Biography

- Aagaard, Finn. Aagaard's Africa. Washington: National Rifle Association, 1991. ISBN 0-935998-62-4.

- The author was born in Kenya in 1932 and lived there until 1977 when, after Kenya's ban on game hunting destroyed his livelihood as a safari guide, he emigrated to the United States, where he died in April 2000. This book recounts his life in Kenya, from boyhood through his career as a professional hunter and guide. If you find the thought of hunting African wildlife repellent, this is not the book for you. It does provide a fine look at Africa and its animals by a man who clearly cherished the land and the beasts which roam it, and viewed the responsible hunter as an integral part of a sustainable environment. A little forensic astronomy allows us to determine the day on which the kudu hunt described on page 124 took place. Aagaard writes, “There was a total eclipse of the sun that afternoon, but it seemed a minor event to us. Laird and I will always remember that day as ‘The Day We Shot The Kudu’.” Checking the canon of 20th century solar eclipses shows that the only total solar eclipse crossing Kenya during the years when Aagaard was hunting there was on June 30th, 1973, a seven minute totality once in a lifetime spectacle. So, the kudu hunt had to be that morning. To this amateur astronomer, no total solar eclipse is a minor event, and the one I saw in Africa will forever remain a major event in my life. A solar eclipse with seven minutes of totality is something I shall never live to see (the next occurring on June 25th, 2150), so I would have loved to have seen the last and would never have deemed it a “minor event”, but then I've never shot a kudu the morning of an eclipse! This book is out of print and used copies, at this writing, are offered at outrageous prices. I bought this book directly from the NRA more than a decade ago—books sometimes sit on my shelf a long time before I read them. I wouldn't pay more than about USD 25 for a used copy.

- Aldrin, Buzz. Magnificent Desolation. London: Bloomsbury, 2009. ISBN 978-1-4088-0416-2.

- What do you do with the rest of your life when you were one of the first two humans to land on the Moon before you celebrated your fortieth birthday? This relentlessly candid autobiography answers that question for Buzz Aldrin (please don't write to chastise me for misstating his name: while born as Edwin Eugene Aldrin, Jr., he legally changed his name to Buzz Aldrin in 1979). Life after the Moon was not easy for Aldrin. While NASA trained their astronauts for every imaginable in-flight contingency, they prepared them in no way for their celebrity after the mission was accomplished, and detail-oriented engineers were suddenly thrust into the public sphere, sent as goodwill ambassadors around the world with little or no concern for the effects upon their careers or family lives. All of this was not easy for Aldrin, and in this book he chronicles his marriages (3), divorces (2), battles against depression and alcoholism, search for a post-Apollo career, which included commanding the U.S. Air Force test pilot school at Edwards Air Force Base, writing novels, serving as a corporate board member, and selling Cadillacs. In the latter part of the book he describes his recent efforts to promote space tourism, develop affordable private sector access to space, and design an architecture which will permit exploration and exploitation of the resources of the Moon, Mars and beyond with budgets well below those of the Apollo era. This book did not work for me. Buzz Aldrin has lived an extraordinary life: he developed the techniques for orbital rendezvous used to this day in space missions, pioneered underwater neutral buoyancy training for spacewalks then performed the first completely successful extra-vehicular activity on Gemini 12, demonstrating that astronauts can do useful work in the void, and was the second man to set foot on the Moon. But all of this is completely covered in the first three chapters, and then we have 19 more chapters describing his life after the Moon. While I'm sure it's fascinating if you've lived though it yourself, it isn't necessarily all that interesting to other people. Aldrin comes across as, and admits to being, self-centred, and this is much in evidence here. His adventures, ups, downs, triumphs, and disappointments in the post-Apollo era are those that many experience in their own lives, and I don't find them compelling to read just because the author landed on the Moon forty years ago. Buzz Aldrin is not just an American hero, but a hero of the human species: he was there when the first naked apes reached out and set foot upon another celestial body (hear what he heard in his headphones during the landing). His life after that epochal event has been a life well-lived, and his efforts to open the high frontier to ordinary citizens are to be commended. This book is his recapitulation of his life so far, but I must confess I found the post-Apollo narrative tedious. But then, they wouldn't call him Buzz if there wasn't a buzz there! Buzz is 80 years old and envisions living another 20 or so. Works for me: I'm around 60, so that gives me 40 or so to work with. Given any remotely sane space policy, Buzz could be the first man to set foot on Mars in the next 15 years, and Lois could be the first woman. Maybe I and the love of my life will be among the crew to deliver them their supplies and the essential weasels for their planetary colonisation project. A U.S. edition is available.

- Aron, Leon. Yeltsin: A Revolutionary Life. New York: St. Martin's, 2000. ISBN 0-312-25185-8.

- Bin Ladin, Carmen. The Veiled Kingdom. London: Virago Press, 2004. ISBN 1-84408-102-8.

- Carmen Bin Ladin, a Swiss national with a Swiss father and Iranian mother, married Yeslam Bin Ladin in 1974 and lived in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia from 1976 to 1985. Yeslam Bin Ladin is one of the 54 sons and daughters sired by that randy old goat Sheikh Mohamed Bin Laden on his twenty-two wives including, of course, murderous nutball Osama. (There is no unique transliteration of Arabic into English. Yeslam spells his name “Bin Ladin”, while other members of the clan use “Bin Laden”, the most common spelling in the media. This book uses “Bin Ladin” when referring to Yeslam, Carmen, and their children, and “Bin Laden” when referring to the clan or other members of it.) This autobiography provides a peek, through the eyes of a totally Westernised woman, into the bizarre medieval life of Saudi women and the arcane customs of that regrettable kingdom. The author separated from her husband in 1988 and presently lives in Geneva. The link above is to a U.K. paperback edition. I believe the same book is available in the U.S. under the title Inside the Kingdom : My Life in Saudi Arabia, but at the present time only in hardcover.

- Brookhiser, Richard. Founding Father. New York: Free Press, 1996. ISBN 0-684-83142-2.

- This thin (less than 200 pages of main text) volume is an enlightening biography of George Washington. It is very much a moral biography in the tradition of Plutarch's Lives; the focus is on Washington's life in the public arena and the events in his life which formed his extraordinary character. Reading Washington's prose, one might assume that he, like many other framers of the U.S. Constitution, had an extensive education in the classics, but in fact his formal education ended at age 15, when he became an apprentice surveyor—among U.S. presidents, only Andrew Johnson had less formal schooling. Washington's intelligence and voracious reading—his library numbered more than 900 books at his death—made him the intellectual peer of his just sprouting Ivy League contemporaries. One historical footnote I'd never before encountered is the tremendous luck the young U.S. republic had in escaping the risk of dynasty—among the first five U.S. presidents, only John Adams had a son who survived to adulthood (and his eldest son, John Quincy Adams, became the sixth president).

- Brown, Brandon R. Planck. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-021947-5.

-

Theoretical physics is usually a young person's game. Many of the

greatest breakthroughs have been made by researchers in their

twenties, just having mastered existing theories while remaining

intellectually flexible and open to new ideas. Max Planck,

born in 1858, was an exception to this rule. He spent most of his

twenties living with his parents and despairing of finding a

paid position in academia. He was thirty-six when he took on

the project of understanding heat radiation, and forty-two

when he explained it in terms which would launch the quantum

revolution in physics. He was in his fifties when he discovered

the zero-point energy of the vacuum, and remained engaged and active

in science until shortly before his death in 1947 at the age of

89. As theoretical physics editor for the then most

prestigious physics journal in the world,

Annalen der Physik, in 1905 he

approved publication of Einstein's special theory of relativity,

embraced the new ideas from a young outsider with neither a Ph.D. nor

an academic position, extended the theory in his own work in

subsequent years, and was instrumental in persuading Einstein

to come to Berlin, where he became a close friend.

