« December 2005 | Main | February 2006 »

Monday, January 30, 2006

UNUM: Unicode/HTML/Numeric Character Code Converter Released

Web authors who use characters from other languages, mathematical symbols, fancy punctuation, and other typographic embellishment in their documents often find themselves juggling the Unicode book, an HTML entity reference, and a programmer's calculator to convert back and forth between the various representations. Unum is a stand-alone command line Perl program which contains complete databases of Unicode characters and character blocks and HTML/XHTML character entities, and permits easy lookup and interconversion among all the formats, including octal, decimal, and hexadecimal numbers. The program works best on a recent version of Perl, such as v5.8.5 or later, but requires no Perl library modules.Friday, January 27, 2006

Calendar Converter: Six-Hour Typo Fix, Calendar Queries

An eagle eyed visitor to the site spotted a single character typographical error in Calendar Converter that's been in there ever since it was first posted in 1999. It's fixed now—after six hours of flailing away; to the best of my recollection this is the most time I have ever spent fixing a single fat-finger in more than thirty-five years of programming. The error was in the Hebrew calendar section, where I misspelled the eighth month of the year, חשון (Heshvan), as השון. (If you don't see the Hebrew letters in the last sentence or they're in reverse order, I'm sorry—it's beyond my control; they're properly defined in the document, but your browser may lack Unicode support, not have access to a complete font, or fail to properly render bidirectional text.) To avoid just these kinds of problems, when I created Calendar Converter in 1999, I made the Hebrew month names images which were swapped by the JavaScript code which computes calendar dates. That will work on any browser with JavaScript support, which is a prerequisite for using the page in the first place. Also, back in 1999, I didn't have a good looking Hebrew font on my Linux development machine, so I made the master images with Microsoft Word using the Hebrew Multimode font I developed for the first edition of the on-line Hebrew Bible. (Note: there is at least one error in this font which, since I no longer have the tools with which it was created, nor is the font used any more by the on-line Bible, will not be fixed. I do not recommend you use this font in any case, as modern documents should use Unicode rather than language-specific fonts.) Well, I figured, all I have to do is bring up the document, change the initial “he” to “het”, and that's that. Of course, any time you find yourself thinking “all I have to do” you should pull out the agenda and block out plenty of time for surprises and irritation. This was no exception: due to little changes over the years in each and every software tool in the chain between the source document and the final image, a total of six hours went down the rat hole before I had the new month name images in hand. Had I known it would take that long, naturally I'd have started over with a more modern process, but that isn't how it works—you're always sure the next little fix is all that's needed to get it to work and when it isn't, the good old “sunk investment” fallacy kicks in and keeps you plodding on toward the goal. While I had Calendar Converter torn apart for maintenance, I decided to add something that's been on the list for quite a while: the ability to preset the date displayed in a variety of (but, as yet, not all) calendar systems. This is done by appending a “query string” preceded by a question mark to the URL used to invoke Calendar Converter. Query strings are most often used to supply arguments to CGI programs, but are equally accessible to JavaScript code embedded in pages. You can currently specify dates in either the Gregorian or Julian calendars; as a Julian day or Modified Julian day number and fraction; a Unix time() value; an ISO-8601 year and day or year, week, and day; or a Microsoft Excel day serial number in either the 1900 (PC) or 1904 (Macintosh) date system. The following list gives examples of the various query formats, all set to the date and time of the launch of Sputnik I, 19:28:34 UTC on October 4th, 1957. (The ISO date formats do not permit specification of a time, so the calendar page displayed when you click their links will show the time as midnight.) The delimiter between the date and time in Gregorian and Julian specifications may be any non-numeric character.Using this feature, it's now possible to cite a date in a document which, when clicked, will launch Calendar Converter to display that date in all the available calendars. I'm planning to eventually extend this to allow an additional argument to specify that the result be returned as an XML document which can be easily parsed by the requester, allowing Calendar Converter to be invisibly embedded in Web applications.

- Gregorian

- ?Gregorian=1957-10-04T19:28:34

- Julian Day

- ?JD=2436116.3115

- Modified Julian Day

- ?MJD=36115.8115

- Julian Calendar

- ?Julian=1957-9-21@19:28:34

- Unix time()

- ?unixtime=-386310686

- ISO-8601 Year, Week, and Day

- ?ISO=1957-W40-5

- ISO-8601 Year and Day

- ?ISO=1957-277

- Excel (1900/PC System)

- ?Excel=21097.8115

- Excel (1904/Macintosh System)

- ?Excel1904=19635.8115

Thursday, January 26, 2006

Reading List: The Rise of the Meritocracy

- Young, Michael. The Rise of the Meritocracy. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, [1958] 1994. ISBN 1-56000-704-4.

