This thin volume (just 232 pages in the hardcover edition, only

around 125 of which are the main text and appendices—the

rest being extensive source citations, notes, and indices of

subjects and people and place names) is intended as the

introduction to an envisioned three volume work on Sparta

covering its history from the archaic period through the

second

battle of Mantinea in 362 b.c.

where defeat of a Sparta-led alliance at the hands of the

Thebans paved the way for the Macedonian conquest of Sparta.

In this work, the author adopts the approach to political

science used in antiquity by writers such as Thucydides,

Xenophon, and Aristotle: that the principal factor in

determining the character of a political community is

its constitution, or form of government, the rules

which define membership in the community and which

its members were expected to obey, their

character being largely determined by the system of

education and moral formation which shape the citizens

of the community.

Discerning these characteristics in any ancient society is

difficult, but especially so in the case of Sparta, which

was a society of warriors, not philosophers and historians.

Almost all of the contemporary information we have about

Sparta comes from outsiders who either visited the city at

various times in its history or based their work upon the

accounts of others who had. Further, the Spartans were

famously secretive about the details of their society, so

when ancient accounts differ, it is difficult to determine

which, if any, is correct. One gets the sense that all of

the direct documentary information we have about Sparta would

fit on one floppy disc: everything else is interpretations

based upon that meagre foundation. In recent centuries,

scholars studying Sparta have seen it as everything from

the prototype of constitutional liberty to a precursor of

modern day militaristic totalitarianism.

Another challenge facing the modern reader and, one suspects,

many ancients, in understanding Sparta was how profoundly

weird it was. On several occasions whilst reading

the book, I was struck that rarely in science fiction does one

encounter a description of a society so thoroughly

alien to those with which we are accustomed from our own

experience or a study of history. First of all,

Sparta was tiny: there were never as many as ten

thousand full-fledged citizens. These citizens

were descended from Dorians who had invaded the

Peloponnese in the archaic period and subjugated the original

inhabitants, who became

helots: essentially

serfs who worked the estates of the Spartan aristocracy in

return for half of the crops they produced (about the same

fraction of the fruit of their labour the helots of our modern

enlightened self-governing societies are allowed to retain

for their own use). Every full citizen, or Spartiate,

was a warrior, trained from boyhood to that end. Spartiates

not only did not engage in trade or work as craftsmen: they were

forbidden to do so—such work was performed by non-citizens.

With the helots outnumbering Spartiates by a factor of from

four to seven (and even more as the Spartan population shrunk

toward the end), the fear of an uprising was ever-present, and

required maintenance of martial prowess among the Spartiates

and subjugation of the helots.

How were these warriors formed? Boys were taken from their

families at the age of seven and placed in a barracks with others

of their age. Henceforth, they would return to their families only

as visitors. They were subjected to a regime of physical and

mental training, including exercise, weapons training, athletics,

mock warfare, plus music and dancing. They learned the poetry,

legends, and history of the city. All learned to read and

write. After intense scrutiny and regular tests, the young

man would face a rite of passage,

krupteίa,

in which, for a full year, armed only with a dagger, he had to

survive on his own in the wild, stealing what he needed, and

instilling fear among the helots, who he was authorised to

kill if found in violation of curfew. Only after surviving this

ordeal would the young Spartan be admitted as a member of a

sussιtίon,

a combination of a men's club, a military mess, and the basic unit

in the Spartan army. A Spartan would remain a member of this

same group all his life and, even after marriage and fatherhood,

would live and dine with them every day until the age of

forty-five.

From the age of twelve, boys in training would usually have

a patron, or surrogate father, who was expected to initiate

him into the world of the warrior and instruct him in the

duties of citizenship. It was expected that there would be

a homosexual relationship between the two, and that this would

further cement the bond of loyalty to his brothers in arms. Upon

becoming a full citizen and warrior, the young man was

expected to take on a boy and continue the tradition. As

to many modern utopian social engineers, the family was seen

as an obstacle to the citizen's identification with the

community (or, in modern terminology, the state), and the

entire process of raising citizens seems to have been designed

to transfer this inherent biological solidarity with kin to

peers in the army and the community as a whole.

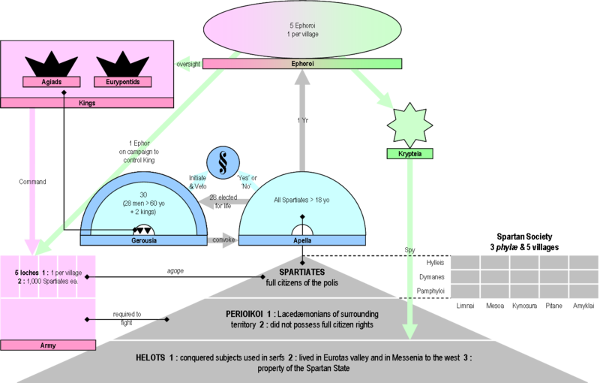

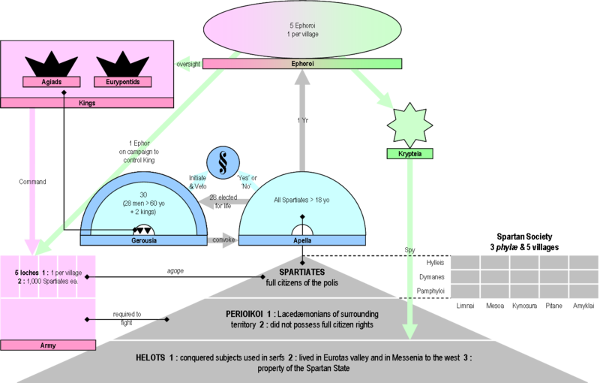

The political structure which sustained and, in turn, was

sustained by these cultural institutions was similarly

alien and intricate—so much so that I found myself

wishing that Professor Rahe had included a diagram to help

readers understand all of the moving parts and how

they interacted. After finishing the book, I found this one

on Wikipedia.

