« May 2008 | Main | July 2008 »

Monday, June 30, 2008

Reading List: Wealth, War, and Wisdom

- Biggs, Barton. Wealth, War, and Wisdom. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2008. ISBN 978-0-470-22307-9.

-

Many people, myself included, who have followed financial markets for

an extended period of time, have come to believe what may seem, to

those who have not, a very curious and even mystical thing: that

markets, aggregating the individual knowledge and expectations of

their multitude of participants, have an uncanny way of “knowing”

what the future holds. In retrospect, one can often look at a chart

of broad market indices and see that the market “called”

grand turning points by putting in a long-term bottom or top, even

when those turning points were perceived by few if any people

at the time. One of the noisiest buzzwords of the “Web 2.0”

hype machine is “crowdsourcing”, yet financial markets

have been doing precisely that for centuries, and in an environment

in which the individual participants are not just contributing to

some ratty, ephemeral Web site, but rather putting their own net

worth on the line.

In this book the author, who has spent his long career as a

securities analyst and hedge fund manager, and was a

pioneer of investing in emerging global markets, looks at

the greatest global cataclysm of the twentieth century—World

War II—and explores how well financial markets in

the countries involved identified the key trends and

turning points in the conflict. The results persuasively support

the “wisdom of the market” viewpoint and are a

convincing argument that “the market knows”, even when

its individual participants, media and opinion leaders, and

politicians do not. Consider: the British stock market put in an

all-time historic bottom in June 1940, just as Hitler toured

occupied Paris and, in retrospect, Nazi expansionism in the West

reached its peak. Many Britons expected a German invasion in the

near future, and the Battle of Britain and the Blitz were

still in the future, and yet the market rallied

throughout these dark days. Somehow the market seems to have known

that with the successful evacuation of the British Expeditionary

Force from Dunkerque and the fall of France, the situation, however

dire, was as bad as it was going to get.

In the United States, the Dow Jones Industrial Average declined

throughout 1941 as war clouds darkened, fell further after

Pearl Harbor and the fall of the Philippines, but put in an

all-time bottom in 1942 coincident with the battles of

the Coral Sea and Midway which, in retrospect, but not at the

time, were seen as the key inflection point of the Pacific war.

Note that at this time the U.S. was also at war with Germany

and Italy but had not engaged either in a land battle, and yet

somehow the market “knew” that, whatever the

sacrifices to come, the darkest days were behind.

The wisdom of the markets was also apparent in the ultimate losers

of the conflict, although government price-fixing and disruption

of markets as things got worse obscured the message. The

German CDAX index peaked precisely when the Barbarossa invasion

of the Soviet Union was turned back within sight of the spires of

the Kremlin. At this point the German army was intact, the Soviet

breadbasket was occupied, and the Red Army was in disarray, yet

somehow the market knew that this was the high point. The

great defeat at Stalingrad and the roll-back of the Nazi invaders

were all in the future, but despite propaganda, censorship of letters

from soldiers at the front, and all the control of information a

totalitarian society can employ, once again the market called

the turning point. In Italy, where rampant inflation obscured

nominal price indices, the inflation-adjusted BCI index put in

its high at precisely the moment Mussolini made his alliance

with Hitler, and it was all downhill from there, both for

Italy and its stock market, despite rampant euphoria at the time.

In Japan, the market was heavily manipulated by the Ministry of

Finance and tight control of war news denied investors information

to independently assess the war situation, but by 1943 the market

had peaked in real terms and declined into a collapse thereafter.

In occupied countries, where markets were allowed to function,

they provided insight into the sympathies of their participants.

The French market is particularly enlightening. Clearly, the

investor class was completely on-board with the German

occupation and Vichy. In real terms, the market soared after

the capitulation of France and peaked with the defeat at

Stalingrad, then declined consistently thereafter, with only

a little blip with the liberation of Paris. But then the French

stock market wouldn't be French if it weren't perverse,

would it?

Throughout, the author discusses how individuals living in both the

winners and losers of the war could have best preserved their wealth

and selves, and this is instructive for folks interested in saving

their asses and assets the next time the Four Horsemen sortie from

Hell's own stable. Interestingly, according to Biggs's analysis, so-called

“defensive” investments such as government and top-rated

corporate bonds and short-term government paper (“Treasury Bills”)

performed poorly as stores of wealth in the victor countries and

disastrously in the vanquished. In those societies where equity markets

survived the war (obviously, this excludes those countries in Eastern

Europe occupied by the Soviet Union), stocks were the best financial

instrument in preserving value, although in many cases they did

decline precipitously over the period of the war. How do you ride

out a cataclysm like World War II? There are three key ways: diversification,

diversification, and diversification. You need to diversify across

financial and real assets, including (diversified) portfolios of

stocks, bonds, and bills, as well as real assets such as farmland,

real estate, and hard assets (gold, jewelry, etc.) for really hard

times. You further need to diversify internationally: not just in

the assets you own, but where you keep them. Exchange controls can come

into existence with the stroke of a pen, and that offshore bank

account you keep “just in case” may be all you have

if the worst comes to pass. Thinking about it in that way, do you

have enough there? Finally, you need to diversify your own options

in the world and think about what you'd do if things really

start to go South, and you need to think about it now,

not then. As the author notes in the penultimate paragraph:

…the rich are almost always too complacent, because they cherish the illusion that when things start to go bad, they will have time to extricate themselves and their wealth. It never works that way. Events move much faster than anyone expects, and the barbarians are on top of you before you can escape. … It is expensive to move early, but it is far better to be early than to be late.