-

The word “meritocracy” has become so commonplace

in discussions of modern competitive organisations and societies

that you may be surprised to learn the word did not exist before

1958—a year after Sputnik—when the publication of

this most curious book introduced the word and concept into the

English language. This is one of the oddest works of serious

social commentary ever written—so odd, in fact, its author

despaired of its ever seeing print after the manuscript was

rejected by eleven publishers before finally appearing, whereupon

it was quickly republished by Penguin and has been in print ever since,

selling hundreds of thousands of copies and being translated into

seven different languages.

Even though the author was a quintessential “policy wonk”:

he wrote the first postwar manifesto for the British Labour Party,

founded the Open University and the Consumer Association, and

sat in the House of Lords as Lord Young of Dartington, this is

a work of…what shall we call it…utopia? dystopia?

future history? alternative history? satire? ironic social

commentary? science fiction?…beats me. It has also

perplexed many others, including one of the publishers

who rejected it on the grounds that “they never published

Ph.D. theses” without having observed that the book is

cast as a thesis written in the year 2034! Young's dry irony and

understated humour has gone right past many readers, especially

those unacquainted with English satire, moving them to outrage,

as if George Orwell were thought to be advocating Big Brother.

(I am well attuned to this phenomenon, having experienced it myself

with the Unicard

and

Digital

Imprimatur

papers; no matter how obvious you make the irony, somebody,

usually in what passes for universities these days, will take

it seriously and explode in rage and vituperation.)

The meritocracy of this book is nothing like what politicians and

business leaders mean when they parrot the word today (one hopes,

anyway)! In the future envisioned here, psychology and the social

sciences advance to the point that it becomes possible to determine

the IQ of individuals at a young age, and that this IQ, combined with

motivation and effort of the person, is an almost perfect predictor of

their potential achievement in intellectual work. Given this, Britain

is seen evolving from a class system based on heredity and inherited

wealth to a caste system sorted by intelligence, with the

high-intelligence élite “streamed” through special state

schools with their peers, while the lesser endowed are directed toward

manual labour, and the sorry side of the bell curve find employment as

personal servants to the élite, sparing their precious time for the

life of the mind and the leisure and recreation it requires.

And yet the meritocracy is a thoroughly socialist society:

the crème de la crème become the wise civil

servants who direct the deployment of scarce human and financial

capital to the needs of the nation in a highly-competitive global

environment. Inheritance of wealth has been completely abolished,

existing accumulations of wealth confiscated by “capital

levies”, and all salaries made equal (although the

élite, naturally, benefit from a wide variety of employer-provided

perquisites—so is it always, even in merito-egalitopias). The

benevolent state provides special schools for the intelligent progeny

of working class parents, to rescue them from the intellectual damage

their dull families might do, and prepare them for their shining

destiny, while at the same time it provides sports, recreation, and

entertainment to amuse the mentally modest masses when they finish

their daily (yet satisfying, to dullards such as they) toil.

Young's meritocracy is a society where equality of opportunity

has completely triumphed: test scores trump breeding, money,

connections, seniority, ethnicity, accent, religion, and

all of the other ways in which earlier societies sorted

people into classes. The result, inevitably, is drastic

inequality of results—but, hey, everybody gets

paid the same, so it's cool, right? Well, for a while anyway…. As

anybody who isn't afraid to look at the data knows perfectly

well, there is a strong

hereditary component to intelligence.

Sorting people into social classes by intelligence will, over the

generations, cause the mean intelligence of the largely

non-interbreeding classes to drift apart (although there will be

regression to the mean among outliers on each side, mobility among the

classes due to individual variation will preserve or widen the gap).

After a few generations this will result, despite perfect social

mobility in theory, in a segregated caste system almost as rigid as

that of England at the apogee of aristocracy. Just because “the

masses” actually are benighted in this society doesn't

mean they can't cause a lot of trouble, especially if incited by

rabble-rousing bored women from the élite class. (I warned you this

book will enrage those who don't see the irony.) Toward the end of

the book, this conflict is building toward a crisis. Anybody who can

guess the ending ought to be writing satirical future history

themselves.

Actually, I wonder how many of those who missed the satire

didn't actually finish the book or simply judged it by

the title. It is difficult to read a passage like this

one on p. 134 and mistake it for anything else.

Contrast the present — think how different was a meeting in the 2020s of the National Joint Council, which has been retained for form's sake. On the one side sit the I.Q.s of 140, on the other the I.Q.s of 99. On the one side the intellectual magnates of our day, on the other honest, horny-handed workmen more at home with dusters than documents. On the one side the solid confidence born of hard-won achievement; on the other the consciousness of a just inferiority.

