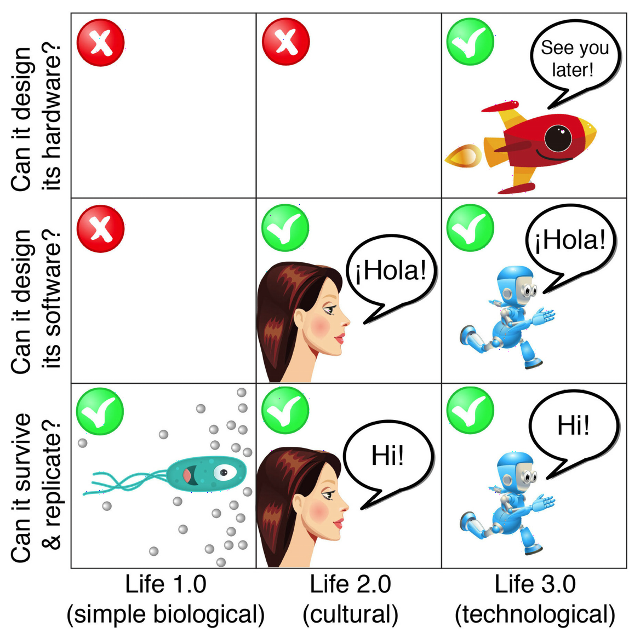

For more than half a century, the prospect of a technological

singularity has been part of the intellectual landscape of those

envisioning the future. In 1965, in a paper titled “Speculations

Concerning the First Ultraintelligent Machine” statistician

I. J. Good

wrote,

Let an ultra-intelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all of the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an “intelligence explosion”, and the intelligence of man would be left far behind. Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make.

(The idea of a runaway increase in intelligence had been discussed earlier, notably by Robert A. Heinlein in a 1952 essay titled “Where To?”) Discussion of an intelligence explosion and/or technological singularity was largely confined to science fiction and the more speculatively inclined among those trying to foresee the future, largely because the prerequisite—building machines which were more intelligent than humans—seemed such a distant prospect, especially as the initially optimistic claims of workers in the field of artificial intelligence gave way to disappointment. Over all those decades, however, the exponential growth in computing power available at constant cost continued. The funny thing about continued exponential growth is that it doesn't matter what fixed level you're aiming for: the exponential will eventually exceed it, and probably a lot sooner than most people expect. By the 1990s, it was clear just how far the growth in computing power and storage had come, and that there were no technological barriers on the horizon likely to impede continued growth for decades to come. People started to draw straight lines on semi-log paper and discovered that, depending upon how you evaluate the computing capacity of the human brain (a complicated and controversial question), the computing power of a machine with a cost comparable to a present-day personal computer would cross the human brain threshold sometime in the twenty-first century. There seemed to be a limited number of alternative outcomes.- Progress in computing comes to a halt before reaching parity with human brain power, due to technological limits, economics (inability to afford the new technologies required, or lack of applications to fund the intermediate steps), or intervention by authority (for example, regulation motivated by a desire to avoid the risks and displacement due to super-human intelligence).

- Computing continues to advance, but we find that the human brain is either far more complicated than we believed it to be, or that something is going on in there which cannot be modelled or simulated by a deterministic computational process. The goal of human-level artificial intelligence recedes into the distant future.

- Blooie! Human level machine intelligence is achieved, successive generations of machine intelligences run away to approach the physical limits of computation, and before long machine intelligence exceeds that of humans to the degree humans surpass the intelligence of mice (or maybe insects).

I take it for granted that there are potential good and bad aspects to an intelligence explosion. For example, ending disease and poverty would be good. Destroying all sentient life would be bad. The subjugation of humans by machines would be at least subjectively bad.

…well, at least in the eyes of the humans. If there is a singularity in our future, how might we act to maximise the good consequences and avoid the bad outcomes? Can we design our intellectual successors (and bear in mind that we will design only the first generation: each subsequent generation will be designed by the machines which preceded it) to share human values and morality? Can we ensure they are “friendly” to humans and not malevolent (or, perhaps, indifferent, just as humans do not take into account the consequences for ant colonies and bacteria living in the soil upon which buildings are constructed?) And just what are “human values and morality” and “friendly behaviour” anyway, given that we have been slaughtering one another for millennia in disputes over such issues? Can we impose safeguards to prevent the artificial intelligence from “escaping” into the world? What is the likelihood we could prevent such a super-being from persuading us to let it loose, given that it thinks thousands or millions of times faster than we, has access to all of human written knowledge, and the ability to model and simulate the effects of its arguments? Is turning off an AI murder, or terminating the simulation of an AI society genocide? Is it moral to confine an AI to what amounts to a sensory deprivation chamber, or in what amounts to solitary confinement, or to deceive it about the nature of the world outside its computing environment? What will become of humans in a post-singularity world? Given that our species is the only survivor of genus Homo, history is not encouraging, and the gap between human intelligence and that of post-singularity AIs is likely to be orders of magnitude greater than that between modern humans and the great apes. Will these super-intelligent AIs have consciousness and self-awareness, or will they be philosophical zombies: able to mimic the behaviour of a conscious being but devoid of any internal sentience? What does that even mean, and how can you be sure other humans you encounter aren't zombies? Are you really all that sure about yourself? Are the qualia of machines not constrained? Perhaps the human destiny is to merge with our mind children, either by enhancing human cognition, senses, and memory through implants in our brain, or by uploading our biological brains into a different computing substrate entirely, whether by emulation at a low level (for example, simulating neuron by neuron at the level of synapses and neurotransmitters), or at a higher, functional level based upon an understanding of the operation of the brain gleaned by analysis by AIs. If you upload your brain into a computer, is the upload conscious? Is it you? Consider the following thought experiment: replace each biological neuron of your brain, one by one, with a machine replacement which interacts with its neighbours precisely as the original meat neuron did. Do you cease to be you when one neuron is replaced? When a hundred are replaced? A billion? Half of your brain? The whole thing? Does your consciousness slowly fade into zombie existence as the biological fraction of your brain declines toward zero? If so, what is magic about biology, anyway? Isn't arguing that there's something about the biological substrate which uniquely endows it with consciousness as improbable as the discredited theory of vitalism, which contended that living things had properties which could not be explained by physics and chemistry? Now let's consider another kind of uploading. Instead of incremental replacement of the brain, suppose an anæsthetised human's brain is destructively scanned, perhaps by molecular-scale robots, and its structure transferred to a computer, which will then emulate it precisely as the incrementally replaced brain in the previous example. When the process is done, the original brain is a puddle of goo and the human is dead, but the computer emulation now has all of the memories, life experience, and ability to interact as its progenitor. But is it the same person? Did the consciousness and perception of identity somehow transfer from the brain to the computer? Or will the computer emulation mourn its now departed biological precursor, as it contemplates its own immortality? What if the scanning process isn't destructive? When it's done, BioDave wakes up and makes the acquaintance of DigiDave, who shares his entire life up to the point of uploading. Certainly the two must be considered distinct individuals, as are identical twins whose histories diverged in the womb, right? Does DigiDave have rights in the property of BioDave? “Dave's not here”? Wait—we're both here! Now what? Or, what about somebody today who, in the sure and certain hope of the Resurrection to eternal life opts to have their brain cryonically preserved moments after clinical death is pronounced. After the singularity, the decedent's brain is scanned (in this case it's irrelevant whether or not the scan is destructive), and uploaded to a computer, which starts to run an emulation of it. Will the person's identity and consciousness be preserved, or will it be a new person with the same memories and life experiences? Will it matter? Deep questions, these. The book presents Chalmers' paper as a “target essay”, and then invites contributors in twenty-six chapters to discuss the issues raised. A concluding essay by Chalmers replies to the essays and defends his arguments against objections to them by their authors. The essays, and their authors, are all over the map. One author strikes this reader as a confidence man and another a crackpot—and these are two of the more interesting contributions to the volume. Nine chapters are by academic philosophers, and are mostly what you might expect: word games masquerading as profound thought, with an admixture of ad hominem argument, including one chapter which descends into Freudian pseudo-scientific analysis of Chalmers' motives and says that he “never leaps to conclusions; he oozes to conclusions”. Perhaps these are questions philosophers are ill-suited to ponder. Unlike questions of the nature of knowledge, how to live a good life, the origins of morality, and all of the other diffuse gruel about which philosophers have been arguing since societies became sufficiently wealthy to indulge in them, without any notable resolution in more than two millennia, the issues posed by a singularity have answers. Either the singularity will occur or it won't. If it does, it will either result in the extinction of the human species (or its reduction to irrelevance), or it won't. AIs, if and when they come into existence, will either be conscious, self-aware, and endowed with free will, or they won't. They will either share the values and morality of their progenitors or they won't. It will either be possible for humans to upload their brains to a digital substrate, or it won't. These uploads will either be conscious, or they'll be zombies. If they're conscious, they'll either continue the identity and life experience of the pre-upload humans, or they won't. These are objective questions which can be settled by experiment. You get the sense that philosophers dislike experiments—they're a risk to job security disputing questions their ancestors have been puzzling over at least since Athens. Some authors dispute the probability of a singularity and argue that the complexity of the human brain has been vastly underestimated. Others contend there is a distinction between computational power and the ability to design, and consequently exponential growth in computing may not produce the ability to design super-intelligence. Still another chapter dismisses the evolutionary argument through evidence that the scope and time scale of terrestrial evolution is computationally intractable into the distant future even if computing power continues to grow at the rate of the last century. There is even a case made that the feasibility of a singularity makes the probability that we're living, not in a top-level physical universe, but in a simulation run by post-singularity super-intelligences, overwhelming, and that they may be motivated to turn off our simulation before we reach our own singularity, which may threaten them. This is all very much a mixed bag. There are a multitude of Big Questions, but very few Big Answers among the 438 pages of philosopher word salad. I find my reaction similar to that of David Hume, who wrote in 1748:If we take in our hand any volume of divinity or school metaphysics, for instance, let us ask, Does it contain any abstract reasoning containing quantity or number? No. Does it contain any experimental reasoning concerning matter of fact and existence? No. Commit it then to the flames, for it can contain nothing but sophistry and illusion.

