|

|

While “The New Technological Corporation” focused on largely on the theory underlying the special strategies appropriate to a company like Autodesk, this memo, circulated to senior management in the fall of 1990, concentrated on details. It seemed obvious to me that the boom of the 1980's could not go on forever, and that there were specific danger signs on the horizon. It's much easier to see trouble on the horizon than to know precisely when it will arrive, but fortunately a company in Autodesk's position need not forgo opportunities in order to protect against turbulence.

To: Central Committee

From: John Walker

Date: September 7th, 1989

Subject: Autodesk at Max Q

Max Q. In aerodynamics, particularly rocketry, maximum dynamic pressure; the moment when velocity, trajectory, altitude, and ambient atmospheric temperature and pressure combine to exert the maximum stress upon the vehicle. Most catastrophic failures occur at this moment.

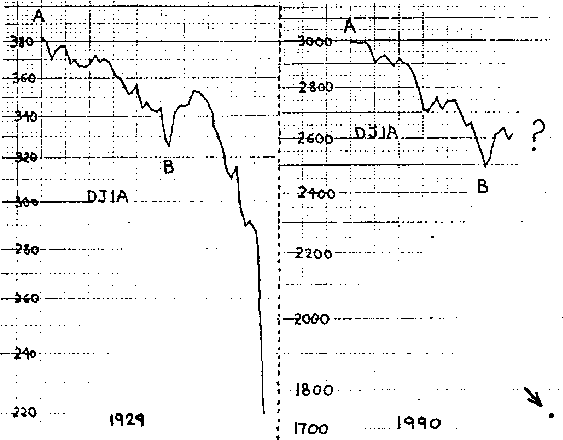

Viewing the history of Autodesk's growth, as outsiders do, by

examining a chart of sales, earnings, units installed, market share,

stock price, or any other aggregate metric of performance gives the

impression that Autodesk has achieved its success with relatively little

difficulty. Indeed, other than blips in the stock price triggered by

exogenous events such as the Crash of 1987,![]() almost every measure of

Autodesk's performance is a monotonically increasing curve, devoid

of both gut-wrenching plunges and giddy, unsustainable spurts of

growth. It's the kind of performance that tempts one into believing

that change of this magnitude can be managed—that one can guarantee

this kind of performance in the future—forgetting that we're simply

trying to ride a wave of technological change without drowning,

slipping off into stagnant backwaters, or being dashed on the

rocks by excessive assumption of risk.

almost every measure of

Autodesk's performance is a monotonically increasing curve, devoid

of both gut-wrenching plunges and giddy, unsustainable spurts of

growth. It's the kind of performance that tempts one into believing

that change of this magnitude can be managed—that one can guarantee

this kind of performance in the future—forgetting that we're simply

trying to ride a wave of technological change without drowning,

slipping off into stagnant backwaters, or being dashed on the

rocks by excessive assumption of risk.

Having lived through the hundreds of thousands of individual events which collectively add up to the numbers on the chart, we know very well that nothing about Autodesk's success came easily. Building the company required ignoring conventional wisdom, willingness to improvise in the face of inadequate resources, and to do whatever was necessary to make our products meet our customers' needs, even if it meant undertaking technical tasks rarely attempted by “application vendors” or scratch-building entire channels of distribution, training, and support where none existed before.

And yet, in one sense Autodesk has had it relatively easy since 1982. When people ask me about the “key strategic decisions” made while I was involved in managing the company, my response is that most of the crucial decisions: the ones which, in retrospect, were central in achieving the market position we have today, were not at all difficult to make. In fact, most of those decisions were arrived at simply because they were essentially the only courses of action open to us at the time. Other paths leading to alternative destinies for Autodesk were foreclosed due to lack of resources, prerequisites, or imagination. I refer to this as “management by lack of alternatives” and, although not conducive to one's being perceived as a super-manager, it has served Autodesk well.

One of the reasons so many decisions seemed obvious, and that Autodesk prospered from pursuing opportunities in a straightforward manner is that throughout our company's history the fundamental economic and technological trends that were in effect when Autodesk was founded have remained intact. The 1980s were a time of enormous, indeed mindboggling, change. Autodesk was organised at the absolute bottom of the 1982 recession—one of the most severe economic slumps since the Great Depression. As Autodesk's incorporation papers were being prepared and filed, the Dow Jones Industrial Average dipped below 800, marking a low point never reached since. Unemployment was over 10%, interest rates were declining from their 1981 peaks that shattered all records since the Civil War, and gloom was everywhere. Polish workers, near open rebellion against communist rule, were suppressed by a military junta installed to preempt Soviet intervention. For the first time since the 1950s, sober observers in both the East and West began to think of nuclear war as a real possibility. And IBM, to the bafflement of most onlookers, chose a virtually unknown architecture, the Intel 8088, an obscure operating system, MS-DOS, and brought to market a personal computer for which there was no application software.