Seriously, anybody who doesn't see the satire in this must be none too Swift. Although the book is cast as a retrospective from 2038, and there passing references to atomic stations, home entertainment centres, school trips to the Moon and the like, technologically the world seems very much like that of 1950s. There is one truly frightening innovation, however. On p. 110, discussing the shrinking job market for shop attendants, we're told, “The large shop with its more economical use of staff had supplanted many smaller ones, the speedy spread of self-service in something like its modern form had reduced the number of assistants needed, and piped distribution of milk, tea, and beer was extending rapidly.” To anybody with personal experience with British plumbing and English beer, the mere thought of the latter being delivered through the former is enough to induce dystopic shivers of 1984 magnitude. Looking backward from almost fifty years on, this book can be read as an alternative history of the last half-century. In the eyes of many with a libertarian or conservative inclination, just when the centuries-long battle against privilege and prejudice was finally being won: in the 1950s and early 60s when Young's book appeared, the dream of equal opportunity so eloquently embodied in Dr. Martin Luther King's “I Have a Dream” speech began to evaporate in favour of equality of results (by forced levelling and dumbing down if that's what it took), group identity and entitlements, and the creation of a permanently dependent underclass from which escape was virtually impossible. The best works of alternative history are those which change just one thing in the past and then let the ripples spread outward over the years. You can read this story as a possible future in which equal opportunity really did completely triumph over egalitarianism in the sixties. For those who assume that would have been an unqualifiedly good thing, here is a cautionary tale well worth some serious reflexion.

Sunday, January 22, 2006

Reading List: Our Culture, What's Left of It

- Dalrymple, Theodore. Our Culture, What's Left of It. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2005. ISBN 1-56663-643-4.

- Theodore Dalrymple is the nom de plume of Anthony Daniels, a British physician and psychiatrist who, until his recent retirement, practiced in a prison medical ward and public hospital in Birmingham, England. In his early career, he travelled widely, visiting such earthly paradises as North Korea, Afghanistan, Cuba, Zimbabwe (when it was still Rhodesia), and Tanzania, where he acquired an acute sense of the social prerequisites for the individual disempowerment which characterises the third world. This experience superbly equipped him to diagnose the same maladies in the city centres of contemporary Britain; he is arguably the most perceptive and certainly among the most eloquent contemporary observers of that society. This book is a collection of his columns from City Journal, most dating from 2001 through 2004, about equally divided between “Arts and Letters” and “Society and Politics”. There are gems in both sections: you'll want to re-read Macbeth after reading Dalrymple on the nature of evil and need for boundaries if humans are not to act inhumanly. Among the chapters of social commentary is a prophetic essay which almost precisely forecast the recent violence in France three years before it happened, one of the clearest statements of the inherent problems of Islam in adapting to modernity, and a persuasive argument against drug legalisation by somebody who spent almost his entire career treating the victims of both illegal drugs and the drug war. Dalrymple has decided to conclude his medical career in down-spiralling urban Britain for a life in rural France where, notwithstanding problems, people still know how to live. Thankfully, he will continue his writing. Many of these essays can be found on-line at the City Journal site; I've linked to those I cited in the last paragraph. I find that writing this fine is best enjoyed away from the computer, as ink on paper in a serene time, but it's great that one can now read material on-line to decide whether it's worth springing for the book.

Friday, January 20, 2006

Fourmilab: Network Architecture Drawing Online

After the recent postings about the server and network upgrades here, several people asked if I had a chart which showed the overall architecture after all the dust settled. Well, I had a chart of what I'd planned to do before the dust began to rise, but many's the slip and all that, so this was an excellent excuse to document where things ended up while it was still fresh in my mind, and to experiment with a new vector drawing program at the same time. The result is now posted on the Fourmilab Network Architecture page, which I'll try to keep reasonably up to date as things evolve around here. The image on this page is exported from the master Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) file which was created with Inkscape using symbols from the Open Clip Art Library.Tuesday, January 17, 2006

Fourmilab: Network Upgrade Complete

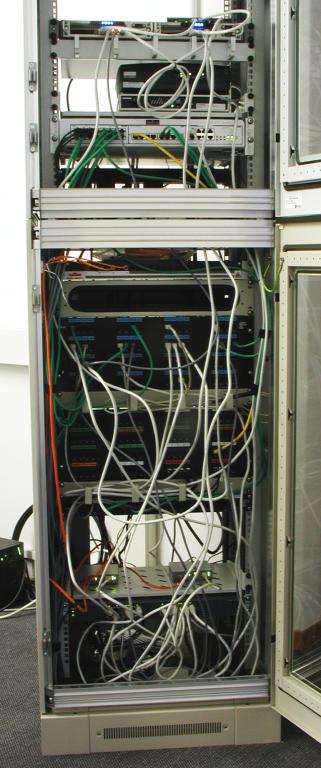

The seemingly endless network infrastructure upgrade at Fourmilab at last seems to be winding down. For the first time in months, it is actually possible to close the doors and install the back

panels on the top and bottom sections of the communications rack (although, as seen in

this picture, I haven't yet actually taken that momentous step). The rack is now 100% free

of “3Con” products. At the top, mounted side by a side in a 1U shell, are

the two Nokia IP265 FreeBSD-based firewalls which were

put into production last

December 8th. Sitting atop them is a

Netgear GS105

Gigabit Ethernet switch for the “external” network; this is the 193.8.230.0/24 address block assigned to Fourmilab by

RIPE.

