- Keating, Brian. Losing the Nobel Prize. New York: W. W. Norton, 2018. ISBN 978-1-324-00091-4.

-

Ever since the time of Galileo, the history of astronomy has

been punctuated by a series of “great

debates”—disputes between competing theories of the

organisation of the universe which observation and experiment

using available technology are not yet able to resolve one way

or another. In Galileo's time, the great debate was between the

Ptolemaic model, which placed the Earth at the centre of the

solar system (and universe) and the competing Copernican model

which had the planets all revolving around the Sun. Both models

worked about as well in predicting astronomical phenomena such

as eclipses and the motion of planets, and no observation made

so far had been able to distinguish them.

Then, in 1610, Galileo turned his primitive telescope to

the sky and observed the bright planets Venus and Jupiter.

He found Venus to exhibit phases, just like the Moon, which

changed over time. This would not happen in the Ptolemaic

system, but is precisely what would be expected in the

Copernican model—where Venus circled the Sun in an orbit

inside that of Earth. Turning to Jupiter, he found it to

be surrounded by four bright satellites (now called the

Galilean moons) which orbited the giant planet. This further

falsified Ptolemy's model, in which the Earth was the sole

source of attraction around which all celestial bodies

revolved. Since anybody could build their own telescope

and confirm these observations, this effectively resolved

the first great debate in favour of the Copernican heliocentric

model, although some hold-outs in positions of authority

resisted its dethroning of the Earth as the centre of

the universe.

This dethroning came to be called the “Copernican

principle”, that Earth occupies no special place in the

universe: it is one of a number of planets orbiting an ordinary

star in a universe filled with a multitude of other stars.

Indeed, when Galileo observed the star cluster we call the

Pleiades,

he saw myriad stars too dim to be visible to the

unaided eye. Further, the bright stars were surrounded by

a diffuse bluish glow. Applying the Copernican principle

again, he argued that the glow was due to innumerably more

stars too remote and dim for his telescope to resolve, and

then generalised that the glow of the Milky Way was also

composed of uncountably many stars. Not only had the Earth been

demoted from the centre of the solar system, so had the Sun

been dethroned to being just one of a host of stars possibly

stretching to infinity.

But Galileo's inference from observing the Pleiades was

wrong. The glow that surrounds the bright stars is

due to interstellar dust and gas which reflect light

from the stars toward Earth. No matter how large or powerful

the telescope you point toward such a

reflection

nebula, all you'll ever see is a smooth glow. Driven by

the desire to confirm his Copernican convictions, Galileo had

been fooled by dust. He would not be the last.

William

Herschel was an eminent musician and composer, but his

passion was astronomy. He pioneered the large reflecting

telescope, building more than sixty telescopes. In 1789, funded

by a grant from King George III, Herschel completed a reflector

with a mirror 1.26 metres in diameter, which remained the largest

aperture telescope in existence for the next fifty years. In

Herschel's day, the great debate was about the Sun's position

among the surrounding stars. At the time, there was no way to

determine the distance or absolute brightness of stars, but

Herschel decided that he could compile a map of the galaxy (then

considered to be the entire universe) by surveying the number of

stars in different directions. Only if the Sun was at the

centre of the galaxy would the counts be equal in all

directions.

Aided by his sister Caroline, a talented astronomer herself, he

eventually compiled a map which indicated the galaxy was in

the shape of a disc, with the Sun at the centre. This seemed to

refute the Copernican view that there was nothing special about

the Sun's position. Such was Herschel's reputation that this

finding, however puzzling, remained unchallenged until 1847

when Wilhelm Struve discovered that Herschel's results had been

rendered invalid by his failing to take into account the absorption

and scattering of starlight by interstellar dust. Just as you

can only see the same distance in all directions while within

a patch of fog, regardless of the shape of the patch, Herschel's

survey could only see so far before extinction of light by dust

cut off his view of stars. Later it was discovered that the

Sun is far from the centre of the galaxy. Herschel had been fooled

by dust.