This is a quirky book, and not free of flaws. Biggs is a connoisseur of amusing historical anecdotes and sprinkles them throughout the text. I found them a welcome leavening of a narrative filled with human tragedy, folly, and destruction of wealth, but some may consider them a distraction and out of place. There are far more copy-editing errors in this book (including dismayingly many difficulties with the humble apostrophe) than I would expect in a Wiley main catalogue title. But that said, if you haven't discovered the wisdom of the markets for yourself, and are worried about riding out the uncertainties of what appears to be a bumpy patch ahead, this is an excellent place to start.

Sunday, June 29, 2008

Twinkle, Twinkle, Killer Cows

Click on image to enlarge.

Thursday, June 26, 2008

Gnome-o-gram: Financial Derivatives I

One of the principal reasons to contemplate the kinds of defensive and apocalypse-hedge measures discussed in previous gnome-o-grams (1, 2, 3) is the potential for a chain-reaction collapse in financial institutions and markets due to the marking to market of worthless financial derivative instruments held on their books, and the impact on seemingly-hedged players when their counterparty goes bust. Now, unless you follow this stuff, you probably have little or no idea what I just said, and aren't even sure what some of the words mean in this context, whatever it may be. So let's start with a simple example of a derivative transaction, not involving financial instruments at all, but something as simple and down-to-earth as grain. Derivatives of this kind (known today as “commodity futures”) have been traded for more than a century and a half. Suppose you own a bakery, and you know that for the three months beginning next September you're going to need 5,000 bushels of wheat to make the products you'll sell in that period. Your customers require fixed-price bids well in advance, so you need a way to bid for their business at a price which provides you a reasonable return. But if you're preparing a bid, say, nine months before deliveries commence under the contract (assuming you win it), there's a huge uncertainty. While many of your costs are reasonably constant: labour, rent, utilities, etc., the price of your principal raw material, wheat, varies based upon supply and demand and factors, such as the weather and the international trade situation, in ways which are not only unknown but unknowable in principle. You're going to have to buy the wheat then, at whatever the going price may be, so how do you budget now, not knowing the price in the future? This is where futures markets come into play. When you're developing your business plan and preparing bids for your customers in, say, January, you can buy a standardised contract for the delivery of 5,000 bushels of wheat in September, thereby locking in the price you'll have to pay when that month rolls around. What's more, you can buy this delivery contract for a small “margin” deposit, which is much less than the capital you'd have to tie up if you simply bought the wheat now and paid the further expense of storing it in a grain elevator. And you don't have to worry about rats. As the price of wheat inevitably fluctuates between the time you bought the contract and the time you'll actually buy the wheat, the value of the contract will increase or decrease accordingly. If the price of wheat rises, your contract will appreciate: you'll have a paper profit in it, but that's not the point—it's that when you finally sell the contract in September, the profit you make from it will make up for the higher price you'll have to pay for the actual wheat. Conversely, if the price of wheat falls, you'll have a paper loss on the futures contract (and you may have to put up more margin money to maintain the contract), but, come September, your “loss” will be exactly offset by the reduced price you pay for the physical wheat. In this way, you can “lock in” the price of wheat for delivery in September many months in advance and develop your business plan without the uncertainty due to the cost of your principal raw material. Suppose, on the other hand, you're a farmer who, in the short January days in the northern hemisphere is deciding what to plant in the coming spring and how to budget the operations of your farm for the year. You know that based on current grain prices and the productivity of your land, seed and fertiliser costs, and harvesting expenses, wheat looks like an attractive crop, but while you're confident that barring disaster you can produce and deliver 5,000 bushels of wheat, you're worried about the possibility that by the time you're ready to bring it to market, the current heady price may have collapsed and you'll end up taking a loss on your crop. This is precisely the inverse of the baker's situation, and the risk can be similarly mitigated with a futures contract. In this case, you sell 5,000 bushels of wheat for delivery in September, thereby locking in the current price. If the price of wheat falls, your futures contract will appreciate in value, which will compensate you for the lower price you'll receive for your crop, and if wheat rises in price, your “loss” on the contract will be made up by the increased proceeds from the sale of the physical wheat. (Again, the farmer may have to put up additional margin to maintain the contract if the price rises while it is effect.) Now note that neither the baker nor the farmer are shielded from all risks by the futures contract. While they've insulated themselves from the effects of fluctuations in the price of wheat, the baker still needs to worry about his business falling off so that he actually needs less wheat, and ending up with a loss in the futures contract which isn't compensated by purchases of physical wheat, and the farmer still bears the risk of a crop failure, which might leave him with a loss on a futures contract (if the price of wheat goes up, which is the way to bet should crop failures be widespread) that isn't offset by the increased value of his crop. If futures markets consisted exclusively of Farmer Frank selling future