The only equipment connected directly to this switch are the external interfaces of the

primary and backup firewalls, and the Ethernet port of the Cisco 1720 router which terminates

the Internet connection on this end. The router is the dark box immediately below the cable

guides under the firewalls; it sits atop the Siemens 2 Mbit/sec leased line modem to which it connects. The router also has the ability to establish a 64 Kbit/sec dial-up ISDN connection in the event the leased line fails; given the load on the site, it is difficult to remotely distinguish a fail-over to this backup from a complete outage.

Below the tray which supports the modem and router is the Alcatel OmniPCX Linux-based PBX which provides ISDN wired and DECT wireless telephone service. The PBX has an Ethernet interface, and is managed from

a PC on the local network and, yes, it is behind the firewall and accepts no packets from the outside!

In the bottom half of the rack, the fibre optic patch panel is at the very top; four 65 µm multimode fibres run between the buildings and terminate here and in a small rack in the basement of the house. (Yes, singlemode 9 µm is cooler, but nobody was installing that when these fibres were pulled in 1994. Gigabit Ethernet [1000BASE-SX] works just fine

over 65 µm fibre for a run this short: less than 100 metres.)

Beneath the fibre patch panel is a cable feed-through which is currently unused,

and then the main RJ-45 patch panel (with jacks labeled in blue) where all the

wall outlets in the building terminate. Below that is another cable guide and

then the telephone patch panel

where the external ISDN lines terminate; these are patched to jacks

on the PBX in the top section of the rack. Most of the jacks in this panel are unused

because they used to be connected to the prior Alcatel 4220 PBX, which was mounted

on the wall behind the rack; with its replacement by the rack-mounted OmniPCX, they

have lapsed into desuetude. Below the telephone panel is another cable guide and a 1U patch panel where the 10 lines in the telephone cable between the buildings terminate, then

a large open space which used to be filled with the now-removed 3Con

“hang-o-matic” firewalls and switch.

A tray below the gap supports two Allied Telesyn fibre optic media converters, which interface

the fibre lines between the buildings to the Ethernet network. The one on the

right is the main AT-MC1004SC Gigabit Ethernet converter which bridges

the local network, and at left is an AT-MC101XL 100 MB/s Ethernet converter which acts

as a backup for the Gigabit converter and can be used to extend other networks

(for example, the DMZ on which the servers live, or “toy” networks

assembled for testing) between the buildings.

For the first time in months, it is actually possible to close the doors and install the back

panels on the top and bottom sections of the communications rack (although, as seen in

this picture, I haven't yet actually taken that momentous step). The rack is now 100% free

of “3Con” products. At the top, mounted side by a side in a 1U shell, are

the two Nokia IP265 FreeBSD-based firewalls which were

put into production last

December 8th. Sitting atop them is a

Netgear GS105

Gigabit Ethernet switch for the “external” network; this is the 193.8.230.0/24 address block assigned to Fourmilab by

RIPE.

The only equipment connected directly to this switch are the external interfaces of the

primary and backup firewalls, and the Ethernet port of the Cisco 1720 router which terminates

the Internet connection on this end. The router is the dark box immediately below the cable

guides under the firewalls; it sits atop the Siemens 2 Mbit/sec leased line modem to which it connects. The router also has the ability to establish a 64 Kbit/sec dial-up ISDN connection in the event the leased line fails; given the load on the site, it is difficult to remotely distinguish a fail-over to this backup from a complete outage.

Below the tray which supports the modem and router is the Alcatel OmniPCX Linux-based PBX which provides ISDN wired and DECT wireless telephone service. The PBX has an Ethernet interface, and is managed from

a PC on the local network and, yes, it is behind the firewall and accepts no packets from the outside!

In the bottom half of the rack, the fibre optic patch panel is at the very top; four 65 µm multimode fibres run between the buildings and terminate here and in a small rack in the basement of the house. (Yes, singlemode 9 µm is cooler, but nobody was installing that when these fibres were pulled in 1994. Gigabit Ethernet [1000BASE-SX] works just fine

over 65 µm fibre for a run this short: less than 100 metres.)

Beneath the fibre patch panel is a cable feed-through which is currently unused,

and then the main RJ-45 patch panel (with jacks labeled in blue) where all the

wall outlets in the building terminate. Below that is another cable guide and

then the telephone patch panel

where the external ISDN lines terminate; these are patched to jacks

on the PBX in the top section of the rack. Most of the jacks in this panel are unused

because they used to be connected to the prior Alcatel 4220 PBX, which was mounted

on the wall behind the rack; with its replacement by the rack-mounted OmniPCX, they

have lapsed into desuetude. Below the telephone panel is another cable guide and a 1U patch panel where the 10 lines in the telephone cable between the buildings terminate, then

a large open space which used to be filled with the now-removed 3Con

“hang-o-matic” firewalls and switch.