Our perception that the advent of the mass-marketed personal and office computer, whatever the source, would create an enormous demand for application software led us to create Autodesk in 1982. In a way, even the founding of the company reflected a lack of alternatives. My prior company, Marinchip, was expiring from technological obsolescence and lack of aggressive management, and I had to figure out what to do next. Experience had taught me that software was a much better business than hardware, so that's what I decided to do….

In 1982, it was far from clear which way things were going to go. Had the economy continued to deteriorate, had the world drifted toward further polarisation and confrontation, or had the microcomputing market become increasingly fragmented and unable to evolve industry standards able to sustain a viable application market, we would not be here today plotting how best to steer Autodesk through the uncertain times ahead. Indeed, we might not be here at all.

But, in 1982, the downtrends in so many things economic, political, and technological began to turn up ever so subtly. Slowly things began to improve. Confidence returned, technology resumed its exponential growth, and Autodesk never lost the position we had staked out for ourselves in 1982—the world leader in computer aided design. Time passes. Things change. People adapt. Suppose I had included the following paragraphs as the inspirational closer of the original Working Paper for the organisation of Autodesk?

Who knows what the future may hold? Perhaps, as the 1980s pass into the last decade of this century, we'll see a world very different from the dark world of today and, if we draw our plans carefully and strive to make them real, the fruit of our labours may have grown into an enterprise that leads its industry into that new decade.

Small changes add up. Reality eventually will out. Today, we're trying to scrape together enough money to give our partnership a six month lease on life: enough for one good shot at success. If we fail, we go back to our jobs and chalk it off to experience. If we succeed…. If we succeed….

The year is 1990. After much strife and suffering, chaos and confusion, we finally ended up naming the company “Autodesk”. Every founder has made a million dollars or more from his original investment; those with the greatest confidence in the company have reaped the greatest rewards. Every two cents invested in Autodesk stock has grown to more than sixty dollars. One of Autodesk's products has become the overwhelming global leader in its market—indeed, it created the market, and has spawned an entire industry of related products.

Today, we're worrying about filling our treasury. In 1990, I see our company sitting on a hoard of cash exceeding $140 million and viewing that very evidence of success as a problem: “what to do with all the money.” It's a nice problem to have.

Our company's success is world-wide, and what a different world it will be in 1990. The Berlin Wall will have been smashed to rubble by sledgehammers and Eastern Europe will have emerged from the aftermath of World War II to become what it was before—simply part of Europe. The Soviet Union will have a democratically elected parliament, debating the means and pace of transition from central planning to a market economy. More than half of the Soviet republics will be in various stages of secession from the Union. Our company, today dreaming of rolling out our first products in a trade show in the United States, will have organised successful trade shows in Moscow and Prague. And, as the tide of liberation sweeps the world, we'll remain in the vanguard by planning a show in Capetown for 1991.

![[Footnote]](i/footnote.png)

A very different world…. The Dow Jones Industrials have flirted with 3000 before pulling back; the U.S. national debt moves from trillion to trillion almost unnoticed, and Japan becomes the manufacturing power in the world. And in computing? Well, no end is in sight. Today, we're constrained by a 64K memory limit. In 1990, people will talk disdainfully of machines still limited by a “640K barrier”. The typical machine used to run our products will run between one hundred and one thousand times faster than the machines we're using today, and an entire market will have been created for hardware products developed specifically to accelerate the performance of our software. And looking forward from 1990, none of these trends appear limited by any fundamental constraints. Technological visionaries foresee computing at the molecular level—with the very stuff of life—and a time where individual computers and databases will coalesce into a common information pool providing access to the collected wisdom of humanity. And our company will be at the forefront of realising both of these goals.

Would you have joined a company organised by such an obviously raving lunatic?

