- Brown, Brandon R. Planck. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-021947-5.

-

Theoretical physics is usually a young person's game. Many of the

greatest breakthroughs have been made by researchers in their

twenties, just having mastered existing theories while remaining

intellectually flexible and open to new ideas. Max Planck,

born in 1858, was an exception to this rule. He spent most of his

twenties living with his parents and despairing of finding a

paid position in academia. He was thirty-six when he took on

the project of understanding heat radiation, and forty-two

when he explained it in terms which would launch the quantum

revolution in physics. He was in his fifties when he discovered

the zero-point energy of the vacuum, and remained engaged and active

in science until shortly before his death in 1947 at the age of

89. As theoretical physics editor for the then most

prestigious physics journal in the world,

Annalen der Physik, in 1905 he

approved publication of Einstein's special theory of relativity,

embraced the new ideas from a young outsider with neither a Ph.D. nor

an academic position, extended the theory in his own work in

subsequent years, and was instrumental in persuading Einstein

to come to Berlin, where he became a close friend.

Sometimes the simplest puzzles lead to the most profound of insights.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the radiation emitted by

heated bodies was such a conundrum. All objects emit electromagnetic

radiation due to the thermal motion of their molecules. If an object

is sufficiently hot, such as the filament of an incandescent lamp or

the surface of the Sun, some of the radiation will fall into the

visible range and be perceived as light. Cooler objects emit in

the infrared or lower frequency bands and can be detected by

instruments sensitive to them. The radiation emitted by a hot

object has a characteristic spectrum (the distribution of energy

by frequency), and has a peak which depends only upon the

temperature of the body. One of the simplest cases is that of a

black body,

an ideal object which perfectly absorbs all incident radiation.

Consider an ideal closed oven which loses no heat to the outside.

When heated to a given temperature, its walls will absorb and

re-emit radiation, with the spectrum depending upon its temperature.

But the

equipartition

theorem, a cornerstone of

statistical

mechanics, predicted that the absorption and re-emission of

radiation in the closed oven would result in a ever-increasing

peak frequency and energy, diverging to infinite temperature, the

so-called

ultraviolet

catastrophe. Not only did this violate the law of conservation of

energy, it was an affront to common sense: closed ovens do not explode

like nuclear bombs. And yet the theory which predicted this behaviour,

the

Rayleigh-Jeans

law,

made perfect sense based upon the motion of atoms and molecules,

correctly predicted numerous physical phenomena, and was correct for

thermal radiation at lower temperatures.

At the time Planck took up the problem of thermal radiation,

experimenters in Germany were engaged in measuring the radiation

emitted by hot objects with ever-increasing precision, confirming

the discrepancy between theory and reality, and falsifying several

attempts to explain the measurements. In December 1900, Planck

presented his new theory of black body radiation and what is

now called

Planck's Law

at a conference in Berlin. Written in modern notation, his

formula for the energy emitted by a body of temperature

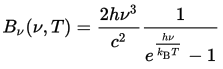

T at frequency ν is:

This equation not only correctly predicted the results measured in the laboratories, it avoided the ultraviolet catastrophe, as it predicted an absolute cutoff of the highest frequency radiation which could be emitted based upon an object's temperature. This meant that the absorption and re-emission of radiation in the closed oven could never run away to infinity because no energy could be emitted above the limit imposed by the temperature. Fine: the theory explained the measurements. But what did it mean? More than a century later, we're still trying to figure that out. Planck modeled the walls of the oven as a series of resonators, but unlike earlier theories in which each could emit energy at any frequency, he constrained them to produce discrete chunks of energy with a value determined by the frequency emitted. This had the result of imposing a limit on the frequency due to the available energy. While this assumption yielded the correct result, Planck, deeply steeped in the nineteenth century tradition of the continuum, did not initially suggest that energy was actually emitted in discrete packets, considering this aspect of his theory “a purely formal assumption.” Planck's 1900 paper generated little reaction: it was observed to fit the data, but the theory and its implications went over the heads of most physicists. In 1905, in his capacity as editor of Annalen der Physik, he read and approved the publication of Einstein's paper on the photoelectric effect, which explained another physics puzzle by assuming that light was actually emitted in discrete bundles with an energy determined by its frequency. But Planck, whose equation manifested the same property, wasn't ready to go that far. As late as 1913, he wrote of Einstein, “That he might sometimes have overshot the target in his speculations, as for example in his light quantum hypothesis, should not be counted against him too much.” Only in the 1920s did Planck fully accept the implications of his work as embodied in the emerging quantum theory.

The equation for Planck's Law contained two new fundamental physical constants: Planck's constant (h) and Boltzmann's constant (kB). (Boltzmann's constant was named in memory of Ludwig Boltzmann, the pioneer of statistical mechanics, who committed suicide in 1906. The constant was first introduced by Planck in his theory of thermal radiation.) Planck realised that these new constants, which related the worlds of the very large and very small, together with other physical constants such as the speed of light (c), the gravitational constant (G), and the Coulomb constant (ke), allowed defining a system of units for quantities such as length, mass, time, electric charge, and temperature which were truly fundamental: derived from the properties of the universe we inhabit, and therefore comprehensible to intelligent beings anywhere in the universe. Most systems of measurement are derived from parochial anthropocentric quantities such as the temperature of somebody's armpit or the supposed distance from the north pole to the equator. Planck's natural units have no such dependencies, and when one does physics using them, equations become simpler and more comprehensible. The magnitudes of the Planck units are so far removed from the human scale they're unlikely to find any application outside theoretical physics (imagine speed limit signs expressed in a fraction of the speed of light, or road signs giving distances in Planck lengths of 1.62×10−35 metres), but they reflect the properties of the universe and may indicate the limits of our ability to understand it (for example, it may not be physically meaningful to speak of a distance smaller than the Planck length or an interval shorter than the Planck time [5.39×10−44 seconds]).

Planck's life was long and productive, and he enjoyed robust health (he continued his long hikes in the mountains into his eighties), but was marred by tragedy. His first wife, Marie, died of tuberculosis in 1909. He outlived four of his five children. His son Karl was killed in 1916 in World War I. His two daughters, Grete and Emma, both died in childbirth, in 1917 and 1919. His son and close companion Erwin, who survived capture and imprisonment by the French during World War I, was arrested and executed by the Nazis in 1945 for suspicion of involvement in the Stauffenberg plot to assassinate Hitler. (There is no evidence Erwin was a part of the conspiracy, but he was anti-Nazi and knew some of those involved in the plot.) Planck was repulsed by the Nazis, especially after a private meeting with Hitler in 1933, but continued in his post as the head of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society until 1937. He considered himself a German patriot and never considered emigrating (and doubtless his being 75 years old when Hitler came to power was a consideration). He opposed and resisted the purging of Jews from German scientific institutions and the campaign against “Jewish science”, but when ordered to dismiss non-Aryan members of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, he complied. When Heisenberg approached him for guidance, he said, “You have come to get my advice on political questions, but I am afraid I can no longer advise you. I see no hope of stopping the catastrophe that is about to engulf all our universities, indeed our whole country. … You simply cannot stop a landslide once it has started.” Planck's house near Berlin was destroyed in an Allied bombing raid in February 1944, and with it a lifetime of his papers, photographs, and correspondence. (He and his second wife Marga had evacuated to Rogätz in 1943 to escape the raids.) As a result, historians have only limited primary sources from which to work, and the present book does an excellent job of recounting the life and science of a man whose work laid part of the foundations of twentieth century science.