A tray below the gap supports two Allied Telesyn fibre optic media converters, which interface

the fibre lines between the buildings to the Ethernet network. The one on the

right is the main AT-MC1004SC Gigabit Ethernet converter which bridges

the local network, and at left is an AT-MC101XL 100 MB/s Ethernet converter which acts

as a backup for the Gigabit converter and can be used to extend other networks

(for example, the DMZ on which the servers live, or “toy” networks

assembled for testing) between the buildings.

Below the tray is the Cisco Catalyst 2970 Gigabit Ethernet switch for the internal

network (LAN). All 24 ports on this switch are 10/100/Gigabit automatic switching,

and the switch can be managed either through a console port with Cisco's IOS command

line facility or from a Web interface using a built-in HTTP server. The physically

separate DMZ network on which the public servers reside is connected by redundant

Gigabit Ethernet switches mounted in the

server

rack in the Hall of the Servers downstairs; these switches are patched

directly to the DMZ interfaces of the two firewalls. (Isolating the servers on a DMZ

network means that even if one or more of them should be compromised, they

cannot be used as a “beachhead” to attack machines on the local

network.)

Sitting on the floor

at the bottom of the rack are the adaptor boxes for the four Swisscom ISDN lines connected to

the telephone patch panel; they're intended to be wall mounted, but there isn't

a conveniently located wall, so that's where the installer dumped them

a decade ago and that's where they've been ever since. There used to be a

big rack-mount UPS at the very bottom of the rack, but after its

batteries

melted down a little over a year ago, I replaced it with the floor mount UPS

you can see at the very bottom of the above right photo, having learnt to never again

install a UPS in a rack.

A single cable from the APC SUA1500I UPS powers a 15 outlet strip mounted on the back rail of the rack (see the image at the left) into which is plugged a 6 outlet right-angle power strip (visible at the bottom of the top section of the rack) for “wall wart“ power cubes, which would otherwise devour all

the free outlets on the main power strip.

Below the tray is the Cisco Catalyst 2970 Gigabit Ethernet switch for the internal

network (LAN). All 24 ports on this switch are 10/100/Gigabit automatic switching,

and the switch can be managed either through a console port with Cisco's IOS command

line facility or from a Web interface using a built-in HTTP server. The physically

separate DMZ network on which the public servers reside is connected by redundant

Gigabit Ethernet switches mounted in the

server

rack in the Hall of the Servers downstairs; these switches are patched

directly to the DMZ interfaces of the two firewalls. (Isolating the servers on a DMZ

network means that even if one or more of them should be compromised, they

cannot be used as a “beachhead” to attack machines on the local

network.)

Sitting on the floor

at the bottom of the rack are the adaptor boxes for the four Swisscom ISDN lines connected to

the telephone patch panel; they're intended to be wall mounted, but there isn't

a conveniently located wall, so that's where the installer dumped them

a decade ago and that's where they've been ever since. There used to be a

big rack-mount UPS at the very bottom of the rack, but after its

batteries

melted down a little over a year ago, I replaced it with the floor mount UPS

you can see at the very bottom of the above right photo, having learnt to never again

install a UPS in a rack.

A single cable from the APC SUA1500I UPS powers a 15 outlet strip mounted on the back rail of the rack (see the image at the left) into which is plugged a 6 outlet right-angle power strip (visible at the bottom of the top section of the rack) for “wall wart“ power cubes, which would otherwise devour all

the free outlets on the main power strip.

Sunday, January 15, 2006

Puzzle: Sum of Uniformly Distributed Random Numbers

I have just added a document to the site, Sum of Uniformly Distributed Random Numbers, which I've been developing off and on (mostly off—the duty cycle is barely distinguishable from zero) for about a year. At the moment, it is linked neither to the home page nor the navigation tree, but exclusively to this update log item. Since folks who peruse these pages are disproportionately “bleeding edge” early adopters and even more persnickety and critical (qualities I hold in the highest esteem when it comes to reviewing documents) than the general audience Fourmilab attracts, I thought I'd open up the new document to your scrutiny before inviting the general public to visit it. (I'll probably make this a general practice for new additions to the site unless this experiment results in no useful feedback.) Without giving away the answer, I believe this document could be improved both by additional intuitive analyses and by a crystal-clear explanation of how the crucial integral (you'll know which one I'm speaking of when you read the answer) is evaluated, as opposed to the present description which amounts to saying “abracadabra”. Apart from the content, this document is my first excursion into the ascetic world of XHTML-1.0-Strict document construction. Writing a Strict-compliant document sometimes feels like scribbling with John Calvin looking over your shoulder, ready to administer a severe chastisement the moment a transitory weakness should cause you to indulge in such frivolity as a <font> tag or an align= attribute. Just when you think you've arrived at a modus vivendi with W3C fundamentalism, you discover that the target= attribute in links has been excommunicated on the grounds that it is a “presentation issue” . This capability is supposed to be reinstated by the target module in XHTML 1.1, but that isn't the version most installed browsers support these days. So, there's an awful JavaScript/DOM kludge one employs to fake the effect of the target= attribute; if JavaScript is absent or disabled or the browser doesn't sufficiently support DOM, the worst that happens is that the targeted links open in the main browser window. That, I suppose may be called a “presentation issue”.Saturday, January 14, 2006