delivery contracts to Baker Bob, they would be so small, volatile, illiquid, and expensive as to be useless to both. What makes them work is that the market is open to all kinds of players, including speculators. Frank and Bob are “hedgers”: they are actual producers and consumers of wheat, and have a direct financial interest in its price. A speculator, on the other hand, isn't interested in wheat, but rather the price of wheat, and by buying or selling contracts for the future delivery of wheat is effectively placing a bet that the price of wheat will increase (if buying) or decrease (if selling). The speculator may be trading in wheat because of a belief that inflation is rising or falling, based on estimates of global supply and demand, weather forecasts for growing regions, or predictions from market gurus or a Ouija board, but regardless, the wheat contract is, for the speculator, a purely financial instrument: while ultimately linked to the price of the physical commodity, it is bought and sold on financial markets just like a stock, bond, or currency, and its instantaneous price is set by the balance of buyers and sellers in the futures market (who are, of course, immediately influenced in their actions by real-world events affecting the supply of and demand for wheat). So, there's wheat, the physical commodity, which you can produce, sell, buy, and consume, and then there's “wheat futures”, a financial instrument ultimately linked to the commodity, which producers and consumers can sell and buy to “hedge” their risk and speculators trade on both sides in the hope of profits in the market. The contract for future delivery of wheat is, then, a derivative of the commodity it represents, wheat—it is a purely financial instrument which acts as a proxy for the physical commodity and can be used, at much lower cost than warehousing the actual product, to hedge or speculate in its future value. In this way, we can say that something as mundane as wheat has been “securitised”: turned into a financial instrument which can be traded on an exchange. This is the power of derivatives: almost anything whose cash value can be determined at a given point in time can be the foundation of derivatives based upon it (of ever-increasing abstraction and complexity), which can be bought and sold without ever trading in the actual underlying asset. If this sounds like a fairy castle to you, that's because, in many cases, it is, as we'll see in subsequent gnome-o-grams. (I have chosen not to discuss the details of how, precisely, commodity futures are linked the the physical commodity, which would get us into warehouse receipts, delivery points, grade differentials, and other exquisite details of which even the vast majority of impassioned participants in these markets are ignorant. Besides, they differ from market to market, and we're aiming at an overview of derivatives here.) One note on terminology which will probably be unnecessary for most readers but possibly enlightening for a few. I use the term “speculator” here to identify those participants in a market whose goal is not purchase, sale, or ownership of the actual asset but rather to profit from its appreciation or depreciation during the period it is held. Whenever prices jump, politicians are quick to blame “speculators”, failing to observe (or perhaps perceive, given their beady little eyes and birdlike brains) that since in every futures market there is one seller for every buyer, for every speculator making “obscene profits”, there is another making obscene grimaces as their fortune evaporates. It is speculators, constantly trading in and out of the market, who provide the liquidity (volume of transactions and number of open buy and sell offers at prices close to the market) which permit traders in the physical commodity to execute their orders without creating a large spike in the price to their own detriment. You may hear politicians rail about speculators, but you'll hardly ever hear the people producing and consuming the real stuff denigrate the risk-takers who take the other side of the transaction when they go to buy or sell. Those who denounce speculators should look in the mirror (Latin speculum) whenever they buy a stock because they expect it to “go up”—by doing so, they are speculating. If you buy a stock for the income you expect from its dividends and reinvested profits, then you're truly becoming an owner of the company expecting to profit as it does. Otherwise, you're speculating in its stock. It's cool—we all do it—get used to it. And laugh at the politicians. Some may argue that the term “financial derivatives” should be reserved for derivatives based upon financial instruments as “financial futures” was originally used. Here, I'll use the term for any financial instrument which is derivative of something else, whether it's wheat, livestock, stock indices, currency exchange rates, or whatever. In the next gnome-o-gram, I'll move up one step on the ladder of abstraction and discuss how derivatives can be based upon financial instruments (including other derivatives—the universe, she's recursive!). We have a way to go toward understanding why derivatives pose such a dire threat to the present-day financial infrastructure (indeed, the ones discussed here are entirely benign); I hope said infrastructure holds up until this narrative is concluded.Tuesday, June 24, 2008

Google PageRank Status Add-On for Firefox 3.0

I have written earlier about the handy-dandy add-on for Mozilla Firefox which shows the Google PageRank in the status bar for each page you view. This extension has been running with no problems since I installed the last update at the end of October 2006, but when I downloaded Firefox version 3.0 for testing, Firefox reported the add-on incompatible and refused to install it. An update to this add-on may now be downloaded which has been “repacked” to be compatible with Firefox 3.0. The version indicated in the page is 0.9.8, but the actual add-on reports its version as 0.9.9. I have nothing to do with this add-on except as a satisfied user.Monday, June 23, 2008

Red Bull

Click images to enlarge.