In the 1920s, another great debate consumed astronomy. Was the

Milky Way the entire universe, or were the “spiral

nebulæ” other “island universes”,

galaxies in their own right, peers of the Milky Way? With no

way to measure distance or telescopes able to resolve them into

stars, many astronomers believed spiral neublæ were nearby

objects, perhaps other solar systems in the process of

formation. The discovery of a

Cepheid

variable star in the nearby Andromeda “nebula”

by Edwin Hubble in 1923 allowed settling this debate. Andromeda

was much farther away than the most distant stars found in the

Milky Way. It must, then be a separate galaxy. Once again,

demotion: the Milky Way was not the entire universe, but just

one galaxy among a multitude.

But how far away were the galaxies? Hubble continued his search

and measurements and found that the more distant the galaxy,

the more rapidly it was receding from us. This meant the

universe was expanding. Hubble was then able to

calculate the age of the universe—the time when all of the

galaxies must have been squeezed together into a single point.

From his observations, he computed this age at two billion

years. This was a major embarrassment: astrophysicists and

geologists were confident in dating the Sun and Earth at around

five billion years. It didn't make any sense for them to be

more than twice as old as the universe of which they were a

part. Some years later, it was discovered that Hubble's

distance estimates were far understated because he failed to

account for extinction of light from the stars he measured due

to dust. The universe is now known to be seven times the age

Hubble estimated. Hubble had been fooled by dust.

By the 1950s, the expanding universe was generally accepted and

the great debate was whether it had come into being in some

cataclysmic event in the past (the “Big Bang”) or

was eternal, with new matter spontaneously appearing to form new

galaxies and stars as the existing ones receded from one another

(the “Steady State” theory). Once again, there were

no observational data to falsify either theory. The Steady State

theory was attractive to many astronomers because it was the

more “Copernican”—the universe would appear

overall the same at any time in an infinite past and future, so

our position in time is not privileged in any way, while in the

Big Bang the distant past and future are very different than the

conditions we observe today. (The rate of matter creation required

by the Steady State theory was so low that no plausible laboratory

experiment could detect it.)

The discovery of the

cosmic

background radiation in 1965 definitively settled the debate

in favour of the Big Bang. It was precisely what was expected if

the early universe were much denser and hotter than conditions today,

as predicted by the Big Bang. The Steady State theory made no

such prediction and was, despite rear-guard actions by some

of its defenders (invoking dust to explain the detected radiation!),

was considered falsified by most researchers.

But the Big Bang was not without its own problems. In

particular, in order to end up with anything like the universe

we observe today, the initial conditions at the time of the Big

Bang seemed to have been fantastically fine-tuned (for example,

an infinitesimal change in the balance between the density and

rate of expansion in the early universe would have caused the

universe to quickly collapse into a black hole or disperse into

the void without forming stars and galaxies). There was no

physical reason to explain these fine-tuned values; you had to

assume that's just the way things happened to be, or that a

Creator had set the dial with a precision of dozens of decimal

places.

In 1979, the theory of

inflation

was proposed. Inflation held that in an instant after the Big

Bang the size of the universe blew up exponentially so that all

the observable universe today was, before inflation, the size of

an elementary particle today. Thus, it's no surprise that the

universe we now observe appears so uniform. Inflation so neatly

resolved the tensions between the Big Bang theory and

observation that it (and refinements over the years) became

widely accepted. But could inflation be observed?

That is the ultimate test of a scientific theory.

There have been numerous cases in science where many years elapsed

between a theory being proposed and definitive experimental

evidence for it being found. After Galileo's observations,

the Copernican theory that the Earth orbits the Sun became

widely accepted, but there was no direct evidence for

the Earth's motion with respect to the distant stars until the

discovery of the

aberration

of light in 1727. Einstein's theory of general relativity

predicted gravitational radiation in 1915, but the phenomenon was

not directly detected by experiment until a century later.

Would inflation have to wait as long or longer?

Things didn't look promising. Almost everything we know about the universe comes from observations of electromagnetic radiation: light, radio waves, X-rays, etc., with a little bit more from particles (cosmic rays and neutrinos). But the cosmic background radiation forms an impenetrable curtain behind which we cannot observe anything via the electromagnetic spectrum, and it dates from around 380,000 years after the Big Bang. The era of inflation was believed to have ended 10−32 seconds after the Bang; considerably earlier. The only “messenger” which could possibly have reached us from that era is gravitational radiation. We've just recently become able to detect gravitational radiation from the most violent events in the universe, but no conceivable experiment would be able to detect this signal from the baby universe.