Sometimes the simplest puzzles lead to the most profound of insights.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the radiation emitted by

heated bodies was such a conundrum. All objects emit electromagnetic

radiation due to the thermal motion of their molecules. If an object

is sufficiently hot, such as the filament of an incandescent lamp or

the surface of the Sun, some of the radiation will fall into the

visible range and be perceived as light. Cooler objects emit in

the infrared or lower frequency bands and can be detected by

instruments sensitive to them. The radiation emitted by a hot

object has a characteristic spectrum (the distribution of energy

by frequency), and has a peak which depends only upon the

temperature of the body. One of the simplest cases is that of a

black body,

an ideal object which perfectly absorbs all incident radiation.

Consider an ideal closed oven which loses no heat to the outside.

When heated to a given temperature, its walls will absorb and

re-emit radiation, with the spectrum depending upon its temperature.

But the

equipartition

theorem, a cornerstone of

statistical

mechanics, predicted that the absorption and re-emission of

radiation in the closed oven would result in a ever-increasing

peak frequency and energy, diverging to infinite temperature, the

so-called

ultraviolet

catastrophe. Not only did this violate the law of conservation of

energy, it was an affront to common sense: closed ovens do not explode

like nuclear bombs. And yet the theory which predicted this behaviour,

the

Rayleigh-Jeans

law,

made perfect sense based upon the motion of atoms and molecules,

correctly predicted numerous physical phenomena, and was correct for

thermal radiation at lower temperatures.

At the time Planck took up the problem of thermal radiation,

experimenters in Germany were engaged in measuring the radiation

emitted by hot objects with ever-increasing precision, confirming

the discrepancy between theory and reality, and falsifying several

attempts to explain the measurements. In December 1900, Planck

presented his new theory of black body radiation and what is

now called

Planck's Law

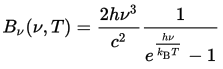

at a conference in Berlin. Written in modern notation, his

formula for the energy emitted by a body of temperature

T at frequency ν is:

This equation not only correctly predicted the results measured in the laboratories, it avoided the ultraviolet catastrophe, as it predicted an absolute cutoff of the highest frequency radiation which could be emitted based upon an object's temperature. This meant that the absorption and re-emission of radiation in the closed oven could never run away to infinity because no energy could be emitted above the limit imposed by the temperature. Fine: the theory explained the measurements. But what did it mean? More than a century later, we're still trying to figure that out. Planck modeled the walls of the oven as a series of resonators, but unlike earlier theories in which each could emit energy at any frequency, he constrained them to produce discrete chunks of energy with a value determined by the frequency emitted. This had the result of imposing a limit on the frequency due to the available energy. While this assumption yielded the correct result, Planck, deeply steeped in the nineteenth century tradition of the continuum, did not initially suggest that energy was actually emitted in discrete packets, considering this aspect of his theory “a purely formal assumption.” Planck's 1900 paper generated little reaction: it was observed to fit the data, but the theory and its implications went over the heads of most physicists. In 1905, in his capacity as editor of Annalen der Physik, he read and approved the publication of Einstein's paper on the photoelectric effect, which explained another physics puzzle by assuming that light was actually emitted in discrete bundles with an energy determined by its frequency. But Planck, whose equation manifested the same property, wasn't ready to go that far. As late as 1913, he wrote of Einstein, “That he might sometimes have overshot the target in his speculations, as for example in his light quantum hypothesis, should not be counted against him too much.” Only in the 1920s did Planck fully accept the implications of his work as embodied in the emerging quantum theory.

The equation for Planck's Law contained two new fundamental physical constants: Planck's constant (h) and Boltzmann's constant (kB). (Boltzmann's constant was named in memory of Ludwig Boltzmann, the pioneer of statistical mechanics, who committed suicide in 1906. The constant was first introduced by Planck in his theory of thermal radiation.) Planck realised that these new constants, which related the worlds of the very large and very small, together with other physical constants such as the speed of light (c), the gravitational constant (G), and the Coulomb constant (ke), allowed defining a system of units for quantities such as length, mass, time, electric charge, and temperature which were truly fundamental: derived from the properties of the universe we inhabit, and therefore comprehensible to intelligent beings anywhere in the universe. Most systems of measurement are derived from parochial anthropocentric quantities such as the temperature of somebody's armpit or the supposed distance from the north pole to the equator. Planck's natural units have no such dependencies, and when one does physics using them, equations become simpler and more comprehensible. The magnitudes of the Planck units are so far removed from the human scale they're unlikely to find any application outside theoretical physics (imagine speed limit signs expressed in a fraction of the speed of light, or road signs giving distances in Planck lengths of 1.62×10−35 metres), but they reflect the properties of the universe and may indicate the limits of our ability to understand it (for example, it may not be physically meaningful to speak of a distance smaller than the Planck length or an interval shorter than the Planck time [5.39×10−44 seconds]).

Planck's life was long and productive, and he enjoyed robust health (he continued his long hikes in the mountains into his eighties), but was marred by tragedy. His first wife, Marie, died of tuberculosis in 1909. He outlived four of his five children. His son Karl was killed in 1916 in World War I. His two daughters, Grete and Emma, both died in childbirth, in 1917 and 1919. His son and close companion Erwin, who survived capture and imprisonment by the French during World War I, was arrested and executed by the Nazis in 1945 for suspicion of involvement in the Stauffenberg plot to assassinate Hitler. (There is no evidence Erwin was a part of the conspiracy, but he was anti-Nazi and knew some of those involved in the plot.) Planck was repulsed by the Nazis, especially after a private meeting with Hitler in 1933, but continued in his post as the head of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society until 1937. He considered himself a German patriot and never considered emigrating (and doubtless his being 75 years old when Hitler came to power was a consideration). He opposed and resisted the purging of Jews from German scientific institutions and the campaign against “Jewish science”, but when ordered to dismiss non-Aryan members of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, he complied. When Heisenberg approached him for guidance, he said, “You have come to get my advice on political questions, but I am afraid I can no longer advise you. I see no hope of stopping the catastrophe that is about to engulf all our universities, indeed our whole country. … You simply cannot stop a landslide once it has started.” Planck's house near Berlin was destroyed in an Allied bombing raid in February 1944, and with it a lifetime of his papers, photographs, and correspondence. (He and his second wife Marga had evacuated to Rogätz in 1943 to escape the raids.) As a result, historians have only limited primary sources from which to work, and the present book does an excellent job of recounting the life and science of a man whose work laid part of the foundations of twentieth century science. - Bryson, Bill. Shakespeare. London: Harper Perennial, 2007. ISBN 978-0-00-719790-3.