Sunday, June 22, 2008

Reading List: Le Camp des Saints

- Raspail, Jean. Le Camp des Saints. Paris: Robert Laffont, [1973, 1978, 1985] 2006. ISBN 978-2-221-08840-1.

- This is one of the most hauntingly prophetic works of fiction I have ever read. Although not a single word has been changed from its original publication in 1973 to the present edition, it is at times simply difficult to believe you're reading a book which was published thirty-five years ago. The novel is a metaphorical, often almost surreal exploration of the consequences of unrestricted immigration from the third world into the first world: Europe and France in particular, and how the instincts of openness, compassion, and generosity which characterise first world countries can sow the seeds of their destruction if they result in developed countries being submerged in waves of immigration of those who do not share their values, culture, and by their sheer numbers and rate of arrival, cannot be assimilated into the society which welcomes them. The story is built around a spontaneous, almost supernatural, migration of almost a million desperate famine-struck residents from the Ganges on a fleet of decrepit ships, to the “promised land”, and the reaction of the developed countries along their path and in France as they approach and debark. Raspail has perfect pitch when it comes to the prattling of bien pensants, feckless politicians, international commissions chartered to talk about a crisis until it turns into catastrophe, humanitarians bent on demonstrating their good intentions whatever the cost to those they're supposed to be helping and those who fund their efforts, media and pundits bent on indoctrination instead of factual reporting, post-Christian clerics, and the rest of the intellectual scum which rises to the top and suffocates the rationality which has characterised Western civilisation for centuries and created the prosperity and liberty which makes it a magnet for people around the world aspiring to individual achievement. Frankly addressing the roots of Western exceptionalism and the internal rot which imperils it, especially in the context of mass immigration, is a sure way to get yourself branded a racist, and that has, of course been the case with this book. There are, to be sure, many mentions of “whites” and “blacks”, but I perceive no evidence that the author imputes superiority to the first or inferiority to the second: they are simply labels for the cultures from which those actors in the story hail. One character, Hamadura, identified as a dark skinned “Français de Pondichéry” says (p. 357, my translation), “To be white, in my opinion, is not a colour of skin, but a state of mind”. Precisely—anybody, whatever their race or origin, can join the first world, but the first world has a limited capacity to assimilate new arrivals knowing nothing of its culture and history, and risks being submerged if too many arrive, particularly if well-intentioned cultural elites encourage them not to assimilate but instead work for political power and agendas hostile to the Enlightenment values of the West. As Jim Bennett observed, “Democracy, immigration, multiculturalism. Pick any two.” Now, this is a novel from 1973, not a treatise on immigration and multiculturalism in present-day Europe, and the voyage of the fleet of the Ganges is a metaphor for the influx of immigrants into Europe which has already provoked many of the cringing compromises of fundamental Western values prophesied, of which I'm sure most readers in the 1970s would have said, “It can't happen here”. Imagine an editor fearing for his life for having published a cartoon (p. 343), or Switzerland being forced to cede the values which have kept it peaceful and prosperous by the muscle of those who surround it and the intellectual corruption of its own elites. It's all here, and much more. There's even a Pope Benedict XVI (albeit very unlike the present occupant of the throne of St. Peter). This is an ambitious literary work, and challenging for non mother tongue readers. The vocabulary is enormous, including a number of words you won't find even in the Micro Bob. Idioms, many quite obscure (for example “Les carottes sont cuites”—all is lost), abound, and references to them appear obliquely in the text. The apocalyptic tone of the book (whose title is taken from Rev. 20:9) is reinforced by many allusions to that Biblical prophecy. This is a difficult read, which careens among tragedy, satire, and farce, forcing the reader to look beyond political nostrums about the destiny of the West and seriously ask what the consequences of mass immigration without assimilation and the accommodation by the West of values inimical to its own are likely to be. And when you think that Jean Respail saw all of this coming more than three decades ago, it almost makes you shiver. I spent almost three weeks working my way through this book, but although it was difficult, I always looked forward to picking it up, so rewarding was it to grasp the genius of the narrative and the masterful use of the language. An English translation is available. Given the language, idioms, wordplay, and literary allusions in the original French, this work would be challenging to faithfully render into another language. I have not read the translation and cannot comment upon how well it accomplished this formidable task. For more information about the author and his works, visit his official Web site.

Wednesday, June 18, 2008

HotBits: XML Support Added

Ever since its inception in May 1996, the HotBits radioactive random number generator has supported on-line Web access from within applications via the randomX package for Java, which also implements a variety of pseudorandom sequence generation algorithms. It's never been that difficult to obtain HotBits from within an application, as long as it's implemented in a language which provides a reasonably simple way of making Web requests or invoking applications such as Wget which can make them on its behalf. Still, this is the age of “Web 2.0” (one wonders if “Web 2.1” will have all the functionality actually working, without the hype), so everything must conform to the contemporary community standards for such applications. I have just implemented an update to HotBits (Release 3.2) which adds XML as an option for delivery of the requested random data. The XML file format (here is a sample) strictly conforms to the XML standard and the document type description cited within the file. You can request HotBits, specifying an XML reply, and parse it with the XML tools your application framework provides. Unlike other HotBits request formats, the result will always be well-formed XML: error documents are XML and contain a status which can be parsed with the same logic as successful results. The status codes in results are compatible with the HTTP protocol, and successful replies include additional information useful to applications such as the number of requests and bytes remaining before quota limits are imposed. Because it's likely that errors spotted by early adopters who follow these epistles will result in fixes to the application, I haven't yet posted its source code in the usual place. When things settle down in a week or so, I'll update the source code archive on the Web and post a notice of its availability here. Update: The source code for Release 3.2 is now posted. (2008-06-22 18:29 UTC)Sunday, June 15, 2008

Scarecrow

Click on image to enlarge.