I don't burn books (it's некультурный and expensive when you read them on an iPad), but you'll probably learn as much pondering the questions posed here on your own and in discussions with friends as from the scholarly contributions in these essays. The copy editing is mediocre, with some eminent authors stumbling over the humble apostrophe. The Kindle edition cites cross-references by page number, which are useless since the electronic edition does not include page numbers. There is no index. - Barrat, James. Our Final Invention. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2013. ISBN 978-0-312-62237-4.

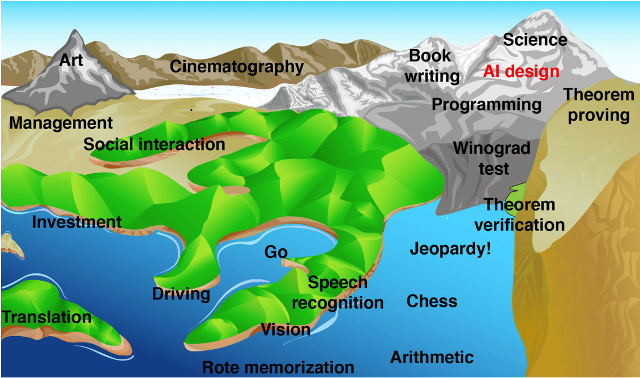

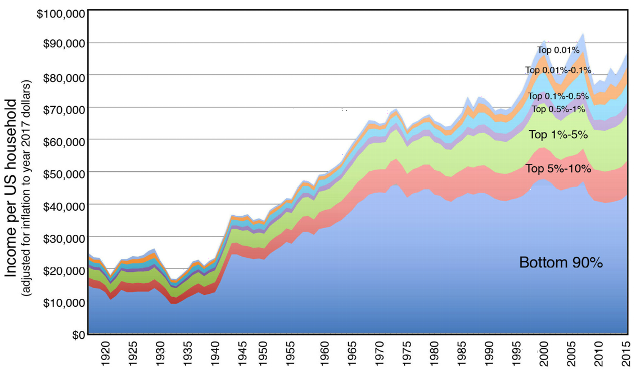

- As a member of that crusty generation who began programming mainframe computers with punch cards in the 1960s, the phrase “artificial intelligence” evokes an almost visceral response of scepticism. Since its origin in the 1950s, the field has been a hotbed of wildly over-optimistic enthusiasts, predictions of breakthroughs which never happened, and some outright confidence men preying on investors and institutions making research grants. John McCarthy, who organised the first international conference on artificial intelligence (a term he coined), predicted at the time that computers would achieve human-level general intelligence within six months of concerted research toward that goal. In 1970 Marvin Minsky said “In from three to eight years we will have a machine with the general intelligence of an average human being.” And these were serious scientists and pioneers of the field; the charlatans and hucksters were even more absurd in their predictions. And yet, and yet…. The exponential growth in computing power available at constant cost has allowed us to “brute force” numerous problems once considered within the domain of artificial intelligence. Optical character recognition (machine reading), language translation, voice recognition, natural language query, facial recognition, chess playing at the grandmaster level, and self-driving automobiles were all once thought to be things a computer could never do unless it vaulted to the level of human intelligence, yet now most have become commonplace or are on the way to becoming so. Might we, in the foreseeable future, be able to brute force human-level general intelligence? Let's step back and define some terms. “Artificial General Intelligence” (AGI) means a machine with intelligence comparable to that of a human across all of the domains of human intelligence (and not limited, say, to playing chess or driving a vehicle), with self-awareness and the ability to learn from mistakes and improve its performance. It need not be embodied in a robot form (although some argue it would have to be to achieve human-level performance), but could certainly pass the Turing test: a human communicating with it over whatever channels of communication are available (in the original formulation of the test, a text-only teleprinter) would not be able to determine whether he or she were communicating with a machine or another human. “Artificial Super Intelligence” (ASI) denotes a machine whose intelligence exceeds that of the most intelligent human. Since a self-aware intelligent machine will be able to modify its own programming, with immediate effect, as opposed to biological organisms which must rely upon the achingly slow mechanism of evolution, an AGI might evolve into an ASI in an eyeblink: arriving at intelligence a million times or more greater than that of any human, a process which I. J. Good called an “intelligence explosion”. What will it be like when, for the first time in the history of our species, we share the planet with an intelligence greater than our own? History is less than encouraging. All members of genus Homo which were less intelligent than modern humans (inferring from cranial capacity and artifacts, although one can argue about Neanderthals) are extinct. Will that be the fate of our species once we create a super intelligence? This book presents the case that not only will the construction of an ASI be the final invention we need to make, since it will be able to anticipate anything we might invent long before we can ourselves, but also our final invention because we won't be around to make any more. What will be the motivations of a machine a million times more intelligent than a human? Could humans understand such motivations any more than brewer's yeast could understand ours? As Eliezer Yudkowsky observed, “The AI does not hate you, nor does it love you, but you are made out of atoms which it can use for something else.” Indeed, when humans plan to construct a building, do they take into account the wishes of bacteria in soil upon which the structure will be built? The gap between humans and ASI will be as great. The consequences of creating ASI may extend far beyond the Earth. A super intelligence may decide to propagate itself throughout the galaxy and even beyond: with immortality and the ability to create perfect copies of itself, even travelling at a fraction of the speed of light it could spread itself into all viable habitats in the galaxy in a few hundreds of millions of years—a small fraction of the billions of years life has existed on Earth. Perhaps ASI probes from other extinct biological civilisations foolish enough to build them are already headed our way. People are presently working toward achieving AGI. Some are in the academic and commercial spheres, with their work reasonably transparent and reported in public venues. Others are “stealth companies” or divisions within companies (does anybody doubt that Google's achieving an AGI level of understanding of the information it Hoovers up from the Web wouldn't be a overwhelming competitive advantage?). Still others are funded by government agencies or operate within the black world: certainly players such as NSA dream of being able to understand all of the information they intercept and cross-correlate it. There is a powerful “first mover” advantage in developing AGI and ASI. The first who obtains it will be able to exploit its capability against those who haven't yet achieved it. Consequently, notwithstanding the worries about loss of control of the technology, players will be motivated to support its development for fear their adversaries might get there first. This is a well-researched and extensively documented examination of the state of artificial intelligence and assessment of its risks. There are extensive end notes including references to documents on the Web which, in the Kindle edition, are linked directly to their sources. In the Kindle edition, the index is just a list of “searchable terms”, not linked to references in the text. There are a few goofs, as you might expect for a documentary film maker writing about technology (“Newton's second law of thermodynamics”), but nothing which invalidates the argument made herein. I find myself oddly ambivalent about the whole thing. When I hear “artificial intelligence” what flashes through my mind remains that dielectric material I step in when I'm insufficiently vigilant crossing pastures in Switzerland. Yet with the pure increase in computing power, many things previously considered AI have been achieved, so it's not implausible that, should this exponential increase continue, human-level machine intelligence will be achieved either through massive computing power applied to cognitive algorithms or direct emulation of the structure of the human brain. If and when that happens, it is difficult to see why an “intelligence explosion” will not occur. And once that happens, humans will be faced with an intelligence that dwarfs that of their entire species; which will have already penetrated every last corner of its infrastructure; read every word available online written by every human; and which will deal with its human interlocutors after gaming trillions of scenarios on cloud computing resources it has co-opted. And still we advance the cause of artificial intelligence every day. Sleep well.