Terranova Updated

Since 1995, Terranova has been serving up a new terraformed planet every day to visitors of this site. One of the curious things about image synthesis is that you may consider the images “pretty good”, but after you correct some inaccuracy in the rendering algorithms, the images you generated before now look awful, while the new ones are now deemed “pretty good”. Terranova was originally based upon theppmforge program I contributed to

the Netpbm image processing toolkit. This, in turn, was derived from the “fractal forgery” module I wrote for Autodesk's Chaos: The Software title. When I later made a Terranova screen saver for Windows, I improved the image rendering substantially compared to that of the original ppmforge: stars were drawn as a Gaussian point spread function

depending upon the intensity with the correct colour for their spectral type, star clusters

could create Gaussian enhancement of mean star density, and the range of each

randomised parameter affecting the image could be specified independently.

While the original ppmforge-generated images once looked “pretty good”, they were distinctly tacky next to those generated by the screen saver, so the next obvious step was to integrate the screen saver's image synthesis into the Web page edition of Terranova. At long last, that project is complete and ready for your inspection. Source code for the updated image synthesis program may be downloaded from a link on the

Details

page; it is now a stand-alone program which need not be integrated into a

Netpbm build (although you'll still need assorted Netpbm utilities to post-process

the images it generates).

Since most users browse the Web with higher resolution displays than they did a decade ago, the default image sizes have been increased, although 640×480 images remain available. GIF images have been replaced by PNG, and JPEG is used exclusively for the main high-resolution planet images. All documents are XHTML 1.0 and CSS 2.1 compliant and validated against those standards.

Friday, January 13, 2006

Google Apocalypse

In the title of this piece, I use the word “apocalypse” in its original sense—a prophecy (or, as we've come to say in this mundane, disenchanted world, forecast). However, readers with paranoid tendencies who ponder the privacy and potential monopolistic consequences of what I'm about to discuss may see them as apocalyptic in the more common sense of the word. A lot of people have been speculating about “where Google are going”. Some expected one or more stunning announcements at this year's Consumer Electronics Show (CES), but that didn't happen, so the floor is still open for hunches and hypotheses. What follows is mine—I'm far from the first to come up with this idea, but I have, quite recently, become convinced that this is what Google are up to (or, if it isn't, where they ought to be heading, in my humble estimation). I have no inside information, nor any particular expertise in business forecasting (I am, you'll recall, the guy who predicted Microsoft had peaked in 1997). I don't have an MBA, but I have been called an MBO—master of the bloody obvious; if you consider what follows as obvious as it seems to me, that just might indicate it's a plausible scenario. Imagine if, five or seven years from now, you can buy a Google logo PC from any of a long list of vendors for about US$100. When you turn it on it instantly boots a FreeBSD-derived OS from flash memory (no moving parts in the box at all) and launches the browser which connects to Google and shows your login screen. You log in, and all of your files, mail, and state are there, safely replicated on Google's servers around the world on all that dark fibre, served from the buildings they're buying near major peering points. You can, of course, log in from any browser in the world and see the same view of your state. (This is, of course, just the “thin client” scheme with Google as the monopolistic global server, leveraged with broadband.) JavaScript/AJAX client programs in the browser communicating with the Google server farm will provide the full functionality of all applications now in Microsoft Office plus, of course, the search and context lookup you expect from Google. Google Mail is simply the first of these applications to launch, and it works quite well. Google will provide the same privacy guarantees for user documents as they do for mail. Do you recall the howls when Gmail was announced? Have you noticed that many of the very same people who howled the loudest are among the early adopters of Gmail? Besides, a lot of people will say, “Hey, I feel a lot more secure with my data on Google's servers than on a fragile, rarely backed up Windows PC which can be infected with the keylogger and spyware du jour!”. Of course, security conscious users (government agencies, lawyers, conspiracy theorists, etc.) will not accept losing control over the storage of their data. So Google will sell them Google server software which will run on their own Intranet servers and interface with the same browser clients (which everybody in the world will be trained on) just as if they were using the public service. Google are already doing precisely this with their search engine. Did I mention that there is not a single Microsoft product anywhere in the loop here? Now does it make sense that Steve Ballmer is obsessed with “crushing Google”? The only people who will need a machine with lots of local processing power are the lamers who play kiddie video games. They can continue to buy Windows machines and simply run the Google suite in a browser. But why will PC manufacturers pre-load Windows when 90% of their customers don't need it any more?Reading List: South Park Conservatives

- Anderson, Brian C. South Park Conservatives. Washington: Regnery Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0-89526-019-0.