Friday, June 13, 2008

Vendor Death Penalty: Hewlett-Packard

As a larval nerd, there were two technology companies I held in the highest esteem: Tektronix and Hewlett-Packard. Tektronix seemed to have a bit more flair: they hailed from the curiously named Beaverton in Oregon, and you'd often find something funny in the complete schematics they shipped with their oscilloscopes, such as the drive circuit for the lower gun of a dual-beam scope being replicated by a bow-legged cowboy labeled “top gun”. But H-P had real class; they printed a hardcover product catalogue, and flipping through it you found not just oscilloscopes, signal generators, and the like, but exotica like rubidium atomic clocks. Not that you were going to buy one, to be sure, but wasn't it cool to know you could, given the budget, and that this company provided you the same specifications for the product they did to customers like the National Bureau of Standards who actually bought such gear? Perhaps it was a part of the H-P Way, a unique corporate culture created by founders Bill and Dave (here is a podcast interview with the author of the book). But there was always something special about H-P, and not surprising that a multitude of breakthrough products including the first scientific calculator, the first programmable calculator, and the first desktop laser printer emerged from their laboratories to define entirely new market categories. Well, that was then, and this is now. Companies mature and enter their dotage, founders pass on management to the next generation, and things change—and how. What was once a technology company whose products scintillated with quality and endured for decades has become an ink company, using the Digital Millennium Copyright Act to shut down those who attempt to enter the aftermarket for ink and toner for their printers, whose own cartridges are accused to be programmed to die on a schedule not linked to quality of results, but rather recurring revenue to the vendor. (Update: Reader S.L. points out that it was Lexmark, not H-P, who invoked the DMCA against toner cloners. My apologies to H-P for the error. [2008-06-13 20:39 UTC]) So, foolish me, knowing all of this but seizing on the easy and familiar solution, when my LaserJet 4 Si Mx printer (bought in 1993 from the original H-P, and built like a Russian tank) finally expired, I replaced it in May of 2004 with an H-P 2300n network printer. This printer was easily configured and worked just fine in both PostScript and PCL modes, but, being a product of the new H-P, died in April 2008, less than four years after its purchase, and without the original toner cartridge having been used up. It reported a normal status on the LCD panel, but simply stopped talking to the network. Printer, meet dumpster; dumpster, meet printer.Fool me once,Then, consumed by a need to print a few documents and not thinking things entirely through, I ordered another H-P network printer, this time a LaserJet P2015n. (This is actually the entry from the current H-P Web site for the P2015dn model, which includes both double sided printing and the network interface. The network-only model no longer appears to be available in the U.S., although it can still be ordered from resellers in Switzerland.)

shame on you.

Fool me twice,

shame on me.

Wednesday, June 11, 2008

Reading List: To the End of the Solar System

- Dewar, James A. To the End of the Solar System. 2nd. ed. Burlington, Canada: Apogee Books, [2004] 2007. ISBN 978-1-894959-68-1.