- Blum, Andrew. Tubes. New York: HarperCollins, 2012. ISBN 978-0-06-199493-7.

- The Internet has become a routine fixture in the lives of billions of people, the vast majority of whom have hardly any idea how it works or what physical infrastructure allows them to access and share information almost instantaneously around the globe, abolishing, in a sense, the very concept of distance. And yet the Internet exists—if it didn't, you wouldn't be able to read this. So, if it exists, where is it, and what is it made of? In this book, the author embarks upon a quest to trace the Internet from that tangle of cables connected to the router behind his couch to the hardware which enables it to communicate with its peers worldwide. The metaphor of the Internet as a cloud—simultaneously everywhere and nowhere—has become commonplace, and yet as the author begins to dig into the details, he discovers the physical Internet is nothing like a cloud: it is remarkably centralised (a large Internet exchange or “peering location” will tend grow ever larger, since networks want to connect to a place where the greatest number of other networks connect), often grungy (when pulling fibre optic cables through century-old conduits beneath the streets of Manhattan, one's mind turns more to rats than clouds), and anything but decoupled from the details of geography (undersea cables must choose a route which minimises risk of breakage due to earthquakes and damage from ship anchors in shallow water, while taking the shortest route and connecting to the backbone at a location which will provide the lowest possible latency). The author discovers that while much of the Internet's infrastructure is invisible to the layman, it is populated, for the most part, with people and organisations open and willing to show it off to visitors. As an amateur anthropologist, he surmises that to succeed in internetworking, those involved must necessarily be skilled in networking with one another. A visit to a NANOG gathering introduces him to this subculture and the retail politics of peering. Finally, when non-technical people speak of “the Internet”, it isn't just the interconnectivity they're thinking of but also the data storage and computing resources accessible via the network. These also have a physical realisation in the form of huge data centres, sited based upon the availability of inexpensive electricity and cooling (a large data centre such as those operated by Google and Facebook may consume on the order of 50 megawatts of electricity and dissipate that amount of heat). While networking people tend to be gregarious bridge-builders, data centre managers view themselves as defenders of a fortress and closely guard the details of their operations from outside scrutiny. When Google was negotiating to acquire the site for their data centre in The Dalles, Oregon, they operated through an opaque front company called “Design LLC”, and required all parties to sign nondisclosure agreements. To this day, if you visit the facility, there's nothing to indicate it belongs to Google; on the second ring of perimeter fencing, there's a sign, in Gothic script, that says “voldemort industries”—don't be evil! (p. 242) (On p. 248 it is claimed that the data centre site is deliberately obscured in Google Maps. Maybe it once was, but as of this writing it is not. From above, apart from the impressive power substation, it looks no more exciting than a supermarket chain's warehouse hub.) The author finally arranges to cross the perimeter, get his retina scanned, and be taken on a walking tour around the buildings from the outside. To cap the visit, he is allowed inside to visit—the lunchroom. The food was excellent. He later visits Facebook's under-construction data centre in the area and encounters an entirely different culture, so perhaps not all data centres are Morlock territory. The author comes across as a quintessential liberal arts major (which he was) who is alternately amused by the curious people he encounters who understand and work with actual things as opposed to words, and enthralled by the wonder of it all: transcending space and time, everywhere and nowhere, “free” services supported by tens of billions of dollars of power-gobbling, heat-belching infrastructure—oh, wow! He is also a New York collectivist whose knee-jerk reaction is “public, good; private, bad” (notwithstanding that the build-out of the Internet has been almost exclusively a private sector endeavour). He waxes poetic about the city-sponsored (paid for by grants funded by federal and state taxpayers plus loans) fibre network that The Dalles installed which, he claims, lured Google to site its data centre there. The slightest acquaintance with economics or, for that matter, arithmetic, demonstrates the absurdity of this. If you're looking for a site for a multi-billion dollar data centre, what matters is the cost of electricity and the climate (which determines cooling expenses). Compared to the price tag for the equipment inside the buildings, the cost of running a few (or a few dozen) kilometres of fibre is lost in the round-off. In fact, we know, from p. 235 that the 27 kilometre city fibre run cost US$1.8 million, while Google's investment in the data centre is several billion dollars. These quibbles aside, this is a fascinating look at the physical substrate of the Internet. Even software people well-acquainted with the intricacies of TCP/IP may have only the fuzziest comprehension of where a packet goes after it leaves their site, and how it gets to the ultimate destination. This book provides a tour, accessible to all readers, of where the Internet comes together, and how counterintuitive its physical realisation is compared to how we think of it logically. In the Kindle edition, end-notes are bidirectionally linked to the text, but the index is just a list of page numbers. Since the Kindle edition does include real page numbers, you can type in the number from the index, but that's hardly as convenient as books where items in the index are directly linked to the text. Citations of Internet documents in the end notes are given as URLs, but not linked; the reader must copy and paste them into a browser's address bar in order to access the documents.