Autodesk's trajectory in the first nine years has been steep, yet smooth. Autodesk's entire history to date has coincided with the longest period of uninterrupted economic expansion in this century. In the personal computing market, the IBM PC defined an open, extensible standard that was adopted worldwide as the desktop computing environment of choice. Cumulative change in computing has been revolutionary, but incremental in occurrence; Autodesk has not had to weather the transition from one standard to another as happened when machines of the IBM PC generation supplanted the CP/M Z-80 machines that went before.

Today, however, the future looks unsettled in every direction. There is every reason to believe that the calm and comprehensible environment in which we've built Autodesk may become turbulent and chaotic for a while. Autodesk enters this turbulence at high velocity, continuing to accelerate. It will be a period of maximum dynamic pressure on our company—Max Q. Autodesk's financial strength, market position, technological leadership, control of the channels of distribution, support for a wide variety of hardware and software platforms, and global diversification equip us to ride out this period of turbulence and emerge intact: strengthened, perhaps, with regard to competitors ill-prepared or unable to anticipate events that affect their plans.

But regardless of Autodesk's fundamental strengths, if even a minority of the events I suggest below come to pass, managing Autodesk in the next several years will be much more difficult than in the past. Hard choices will be required, and decisions with enormous consequences will have to be made with little assurance that they are correct.

In this paper, I'll try to survey some of the forms of turbulence that Autodesk may encounter in this period of Max Q, suggest alternatives for dealing with possible events that may transpire, and examine how Autodesk can emerge stronger and better positioned for the next period of growth which will follow, as surely as the changing of the seasons.

Having been called “Chicken Little” in the San Francisco Chronicle, I will remain consistent with the reputation given me by that august publication and enumerate some of the challenges we may be forced to deal with in the next two years.

In order to make my recommendations for dealing with these complicated and interrelated contingencies more clear, I'll first run through all the problems, then discuss what we might do about them in a separate section. Please don't get too depressed by this view of the future; Autodesk is in superb shape to ride out the turbulence I see ahead.

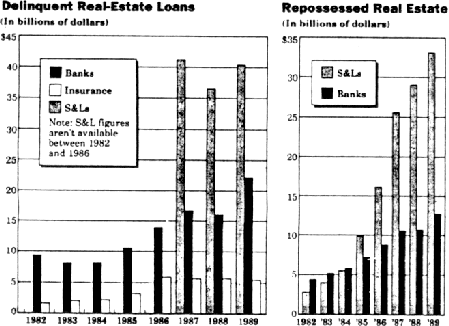

Even before the invasion of Kuwait and its aftermath in the financial markets, the economies of most industrialised countries were teetering on the verge of recession. After a prolonged economic expansion fueled by unprecedented growth of debt, strains were becoming apparent and were reflected in anemic GNP growth and dismal performance by the majority of stocks (excepting a few, highly capitalised, blue chips).

With $40 oil, interest rates kept high to prevent a further slide in the dollar, the drain of a half trillion dollar bail-out of what is laughably called the “thrift industry,” an incipient credit crunch induced by banks cutting back lending as their real-estate loans go sour, worrisome inflation numbers beginning to appear, a nasty bear market under way in both Wall Street and Tokyo, and new taxes thrown on top of the whole mess, the near term outlook is absolutely awful.

The consensus has been that there would probably be a recession, but that it would be a mild one. Unless I'm missing some fundamental fact or misinterpreting the data, what's coming looks awfully like a replay of 1974–1975 to me. And in that bone-crusher most companies weren't buried in debt as they are today.

This evaluation is based entirely on economic fundamentals. If a large scale, costly, and protracted war should erupt, the severity of the recession will be magnified enormously.