- This small, thin (200 page) book contains just about every fact known for certain about the life of William Shakespeare, which isn't very much. In fact, if the book restricted itself only to those facts, and excluded descriptions of Elizabethan and Jacobean England, Shakespeare's contemporaries, actors and theatres of the time, and the many speculations about Shakespeare and the deliciously eccentric characters who sometimes promoted them, it would probably be a quarter of its present length. For a figure whose preeminence in English literature is rarely questioned today, and whose work shaped the English language itself—2035 English words appear for the first time in the works of Shakespeare, of which about 800 continue in common use today, including critical, frugal, horrid, vast, excellent, lonely, leapfrog, and zany (pp. 112–113)—very little is known apart from the content of his surviving work. We know the dates of his birth, marriage, and death, something of his parents, siblings, wife, and children, but nothing of his early life, education, travel, reading, or any of the other potential sources of the extraordinary knowledge and insight into the human psyche which informs his work. Between the years 1585 and 1592 he drops entirely from sight: no confirmed historical record has been found, then suddenly he pops up in London, at the peak of his powers, writing, producing, and performing in plays and quickly gaining recognition as one of the preeminent dramatists of his time. We don't even know (although there is no shortage of speculation) which plays were his early works and which were later: there is no documentary evidence for the dates of the plays nor the order in which they were written, apart from a few contemporary references which allow placing a play as no later than the mention of it. We don't even know how he spelt or pronounced his name: of six extant signatures believed to be in his hand, no two spell his name the same way, and none uses the “Shakespeare” spelling in use today. Shakespeare's plays brought him fame and a substantial fortune during his life, but plays were regarded as ephemeral things at the time, and were the property of the theatrical company which commissioned them, not the author, so no authoritative editions of the plays were published during his life. Had it not been for the efforts of his colleagues John Heminges and Henry Condell, who published the “First Folio” edition of his collected works seven years after his death, it is probable that the eighteen plays which first appeared in print in that edition would have been lost to history, with subsequent generations deeming Shakespeare, based upon surviving quarto editions of uneven (and sometimes laughable) quality of a few plays, one of a number of Elizabethan playwrights but not the towering singular figure he is now considered to be. (One wonders if there were others of Shakespeare's stature who were not as lucky in the dedication of their friends, of whose work we shall never know.) Nobody really knows how many copies of the First Folio were printed, but guesses run between 750 and 1000. Around 300 copies in various states of completeness have survived to the present, and around eighty copies are in a single room at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., about two blocks from the U.S. Capitol. Now maybe decades of computer disasters have made me obsessively preoccupied with backup and geographical redundancy, but that just makes me shudder. Is there anybody there who wonders whether this is really a good idea? After all, the last time I was a few blocks from the U.S. Capitol, I spotted an ACME MISSILE BOMB right in plain sight! A final chapter is devoted to theories that someone other than the scantily documented William Shakespeare wrote the works attributed to him. The author points out the historical inconsistencies and implausibilities of most frequently proffered claimants, and has a good deal of fun with some of the odder of the theorists, including the exquisitely named J. Thomas Looney, Sherwood E. Silliman, and George M. Battey. Bill Bryson fans who have come to cherish his lighthearted tone and quirky digressions on curious details and personalities from such works as A Short History of Nearly Everything (November 2007) will not be disappointed. If one leaves the book not knowing a great deal about Shakespeare, because so little is actually known, it is with a rich sense of having been immersed in the England of his time and the golden age of theatre to which he so mightily contributed. A U.S. edition is available, but at this writing only in hardcover.

- Bryson, Bill. The Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid. London: Black Swan, 2007. ISBN 978-0-552-77254-9.

-

What could be better than growing up in the United States in the

1950s? Well, perhaps being a kid with super powers

as the American dream reached its apogee and before the madness

started! In this book, humorist, travel writer, and

science populariser extraordinaire Bill Bryson

provides a memoir of his childhood (and, to a lesser extent,

coming of age) in Des Moines, Iowa in the 1950s and '60s. It is

a thoroughly engaging and charming narrative which, if you

were a kid there, then will bring back a flood of fond memories

(as well as some acutely painful ones) and if you weren't, to

appreciate, as the author closes the book, “What a wonderful

world it was. We won't see its like again, I'm afraid.”

The 1950s were the golden age of comic books, and whilst shopping

at the local supermarket, Bryson's mother would drop him in the

(unsupervised) Kiddie Corral where he and other offspring could

indulge for free to their heart's content. It's only natural

a red-blooded Iowan boy would discover himself to be a

superhero, The Thunderbolt Kid, endowed with ThunderVision, which

enabled his withering gaze to vapourise morons. Regrettably,

the power seemed to lack permanence, and the morons so dispersed

into particles of the luminiferous æther had a tedious way of

reassembling themselves and further vexing our hero and his

long-suffering schoolmates. But still, more work for

The Thunderbolt Kid!

This was a magic time in the United States—when prosperity not

only returned after depression and war, but exploded to such an extent

that mean family income more than doubled in the 1950s while most

women still remained at home raising their families. What had

been considered luxuries just a few years before: refrigerators

and freezers, cars and even second cars, single family homes, air conditioning,

television, all became commonplace (although kids would still gather

in the yard of the neighbourhood plutocrat to squint through his

window at the wonder of colour TV and chuckle at why he paid so

much for it).

Although the transformation of the U.S. from an agrarian society

to a predominantly urban and industrial nation was well underway,

most families were no more than one generation removed from the

land, and Bryson recounts his visits to his grandparents' farm

which recall what was lost and gained as that pillar of American

society went into eclipse.

There are relatively few factual errors, but from time to time Bryson's

narrative swallows counterfactual left-wing conventional

wisdom about the Fifties. For example, writing about

atomic bomb testing:

Altogether between 1946 and 1962, the United States detonated just over a thousand nuclear warheads, including some three hundred in the open air, hurling numberless tons of radioactive dust into the atmosphere. The USSR, China, Britain, and France detonated scores more.

Sigh…where do we start? Well, the obvious subtext is that U.S. started the arms race and that other nuclear powers responded in a feeble manner. In fact, the U.S. conducted a total of 1030 nuclear tests, with a total of 215 detonated in the atmosphere, including all tests up until testing was suspended in 1992, with the balance conducted underground with no release of radioactivity. The Soviet Union (USSR) did, indeed, conduct “scores” of tests, to be precise 35.75 score with a total of 715 tests, with 219 in the atmosphere—more than the U.S.—including Tsar Bomba, with a yield of 50 megatons. “Scores” indeed—surely the arms race was entirely at the instigation of the U.S. If you've grown up in he U.S. in the 1950s or wished you did, you'll want to read this book. I had totally forgotten the radioactive toilets you had to pay to use but kids could wiggle under the door to bask in their actinic glare, the glories of automobiles you could understand piece by piece and were your ticket to exploring a broad continent where every town, every city was completely different: not just another configuration of the same franchises and strip malls (and yet recall how exciting it was when they first arrived: “We're finally part of the great national adventure!”) The 1950s, when privation gave way to prosperity, yet Leviathan had not yet supplanted family, community, and civil society, it was utopia to be a kid (although, having been there, then, I'd have deemed it boring, but if I'd been confined inside as present-day embryonic taxpayers in safetyland are I'd have probably blown things up. Oh wait—Willoughby already did that, twelve hours too early!). If you grew up in the '50s, enjoy spending a few pleasant hours back there; if you're a parent of the baby boomers, exult in the childhood and opportunities you entrusted to them. And if you're a parent of a child in this constrained century? Seek to give your child the unbounded opportunities and unsupervised freedom to explore the world which Bryson and this humble scribbler experienced as we grew up. Vapourising morons with ThunderVision—we need you more than ever, Thunderbolt Kid! A U.S. edition is available. - Burns, Jennifer. Goddess of the Market. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-19-532487-7.