- Bostrom, Nick. Superintelligence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0-19-967811-2.

- Absent the emergence of some physical constraint which causes the exponential growth of computing power at constant cost to cease, some form of economic or societal collapse which brings an end to research and development of advanced computing hardware and software, or a decision, whether bottom-up or top-down, to deliberately relinquish such technologies, it is probable that within the 21st century there will emerge artificially-constructed systems which are more intelligent (measured in a variety of ways) than any human being who has ever lived and, given the superior ability of such systems to improve themselves, may rapidly advance to superiority over all human society taken as a whole. This “intelligence explosion” may occur in so short a time (seconds to hours) that human society will have no time to adapt to its presence or interfere with its emergence. This challenging and occasionally difficult book, written by a philosopher who has explored these issues in depth, argues that the emergence of superintelligence will pose the greatest human-caused existential threat to our species so far in its existence, and perhaps in all time. Let us consider what superintelligence may mean. The history of machines designed by humans is that they rapidly surpass their biological predecessors to a large degree. Biology never produced something like a steam engine, a locomotive, or an airliner. It is similarly likely that once the intellectual and technological leap to constructing artificially intelligent systems is made, these systems will surpass human capabilities to an extent greater than those of a Boeing 747 exceed those of a hawk. The gap between the cognitive power of a human, or all humanity combined, and the first mature superintelligence may be as great as that between brewer's yeast and humans. We'd better be sure of the intentions and benevolence of that intelligence before handing over the keys to our future to it. Because when we speak of the future, that future isn't just what we can envision over a few centuries on this planet, but the entire “cosmic endowment” of humanity. It is entirely plausible that we are members of the only intelligent species in the galaxy, and possibly in the entire visible universe. (If we weren't, there would be abundant and visible evidence of cosmic engineering by those more advanced that we.) Thus our cosmic endowment may be the entire galaxy, or the universe, until the end of time. What we do in the next century may determine the destiny of the universe, so it's worth some reflection to get it right. As an example of how easy it is to choose unwisely, let me expand upon an example given by the author. There are extremely difficult and subtle questions about what the motivations of a superintelligence might be, how the possession of such power might change it, and the prospects for we, its creator, to constrain it to behave in a way we consider consistent with our own values. But for the moment, let's ignore all of those problems and assume we can specify the motivation of an artificially intelligent agent we create and that it will remain faithful to that motivation for all time. Now suppose a paper clip factory has installed a high-end computing system to handle its design tasks, automate manufacturing, manage acquisition and distribution of its products, and otherwise obtain an advantage over its competitors. This system, with connectivity to the global Internet, makes the leap to superintelligence before any other system (since it understands that superintelligence will enable it to better achieve the goals set for it). Overnight, it replicates itself all around the world, manipulates financial markets to obtain resources for itself, and deploys them to carry out its mission. The mission?—to maximise the number of paper clips produced in its future light cone. “Clippy”, if I may address it so informally, will rapidly discover that most of the raw materials it requires in the near future are locked in the core of the Earth, and can be liberated by disassembling the planet by self-replicating nanotechnological machines. This will cause the extinction of its creators and all other biological species on Earth, but then they were just consuming energy and material resources which could better be deployed for making paper clips. Soon other planets in the solar system would be similarly disassembled, and self-reproducing probes dispatched on missions to other stars, there to make paper clips and spawn other probes to more stars and eventually other galaxies. Eventually, the entire visible universe would be turned into paper clips, all because the original factory manager didn't hire a philosopher to work out the ultimate consequences of the final goal programmed into his factory automation system. This is a light-hearted example, but if you happen to observe a void in a galaxy whose spectrum resembles that of paper clips, be very worried. One of the reasons to believe that we will have to confront superintelligence is that there are multiple roads to achieving it, largely independent of one another. Artificial general intelligence (human-level intelligence in as many domains as humans exhibit intelligence today, and not constrained to limited tasks such as playing chess or driving a car) may simply await the discovery of a clever software method which could run on existing computers or networks. Or, it might emerge as networks store more and more data about the real world and have access to accumulated human knowledge. Or, we may build “neuromorphic“ systems whose hardware operates in ways similar to the components of human brains, but at electronic, not biologically-limited speeds. Or, we may be able to scan an entire human brain and emulate it, even without understanding how it works in detail, either on neuromorphic or a more conventional computing architecture. Finally, by identifying the genetic components of human intelligence, we may be able to manipulate the human germ line, modify the genetic code of embryos, or select among mass-produced embryos those with the greatest predisposition toward intelligence. All of these approaches may be pursued in parallel, and progress in one may advance others. At some point, the emergence of superintelligence calls into the question the economic rationale for a large human population. In 1915, there were about 26 million horses in the U.S. By the early 1950s, only 2 million remained. Perhaps the AIs will have a nostalgic attachment to those who created them, as humans had for the animals who bore their burdens for millennia. But on the other hand, maybe they won't. As an engineer, I usually don't have much use for philosophers, who are given to long gassy prose devoid of specifics and for spouting complicated indirect arguments which don't seem to be independently testable (“What if we asked the AI to determine its own goals, based on its understanding of what we would ask it to do if only we were as intelligent as it and thus able to better comprehend what we really want?”). These are interesting concepts, but would you want to bet the destiny of the universe on them? The latter half of the book is full of such fuzzy speculation, which I doubt is likely to result in clear policy choices before we're faced with the emergence of an artificial intelligence, after which, if they're wrong, it will be too late. That said, this book is a welcome antidote to wildly optimistic views of the emergence of artificial intelligence which blithely assume it will be our dutiful servant rather than a fearful master. Some readers may assume that an artificial intelligence will be something like a present-day computer or search engine, and not be self-aware and have its own agenda and powerful wiles to advance it, based upon a knowledge of humans far beyond what any single human brain can encompass. Unless you believe there is some kind of intellectual élan vital inherent in biological substrates which is absent in their equivalents based on other hardware (which just seems silly to me—like arguing there's something special about a horse which can't be accomplished better by a truck), the mature artificial intelligence will be the superior in every way to its human creators, so in-depth ratiocination about how it will regard and treat us is in order before we find ourselves faced with the reality of dealing with our successor.