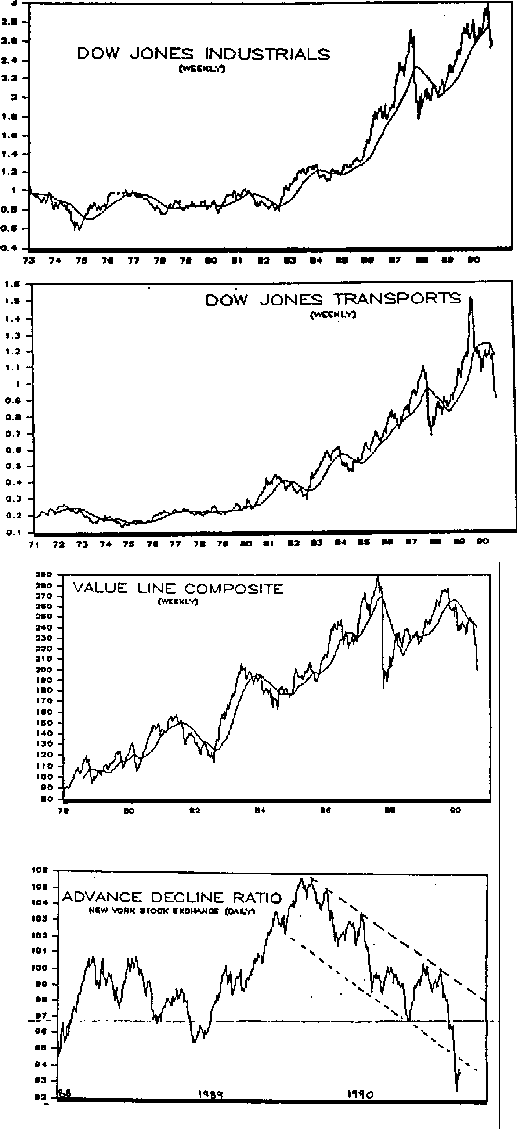

I believe the overall trend of the stock market turned down well before the Gulf crisis erupted. Fundamentally, stock prices reflect the prospects for corporate earnings, and given the economic circumstances I listed above, it's hard to be optimistic about the near term outlook for most companies. Once a bear market truly takes hold, it begins to feed on itself: headlines about plunging markets impair confidence, spending falls, sales reflect this, profits erode or turn into losses, dividends are cut, capital spending plans are scaled back, etc., etc., until the whole process ends in a downside spasm of despair and exhaustion, forming the base for the next advance.

Bear markets typically play out in three phases. In the first phase, stocks drift lower for no apparent reason. Most investors believe the sell-off is a normal consolidation before a further advance. In the second phase, stocks are falling for obvious reasons—companies are reporting lower earnings or losses, and many are skipping or reducing their dividends. In the final phase, stocks fall because people are dumping them to raise cash. Nobody wants to own stocks any more. This period of panic liquidation and exhaustion sets the stage for the next bull market (which occurs in three complementary phases). Today we're moving from the first to the second phase of this bear market. There isn't anything like enough fear around for this to be the final days of a bear market. In the recommendations section I'll discuss specific targets we can use as benchmarks for making stock-related decisions in this market.

For years, doomsayers have been foretelling the end of the absurd spiral in real estate prices. The argument for a downturn in the residential market is compelling; when most first-time buyers are priced entirely out of the market, you don't just need a greater fool to sustain the market, you need an infusion of new, wealthier, greater fools to buy. And wealthy fools are, as usual, in short supply.

Finally, these forecasts seem to be coming true. Even the California market, one of the last holdouts, now seems to be succumbing to the collapse in prices that appeared first in Texas and New England. While Autodesk's fortunes are tied only tenuously to the real estate market (although clearly the AEC sector of our business will be hard hit by a downturn in construction), the consequences of a sustained drop in real estate will interact with other financial events and magnify the economic problems.

Most of the wealth in the United States is in the form of real estate. As housing prices have risen, this has contributed not only to a general perception of prosperity and confidence, it has contributed real liquidity as well through the ubiquitous home equity loans. If this comes to an end, not only are people going to have less money to spend and less inclination to spend it, an enormous number of loans are going to start to look very iffy. As reserves are built against these loans, less money will be available for other purposes and this will contribute to the business downturn.

I believe we may be in the relatively early stages of a liquidation of some of the excesses in the real estate market, particularly in California. Even if things get no worse here than they are today in Texas, we have a long way to go. I think that this situation bears careful consideration before contemplating any major real estate purchase commitments.

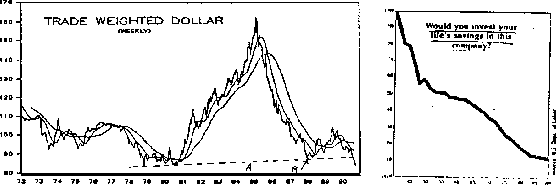

Yes, the dollar has crashed again. This has wiped out all the gains of the 1980s and reduces the real value of our liquid assets which are held overwhelmingly in dollars. More significantly, perhaps, it raises expectations of inflation and forecloses the option of revving up the economy by cutting interest rates.

Underlying most of the current troubles in the financial markets is the mountain of debt piled up in the 1980s. Government, corporations, and individuals have all leveraged themselves to the hilt, and as the economy slows, more and more borrowers may find themselves unable to service their debt.