- For somebody who built an entire philosophical system founded on reason, and insisted that even emotion was ultimately an expression of rational thought which could be arrived at from first principles, few modern writers have inspired such passion among their readers, disciples, enemies, critics, and participants in fields ranging from literature, politics, philosophy, religion, architecture, music, economics, and human relationships as Ayn Rand. Her two principal novels, The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged (April 2010), remain among the best selling fiction titles more than half a century after their publication, with in excess of ten million copies sold. More than half a million copies of Atlas Shrugged were sold in 2009 alone. For all the commercial success of her works, which made this refugee from the Soviet Union, writing in a language she barely knew when she arrived in the United States, wealthy before her fortieth birthday, her work was generally greeted with derision among the literary establishment, reviewers in major newspapers, and academics. By the time Atlas Shrugged was published in 1957, she saw herself primarily as the founder of an all-encompassing philosophical system she named Objectivism, and her fiction as a means to demonstrate the validity of her system and communicate it to a broad audience. Academic philosophers, for the most part, did not even reject her work but simply ignored it, deeming it unworthy of their consideration. And Rand did not advance her cause by refusing to enter into the give and take of philosophical debate but instead insist that her system was self-evidently correct and had to be accepted as a package deal with no modifications. As a result, she did not so much attract followers as disciples, who looked to her words as containing the answer to all of their questions, and whose self-worth was measured by how close they became to, as it were, the fountainhead whence they sprang. Some of these people were extremely bright, and went on to distinguished careers in which they acknowledged Rand's influence on their thinking. Alan Greenspan was a member of Rand's inner circle in the 1960s, making the case for a return to the gold standard in her newsletter, before becoming the maestro of paper money decades later. Although her philosophy claimed that contradiction was impossible, her life and work were full of contradictions. While arguing that everything of value sprang from the rational creativity of free minds, she created a rigid system of thought which she insisted her followers adopt without any debate or deviation, and banished them from her circle if they dared dissent. She claimed to have created a self-consistent philosophical and moral system which was self-evidently correct, and yet she refused to debate those championing other systems. Her novels portray the state and its minions in the most starkly negative light of perhaps any broadly read fiction, and yet she detested libertarians and anarchists, defended the state as necessary to maintain the rule of law, and exulted in the success of Apollo 11 (whose launch she was invited to observe). The passion that Ayn Rand inspires has coloured most of the many investigations of her life and work published to date. Finally, in this volume, we have a more or less dispassionate examination of her career and œuvre, based on original documents in the collection of the Ayn Rand Institute and a variety of other archives. Based upon the author's Ph.D. dissertation (and with the wealth of footnotes and source citations customary in such writing), this book makes an effort to tell the story of Ayn Rand's life, work, and their impact upon politics, economics, philosophy, and culture to date, and her lasting legacy, without taking sides. The author is neither a Rand follower nor a confirmed opponent, and pretty much lets each reader decide where they come down based on the events described. At the outset, the author writes, “For over half a century, Rand has been the ultimate gateway drug to life on the right.” I initially found this very off-putting, and resigned myself to enduring another disdainful dismissal of Rand (to whose views the vast majority of the “right” over that half a century would have taken violent exception: Rand was vehemently atheist, opposing any mixing of religion and politics; a staunch supporter of abortion rights; opposed the Vietnam War and conscription; and although she rejected the legalisation of marijuana, cranked out most of her best known work while cranked on Benzedrine), as I read the book the idea began to grow on me. Indeed, many people in the libertarian and conservative worlds got their introduction to thought outside the collectivist and statist orthodoxy pervading academia and the legacy media by reading one of Ayn Rand's novels. This may have been the moment at which they first began to, as the hippies exhorted, “question authority”, and investigate other sources of information and ways of thinking and looking at the world. People who grew up with the Internet will find it almost impossible to imagine how difficult this was back in the 1960s, where even discovering the existence of a dissenting newsletter (amateurishly produced, irregularly issued, and with a tiny subscriber base) was entirely a hit or miss matter. But Ayn Rand planted the seed in the minds of millions of people, a seed which might sprout when they happened upon a like mind, or a like-minded publication. The life of Ayn Rand is simultaneously a story of an immigrant living the American dream: success in Hollywood and Broadway and wealth beyond even her vivid imagination; the frustration of an author out of tune with the ideology of the times; the political education of one who disdained politics and politicians; the birth of one of the last “big systems” of philosophy in an age where big systems had become discredited; and a life filled with passion lived by a person obsessed with reason. The author does a thorough job of pulling this all together into a comprehensible narrative which, while thoroughly documented and eschewing enthusiasm in either direction, will keep you turning the pages. The author is an academic, and writes in the contemporary scholarly idiom: the term “right-wing” appears 15 times in the book, while “left-wing” is used not at all, even when describing officials and members of the Communist Party USA. Still, this does not detract from the value of this work: a serious, in-depth, and agenda-free examination of Ayn Rand's life, work, and influence on history, today, and tomorrow.

- Carlson, W. Bernard. Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-691-16561-5.

-

Nicola Tesla was born in 1858 in a village in what is now Croatia,

then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His father and

grandfather were both priests in the Orthodox church. The family

was of Serbian descent, but had lived in Croatia since the 1690s

among a community of other Serbs. His parents wanted him to

enter the priesthood and enrolled him in school to that end. He excelled in

mathematics and, building on a boyhood fascination with machines

and tinkering, wanted to pursue a career in engineering. After

completing high school, Tesla returned to his village where he

contracted cholera and was near death. His father promised him

that if he survived, he would “go to the best technical

institution in the world.” After nine months of illness,

Tesla recovered and, in 1875 entered the Joanneum Polytechnic

School in Graz, Austria.

Tesla's university career started out brilliantly, but he came

into conflict with one of his physics professors over the

feasibility of designing a motor which would operate without

the troublesome and unreliable commutator and brushes of

existing motors. He became addicted to

gambling, lost his scholarship, and dropped out in his third

year. He worked as a draftsman, taught in his old high school,

and eventually ended up in Prague, intending to continue his

study of engineering at the Karl-Ferdinand University. He

took a variety of courses, but eventually his uncles withdrew

their financial support.

Tesla then moved to Budapest, where he found employment as

chief electrician at the Budapest Telephone Exchange. He

quickly distinguished himself as a problem solver and innovator and,

before long, came to the attention of the Continental Edison Company

of France, which had designed the equipment used in Budapest. He

was offered and accepted a job at their headquarters in

Ivry, France. Most of Edison's employees had practical, hands-on

experience with electrical equipment, but lacked Tesla's

formal education in mathematics and physics. Before long, Tesla

was designing dynamos for lighting plants and earning a

handsome salary. With his language skills (by that time, Tesla

was fluent in Serbian, German, and French, and was improving his

English), the Edison company sent him into the field as a

trouble-shooter. This further increased his reputation and,

in 1884 he was offered a job at Edison headquarters in New York.

He arrived and, years later, described the formalities of

entering the U.S. as an immigrant: a clerk saying “Kiss

the Bible. Twenty cents!”.

Tesla had never abandoned the idea of a brushless motor. Almost

all electric lighting systems in the 1880s used

direct current (DC):

electrons flowed in only one direction through the distribution

wires. This is the kind of current produced by batteries,

and the first electrical generators (dynamos) produced direct

current by means of a device called a

commutator.

As the generator is turned by its power source (for example, a steam

engine or water wheel), power is extracted from the rotating commutator

by fixed brushes which press against it. The contacts on the

commutator are wired to the coils in the generator in such a way

that a constant direct current is maintained. When direct current

is used to drive a motor, the motor must also contain a commutator

which converts the direct current into a reversing flow to maintain

the motor in rotary motion.

Commutators, with brushes rubbing against them, are inefficient

and unreliable. Brushes wear and must eventually be replaced, and

as the commutator rotates and the brushes make and break contact,

sparks may be produced which waste energy and degrade the

contacts. Further, direct current has a major disadvantage

for long-distance power transmission. There was, at the time,

no way to efficiently change the voltage of direct current. This

meant that the circuit from the generator to the user of the

power had to run at the same voltage the user received,

say 120 volts. But at such a voltage, resistance losses in

copper wires are such that over long runs most of the energy

would be lost in the wires, not delivered to customers. You can

increase the size of the distribution wires to reduce losses, but

before long this becomes impractical due to the cost of copper

it would require. As a consequence, Edison

electric lighting systems installed in the 19th century had

many small powerhouses, each supplying a local set of

customers.

Alternating

current (AC) solves the problem of power distribution. In 1881

the electrical transformer had been invented, and by 1884

high-efficiency transformers were being manufactured in Europe.

Powered by alternating current (they don't work with DC),

a transformer efficiently converts current from one voltage and current to

another. For example, power might be transmitted from the generating

station to the customer at 12000 volts and 1 ampere, then stepped

down to 120 volts and 100 amperes by a transformer at the customer

location. Losses in a wire are purely a function of current, not

voltage, so for a given level of transmission loss, the cables

to distribute power at 12000 volts will cost a hundredth as

much as if 120 volts were used. For electric lighting,

alternating current works just as well as direct current (as

long as the frequency of the alternating current is sufficiently

high that lamps do not flicker). But electricity was increasingly

used to power motors, replacing steam power in factories. All

existing practical motors ran on DC, so this was seen as an

advantage to Edison's system.