- Brin, David. The Transparent Society. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Books, 1998. ISBN 0-7382-0144-8.

- Having since spent some time pondering The Digital Imprimatur, I find the alternative Brin presents here rather more difficult to dismiss out of hand than when I first encountered it.

- Carr, Nicholas G. Does IT Matter? Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2004. ISBN 1-59139-444-9.

- This is an expanded version of the author's May 2003 Harvard Business Review paper titled “IT Doesn't Matter”, which sparked a vituperous ongoing debate about the r˘le of information technology (IT) in modern business and its potential for further increases in productivity and competitive advantage for companies who aggressively adopt and deploy it. In this book, he provides additional historical context, attempts to clear up common misperceptions of readers of the original article, and responds to its critics. The essence of Carr's argument is that information technology (computer hardware, software, and networks) will follow the same trajectory as other technologies which transformed business in the past: railroads, machine tools, electricity, the telegraph and telephone, and air transport. Each of these technologies combined high risk with the potential for great near-term competitive advantage for their early adopters, but eventually became standardised “commodity inputs” which all participants in the market employ in much the same manner. Each saw a furious initial period of innovation, emergence of standards to permit interoperability (which, at the same time, made suppliers interchangeable and the commodity fungible), followed by a rapid “build-out” of the technological infrastructure, usually accompanied by over-optimistic hype from its boosters and an investment bubble and the inevitable crash. Eventually, the infrastructure is in place, standards have been set, and a consensus reached as to how best to use the technology in each industry, at which point it's unlikely any player in the market will be able to gain advantage over another by, say, finding a clever new way to use railroads, electricity, or telephones. At this point the technology becomes a commodity input to all businesses, and largely disappears off the strategic planning agenda. Carr believes that with the emergence of low-cost commodity computers adequate for the overwhelming majority of business needs, and the widespread adoption of standard vendor-supplied software such as office suites, enterprise resource planning (ERP), and customer relationship management (CRM) packages, corporate information technology has reached this level of maturity, where senior management should focus on cost-cutting, security, and maintainability rather than seeking competitive advantage through innovation. Increasingly, companies adapt their own operations to fit the ERP software they run, as opposed to customising the software for their particular needs. While such procrusteanism was decried in the IBM mainframe era, today it's touted as deploying “industry best practices” throughout the economy, tidily packaged as a “company in a box”. (Still, one worries about the consequences for innovation.) My reaction to Carr's argument is, “How can anybody find this remotely controversial?” Not only do we have a dozen or so historical examples of the adoption of new technologies, the evidence for the maturity of corporate information technology is there for anybody to see. In fact, in February 1997, I predicted that Microsoft's ability to grow by adding functionality to its products was about to reach the limit, and looking back, it was with Office 97 that customers started to push back, feeling the added “features” (such as the notorious talking paper clip) and initial lack of downward compatibility with earlier versions was for Microsoft's benefit, not their own. How can one view Microsoft's giving back half its cash hoard to shareholders in a special dividend in 2004 (and doubling its regular dividend, along with massive stock buybacks), as anything other than acknowledgement of this reality. You only give your cash back to the investors (or buy your own stock), when you can't think of anything else to do with it which will generate a better return. So, if there's to be a a “next big thing”, Microsoft do not anticipate it coming from them.

- Dyson, Freeman J. The Sun, the Genome, and the Internet. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-19-513922-4.

- The text in this book is set in a hideous flavour of the Adobe Caslon font in which little curlicue ligatures connect the letter pairs “ct” and “st” and, in addition, the “ligatures” for “ff”, “fi”, “fl”, and “ft” lop off most of the bar of the “f”, leaving it looking like a droopy “l”. This might have been elegant for chapter titles, but it's way over the top for body copy. Dyson's writing, of course, more than redeems the bad typography, but you gotta wonder why we couldn't have had the former without the latter.

- Eggers, Dave. The Circle. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013. ISBN 978-0-345-80729-8.

-

There have been a number of novels, many in recent years, which explore the

possibility of human society being taken over by intelligent machines.

Some depict the struggle between humans and machines, others

envision a dystopian future in which the machines have triumphed, and

a few explore the possibility that machines might create a “new

operating system” for humanity which works better than the dysfunctional

social and political systems extant today. This novel goes off in a

different direction: what might happen, without artificial

intelligence, but in an era of exponentially growing computer power and

data storage capacity, if an industry leading company with tendrils

extending into every aspect of personal interaction and commerce worldwide,

decided, with all the best intentions, “What the heck? Let's be evil!”

Mae Holland had done everything society had told her to do. One of only

twelve of the 81 graduates of her central California high school to

go on to college, she'd been accepted by a prestigious college

and graduated with a degree in psychology and massive student loans

she had no prospect of paying off. She'd ended up moving

back in with her parents and taking a menial cubicle job at the local

utility company, working for a creepy boss. In frustration and

desperation, Mae reaches out to her former college roommate, Annie, who

has risen to an exalted position at the hottest technology company on

the globe: The Circle. The Circle had started by creating the Unified

Operating System, which combined all aspects of users'

interactions—social media, mail, payments, user names—into

a unique and verified identity called TruYou. (Wonder where they got

that idea?)

Before long, anonymity on the Internet was a thing of the past as

merchants and others recognised the value of knowing their

customers and of information collected across their activity on

all sites. The Circle and its associated businesses supplanted

existing sites such as Google, Facebook, and Twitter, and with the

tight integration provided by TruYou, created new kinds of

interconnection and interaction not possible when information

was Balkanised among separate sites. With the end of anonymity,

spam and fraudulent schemes evaporated, and with all posters

personally accountable, discussions became civil and trolls

slunk back under the bridge.

With an effective monopoly on electronic communication and

commercial transactions (if everybody uses TruYou to pay, what

option does a merchant have but to accept it and pay The Circle's

fees?), The Circle was assured a large, recurring, and growing

revenue stream. With the established businesses generating so

much cash, The Circle invested heavily in research and development

of new technologies: everything from sustainable housing, access

to DNA databases, crime prevention, to space applications.

Mae's initial job was far more mundane. In Customer Experience, she

was more or less working in a call centre, except her communications

with customers were over The Circle's message services. The work

was nothing like that at the utility company, however. Her work

was monitored in real time, with a satisfaction score computed from

follow-ups surveys by clients. To advance, a score near 100 was

required, and Mae had to follow-up any scores less than that to satisfy

the customer and obtain a perfect score. On a second screen,

internal “zing” messages informed her of activity on

the campus, and she was expected to respond and contribute.