So far, we've seen a rolling, industry by industry, liquidation of bad debt: oil drillers, Texas commercial real estate, junk bonds, savings and loans. Although each has contributed to the demise of the next and the overall tab continues to rise as each domino falls, so far the individual problems have been contained and prevented from leading to a general credit crunch that could cause widespread bankruptcies. Obviously it will be harder to avoid such an outcome if a deep recession occurs.

The debt to equity ratio of so many companies may give the coming recession a very different character from those of the past. In a company with minimal debt, a business slowdown leads to layoffs, reduced inventory, postponing or canceling capital investment plans, etc. Each of these contributes to the slowdown of other businesses and spreads throughout the economy. But a highly leveraged company is very likely to hit the wall by defaulting on its debt very early in a recession. If the debtor takes the obvious step of filing Chapter 11, the business continues to operate while a reorganisation plan is developed and implemented. Chapter 11 reorganisations give a high priority to the company's operating facilities and employment, while wiping out equity investment and either writing down debt or transforming it into equity in some manner.

Although this shrinks the money supply by wiping out equity and debt investments, the overall consequences may be better for the economy than protracted shrinking of a company, slowly squeezing its suppliers and the communities in which it operates. Or, it may be disastrously bad, leading to a chain-reaction of bankruptcies and illiquidity in the debt markets just when debt financing is essential to recovery. I don't know which way it will go; the point is that it's a new situation so behaviour in previous recessions can't provide much guidance as to what will happen this time. It bears thought and careful watching.

In times of tight credit, a cash rich, debt free company such as Autodesk is king. If we enter a period of accelerated debt liquidation (and imagine how insane it would have sounded five or six years ago to talk about a half-trillion dollar collapse of the entire savings and loan industry), Autodesk should pay even closer attention to the quality of the investments in which its cash is placed. It is far better in uncertain times to forgo a fraction of a percent of interest than to lose one's money at the very moment it's most valuable from a strategic standpoint.

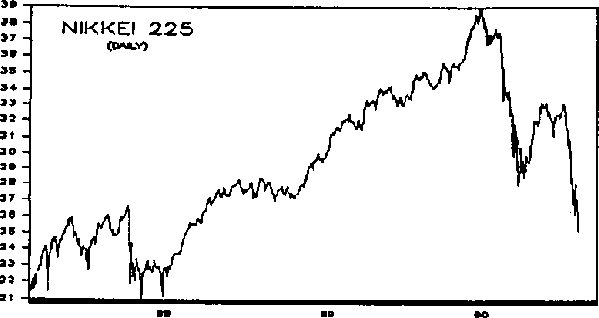

The stock market and real estate situation in the U.S. is mirrored in

Japan. However, prices in the Japanese stock and real estate markets

have risen to levels utterly disconnected from any conventional

measure of fundamental value. This suggests that once they begin to

fall, as is now happening, they may have a long, long way to go on the

downside.![]()

This is worrisome not only from the standpoint of the Japanese economy but also for its consequences for the U.S. Japan has been a major exporter of capital in the last decade—reinvesting its trade surpluses and providing liquidity by purchasing debt in the U.S. A collapse in the Japanese market could cause this source of capital to dry up as it is diverted to domestic Japanese needs, and this could accelerate the problems in the U.S.

I've been worried about the health of our domestic reseller channel for over three years. Many of the dealers who sell the bulk of our products today, in an expanding economy, are marginally profitable or losing money. As I pointed out last March in the memo “Are we bankrupting our dealers?” (copy attached), Autodesk's pricing policies may have contributed to this situation. If the economy contracts even a modest 10%, the probability is extremely high that many of our dealers would be forced out of business or into other sectors of the market.

If this happens, and Autodesk is not prepared to cope with it, it could be a catastrophe of the greatest magnitude for our company. Reseller distribution has been absolutely central to Autodesk's entire business concept since 1983. It is our dominance of the reseller channel that has made it so difficult for competitors to assail our market share. (The fact that we react so quickly to any attempt by competitors to recruit our dealers is evidence that we recognise this fact.) The very composition of our products and the structure of our company have been built around the dealer channel. Our promotional campaigns and sales literature reflect it. Devolving installation support, customisation, consulting on hardware configurations, selection and integration of application packages, informal training, and, most importantly, post-sale support, upon our dealers has been essential in maintaining Autodesk's very high profit margins over so many years. In a very real sense, we have offloaded many of the traditional cost centres of a CAD company onto our reseller organisations. The price we've paid for doing this is the risk we now run if those businesses begin to fail.