Image by Wikipedia user

Putinovac

licensed under the

Creative Commons

Attribution

3.0 Unported license.

The actual relationships are even more complicated and subtle

than expressed in this diagram, and given the extent to which

scholars dispute the details of the Spartan political institutions

(which occupy many pages in the end notes), it is likely

the author may find fault with some aspects of this illustration.

I present it purely because it provides a glimpse of the

complexity and helped me organise my thoughts about the

description in the text.

Start with the kings. That's right, “kings”—there

were two of them—both traditionally descended from

Hercules, but through different lineages. The kings shared power and

acted as a check on each other. They were commanders of the army

in time of war, and high priests in peace. The kingship was hereditary

and for life.

Five overseers, or ephors were elected annually by the citizens

as a whole. Scholars dispute whether ephors could serve more than

one term, but the author notes that no ephor is known to have done

so, and it is thus likely they were term limited to a single year.

During their year in office, the board of five ephors (one from each

of the villages of Sparta) exercised almost unlimited power in both

domestic and foreign affairs. Even the kings were not immune to their

power: the ephors could arrest a king and bring him to trial on a

capital charge just like any other citizen, and this happened. On

the other hand, at the end of their one year term, ephors were

subject to a judicial examination of their acts in office and

liable for misconduct. (Wouldn't be great if present-day “public

servants” received the same kind of scrutiny at the end of

their terms in office? It would be interesting to see what a

prosecutor could discover about how so many of these solons manage

to amass great personal fortunes incommensurate with their salaries.)

And then there was the “fickle meteor of doom” rule.

Every ninth year, the five [ephors] chose a clear and moonless

night and remained awake to watch the sky. If they saw a

shooting star, they judged that one or both kings had acted

against the law and suspended the man or men from office. Only

the intervention of Delphi or Olympia could effect a

restoration.

I can imagine the kings hoping they didn't

pick a night in mid-August

for their vigil!

The ephors could also summon the council of elders, or

gerousίa,

into session. This body was made up of thirty men: the two kings, plus

twenty-eight others, all sixty years or older, who were elected for

life by the citizens. They tended to be wealthy aristocrats from

the oldest families, and were seen as protectors of the stability

of the city from the passions of youth and the ambition of kings.

They proposed legislation to the general assembly of all citizens,

and could veto its actions. They also acted as a supreme court in

capital cases. The general assembly of all citizens, which could

also be summoned by the ephors, was restricted to an up or down

vote on legislation proposed by the elders, and, perhaps, on

sentences of death passed by the ephors and elders.

All of this may seem confusing, if not downright baroque,

especially for a community which, in the modern world, would be

considered a medium-sized town. Once again, it's something which,

if you encountered it in a science fiction novel, you might expect

the result of a

Golden

Age author, paid by the word, making ends meet by

inventing fairy castles of politics. But this is how Sparta seems

to have worked (again, within the limits of that single floppy disc

we have to work with, and with almost every detail a matter of dispute

among those who have spent their careers studying Sparta over the

millennia). Unlike the U.S. Constitution, which was the product of

a group of people toiling over a hot summer in Philadelphia, the

Spartan constitution, like that of Britain, evolved

organically over centuries, incorporating tradition, the consequences

of events, experience, and cultural evolution. And, like the

British constitution, it was unwritten. But it incorporated, among all

its complexity and ambiguity, something very important, which can be

seen as a milestone in humankind's millennia-long struggle against

arbitrary authority and quest for individual liberty: the separation

of powers. Unlike almost all other political systems in antiquity

and all too many today, there was no pyramid with a king, priest,

dictator, judge, or even popular assembly at the top. Instead,

there was a complicated network of responsibility, in which any

individual player or institution could be called to account by

others. The regimentation, destruction of the family, obligatory

homosexuality, indoctrination of the youth into identification with

the collective, foundation of the society's economics on serfdom,

suppression of individual initiative and innovation were, indeed,

almost a model for the most dystopian of modern tyrannies, yet darned

if they didn't get the separation of powers right! We owe much of

what remains of our liberties to that heritage.

Although this is a short book and this is a lengthy review, there is

much more here to merit your attention and consideration. It's a

chore getting through the end notes, as much of them are source

citations in the dense jargon of classical scholars, but embedded

therein are interesting discussions and asides which expand upon

the text.

In the Kindle edition, all of the citations and

index references are properly linked to the text. Some Greek

letters with double diacritical marks are rendered as images

and look odd embedded in text; I don't know if they appear correctly

in print editions.

August 2017