So is it hopeless? Well, not necessarily…. The cosmic background radiation is a snapshot of the universe as it existed 380,000 years after the Big Bang, and only a few years after it was first detected, it was realised that gravitational waves from the very early universe might have left subtle imprints upon the radiation we observe today. In particular, gravitational radiation creates a form of polarisation called B-modes which most other sources cannot create. If it were possible to detect B-mode polarisation in the cosmic background radiation, it would be a direct detection of inflation. While the experiment would be demanding and eventually result in literally going to the end of the Earth, it would be strong evidence for the process which shaped the universe we inhabit and, in all likelihood, a ticket to Stockholm for those who made the discovery. This was the quest on which the author embarked in the year 2000, resulting in the deployment of an instrument called BICEP1 (Background Imaging of Cosmic Extragalactic Polarization) in the Dark Sector Laboratory at the South Pole. Here is my picture of that laboratory in January 2013. The BICEP telescope is located in the foreground inside a conical shield which protects it against thermal radiation from the surrounding ice. In the background is the South Pole Telescope, a millimetre wave antenna which was not involved in this research.

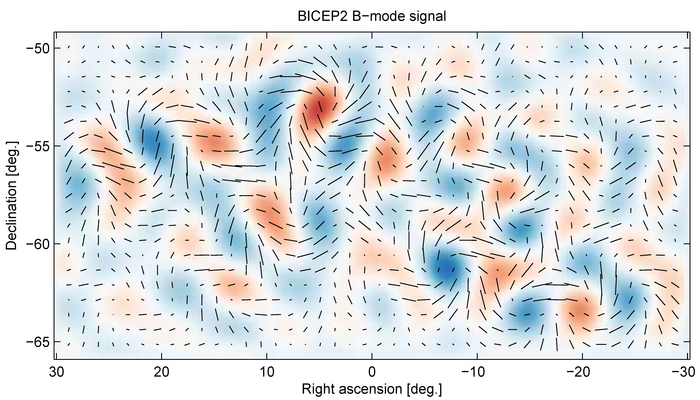

BICEP1 was a prototype, intended to test the technologies to be used in the experiment. These included cooling the entire telescope (which was a modest aperture [26 cm] refractor, not unlike Galileo's, but operating at millimetre wavelengths instead of visible light) to the temperature of interstellar space, with its detector cooled to just ¼ degree above absolute zero. In 2010 its successor, BICEP2, began observation at the South Pole, and continued its run into 2012. When I took the photo above, BICEP2 had recently concluded its observations. On March 17th, 2014, the BICEP2 collaboration announced, at a press conference, the detection of B-mode polarisation in the region of the southern sky they had monitored. Note the swirling pattern of polarisation which is the signature of B-modes, as opposed to the starburst pattern of other kinds of polarisation.