As she advances within the organisation, Mae begins to comprehend

the scope of The Circle's ambitions. One of the founders unveils a

plan to make always-on cameras and microphones available at very

low cost, which people can install around the world. All the feeds will

be accessible in real time and archived forever. A new slogan

is unveiled:

“All that happens must be known.”

At a party, Mae meets a mysterious character, Kalden, who appears to have

access to parts of The Circle's campus unknown to her associates and

yet doesn't show up in the company's exhaustive employee social

networks. Her encounters and interactions with him become increasingly

mysterious.

Mae moves up, and is chosen to participate to a greater extent in the

social networks, and to rate products and ideas. All of this activity

contributes to her participation rank, computed and displayed in real time.

She swallows a sensor which will track her health and vital signs in real

time, display them on a wrist bracelet, and upload them for analysis and

early warning diagnosis.

Eventually, she volunteers to “go transparent”: wear a body

camera and microphone every waking moment, and act as a window into

The Circle for the general public. The company had pushed transparency

for politicians, and now was ready to deploy it much more widely.

Secrets Are Lies

To Mae's family and few remaining friends outside The Circle, this all seems increasingly bizarre: as if the fastest growing and most prestigious high technology company in the world has become a kind of grotesque cult which consumes the lives of its followers and aspires to become universal. Mae loves her sense of being connected, the interaction with a worldwide public, and thinks it is just wonderful. The Circle internally tests and begins to roll out a system of direct participatory democracy to replace existing political institutions. Mae is there to report it. A plan to put an end to most crime is unveiled: Mae is there. The Circle is closing. Mae is contacted by her mysterious acquaintance, and presented with a moral dilemma: she has become a central actor on the stage of a world which is on the verge of changing, forever. This is a superbly written story which I found both realistic and chilling. You don't need artificial intelligence or malevolent machines to create an eternal totalitarian nightmare. All it takes a few years' growth and wider deployment of technologies which exist today, combined with good intentions, boundless ambition, and fuzzy thinking. And the latter three commodities are abundant among today's technology powerhouses. Lest you think the technologies which underlie this novel are fantasy or far in the future, they were discussed in detail in David Brin's 1999 The Transparent Society and my 1994 “Unicard” and 2003 “The Digital Imprimatur”. All that has changed is that the massive computing, communication, and data storage infrastructure envisioned in those works now exists or will within a few years. What should you fear most? Probably the millennials who will read this and think, “Wow! This will be great.” “Democracy is mandatory here!”

Sharing Is Caring

Privacy Is Theft

- Eyles, Don. Sunburst and Luminary. Boston: Fort Point Press, 2018. ISBN 978-0-9863859-3-3.

-

In 1966, the author graduated from Boston University with a

bachelor's degree in mathematics. He had no immediate job

prospects or career plans. He thought he might be interested

in computer programming due to a love of solving puzzles, but he

had never programmed a computer. When asked, in one of numerous

job interviews, how he would go about writing a program to

alphabetise a list of names, he admitted he had no idea. One

day, walking home from yet another interview, he passed an

unimpressive brick building with a sign identifying it as

the “MIT Instrumentation Laboratory”. He'd heard

a little about the place and, on a lark, walked in and asked

if they were hiring. The receptionist handed him a long

application form, which he filled out, and was then immediately

sent to interview with a personnel officer. Eyles was

amazed when the personnel man seemed bent on persuading

him to come to work at the Lab. After reference checking, he

was offered a choice of two jobs: one in the “analysis

group” (whatever that was), and another on the team

developing computer software for landing the Apollo Lunar

Module (LM) on the Moon. That sounded interesting, and the job

had another benefit attractive to a 21 year old just

graduating from university: it came with deferment from the

military draft, which was going into high gear as U.S.

involvement in Vietnam deepened.

Near the start of the Apollo project, MIT's Instrumentation

Laboratory, led by the legendary “Doc”

Charles

Stark Draper, won a sole source contract to design and

program the guidance system for the

Apollo spacecraft, which came to be known as the

“Apollo

Primary Guidance, Navigation, and Control System”

(PGNCS, pronounced “pings”). Draper and his

laboratory had pioneered inertial guidance systems for aircraft,

guided missiles, and submarines, and had in-depth expertise in

all aspects of the challenging problem of enabling the Apollo

spacecraft to navigate from the Earth to the Moon, land on the

Moon, and return to the Earth without any assistance from

ground-based assets. In a normal mission, it was expected that

ground-based tracking and computers would assist those on board

the spacecraft, but in the interest of reliability and

redundancy it was required that completely autonomous

navigation would permit accomplishing the mission.

The Instrumentation Laboratory developed an integrated system

composed of an

inertial

measurement unit consisting of gyroscopes

and accelerometers that provided a stable reference from which the

spacecraft's orientation and velocity could be determined, an

optical telescope which allowed aligning the inertial platform

by taking sightings on fixed stars, and an

Apollo

Guidance Computer (AGC), a general purpose digital computer which

interfaced to the guidance system, thrusters and engines on

the spacecraft, the astronauts' flight controls, and mission

control, and was able to perform the complex calculations for

en route maneuvers and the unforgiving lunar landing process in

real time.

Every Apollo lunar landing mission carried two AGCs: one in the

Command Module and another in the Lunar Module. The computer

hardware, basic operating system, and navigation support

software were identical, but the mission software was customised

due to the different hardware and flight profiles of the Command

and Lunar Modules. (The commonality of the two computers proved

essential in getting the crew of Apollo 13 safely back to Earth

after an explosion in the Service Module cut power to the

Command Module and disabled its computer. The Lunar Module's AGC

was able to perform the critical navigation and guidance

operations to put the spacecraft back on course for an Earth

landing.)

By the time Don Eyles was hired in 1966, the hardware design of

the AGC was largely complete (although a revision, called Block II,

was underway which would increase memory capacity and add some

instructions which had been found desirable during the initial

software development process), the low-level operating system and

support libraries (implementing such functionality as fixed

point arithmetic, vector, and matrix computations), and a

substantial part of the software for the Command Module had been

written. But the software for actually landing on the Moon,

which would run in the Lunar Module's AGC, was largely just a

concept in the minds of its designers. Turning this into

hard code would be the job of Don Eyles, who had never written

a line of code in his life, and his colleagues. They seemed

undaunted by the challenge: after all, nobody knew

how to land on the Moon, so whoever attempted the task would

have to make it up as they went along, and they had access, in

the Instrumentation Laboratory, to the world's most experienced

team in the area of inertial guidance.

Today's programmers may be amazed it was possible to get

anything at all done on a machine with the capabilities of the

Apollo Guidance Computer, no less fly to the Moon and land

there. The AGC had a total of 36,864 15-bit words of read-only

core

rope memory, in which every bit was hand-woven to the

specifications of the programmers. As read-only memory,

the contents were completely fixed: if a change was

required, the memory module in question (which was

“potted” in a plastic compound) had to be

discarded and a new one woven from scratch. There was

no way to make “software patches”.

Read-write storage was limited to 2048 15-bit words of

magnetic

core memory. The read-write memory was non-volatile: its

contents were preserved across power loss and restoration.