- Who would have imagined that the advent of “new media”—not just the Internet, but also AM radio after having been freed of the shackles of the “fairness doctrine”, cable television, with its proliferation of channels and the advent of “narrowcasting”, along with the venerable old media of stand-up comedy, cartoon series, and square old books would end up being dominated by conservatives and libertarians? Certainly not the greybeards atop the media pyramid who believed they set the agenda for public discourse and are now aghast to discover that the “people power” they always gave lip service to means just that—the people, not they, actually have the power, and there's nothing they can do to get it back into their own hands. This book chronicles the conservative new media revolution of the past decade. There's nothing about the new media in themselves which has made it a conservative revolution—it's simply that it occurred in a society in which, at the outset, the media were dominated by an elite which were in the thrall of a collectivist ideology which had little or no traction outside the imperial districts from which they declaimed, while the audience they were haranguing had different beliefs entirely which, when they found media which spoke to them, immediately started to listen and tuned out the well-groomed, dulcet-voiced, insipid propagandists of the conventional wisdom. One need only glance at the cratering audience figures for the old media—left-wing urban newspapers, television network news, and “mainstream” news-magazines to see the extent to which they are being shunned. The audience abandoning them is discovering the new media: Web sites, blogs, cable news, talk radio, which (if one follows a broad enough selection), gives a sense of what is actually going on in the world, as opposed to what the editors of the New York Times and the Washington Post decide merits appearing on the front page. Of course, the new media aren't perfect, but they are diverse—which is doubtless why collectivist partisans of coercive consensus so detest them. Some conservatives may be dismayed by the vulgarity of South Park (I'll confess; I'm a big fan), but we partisans of civilisation would be well advised to party down together under a broad and expansive tent. Otherwise, the bastards might kill Kenny with a rocket widget ball.

Monday, January 9, 2006

Reading List: Them: Adventures with Extremists

- Ronson, Jon. Them: Adventures with Extremists. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002. ISBN 0-7432-3321-2.

- Journalist and filmmaker Jon Ronson, intrigued by political and religious extremists in modern Western societies, decided to try to get inside their heads by hanging out with a variety of them as they went about their day to day lives on the fringe. Despite his being Jewish, a frequent contributor to the leftist Guardian newspaper, and often thought of as primarily a humorist, he found himself welcomed into the inner circle of characters as diverse as U.K. Muslim fundamentalist Omar Bakri, Randy Weaver and his daughter Rachel, Colonel Bo Gritz, who he visits while helping to rebuild the Branch Davidian church at Waco, a Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan attempting to remake the image of that organisation with the aid of self-help books, and Dr. Ian Paisley on a missionary visit to Cameroon (where he learns why it's a poor idea to order the “porcupine” in the restaurant when visiting that country). Ronson is surprised to discover that, as incompatible as the doctrines of these characters may be, they are nearly unanimous in believing the world is secretly ruled by a conspiracy of globalist plutocrats who plot their schemes in shadowy venues such as the Bilderberg conferences and the Bohemian Grove in northern California. So, the author decides to check this out for himself. He stalks the secretive Bilderberg meeting to a luxury hotel in Portugal and discovers to his dismay that the Bilderberg Group stalks back, and that the British Embassy can't help you when they're on your tail. Then, he gatecrashes the bizarre owl god ritual in the Bohemian Grove through the clever expedient of walking in right through the main gate. The narrative is entertaining throughout, and generally sympathetic to the extremists he encounters, who mostly come across as sincere (if deluded), and running small-time operations on a limited budget. After becoming embroiled in a controversy during a tour of Canada by David Icke, who claims the world is run by a cabal of twelve foot tall shape-shifting reptilians, and was accused of anti-Semitic hate speech on the grounds that these were “code words” for a Zionist conspiracy, the author ends up concluding that sometimes a twelve foot tall alien lizard is just an alien lizard.

Saturday, January 7, 2006

Reading List: The Living Dead

- Bolchover, David. The Living Dead. Chichester, England: Capstone Publishing, 2005. ISBN 1-84112-656-X.