Unfortunately, the dealer viability crisis not a problem which

Autodesk has much leverage to solve, as far as I can see. If, as I

believe the market has demonstrated unambiguously, the value of

AutoCAD to a customer is between $2,000 and $2,500, then further

price increases will only further consume the resellers' margin in

forced discounts, reduce overall volume, and contribute to market

share erosion in favour of lower-priced alternative

products.![]()

Although Autodesk has contributed to its dealers' woes, the fundamental problem is not of our making. In the early days of AutoCAD, it took an experienced dealer simply to obtain the odd collection of hardware that was required to lash up a machine suitable for running AutoCAD, get it all to work together, and tweak the system so it delivered acceptable performance. Many of the peripherals required by CAD users, notably professional quality digitisers and large drafting plotters, had essentially no retail distribution channel at all. And, early AutoCAD was no great shakes when it came to ease of installation or the initial learning curve for a new user to become productive.

In such an environment the AutoCAD dealer added real value that was readily perceived by the customer. This is usually the case in emerging markets—it closely paralleled the development, a few years earlier, of businesses which configured and sold word processing systems based on CP/M machines and WordStar. The eventual demise of that business provides insight into what may be happening now in our reseller channel.

As the market has matured and the price-performance of computers and peripherals has skyrocketed, a CAD system is no longer a odd collection of exotic hardware that can be assembled only by a skilled technician. Instead, today one can order everything needed to assemble a high-end CAD system over the telephone, toll-free, and expect that when the boxes arrive it will take no more than a careful reading of the instructions to get everything working. Architectures such as the Macintosh and SPARCstation where component integration has been carefully thought out contribute to this trend.

In addition, a customer who previously turned to his local dealer as the only source of knowledge about AutoCAD can now read any one of dozens of books about the product, attend courses at a local school, call a 900 number support service, read an article in Cadalyst or Cadence, post a question on CompuServe, or turn to a fellow AutoCAD user for assistance either at a user group meeting or informally—our very success has engendered a proliferation of alternatives to the services originally provided only by dealers.

I wish these fundamentals were different or that I could find a fix for the problem. Our dealers have worked very hard for us for a very long time, and their efforts have been largely responsible for our success. But if the dealer channel is becoming nonviable, it is incumbent on Autodesk's management to anticipate that eventuality and have plans in place to cope with it should it occur.

Sooner or later we're going to have a down quarter.![]() If you'd asked me

the odds in 1985 that we'd make it more than five years from the IPO

without blowing a single quarter, I'd have said “no better than one

in twenty.” It is an absolute miracle that we've been able to

maintain our unbroken streak in the face of late product

introductions, hardware lock crises, stop-ship orders, and all the

other individual tribulations that disappear into the totals on the

financial statement.

If you'd asked me

the odds in 1985 that we'd make it more than five years from the IPO

without blowing a single quarter, I'd have said “no better than one

in twenty.” It is an absolute miracle that we've been able to

maintain our unbroken streak in the face of late product

introductions, hardware lock crises, stop-ship orders, and all the

other individual tribulations that disappear into the totals on the

financial statement.

However, we have operated so far in an expanding economy. If the

economy turns down, our dealer channel begins to encounter severe

problems, or we're forced to cut our price to maintain market share,

our unbroken streak will come to an end. This is inevitable, and

is virtually certain in a serious recession.![]()

While failing to meet expectations for a quarter might seem trivial

alongside the other dire circumstances in this gallery, it will have a

detrimental effect on morale at the very time when morale and sound

judgement are most important.![]() The currently-circulating jokes about

Oracle demonstrate how rapidly a company can go from darling to

dogshit. If Autodesk appears headed for a bad quarter, it is

important that the company, the analysts, and the shareholders be

prepared for the aftermath so that one piece of bad news doesn't end

up contributing to more.

The currently-circulating jokes about

Oracle demonstrate how rapidly a company can go from darling to

dogshit. If Autodesk appears headed for a bad quarter, it is

important that the company, the analysts, and the shareholders be

prepared for the aftermath so that one piece of bad news doesn't end

up contributing to more.