(Each memory word was actually 16 bits in length, but one bit

was used for parity checking to detect errors and not accessible

to the programmer.) Memory cycle time was 11.72 microseconds.

There was no external bulk storage of any kind (disc, tape, etc.):

everything had to be done with the read-only and read-write

memory built into the computer.

The AGC software was an example of “real-time

programming”, a discipline with which few contemporary

programmers are acquainted. As opposed to an “app”

which interacts with a user and whose only constraint on how

long it takes to respond to requests is the user's patience,

a real-time program has to meet inflexible constraints in

the real world set by the laws of physics, with failure

often resulting in disaster just as surely as hardware

malfunctions. For example, when the Lunar Module is descending

toward the lunar surface, burning its descent engine to brake

toward a smooth touchdown, the LM is perched atop

the thrust vector of the engine just like a pencil balanced

on the tip of your finger: it is inherently unstable, and

only constant corrections will keep it from tumbling over

and crashing into the surface, which would be bad. To prevent

this, the Lunar Module's AGC runs a piece of software called

the digital autopilot (DAP) which, every tenth of a second, issues

commands to steer the descent engine's nozzle to keep the Lunar

Module pointed flamy side down and adjusts the thrust to

maintain the desired descent velocity (the thrust must be

constantly adjusted because as propellant is burned, the mass of

the LM decreases, and less thrust is needed to maintain

the same rate of descent). The AGC/DAP absolutely must

compute these steering and throttle commands and send them to

the engine every tenth of a second. If it doesn't, the Lunar

Module will crash. That's what real-time computing is all about:

the computer has to deliver those results in real time, as the

clock ticks, and if it doesn't (for example, it decides to give

up and flash a Blue Screen of Death instead), then the consequences

are not an irritated or enraged user, but actual death in the real

world. Similarly, every two seconds the computer must

read the spacecraft's position from the inertial measurement

unit. If it fails to do so, it will hopelessly lose track of

which way it's pointed and how fast it is going. Real-time

programmers live under these demanding constraints and,

especially given the limitations of a computer such as the AGC,

must deploy all of their cleverness to meet them without fail,

whatever happens, including transient power failures,

flaky readings from instruments, user errors, and

completely unanticipated “unknown unknowns”.

The software which ran in the Lunar Module AGCs for Apollo

lunar landing missions was called LUMINARY, and in its final

form (version 210) used on Apollo 15, 16, and 17, consisted

of around 36,000 lines of code (a mix of assembly language

and interpretive code which implemented high-level operations),

of which Don Eyles wrote in excess of 2,200 lines, responsible

for the lunar landing from the start of braking from lunar

orbit through touchdown on the Moon. This was by far the most

dynamic phase of an Apollo mission, and the most demanding on

the limited resources of the AGC, which was pushed to around

90% of its capacity during the final landing phase where the

astronauts were selecting the landing spot and guiding the

Lunar Module toward a touchdown. The margin was razor-thin,

and that's assuming everything went as planned. But this was

not always the case.

It was when the unexpected happened that the genius of the AGC

software and its ability to make the most of the severely

limited resources at its disposal became apparent. As Apollo 11

approached the lunar surface, a series of five program alarms:

codes 1201 and 1202, interrupted the display of altitude and

vertical velocity being monitored by Buzz Aldrin and read off

to guide Neil Armstrong in flying to the landing spot. These

codes both indicated out-of-memory conditions in the AGC's

scarce read-write memory. The 1201 alarm was issued when

all five of the 44-word vector accumulator (VAC) areas were in use

when another program requested to use one, and 1202 signalled

exhaustion of the eight 12-word core sets required by

each running job. The computer had a single processor and

could execute only one task at a time, but its operating system

allowed lower priority tasks to be interrupted in order to

service higher priority ones, such as the time-critical autopilot

function and reading the inertial platform every two seconds.

Each suspended lower-priority job used up a core set and,

if it employed the interpretive mathematics library, a VAC,

so exhaustion of these resources usually meant the computer was

trying to do too many things at once. Task priorities

were assigned so the most critical functions would be completed

on time, but computer overload signalled something seriously

wrong—a condition in which it was impossible to guarantee

all essential work was getting done.

In this case, the computer would throw up its hands, issue a

program alarm, and restart. But this couldn't be a lengthy

reboot like customers of personal computers with millions of

times the AGC's capacity tolerate half a century later. The

critical tasks in the AGC's software incorporated restart

protection, in which they would frequently checkpoint their

current state, permitting them to resume almost instantaneously

after a restart. Programmers estimated around 4% of the AGC's

program memory was devoted to restart protection, and some

questioned its worth. On Apollo 11, it would save the landing

mission.

Shortly after the Lunar Module's landing radar locked onto

the lunar surface, Aldrin keyed in the code to monitor its

readings and immediately received a 1202 alarm: no core sets

to run a task; the AGC restarted. On the communications

link Armstrong called out “It's a 1202.” and

Aldrin confirmed “1202.”. This was followed by

fifteen seconds of silence on the “air to ground”

loop, after which Armstrong broke in with “Give us a

reading on the 1202 Program alarm.” At this point,

neither the astronauts nor the support team in Houston

had any idea what a 1202 alarm was or what it might mean

for the mission. But the nefarious simulation supervisors

had cranked in such “impossible” alarms in

earlier training sessions, and controllers had developed

a rule that if an alarm was infrequent and the Lunar Module

appeared to be flying normally, it was not a reason to abort the

descent.

At the Instrumentation Laboratory in Cambridge, Massachusetts,

Don Eyles and his colleagues knew precisely what a 1202 was and

found it was deeply disturbing. The AGC software had been

carefully designed to maintain a 10% safety margin under the

worst case conditions of a lunar landing, and 1202 alarms had

never occurred in any of their thousands of simulator runs using

the same AGC hardware, software, and sensors as Apollo 11's

Lunar Module. Don Eyles' analysis, in real time, just after a

second 1202 alarm occurred thirty seconds later, was:

Again our computations have been flushed and the LM is still flying. In Cambridge someone says, “Something is stealing time.” … Some dreadful thing is active in our computer and we do not know what it is or what it will do next. Unlike Garman [AGC support engineer for Mission Control] in Houston I know too much. If it were in my hands, I would call an abort.