Tesla worked only six months for Edison. After developing an

arc lighting system only to have Edison put it on the shelf

after acquiring the rights to a system developed by another

company, he quit in disgust. He then continued to work on

an arc light system in New Jersey, but the company to which

he had licensed his patents failed, leaving him only with a

worthless stock certificate. To support himself, Tesla worked

repairing electrical equipment and even digging ditches, where

one of his foremen introduced him to Alfred S. Brown, who

had made his career in telegraphy. Tesla showed Brown one

of his patents, for a “thermomagnetic motor”, and

Brown contacted Charles F. Peck, a lawyer who had made his

fortune in telegraphy. Together, Peck and Brown saw the

potential for the motor and other Tesla inventions and in

April 1887 founded the Tesla Electric Company, with its

laboratory in Manhattan's financial district.

Tesla immediately set to make his dream of a brushless AC motor a

practical reality and, by using multiple AC currents, out of phase with

one another (the

polyphase system),

he was able to create a magnetic field which itself

rotated. The rotating magnetic field induced a current in the

rotating part of the motor, which would start and turn

without any need for a commutator or brushes.

Tesla had invented what we now call the

induction motor.

He began to file patent applications for the motor and the

polyphase AC transmission system in the fall of 1887, and by

May of the following year had been granted a total of seven

patents on various aspects of the motor and polyphase current.

One disadvantage of the polyphase system and motor was that it required

multiple pairs of wires to transmit power from the generator to the

motor, which increased cost and complexity. Also,

existing AC lighting systems, which were beginning to come into use,

primarily in Europe, used a single phase and two wires. Tesla

invented the

split-phase motor,

which would run on a two wire, single phase circuit, and this was

quickly patented.

Unlike Edison, who had built an industrial empire based upon

his inventions, Tesla, Peck, and Brown had no interest in

founding a company to manufacture Tesla's motors. Instead,

they intended to shop around and license the patents to an

existing enterprise with the resources required to exploit

them. George Westinghouse had developed his inventions of

air brakes and signalling systems for railways into a

successful and growing company, and was beginning to compete

with Edison in the electric light industry, installing AC

systems. Westinghouse was a prime prospect to license the

patents, and in July 1888 a deal was concluded for cash,

notes, and a royalty for each horsepower of motors sold.

Tesla moved to Pittsburgh, where he spent a year working in

the Westinghouse research lab improving the motor designs.

While there, he filed an additional fifteen patent applications.

After leaving Westinghouse, Tesla took a trip to Europe

where he became fascinated with Heinrich Hertz's discovery

of electromagnetic waves. Produced by alternating current at

frequencies much higher than those used in electrical power

systems (Hertz used a spark gap to produce them), here was

a demonstration of transmission of electricity through

thin air—with no wires at all. This idea was to

inspire much of Tesla's work for the rest of his life.

By 1891, he had invented a resonant high frequency

transformer which we now call a

Tesla coil,

and before long was performing spectacular demonstrations

of artificial lightning, illuminating lamps at a distance

without wires, and demonstrating new kinds of electric lights

far more efficient than Edison's incandescent bulbs.

Tesla's reputation as an inventor was equalled by his

talent as a showman in presentations before scientific

societies and the public in both the U.S. and Europe.

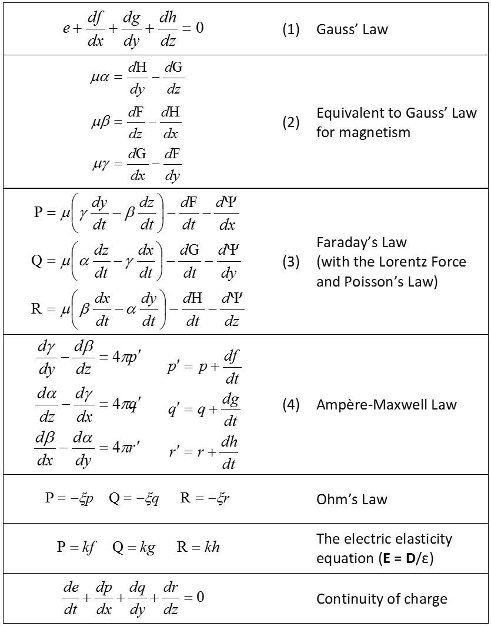

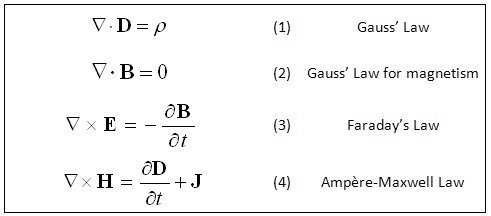

Oddly, for someone with Tesla's academic and practical background,

there is no evidence that he mastered Maxwell's theory of

electromagnetism. He believed that the phenomena he observed

with the Tesla coil and other apparatus were not due to the

Hertzian waves predicted by Maxwell's equations, but rather

something he called “electrostatic thrusts”. He

was later to build a great edifice of mistaken theory on this

crackpot idea.

By 1892, plans were progressing to harness the hydroelectric

power of Niagara Falls. Transmission of this power

to customers was central to the project: around one

fifth of the American population lived within 400 miles

of the falls. Westinghouse bid Tesla's polyphase

system and with Tesla's help in persuading the committee

charged with evaluating proposals, was awarded the contract

in 1893. By November of 1896, power from Niagara reached

Buffalo, twenty miles away, and over the next decade extended

throughout New York. The success of the project made polyphase

power transmission the technology of choice for most

electrical distribution systems, and it remains so to this day.

In 1895, the New York Times wrote:

Even now, the world is more apt to think of him as a producer of weird experimental effects than as a practical and useful inventor. Not so the scientific public or the business men. By the latter classes Tesla is properly appreciated, honored, perhaps even envied. For he has given to the world a complete solution of the problem which has taxed the brains and occupied the time of the greatest electro-scientists for the last two decades—namely, the successful adaptation of electrical power transmitted over long distances.

After the Niagara project, Tesla continued to invent, demonstrate his work, and obtain patents. With the support of patrons such as John Jacob Astor and J. P. Morgan he pursued his work on wireless transmission of power at laboratories in Colorado Springs and Wardenclyffe on Long Island. He continued to be featured in the popular press, amplifying his public image as an eccentric genius and mad scientist. Tesla lived until 1943, dying at the age of 86 of a heart attack. Over his life, he obtained around 300 patents for devices as varied as a new form of turbine, a radio controlled boat, and a vertical takeoff and landing airplane. He speculated about wireless worldwide distribution of news to personal mobile devices and directed energy weapons to defeat the threat of bombers. While in Colorado, he believed he had detected signals from extraterrestrial beings. In his experiments with high voltage, he accidently detected X-rays before Röntgen announced their discovery, but he didn't understand what he had observed. None of these inventions had any practical consequences. The centrepiece of Tesla's post-Niagara work, the wireless transmission of power, was based upon a flawed theory of how electricity interacts with the Earth. Tesla believed that the Earth was filled with electricity and that if he pumped electricity into it at one point, a resonant receiver anywhere else on the Earth could extract it, just as if you pump air into a soccer ball, it can be drained out by a tap elsewhere on the ball. This is, of course, complete nonsense, as his contemporaries working in the field knew, and said, at the time. While Tesla continued to garner popular press coverage for his increasingly bizarre theories, he was ignored by those who understood they could never work. Undeterred, Tesla proceeded to build an enormous prototype of his transmitter at Wardenclyffe, intended to span the Atlantic, without ever, for example, constructing a smaller-scale facility to verify his theories over a distance of, say, ten miles. Tesla's invention of polyphase current distribution and the induction motor were central to the electrification of nations and continue to be used today. His subsequent work was increasingly unmoored from the growing theoretical understanding of electromagnetism and many of his ideas could not have worked. The turbine worked, but was uncompetitive with the fabrication and materials of the time. The radio controlled boat was clever, but was far from the magic bullet to defeat the threat of the battleship he claimed it to be. The particle beam weapon (death ray) was a fantasy. In recent decades, Tesla has become a magnet for Internet-connected crackpots, who have woven elaborate fantasies around his work. Finally, in this book, written by a historian of engineering and based upon original sources, we have an authoritative and unbiased look at Tesla's life, his inventions, and their impact upon society. You will understand not only what Tesla invented, but why, and how the inventions worked. The flaky aspects of his life are here as well, but never mocked; inventors have to think ahead of accepted knowledge, and sometimes they will inevitably get things wrong. - Carpenter, [Malcolm] Scott and Kris Stoever. For Spacious Skies. New York: Harcourt, 2002. ISBN 0-15-100467-6.