Ever since 1982, the general shape of the PC market has been relatively simple. The IBM PC defined a hardware standard; MS-DOS became the software standard, and applications battled for supremacy in the huge market that adhered to these standards. Although it was far from clear at the time, other architectures such as the Lisa, Unix workstations, Amigas, the Atari ST, and even the Macintosh were largely sideshows compared to the 90% of the market represented by the PC. The assumption that the PC would continue to develop along the obvious lines of faster processors, larger discs, more memory, better networks, and higher resolution graphics has been correct over Autodesk's entire history. Autodesk has profited enormously from this progress.

Recently, however, the future of the PC market has become very confusing to try to project. Since Autodesk, as an application vendor, is forced to choose which architectures will receive the attention of our limited technical, marketing, and promotional resources, uncertainty about the direction of the market complicates our job immensely. Worse, the same confusion that vexes us causes even more bafflement among our dealers and their customers. This lack of direction is bad for everybody—at the minimum it causes customers to defer purchase decisions until things sort themselves out. A customer forced to choose may end up with an incompatible system and waste his money and time on something that ends up being bypassed by the market.

What I'm basically talking about here is OS/2. I guess every decade or so IBM has to show the new kids in the industry who think they know how to screw things up what a débâcle of truly Wagnerian scope looks like. With the able assistance of Microsoft, uncertainty and confusion have been unleashed in the PC market to such an extent that people cannot even figure out which vendor is responsible for what product, no less when they might be able to buy a solution to the problems of existing PC users. Consider this: today there are more than forty million computers in place that share a common hardware and software architecture. Yet at this moment there is no clearly-defined path for the future migration of these machines which represent a collective investment of many billions of dollars.

What's a user to do? Struggle along with MS-DOS? Move to Windows and buy a whole new set of applications compatible with it? Choose products built with DOS extenders, then fight the mutual incompatibilities among them? Wait for OS/2…but which OS/2? Certainly not the awful one you can buy today, but the one coming from IBM or the one coming from Microsoft? But wait, Microsoft says they're developing a “portable” OS/2 that will run on non-Intel hardware. So are we going to end up scrapping our '386 machines for MIPS or Sparc chips? Crazy—but what's this news about Compaq narrowing their choice for a CPU vendor for their next generation to MIPS and Sun, Intel being notably absent? Chuck the whole thing and get a Macintosh? But a SPARCstation is less than $5,000 and a whole lot faster. And then there's the other side of IBM participating in OSF and promising true cross-platform application portability and yet another wonderful standard environment.

It's entirely possible that all of this disarray in the market may result in nothing more serious than an interlude in which the users continue to buy vanilla '386 and '486 DOS machines while they wait for the dust to settle and a clear direction to emerge. If that's the case then Autodesk need only be careful to avoid squandering too much of our development resources on each of the contending architectures until a winner becomes apparent. But if rampant confusion seems to be hurting the market for our products and further endangering our dealers, Autodesk must be prepared to provide guidance as to what we believe is the best path for our customers, even if it means abandoning some of our usual even-handedness with regard to hardware and operating system alternatives.

After this litany of dismaying facts, we can comfort ourselves with the knowledge that Autodesk could scarcely be in a stronger position to face whatever tomorrow may bring. Below I'll discuss specific recommendations for actions Autodesk should take to prepare for and react to the various contingencies I've discussed. What surprised me most in performing this analysis was how little any of these recommendations have to do with any particular view of the future. In no way do these recommendations constitute a “bet on bad times.” In fact, the most important thing of all is that regardless of what happens, Autodesk must remain focused on the most important aspects of its business: developing the best products, making them widely available at prices people can afford, innovating in distribution, support, and training, making the funds we commit to promotion go as far as possible, and preserving the financial strength that allows us to take a long term view of the market and our position within it.

Worse than any specific blunder would be for Autodesk, in the aftermath of a downturn in sales and profits brought about by a contracting economy as opposed to any errors on our part, to start flailing around with gimmicks and lose the confidence of our many constituencies. The higher the seas, the more important is the need for a steady hand on the tiller.

Many of the recommendations I discuss below have been raised before, and some may already be in various stages of implementation. I believe that even if an unexpected burst of prosperity startles everybody and the dark clouds fade away, Autodesk will be better able to cope with good times once these policies are in place.

Cash in the bank is always nice to have, but especially in a credit crunch. I agree that Autodesk presently has more cash than we need from the standpoint of survival, but I'd be disinclined to reduce the cash hoard at this time. If we muddle through the present economic problems, we can always bring down the cash once things are more settled. But if we do get a credit crunch and sharp recession, we'll be able to generate substantial earnings from our cash (and apply our high tech company P/E to it, as discussed on page 16 of “The New Technological Corporation”).