- If you're seeking evidence that entrusting technology development programs such as space travel to politicians and taxpayer-funded bureaucrats is a really bad idea, this is the book to read. Shortly after controlled nuclear fission was achieved, scientists involved with the Manhattan Project and the postwar atomic energy program realised that a rocket engine using nuclear fission instead of chemical combustion to heat a working fluid of hydrogen would have performance far beyond anything achievable with chemical rockets and could be the key to opening up the solar system to exploration and eventual human settlement. (The key figure of merit for rocket propulsion is “specific impulse”, expressed in seconds, which [for rockets] is simply an odd way of expressing the exhaust velocity. The best chemical rockets have specific impulses of around 450 seconds, while early estimates for solid core nuclear thermal rockets were between 800 and 900 seconds. Note that this does not mean that nuclear rockets were “twice as good” as chemical: because the rocket equation gives the mass ratio [mass of fuelled rocket versus empty mass] as exponential in the specific impulse, doubling that quantity makes an enormous difference in the missions which can be accomplished and drastically reduces the mass which must be lifted from the Earth to mount them.) Starting in 1955, a project began, initially within the U.S. Air Force and the two main weapons laboratories, Los Alamos and Livermore, to explore near-term nuclear rocket propulsion, initially with the goal of an ICBM able to deliver the massive thermonuclear bombs of the epoch. The science was entirely straightforward: build a nuclear reactor able to operate at a high core temperature, pump liquid hydrogen through it at a large rate, expel the hot gaseous hydrogen through a nozzle, and there's your nuclear rocket. Figure out the temperature of exhaust and the weight of the entire nuclear engine, and you can work out the precise performance and mission capability of the system. The engineering was a another matter entirely. Consider: a modern civil nuclear reactor generates about a gigawatt, and is a massive structure enclosed in a huge containment building with thick radiation shielding. It operates at a temperature of around 300° C, heating pressurised water. The nuclear rocket engine, by comparison, might generate up to five gigawatts of thermal power, with a core operating around 2000° C (compared to the 1132° C melting point of its uranium fuel), in a volume comparable to a 55 gallon drum. In operation, massive quantities of liquid hydrogen (a substance whose bulk properties were little known at the time) would be pumped through the core by a turbopump, which would have to operate in an almost indescribable radiation environment which might flash the hydrogen into foam and would certainly reduce all known lubricants to sludge within seconds. And this was supposed to function for minutes, if not hours (later designs envisioned a 10 hour operating lifetime for the reactor, with 60 restarts after being refuelled for each mission). But what if it worked? Well, that would throw open the door to the solar system. Instead of absurd, multi-hundred-billion dollar Mars programs that land a few civil servant spacemen for footprints, photos, and a few rocks returned, you'd end up, for an ongoing budget comparable to that of today's grotesque NASA jobs program, with colonies on the Moon and Mars working their way toward self-sufficiency, regular exploration of the outer planets and moons with mission durations of years, not decades, and the ability to permanently expand the human presence off this planet and simultaneously defend the planet and its biosphere against the kind of Really Bad Day that did in the dinosaurs (and a heck of a lot of other species nobody ever seems to mention). Between 1955 and 1973, the United States funded a series of projects, usually designated as Rover and NERVA, with the potential of achieving all of this. This book is a thoroughly documented (65 pages of end notes) and comprehensive narrative of what went wrong. As is usually the case when government gets involved, almost none of the problems were technological. The battles, and the eventual defeat of the nuclear rocket were due to agencies fighting for turf, bureaucrats seeking to build their careers by backing or killing a project, politicians vying to bring home the bacon for their constituents or kill projects of their political opponents, and the struggle between the executive and legislative branches and the military for control over spending priorities. What never happened among all of the struggles and ups and downs documented here is an actual public debate over the central rationale of the nuclear rocket: should there be, or should there not be, an expansive program (funded within available discretionary resources) to explore, exploit the resources, and settle the solar system? Because if no such program were contemplated, then a nuclear rocket would not be required and funds spent on it squandered. But if such a program were envisioned and deemed worthy of funding, a nuclear rocket, if feasible, would reduce the cost and increase the capability of the program to such an extent that the research and development cost of nuclear propulsion would be recouped shortly after the resulting technology were deployed. But that debate was never held. Instead, the nuclear rocket program was a political football which bounced around for 18 years, consuming 1.4 billion (p. 207) then-year dollars (something like 5.3 billion in today's incredible shrinking greenbacks). Goals were redefined, milestones changed, management shaken up and reorganised, all at the behest of politicians, yet through it all virtually every single technical goal was achieved on time and often well ahead of schedule. Indeed, when the ball finally bounced out of bounds and the 8000 person staff was laid off, dispersing forever their knowledge of the “black art” of fuel element, thermal, and neutronic design constraints for such an extreme reactor, it was not because the project was judged infeasible, but the opposite. The green eyeshade brigade considered the project too likely to succeed, and feared the funding requests for the missions which this breakthrough technological capability would enable. And so ended the possibility of human migration into the solar system for my generation. So it goes. When the rock comes down, the few transient survivors off-planet will perhaps recall their names; they are documented here. There are many things to criticise about this book. It is cheaply made: the text is set in painfully long lines in a small font with narrow margins, which require milliarcsecond-calibrated eye muscles to track from the end of a line to the start of the next. The printing lops off the descenders from the last line of many pages, leaving the reader to puzzle over words like “hvdrooen” and phrases such as “Whv not now?”. The cover seems to incorporate some proprietary substance made of kangaroo hair and discarded slinkies which makes it curl into a tube once you've opened it and read a few pages. Now, these are quibbles which do not detract from the content, but then this is a 300 page paperback without a single colour plate with a cover price of USD26.95. There are a number of factual errors in the text, but none which seriously distort the meaning for the knowledgeable reader; there are few, if any, typographical errors. The author is clearly an enthusiast for nuclear rocket technology, and this sometimes results in over-the-top hyperbole where a dispassionate recounting of the details should suffice. He is a big fan of New Mexico senator Clinton Anderson, a stalwart supporter of the nuclear rocket from its inception through its demise (which coincided with his retirement from the Senate due to health reasons), but only on p. 145 does the author address the detail that the programme was a multi-billion dollar (in an epoch when a billion dollars was real money) pork barrel project for Anderson's state. Flawed—yes, but if you're interested in this little-known backstory of the space program of the last century, whose tawdry history and shameful demise largely explains the sorry state of the human presence in space today, this is the best source of which I'm aware to learn what happened and why. Given the cognitive collapse in the United States (Want to clear a room of Americans? Just say “nuclear!”), I can't share the author's technologically deterministic optimism, “The potential foretells a resurgence at Jackass Flats…” (p. 195), that the legacy of Rover/NERVA will be redeemed by the descendants of those who paid for it only to see it discarded. But those who use this largely forgotten and, in the demographically imploding West, forbidden knowledge to make the leap off our planet toward our destiny in the stars will find the experience summarised here, and the sources cited, an essential starting point for the technologies they'll require to get there. “ ‘Und I'm learning Chinese,’ says Wernher von Braun.”