- This is the most detailed, candid, and well-documented astronaut memoir I've read (Collins' Carrying the Fire is a close second). Included is a pointed riposte to “the man malfunctioned” interpretation of Carpenter's MA-7 mission given in Chris Kraft's autobiography Flight (May 2001). Co-author Stoever is Carpenter's daughter.

- Chaikin, Andrew. John Glenn: America's Astronaut. Washington: Smithsonian Books, 2014. ISBN 978-1-58834-486-1.

- This short book (around 126 pages print equivalent), available only for the Kindle as a “Kindle single” at a modest price, chronicles the life and space missions of the first American to orbit the Earth. John Glenn grew up in a small Ohio town, the son of a plumber, and matured during the first great depression. His course in life was set when, in 1929, his father took his eight year old son on a joy ride offered by a pilot at local airfield in a Waco biplane. After that, Glenn filled up his room with model airplanes, intently followed news of air racers and pioneers of exploration by air, and in 1938 attended the Cleveland Air Races. There seemed little hope of his achieving his dream of becoming an airman himself: pilot training was expensive, and his family, while making ends meet during the depression, couldn't afford such a luxury. With the war in Europe underway and the U.S. beginning to rearm and prepare for possible hostilities, Glenn heard of a government program, the Civilian Pilot Training Program, which would pay for his flying lessons and give him college credit for taking them. He entered the program immediately and received his pilot's license in May 1942. By then, the world was a very different place. Glenn dropped out of college in his junior year and applied for the Army Air Corps. When they dawdled accepting him, he volunteered for the Navy, which immediately sent him to flight school. After completing advanced flight training, he transferred to the Marine Corps, which was seeking aviators. Sent to the South Pacific theatre, he flew 59 combat missions, mostly in close air support of ground troops in which Marine pilots specialise. With the end of the war, he decided to make the Marines his career and rotated through a number of stateside posts. After the outbreak of the Korean War, he hoped to see action in the jet combat emerging there and in 1953 arrived in country, again flying close air support. But an exchange program with the Air Force finally allowed him to achieve his ambition of engaging in air to air combat at ten miles a minute. He completed 90 combat missions in Korea, and emerged as one of the Marine Corps' most distinguished pilots. Glenn parlayed his combat record into a test pilot position, which allowed him to fly the newest and hottest aircraft of the Navy and Marines. When NASA went looking for pilots for its Mercury manned spaceflight program, Glenn was naturally near the top of the list, and was among the 110 military test pilots invited to the top secret briefing about the project. Despite not meeting all of the formal selection criteria (he lacked a college degree), he performed superbly in all of the harrowing tests to which candidates were subjected, made cut after cut, and was among the seven selected to be the first astronauts. This book, with copious illustrations and two embedded videos, chronicles Glenn's career, his harrowing first flight into space, his 1998 return to space on Space Shuttle Discovery on STS-95, and his 24 year stint in the U.S. Senate. I found the picture of Glenn after his pioneering flight somewhat airbrushed. It is said that while in the Senate, “He was known as one of NASA's strongest supporters on Capitol Hill…”, and yet in fact, while not one of the rabid Democrats who tried to kill NASA like Walter Mondale, he did not speak out as an advocate for a more aggressive space program aimed at expanding the human presence in space. His return to space is presented as the result of his assiduously promoting the benefits of space research for gerontology rather than a political junket by a senator which would generate publicity for NASA at a time when many people had tuned out its routine missions. (And if there was so much to be learned by flying elderly people in space, why was it never done again?) John Glenn was a quintessential product of the old, tough America. A hero in two wars, test pilot when that was one of the most risky of occupations, and first to ride the thin-skinned pressure-stabilised Atlas rocket into orbit, his place in history is assured. His subsequent career as a politician was not particularly distinguished: he initiated few pieces of significant legislation and never became a figure on the national stage. His campaign for the 1984 Democratic presidential nomination went nowhere, and he was implicated in the “Keating Five” scandal. John Glenn accomplished enough in the first forty-five years of his life to earn him a secure place in American history. This book does an excellent job of recounting those events and placing them in the context of the time. If it goes a bit too far in lionising his subsequent career, that's understandable: a biographer shouldn't always succumb to balance when dealing with a hero.

- Chambers, Whittaker. Witness. Washington: Regnery Publishing, [1952] 2002. ISBN 0-89526-789-6.

- Chertok, Boris E. Rockets and People. Vol. 1. Washington: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, [1999] 2005. ISBN 978-1-4700-1463-6 NASA SP-2005-4110.

- This is the first book of the author's monumental four-volume autobiographical history of the Soviet missile and space program. Boris Chertok was a survivor, living through the Bolshevik revolution, Stalin's purges of the 1930s, World War II, all of the postwar conflict between chief designers and their bureaux and rival politicians, and the collapse of the Soviet Union. Born in Poland in 1912, he died in 2011 in Moscow. After retiring from the RKK Energia organisation in 1992 at the age of 80, he wrote this work between 1994 and 1999. Originally published in Russian in 1999, this annotated English translation was prepared by the NASA History Office under the direction of Asif A. Siddiqi, author of Challenge to Apollo (April 2008), the definitive Western history of the Soviet space program. Chertok saw it all, from the earliest Soviet experiments with rocketry in the 1930s, uncovering the secrets of the German V-2 amid the rubble of postwar Germany (he was the director of the Institute RABE, where German and Soviet specialists worked side by side laying the foundations of postwar Soviet rocketry), the glory days of Sputnik and Gagarin, the anguish of losing the Moon race, and the emergence of Soviet preeminence in long-duration space station operations. The first volume covers Chertok's career up to the conclusion of his work in Germany in 1947. Unlike Challenge to Apollo, which is a scholarly institutional and technical history (and consequently rather dry reading), Chertok gives you a visceral sense of what it was like to be there: sometimes chilling, as in his descriptions of the 1930s where he matter-of-factly describes his supervisors and colleagues as having been shot or sent to Siberia just as an employee in the West would speak of somebody being transferred to another office, and occasionally funny, as when he recounts the story of the imperious Valentin Glushko showing up at his door in a car belching copious smoke. It turns out that Glushko had driven all the way with the handbrake on, and his subordinate hadn't dared mention it because Glushko didn't like to be distracted when at the wheel. When the Soviets began to roll out their space spectaculars in the late 1950s and early '60s, some in the West attributed their success to the Soviets having gotten the “good German” rocket scientists while the West ended up with the second team. Chertok's memoir puts an end to such speculation. By the time the Americans and British vacated the V-2 production areas, they had packed up and shipped out hundreds of rail cars of V-2 missiles and components and captured von Braun and all of his senior staff, who delivered extensive technical documentation as part of their surrender. This left the Soviets with pretty slim pickings, and Chertok and his staff struggled to find components, documents, and specialists left behind. This put them at a substantial disadvantage compared to the U.S., but forced them to reverse-engineer German technology and train their own people in the disciplines of guided missilery rather than rely upon a German rocket team. History owes a great debt to Boris Chertok not only for the achievements in his six decade career (for which he was awarded Hero of Socialist Labour, the Lenin Prize, the Order of Lenin [twice], and the USSR State Prize), but for living so long and undertaking to document the momentous events he experienced at the first epoch at which such a candid account was possible. Only after the fall of the Soviet Union could the events chronicled here be freely discussed, and the merits and shortcomings of the Soviet system in accomplishing large technological projects be weighed. As with all NASA publications, the work is in the public domain, and an online PDF edition is available. A Kindle edition is available which is perfectly readable but rather cheaply produced. Footnotes simply appear in the text in-line somewhere after the reference, set in small red type. Words are occasionally run together and capitalisation is missing on some proper nouns. The index references page numbers from the print edition which are not included in the Kindle version, and hence are completely useless. If you have a workable PDF application on your reading device, I'd go with the NASA PDF, which is not only better formatted but free. The original Russian edition is available online.