But, not so fast, other researchers cautioned. The risk in doing “science by press release” is that the research is not subjected to peer review—criticism by other researchers in the field—before publication and further criticism in subsequent publications. The BICEP2 results went immediately to the front pages of major newspapers. Here was direct evidence of the birth cry of the universe and confirmation of a theory which some argued implied the existence of a multiverse—the latest Copernican demotion—the idea that our universe was just one of an ensemble, possibly infinite, of parallel universes in which every possibility was instantiated somewhere. Amid the frenzy, a few specialists in the field, including researchers on competing projects, raised the question, “What about the dust?” Dust again! As it happens, while gravitational radiation can induce B-mode polarisation, it isn't the only thing which can do so. Our galaxy is filled with dust and magnetic fields which can cause those dust particles to align with them. Aligned dust particles cause polarised reflections which can mimic the B-mode signature of the gravitational radiation sought by BICEP2. The BICEP2 team was well aware of this potential contamination problem. Unfortunately, their telescope was sensitive only to one wavelength, chosen to be the most sensitive to B-modes due to primordial gravitational radiation. It could not, however, distinguish a signal from that cause from one due to foreground dust. At the same time, however, the European Space Agency Planck spacecraft was collecting precision data on the cosmic background radiation in a variety of wavelengths, including one sensitive primarily to dust. Those data would have allowed the BICEP2 investigators to quantify the degree their signal was due to dust. But there was a problem: BICEP2 and Planck were direct competitors. Planck had the data, but had not released them to other researchers. However, the BICEP2 team discovered that a member of the Planck collaboration had shown a slide at a conference of unpublished Planck observations of dust. A member of the BICEP2 team digitised an image of the slide, created a model from it, and concluded that dust contamination of the BICEP2 data would not be significant. This was a highly dubious, if not explicitly unethical move. It confirmed measurements from earlier experiments and provided confidence in the results. In September 2014, a preprint from the Planck collaboration (eventually published in 2016) showed that B-modes from foreground dust could account for all of the signal detected by BICEP2. In January 2015, the European Space Agency published an analysis of the Planck and BICEP2 observations which showed the entire BICEP2 detection was consistent with dust in the Milky Way. The epochal detection of inflation had been deflated. The BICEP2 researchers had been deceived by dust. The author, a founder of the original BICEP project, was so close to a Nobel prize he was already trying to read the minds of the Nobel committee to divine who among the many members of the collaboration they would reward with the gold medal. Then it all went away, seemingly overnight, turned to dust. Some said that the entire episode had injured the public's perception of science, but to me it seems an excellent example of science working precisely as intended. A result is placed before the public; others, with access to the same raw data are given an opportunity to critique them, setting forth their own raw data; and eventually researchers in the field decide whether the original results are correct. Yes, it would probably be better if all of this happened in musty library stacks of journals almost nobody reads before bursting out of the chest of mass media, but in an age where scientific research is funded by agencies spending money taken from hairdressers and cab drivers by coercive governments under implicit threat of violence, it is inevitable they will force researchers into the public arena to trumpet their “achievements”. In parallel with the saga of BICEP2, the author discusses the Nobel Prizes and what he considers to be their dysfunction in today's scientific research environment. I was surprised to learn that many of the curious restrictions on awards of the Nobel Prize were not, as I had heard and many believe, conditions of Alfred Nobel's will. In fact, the conditions that the prize be shared no more than three ways, not be awarded posthumously, and not awarded to a group (with the exception of the Peace prize) appear nowhere in Nobel's will, but were imposed later by the Nobel Foundation. Further, Nobel's will explicitly states that the prizes shall be awarded to “those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit to mankind”. This constraint (emphasis mine) has been ignored since the inception of the prizes. He decries the lack of “diversity” in Nobel laureates (by which he means, almost entirely, how few women have won prizes). While there have certainly been women who deserved prizes and didn't win (Lise Meitner, Jocelyn Bell Burnell, and Vera Rubin are prime examples), there are many more men who didn't make the three laureates cut-off (Freeman Dyson an obvious example for the 1965 Physics Nobel for quantum electrodynamics). The whole Nobel prize concept is capricious, and rewards only those who happen to be in the right place at the right time in the right field that the committee has decided deserves an award this year and are lucky enough not to die before the prize is awarded. To imagine it to be “fair” or representative of scientific merit is, in the estimation of this scribbler, in flying unicorn territory. In all, this is a candid view of how science is done at the top of the field today, with all of the budget squabbles, maneuvering for recognition, rivalry among competing groups of researchers, balancing the desire to get things right with the compulsion to get there first, and the eye on that prize, given only to a few in a generation, which can change one's life forever. Personally, I can't imagine being so fixated on winning a prize one has so little chance of gaining. It's like being obsessed with winning the lottery—and about as likely. In parallel with all of this is an autobiographical account of the career of a scientist with its ups and downs, which is both a cautionary tale and an inspiration to those who choose to pursue that difficult and intensely meritocratic career path. I recommend this book on all three tracks: a story of scientific discovery, mis-interpretation, and self-correction, the dysfunction of the Nobel Prizes and how they might be remedied, and the candid story of a working scientist in today's deeply corrupt coercively-funded research environment.