Monday, June 9, 2008

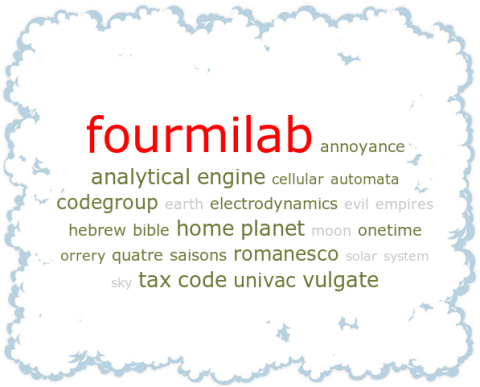

The Front Page

Search engines are an important driver of traffic to Web sites. On a typical day at Fourmilab, about 10,000 initial entries to the site are from people clicking on Google search results and 500 are from Yahoo searches. (These numbers are computed from the “Referrer” HTTP request field; if a user's browser does not report this item, or the request arrives via a proxy or is served from a cache which does not send this field to the server, it will not be counted.) Measured this way, referrals from search engines account for about 1% of visits to Fourmilab. I suspect this number is lower here than for many sites, since this site contains many large documents which engender numerous subsequent navigation clicks, and dynamic content where a user many refresh a page many times after making incremental changes. These subsequent accesses will have intra-site referrer fields, and hence will not be counted as search engine hits even if the user initially arrived via a search engine. To a commercial site with relatively shallow content whose revenue depends upon referrals from search engines, the ranking of its pages in response to relevant queries is crucial to success.| Search Term | Rank |

|---|---|

| Analytical Engine | 2 |

| Annoyance | 6 |

| Cellular Automata | 7 |

| Codegroup | 3 |

| Earth | 8 |

| Electrodynamics | 6 |

| Evil Empires | 8 |

| Hebrew Bible | 5 |

| Home Planet | 1 |

| Moon | 8 |

| Onetime | 6 |

| Orrery | 7 |

| Quatre Saisons | 4 |

| Romanesco | 3 |

| Sky | 10 |

| Solar System | 10 |

| Tax Code | 1 |

| UNIVAC | 3 |

| Vulgate | 2 |

Friday, June 6, 2008

Crossing the Road, Very Slowly

Click image for an enlargement.

Wednesday, June 4, 2008

Keep Your Podder Dry

Last Monday afternoon, (June 2nd, 2008), I had the unanticipated and unpleasant experience of “water testing” a variety of gizmos I carry on my daily walks. (And yes, I wish they were all integrated into one. Patience—it will happen.) I set out under dark and threatening skies, but the radar map showed no precipitation in the region (as of the time it was posted, which is usually within a half hour of the present), so I decided to brave the elements. I chose unwisely. About 20 minutes out, a high wind began to drive a menacing fog/cloud layer in my direction. This picture (click the image for an enlargement) does not begin to convey how ugly this looked as it swept in from the southwest as fast as a locomotive.

Sunday, June 1, 2008

Reading List: The Dumbest Generation

- Bauerlein, Mark. The Dumbest Generation. New York: Tarcher/Penguin, 2008. ISBN 978-1-58542-639-3.

-

The generation born roughly between 1980 and 2000, sometimes dubbed

“Generation Y” or the “Millennial Generation”,

now entering the workforce, the public arena, and exerting an

ever-increasing influence in electoral politics, is the first

generation in human history to mature in an era of ubiquitous

computing, mobile communications, boundless choice in entertainment

delivered by cable and satellite, virtual environments in video games,

and the global connectivity and instant access to the human patrimony

of knowledge afforded by the Internet. In the United States, it is

the largest generational cohort ever, outnumbering the Baby Boomers

who are now beginning to scroll off the screen. Generation Y is the

richest (in terms of disposable income), most ethnically diverse, best

educated (measured by years of schooling), and the most comfortable

with new technologies and the innovative forms of social interactions

they facilitate. Books like

Millennials Rising sing

the praises of this emerging, plugged-in, globally wired

generation, and

Millennial Makeover

(May 2008)

eagerly anticipates the influence they will have

on politics and the culture.