- Chertok, Boris E. Rockets and People. Vol. 2. Washington: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, [1999] 2006. ISBN 978-1-4700-1508-4 NASA SP-2006-4110.

- This is the second book of the author's four-volume autobiographical history of the Soviet missile and space program. Boris Chertok was a survivor, living through the Bolshevik revolution, the Russian civil war, Stalin's purges of the 1930s, World War II, all of the postwar conflict between chief designers and their bureaux and rival politicians, and the collapse of the Soviet Union. Born in Poland in 1912, he died in 2011 in Moscow. After retiring from the RKK Energia organisation in 1992 at the age of 80, he wrote this work between 1994 and 1999. Originally published in Russian in 1999, this annotated English translation was prepared by the NASA History Office under the direction of Asif A. Siddiqi, author of Challenge to Apollo (April 2008), the definitive Western history of the Soviet space program. Volume 2 of Chertok's chronicle begins with his return from Germany to the Soviet Union, where he discovers, to his dismay, that day-to-day life in the victorious workers' state is much harder than in the land of the defeated fascist enemy. He becomes part of the project, mandated by Stalin, to first launch captured German V-2 missiles and then produce an exact Soviet copy, designated the R-1. Chertok and his colleagues discover that making a copy of foreign technology may be more difficult than developing it from scratch—the V-2 used a multitude of steel and non-ferrous metal alloys, as well as numerous non-metallic components (seals, gaskets, insulation, etc.) which were not produced by Soviet industry. But without the experience of the German rocket team (which, by this time, was in the United States), there was no way to know whether the choice of a particular material was because its properties were essential to its function or simply because it was readily available in Germany. Thus, making an “exact copy” involved numerous difficult judgement calls where the designers had to weigh the risk of deviation from the German design against the cost of standing up a Soviet manufacturing capacity which might prove unnecessary. After the difficult start which is the rule for missile projects, the Soviets managed to turn the R-1 into a reliable missile and, through patience and painstaking analysis of telemetry, solved a mystery which had baffled the Germans: why between 10% and 20% of V-2 warheads had detonated in a useless airburst high above the intended target. Chertok's instrumentation proved that the cause was aerodynamic heating during re-entry which caused the high explosive warhead to outgas, deform, and trigger the detonator. As the Soviet missile program progresses, Chertok is a key player, participating in the follow-on R-2 project (essentially a Soviet Redstone—a V-2 derivative, but entirely of domestic design), the R-5 (an intermediate range ballistic missile eventually armed with nuclear warheads), and the R-7, the world's first intercontinental ballistic missile, which launched Sputnik, Gagarin, and whose derivatives remain in service today, providing the only crewed access to the International Space Station as of this writing. Not only did the Soviet engineers have to build ever larger and more complicated hardware, they essentially had to invent the discipline of systems engineering all by themselves. While even in aviation it is often possible to test components in isolation and then integrate them into a vehicle, working out interface problems as they manifest themselves, in rocketry everything interacts, and when something goes wrong, you have only the telemetry and wreckage upon which to base your diagnosis. Consider: a rocket ascending may have natural frequencies in its tankage structure excited by vibration due to combustion instabilities in the engine. This can, in turn, cause propellant delivery to the engine to oscillate, which will cause pulses in thrust, which can cause further structural stress. These excursions may cause control actuators to be over-stressed and possibly fail. When all you have to go on is a ragged cloud in the sky, bits of metal raining down on the launch site, and some telemetry squiggles for a second or two before everything went pear shaped, it can be extraordinarily difficult to figure out what went wrong. And none of this can be tested on the ground. Only a complete systems approach can begin to cope with problems like this, and building that kind of organisation required a profound change in Soviet institutions, which had previously been built around imperial chief designers with highly specialised missions. When everything interacts, you need a different structure, and it was part of the genius of Sergei Korolev to create it. (Korolev, who was the author's boss for most of the years described here, is rightly celebrated as a great engineer and champion of missile and space projects, but in Chertok's view at least equally important was his talent in quickly evaluating the potential of individuals and filling jobs with the people [often improbable candidates] best able to do them.) In this book we see the transformation of the Soviet missile program from slavishly copying German technology to world-class innovation, producing, in short order, the first ICBM, earth satellite, lunar impact, images of the lunar far side, and interplanetary probes. The missile men found themselves vaulted from an obscure adjunct of Red Army artillery to the vanguard of Soviet prestige in the world, with the Soviet leadership urging them on to ever greater exploits. There is a tremendous amount of detail here—so much that some readers have deemed it tedious: I found it enlightening. The author dissects the Nedelin disaster in forensic detail, as well as the much less known 1980 catastrophe at Plesetsk where 48 died because a component of the rocket used the wrong kind of solder. Rocketry is an exacting business, and it is a gift to generations about to embark upon it to imbibe the wisdom of one who was present at its creation and learned, by decades of experience, just how careful one must be to succeed at it. I could go on regaling you with anecdotes from this book but, hey, if you've made it this far, you're probably going to read it yourself, so what's the point? (But if you do, I'd suggest you read Volume 1 [May 2012] first.) As with all NASA publications, the work is in the public domain, and an online PDF edition is available. A Kindle edition is available which is perfectly readable but rather cheaply produced. Footnotes simply appear in the text in-line somewhere after the reference, set in small red type. The index references page numbers from the print edition which are not included in the Kindle version, and hence are completely useless. If you have a workable PDF application on your reading device, I'd go with the NASA PDF, which is not only better formatted but free. The original Russian edition is available online.

- Chertok, Boris E. Rockets and People. Vol. 3. Washington: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, [1999] 2009. ISBN 978-1-4700-1437-7 NASA SP-2009-4110.