- If you've ever worked in a large office, you may have occasionally found yourself musing, “Sure, I work hard enough, but what do all those other people do all day?” In this book, David Bolchover, whose personal work experience in two large U.K. insurance companies caused him to ask this question, investigates and comes to the conclusion, “Not very much”. Quoting statistics such as the fact that 70% of Internet pornography site accesses are during the 9 to 5 work day, and that fully one third of mid-week visitors at a large U.K. theme park are employees who called in sick at work, the author discovers that it is remarkably easy to hold down a white collar job in many large organisations while doing essentially no productive work at all—simply showing up every day and collecting paychecks. While the Internet has greatly expanded the scope of goofing off on the job (type "bored at work" into Google and you'll get in excess of sixteen million hits), it is in addition to traditional alternatives to work and, often, easier to measure. The author estimates that as many as 20% of the employees in large offices contribute essentially nothing to their employer's business—these are the “living dead” of the title. Not only are the employers of these people getting nothing for their salaries, even more tragically, the living dead themselves are wasting their entire working careers and a huge portion of their lives in numbing boredom devoid of the satisfaction of doing something worthwhile. In large office environments, there is often so little direct visibility of productivity that somebody who either cannot do the work or simply prefers not to can fall into the cracks for an extended period of time—perhaps until retirement. The present office work environment can be thought of as a holdover from the factory jobs of the industrial revolution, but while it is immediately apparent if a machine operator or production line worker does nothing, this may not be evident for office work. (One of the reasons outsourcing may work well for companies is that it forces them to quantify the value of the contracted work, and the outsourcing companies are motivated to better measure the productivity of their staff since they represent a profit centre, as opposed to a cost centre for the company which outsources.) Back during my blessedly brief career in the management of an organisation which grew beyond the experience base of those who founded it, I found that the only way I could get a sense for what was actually going on in the company, as opposed to what one heard in meetings and read in memoranda, was what I called “Lieutenant Columbo” management—walking around with a little notepad, sitting down with people all over the company, and asking them to explain what they really did—not what their job title said or what their department was supposed to accomplish, but how they actually spent the working day, which was often quite different from what you might have guessed. Another enlightening experience for senior management is to spend a day jacked in to the company switchboard, listening (only) to a sample of the calls coming in from the outside world. I guarantee that anybody who does this for a full working day will end up with pages of notes about things they had no idea were going on. (The same goes for product developers, who should regularly eavesdrop on customer support calls.) But as organisations become huge, the distance between management and where the work is actually done becomes so great that expedients like this cannot bridge the gap: hence the legions of living dead. The insights in this book extend to why so many business books (some seeming like they were generated by the PowerPoint Content Wizard) are awful and what that says about the CEOs who read them, why mumbo-jumbo like “going forward, we need to grow the buy-in for leveraging our core competencies” passes for wisdom in the business world (while somebody who said something like that at the dinner table would, and should, invite a hail of cutlery and vegetables), and why so many middle managers (the indispensable NCOs of the corporate army) are so hideously bad. I fear the author may be too sanguine about the prospects of devolving the office into a world of home-working contractors, all entrepreneurial and self-motivated. I wish that world could come into being, and I sincerely hope it does, but one worries that the inner-directed people who prosper in such an environment are the ones who are already productive even in the stultifying environment of today's office. Perhaps a “middle way” such as Jack Stack's Great Game of Business, combined with the devolving of corporate monoliths into clusters of smaller organisations as suggested in this book may point the way to dezombifying the workplace. If you follow this list, you know how few “business books” I read—as this book so eloquently explains, most are hideous. This is one which will open your eyes and make you think.

Monday, January 2, 2006

Reading List: Greatness

- Hayward, Steven F. Greatness. New York: Crown Forum, 2005. ISBN 0-307-23715-X.

- This book, subtitled "Reagan, Churchill, and the Making of Extraordinary Leaders", examines the parallels between the lives and careers of these two superficially very different men, in search of the roots of their ability, despite having both been underestimated and disdained by their contemporaries (which historical distance has caused many to forget in the case of Churchill, a fact of which Hayward usefully reminds the reader), and considered too old for the challenges facing them when they arrived at the summit of power. The beginning of the Cold War was effectively proclaimed by Churchill's 1946 "Iron Curtain" speech in Fulton, Missouri, and its end foretold by Reagan's "Tear Down this Wall" speech at the Berlin wall in 1987. (Both speeches are worth reading in their entirety, as they have much more to say about the world of their times than the sound bites from them you usually hear.) Interestingly, both speeches were greeted with scorn, and much of Reagan's staff considered it fantasy to imagine and an embarrassment to suggest the Berlin wall falling in the foreseeable future. Only one chapter of the book is devoted to the Cold War; the bulk explores the experiences which formed the character of these men, their self-education in the art of statecraft, their remarkably similar evolution from youthful liberalism in domestic policy to stalwart confrontation of external threats, and their ability to talk over the heads of the political class directly to the population and instill their own optimism when so many saw only disaster and decline ahead for their societies. Unlike the vast majority of their contemporaries, neither Churchill nor Reagan considered Communism as something permanent--both believed it would eventually collapse due to its own, shall we say, internal contradictions. This short book provides an excellent insight into how they came to that prophetic conclusion.