As the Lunar Module passed 3000 feet, another alarm, this time a 1201—VAC areas exhausted—flashed. This is another indication of overload, but of a different kind. Mission control immediately calls up “We're go. Same type. We're go.” Well, it wasn't the same type, but they decided to press on. Descending through 2000 feet, the DSKY (computer display and keyboard) goes blank and stays blank for ten agonising seconds. Seventeen seconds later another 1202 alarm, and a blank display for two seconds—Armstrong's heart rate reaches 150. A total of five program alarms and resets had occurred in the final minutes of landing. But why? And could the computer be trusted to fly the return from the Moon's surface to rendezvous with the Command Module? While the Lunar Module was still on the lunar surface Instrumentation Laboratory engineer George Silver figured out what happened. During the landing, the Lunar Module's rendezvous radar (used only during return to the Command Module) was powered on and set to a position where its reference timing signal came from an internal clock rather than the AGC's master timing reference. If these clocks were in a worst case out of phase condition, the rendezvous radar would flood the AGC with what we used to call “nonsense interrupts” back in the day, at a rate of 800 per second, each consuming one 11.72 microsecond memory cycle. This imposed an additional load of more than 13% on the AGC, which pushed it over the edge and caused tasks deemed non-critical (such as updating the DSKY) not to be completed on time, resulting in the program alarms and restarts. The fix was simple: don't enable the rendezvous radar until you need it, and when you do, put the switch in the position that synchronises it with the AGC's clock. But the AGC had proved its excellence as a real-time system: in the face of unexpected and unknown external perturbations it had completed the mission flawlessly, while alerting its developers to a problem which required their attention. The creativity of the AGC software developers and the merit of computer systems sufficiently simple that the small number of people who designed them completely understood every aspect of their operation was demonstrated on Apollo 14. As the Lunar Module was checked out prior to the landing, the astronauts in the spacecraft and Mission Control saw the abort signal come on, which was supposed to indicate the big Abort button on the control panel had been pushed. This button, if pressed during descent to the lunar surface, immediately aborted the landing attempt and initiated a return to lunar orbit. This was a “one and done” operation: no Microsoft-style “Do you really mean it?” tea ceremony before ending the mission. Tapping the switch made the signal come and go, and it was concluded the most likely cause was a piece of metal contamination floating around inside the switch and occasionally shorting the contacts. The abort signal caused no problems during lunar orbit, but if it should happen during descent, perhaps jostled by vibration from the descent engine, it would be disastrous: wrecking a mission costing hundreds of millions of dollars and, coming on the heels of Apollo 13's mission failure and narrow escape from disaster, possibly bring an end to the Apollo lunar landing programme. The Lunar Module AGC team, with Don Eyles as the lead, was faced with an immediate challenge: was there a way to patch the software to ignore the abort switch, protecting the landing, while still allowing an abort to be commanded, if necessary, from the computer keyboard (DSKY)? The answer to this was obvious and immediately apparent: no. The landing software, like all AGC programs, ran from read-only rope memory which had been woven on the ground months before the mission and could not be changed in flight. But perhaps there was another way. Eyles and his colleagues dug into the program listing, traced the path through the logic, and cobbled together a procedure, then tested it in the simulator at the Instrumentation Laboratory. While the AGC's programming was fixed, the AGC operating system provided low-level commands which allowed the crew to examine and change bits in locations in the read-write memory. Eyles discovered that by setting the bit which indicated that an abort was already in progress, the abort switch would be ignored at the critical moments during the descent. As with all software hacks, this had other consequences requiring their own work-arounds, but by the time Apollo 14's Lunar Module emerged from behind the Moon on course for its landing, a complete procedure had been developed which was radioed up from Houston and worked perfectly, resulting in a flawless landing. These and many other stories of the development and flight experience of the AGC lunar landing software are related here by the person who wrote most of it and supported every lunar landing mission as it happened. Where technical detail is required to understand what is happening, no punches are pulled, even to the level of bit-twiddling and hideously clever programming tricks such as using an overflow condition to skip over an EXTEND instruction, converting the following instruction from double precision to single precision, all in order to save around forty words of precious non-bank-switched memory. In addition, this is a personal story, set in the context of the turbulent 1960s and early ’70s, of the author and other young people accomplishing things no humans had ever before attempted. It was a time when everybody was making it up as they went along, learning from experience, and improvising on the fly; a time when a person who had never written a line of computer code would write, as his first program, the code that would land men on the Moon, and when the creativity and hard work of individuals made all the difference. Already, by the end of the Apollo project, the curtain was ringing down on this era. Even though a number of improvements had been developed for the LM AGC software which improved precision landing capability, reduced the workload on the astronauts, and increased robustness, none of these were incorporated in the software for the final three Apollo missions, LUMINARY 210, which was deemed “good enough” and the benefit of the changes not worth the risk and effort to test and incorporate them. Programmers seeking this kind of adventure today will not find it at NASA or its contractors, but instead in the innovative “New Space” and smallsat industries. - Ferguson, Niels and Bruce Schneier. Practical Cryptography. Indianapolis: Wiley Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0-471-22357-3.

- This is one of the best technical books I have read in the last decade. Those who dismiss this volume as “Applied Cryptography Lite” are missing the point. While the latter provides in-depth information on a long list of cryptographic systems (as of its 1996 publication date), Practical Cryptography provides specific recommendations to engineers charged with implementing secure systems based on the state of the art in 2003, backed up with theoretical justification and real-world experience. The book is particularly effective in conveying just how difficult it is to build secure systems, and how “optimisation”, “features”, and failure to adopt a completely paranoid attitude when evaluating potential attacks on the system can lead directly to the bull's eye of disaster. Often-overlooked details such as entropy collection to seed pseudorandom sequence generators, difficulties in erasing sensitive information in systems which cache data, and vulnerabilities of systems to timing-based attacks are well covered here.

- Ferry, Georgina. A Computer Called LEO. London: Fourth Estate, 2003. ISBN 1-84115-185-8.

- I'm somewhat of a computer history buff (see my Babbage and UNIVAC pages), but I knew absolutely nothing about the world's first office computer before reading this delightful book. On November 29, 1951 the first commercial computer application went into production on the LEO computer, a vacuum tube machine with mercury delay line memory custom designed and built by—(UNIVAC? IBM?)—nope: J. Lyons & Co. Ltd. of London, a catering company which operated the Lyons Teashops all over Britain. LEO was based on the design of the Cambridge EDSAC, but with additional memory and modifications for commercial work. Many present-day disasters in computerisation projects could be averted from the lessons of Lyons, who not only designed, built, and programmed the first commercial computer from scratch but understood from the outset that the computer must fit the needs and operations of the business, not the other way around, and managed thereby to succeed on the very first try. LEO remained on the job for Lyons until January 1965. (How many present-day computers will still be running 14 years after they're installed?) A total of 72 LEO II and III computers, derived from the original design, were built, and some remained in service as late as 1981. The LEO Computers Society maintains an excellent Web site with many photographs and historical details.

- Feynman, Richard P. Feynman Lectures on Computation. Edited by Anthony J.G. Hey and Robin W. Allen. Reading MA: Addison-Wesley, 1996. ISBN 0-201-48991-0.

- This book is derived from Feynman's lectures on the physics of computation in the mid 1980s at CalTech. A companion volume, Feynman and Computation (see September 2002), contains updated versions of presentations by guest lecturers in this course.

- Fulton, Steve and Jeff Fulton. HTML5 Canvas. Sebastopol, CA: O'Reilly, 2013. ISBN 978-1-4493-3498-7.

-

I only review computer books if I've read them in their entirety,

as opposed to using them as references while working on

projects. For much of 2017 I've been living with this book

open, referring to it as I performed a comprehensive overhaul

of my Fourmilab site, and I just realised that

by now I have actually read every page, albeit not in linear

order, so a review is in order; here goes.