To those of us who interact with members of this generation

regularly through E-mail, Web logs, comments on Web sites,

and personal Web pages, there seems to be a dissonant chord

in this symphony of technophilic optimism. To be blunt,

the kids are clueless. They may be able to multi-task,

juggling mobile phones, SMS text messages, instant Internet

messages (E-mail is so Mom and Dad!), social

networking sites, Twitter, search engines, peer-to-peer

downloads, surfing six hundred cable channels with nothing

on while listening to an iPod and playing a video game,

but when you scratch beneath the monomolecular layer of

frantic media consumption and social interaction with

their peers, there's, as we say on the Web,

no content—they appear

to be almost entirely ignorant of history, culture, the

fine arts, civics, politics, science, economics, mathematics,

and all of the other difficult yet rewarding aspects of

life which distinguish a productive and intellectually

engaged adult from a superannuated child. But then one

worries that one's just muttering the perennial complaints

of curmudgeonly old fogies and that, after all, the kids

are all right. There are, indeed, those who argue that

Everything Bad Is

Good for You: that video games and pop culture

are refining the cognitive, decision-making, and moral

skills of youth immersed in them to never before attained

levels.

But why are they so clueless, then? Well, maybe

they aren't really, and Burgess Shale relics like me have

simply forgotten how little we knew about the real world

at that age. Errr…actually, no—this book, written

by a professor of English at Emory University and former

director of research and analysis for the National Endowment

for the Arts, who experiences first-hand the cognitive capacities

and intellectual endowment of those Millennials who arrive in his

classroom every year, draws upon a wealth of recent research

(the bibliography is 18 pages long) by government

agencies, foundations, and market research organisations,

all without any apparent agenda to promote, which documents

the abysmal levels of knowledge and the ability to apply it

among present-day teenagers and young adults in the U.S.

If there is good news, it is that the new media technologies

have not caused a precipitous collapse in objective measures

of outcomes overall (although there are disturbing statistics

in some regards, including book reading and attendance at

performing arts events). But, on the other hand, the

unprecedented explosion in technology and the maturing

generation's affinity for it and facility in using it have

produced absolutely no objective improvement in their

intellectual performance on a wide spectrum of metrics.

Further, absorption in these new technologies has further

squeezed out time which youth of earlier generations spent

in activities which furthered intellectual development

such as reading for enjoyment, visiting museums and historical

sites, attending and participating in the performing

arts, and tinkering in the garage or basement. This was compounded

by the dumbing down and evisceration of traditional content

in the secondary school curriculum.

The sixties generation's leaders didn't anticipate how their claim of exceptionalism would affect the next generation, and the next, but the sequence was entirely logical. Informed rejection of the past became uninformed rejection of the past, and then complete and unworried ignorance of it. (p. 228)

And it is the latter which is particularly disturbing: as documented extensively, Generation Y knows they're clueless and they're cool with it! In fact, their expectations for success in their careers are entirely discordant with the qualifications they're packing as they venture out to slide down the razor blade of life (pp. 193–198). Or not: on pp. 169–173 we meet the “Twixters”, urban and suburban middle class college graduates between 22 and 30 years old who are still living with their parents and engaging in an essentially adolescent lifestyle: bouncing between service jobs with no career advancement path and settling into no long-term relationship. These sad specimens who refuse to grow up even have their own term of derision: “KIPPERS” Kids In Parents' Pockets Eroding Retirement Savings. In evaluating the objective data and arguments presented here, it's important to keep in mind that correlation does not imply causation. One cannot run controlled experiments on broad-based social trends: only try to infer from the evidence available what might be the cause of the objective outcomes one measures. Many of the characteristics of Generation Y described here might be explained in large part simply by the immersion and isolation of young people in the pernicious peer culture described by Robert Epstein in The Case Against Adolescence (July 2007), with digital technologies simply reinforcing a dynamic in effect well before their emergence, and visible to some extent in the Boomer and Generation X cohorts who matured earlier, without being plugged in 24/7. For another insightful view of Generation Y (by another professor at Emory!), see I'm the Teacher, You're the Student (January 2005). If Millennial Makeover is correct, the culture and politics of the United States is soon to be redefined by the generation now coming of age. This book presents a disturbing picture of what that may entail: a generation with little or no knowledge of history or of the culture of the society they've inherited, and unconcerned with their ignorance, making decisions not in the context of tradition and their intellectual heritage, but of peer popular culture. Living in Europe, it is clear that things have not reached such a dire circumstance here, and in Asia the intergenerational intellectual continuity appears to remain strong. But then, the U.S. was the first adopter of the wired society, and hence may simply be the first to arrive at the scene of the accident. Observing what happens there in the near future may give the rest of the world a chance to change course before their own dumbest generations mature. Paraphrasing Ronald Reagan, the author notes that “Knowledge is never more than one generation away from oblivion.” (p. 186) In an age where a large fraction of all human knowledge is freely accessible to anybody in a fraction of a second, what a tragedy it would be if the “digital natives” ended up, like the pejoratively denigrated “natives” of the colonial era, surrounded by a wealth of culture but ignorant of and uninterested in it. The final chapter is a delightful and stirring defence of culture wars and culture warriors, which argues that only those grounded in knowledge of their culture and equipped with the intellectual tools to challenge accepted norms and conventional wisdom can (for better or worse) change society. Those who lack the knowledge and reasoning skills to be engaged culture warriors are putty in the hands of marketeers and manipulative politicians, which is perhaps why so many of them are salivating over the impending Millennial majority.