- This is the third book of the author's four-volume autobiographical history of the Soviet missile and space program. Boris Chertok was a survivor, living through the Bolshevik revolution, the Russian civil war, Stalin's purges of the 1930s, World War II, all of the postwar conflict between chief designers and their bureaux and rival politicians, and the collapse of the Soviet Union. Born in Poland in 1912, he died in 2011 in Moscow. After retiring from the RKK Energia organisation in 1992 at the age of 80, he wrote this work between 1994 and 1999. Originally published in Russian in 1999, this annotated English translation was prepared by the NASA History Office under the direction of Asif A. Siddiqi, author of Challenge to Apollo (April 2008), the definitive Western history of the Soviet space program. Volume 2 of this memoir chronicled the achievements which thrust the Soviet Union's missile and space program into the consciousness of people world-wide and sparked the space race with the United States: the development of the R-7 ICBM, Sputnik and its successors, and the first flights which photographed the far side of the Moon and impacted on its surface. In this volume, the author describes the projects and accomplishments which built upon this base and persuaded many observers of the supremacy of Soviet space technology. Since the author's speciality was control systems and radio technology, he had an almost unique perspective upon these events: unlike other designers who focussed upon one or a few projects, he was involved in almost all of the principal efforts, from intermediate range, intercontinental, and submarine-launched ballistic missiles; air and anti-missile defence; piloted spaceflight; reconnaissance, weather, and navigation satellites; communication satellites; deep space missions and the ground support for them; soft landing on the Moon; and automatic rendezvous and docking. He was present when it looked like the rudimentary R-7 ICBM might be launched in anger during the Cuban missile crisis, at the table as chief designers battled over whether combat missiles should use cryogenic or storable liquid propellants or solid fuel, and sat on endless boards of inquiry after mission failures—the first eleven attempts to soft-land on the Moon failed, and Chertok was there for each launch, subsequent tracking, and sorting through what went wrong. This was a time of triumph for the Soviet space program: the first manned flight, endurance record after endurance record, dual flights, the first woman in space, the first flight with a crew of more than one, and the first spacewalk. But from Chertok's perspective inside the programs, and the freedom he had to write candidly in the 1990s about his experiences, it is clear that the seeds of tragedy were being sown. With the quest for one spectacular after another, each surpassing the last, the Soviets became inoculated with what NASA came to call “go fever”—a willingness to brush anomalies under the rug and normalise the abnormal because you'd gotten away with it before. One of the most stunning examples of this is Gagarin's flight. The Vostok spacecraft consisted of a spherical descent module (basically a cannonball covered with ablative thermal protection material) and an instrument compartment containing the retro-rocket, attitude control system, and antennas. After firing the retro-rocket, the instrument compartment was supposed to separate, allowing the descent module's heat shield to protect it through atmospheric re-entry. (The Vostok performed a purely ballistic re-entry, and had no attitude control thrusters in the descent module; stability was maintained exclusively by an offset centre of gravity.) In the two unmanned test flights which preceded Garagin's mission, the instrument module had failed to cleanly separate from the descent module, but the connection burned through during re-entry and the descent module survived. Gagarin was launched in a spacecraft with the same design, and the same thing happened: there were wild oscillations, but after the link burned through his spacecraft stabilised. Astonishingly, Vostok 2 was launched with Gherman Titov on board with precisely the same flaw, and suffered the same failure during re-entry. Once again, the cosmonaut won this orbital game of Russian roulette. One wonders what lessons were learned from this. In this narrative, Chertok is simply aghast at the decision making here, but one gets the sense that you had to be there, then, to appreciate what was going through people's heads. The author was extensively involved in the development of the first Soviet communications satellite, Molniya, and provides extensive insights into its design, testing, and early operations. It is often said that the Molniya orbit was chosen because it made the satellite visible from the Soviet far North where geostationary satellites would be too close to the horizon for reliable communication. It is certainly true that today this orbit continues to be used for communications with Russian arctic territories, but its adoption for the first Soviet communications satellite had an entirely different motivation. Due to the high latitude of the Soviet launch site in Kazakhstan, Korolev's R-7 derived booster could place only about 100 kilograms into a geostationary orbit, which was far too little for a communication satellite with the technology of the time, but it could loft 1,600 kilograms into a high-inclination Molniya orbit. The only alternative would have been for Korolev to have approached Chelomey to launch a geostationary satellite on his UR-500 (Proton) booster, which was unthinkable because at the time the two were bitter rivals. So much for the frictionless efficiency of central planning! In engineering, one learns that every corner cut will eventually come back to cut you. Korolev died at just the time he was most needed by the Soviet space program due to a botched operation for a routine condition performed by a surgeon who had spent most of his time as a Minister of the Soviet Union and not in the operating room. Gagarin died in a jet fighter training accident which has been the subject of such an extensive and multi-layered cover-up and spin that the author simply cites various accounts and leaves it to the reader to judge. Komarov died in Soyuz 1 due to a parachute problem which would have been discovered had an unmanned flight preceded his. He was a victim of “go fever”. There is so much insight and wisdom here I cannot possibly summarise it all; you'll have to read this book to fully appreciate it, ideally after having first read Volume 1 (May 2012) and Volume 2 (August 2012). Apart from the unique insider's perspective on the Soviet missile and space program, as a person elected a corresponding member of the Soviet Academy of Sciences in 1968 and a full member (academician) of the Russian Academy of Sciences in 2000, he provides a candid view of the politics of selection of members of the Academy and how they influence policy and projects at the national level. Chertok believes that, even as one who survived Stalin's purges, there were merits to the Soviet system which have been lost in the “new Russia”. His observations are worth pondering by those who instinctively believe the market will always converge upon the optimal solution. As with all NASA publications, the work is in the public domain, and an online edition in PDF, EPUB, and MOBI formats is available. A commercial Kindle edition is available which is perfectly readable but rather cheaply produced. Footnotes simply appear in the text in-line somewhere after the reference, set in small red type. The index references page numbers from the print edition which are not included in the Kindle version, and hence are completely useless. If you have a suitable application on your reading device for one of the electronic book formats provided by NASA, I'd opt for it. They are not only better formatted but free. The original Russian edition is available online.

- Chertok, Boris E. Rockets and People. Vol. 4. Washington: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, [1999] 2011. ISBN 978-1-4700-1437-7 NASA SP-2011-4110.

-

This is the fourth and final book of the author's

autobiographical history of the Soviet missile

and space program.

Boris Chertok

was a survivor, living through the Bolshevik revolution, the Russian

civil war, Stalin's purges of the 1930s, World War II, all of the

postwar conflict between chief designers and their bureaux and rival

politicians, and the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Born in Poland in

1912, he died in 2011 in Moscow. As he says in this volume,

“I was born in the Russian Empire, grew up in Soviet Russia,

achieved a great deal in the Soviet Union, and continue to work in

Russia.”

After retiring from the RKK Energia

organisation in 1992 at the age of 80, he wrote this work between 1994

and 1999. Originally published in Russian in 1999, this annotated

English translation was prepared by the NASA History Office under the

direction of Asif A. Siddiqi, author of

Challenge to Apollo (April 2008),

the definitive Western history of the Soviet space

program.

This work covers the Soviet manned lunar program and the development

of long-duration space stations and orbital rendezvous, docking,

and assembly. As always, Chertok was there, and

participated in design and testing, was present for launches

and in the control centre during flights, and all too often

participated in accident investigations.

In retrospect, the Soviet manned lunar program seems almost

bizarre. It did not begin in earnest until two years after

NASA's Apollo program was underway, and while the Gemini

and Apollo programs were a step-by-step process of developing

and proving the technologies and operational experience for

lunar missions, the Soviet program was a chaotic bag of elements

seemingly driven more by the rivalries of the various chief

designers than a coherent plan for getting to the Moon.

First of all, there were two manned lunar programs,

each using entirely different hardware and mission profiles.

The Zond

program used a modified Soyuz spacecraft launched on a

Proton

booster, intended to send two cosmonauts on a

circumlunar mission. They would simply loop around the Moon

and return to Earth without going into orbit. A total of

eight of these missions were launched unmanned, and only one

completed a flight which would have been safe for cosmonauts

on board. After

Apollo 8

accomplished a much more ambitious lunar orbital mission in

December 1968, a Zond flight would simply demonstrate how

far behind the Soviets were, and the program was cancelled

in 1970.

The N1-L3

manned lunar landing program was even more curious. In the

Apollo program, the choice of mission mode and determination

of mass required for the lunar craft came first, and the

specifications of the booster rocket followed from that.

Work on

Korolev's

N1 heavy lifter did not get underway until 1965—four years

after the Saturn V, and it was envisioned as a general purpose

booster for a variety of military and civil space missions.

Korolev wanted to use very high thrust kerosene engines on the

first stage and hydrogen engines on the upper stages as did

the Saturn V, but he was involved in a feud with

Valentin Glushko,

who championed the use of hypergolic, high boiling point, toxic

propellants and refused to work on the engines Korolev requested.

Hydrogen propellant technology in the Soviet Union

was in its infancy at the time, and Korolev realised that waiting

for it to mature would add years to the schedule.

In need of engines, Korolev approached

Nikolai Kuznetsov,

a celebrated designer of jet turbine engines, but who had no

previous experience at all with rocket engines. Kuznetsov's

engines were much smaller than Korolev desired, and to obtain