In addition, there's no better time to be a buyer than at the bottom. If we see a repeat of the 1974 recession, it's very likely we might be able to make some very attractive acquisitions and/or investments at bargain basement prices as the bear market reaches the point of panic liquidation. If this kind of situation begins to emerge, we should devote some effort to scanning the horizon for technologies that fit and which will prosper when recovery begins.

Consequently, I recommend that we do nothing to reduce our cash position at this time.

One of the bargain basement equity investments we can make with our cash is, of course, buying back shares of our own stock. By reducing the number of shares outstanding, we multiply the earnings per share from constant earnings, making each remaining share more valuable.

I have nothing against such a strategy, but I don't think now is the time to do it. Every measure I consider reliable tells me that we are in a primary bear market which began several months ago. Strength in the Dow has masked an ongoing massacre in the wider market. The Value Line Composite Index, for example, which comes far closer to reflecting an average stock portfolio, has utterly collapsed and is heading for its 1987 crash low. The advance-decline ratio (breadth), an unweighted measure of all stocks, has fallen to levels not seen since 1985, when the Dow was in the 1300s.

One guideline for analysing very long term stock market action that's been reliable for most of this century has been the dividend yield on the Dow Jones Industrials. At bull market tops, such as in 1987 and the recent record highs, the yield usually drops to 3% or a little less. At bear market bottoms, such as 1974 and 1982, the Dow yield rises to 6% or more. I believe we're currently in a down-cycle which started with the yield well below 3% and will continue until real fear and panic liquidation grips the market. The Dow yield is presently in the 4% range, so I think we have quite a way to go both numerically and psychologically. If no dividend cuts were to occur, a Dow yield of 6% would require the Dow to fall to the 1750 range. In a recession, of course, dividend decreases are the norm, so an even lower target would be expected.

Interestingly, two other unrelated measures suggest a target in the same range. Bear markets have a tendency to erase half the gains of the preceding bull market. If you look at the entire 15 year bull market that carried to Dow from 577 in 1974 to 3000 in 1990, the halfway point is in the 1780s. Finally, the crash low of 1987 was 1738, with a secondary low of 1766 recorded in December of 1987. These lows have not been revisited in the subsequent years. A chartist (and yes, experience has taught me not to disregard this tool for comprehending mass human behaviour as reflected by the markets) would say there is “strong support” in the mid 1700s.

Then there is this perspective….

Even if you discount all of this analysis as utter mumbo-jumbo, I'd still urge deferring any stock buy-back on the simple grounds that it's wise to conserve cash at a time when there are so many economic uncertainties. If you believe I may be right about the bear market and expect it to follow the historical pattern of past bear markets, then we should keep the cash in the money bin until the bear brings prices down.

Bear markets, once underway, tend to accelerate and exceed even the

most carefully calculated downside targets. The best indication of

the end of a bear market is when the market refuses to go down further

even in the face of the bleakest of news. Consequently, numerical

(or, some would say, numerological) targets, however calculated, are

no substitute for informed judgement based on consideration of all

relevant factors. That said, if Autodesk stock is today around $45

and the Dow is in the vicinity of 2500, given the beta of our stock

and the historical tendency of smaller stocks to fall further in a

bear market, I'd expect us to be able to repurchase our stock between

$20 and $30 per share at a bear market bottom.![]() This is a

case where being wrong doesn't cost very much. If our stock starts

soaring again, we wouldn't want to repurchase it but then there

wouldn't be any reason to! As long as a downtrend is in effect, I'd

be inclined to continue to ride it down so as to get the most stock

for the funds we devote to the repurchase.

This is a

case where being wrong doesn't cost very much. If our stock starts

soaring again, we wouldn't want to repurchase it but then there

wouldn't be any reason to! As long as a downtrend is in effect, I'd

be inclined to continue to ride it down so as to get the most stock

for the funds we devote to the repurchase.

I don't think it would be wise to make any large real estate purchases at this time (in particular, buying a campus site and the initial buildings there). Every indication is that the real estate market is in a downtrend, with no immediate end in sight. Given the overall debt crisis and the amount of highly-leveraged speculative real estate that could come on the market in a real credit crunch, we may be seeing only the beginning of a prolonged bloodletting in California real estate. Even if things get no worse than they presently are in Texas, that's still quite a way from California's present situation.

Conserving cash is the primary motivation. Not wishing to buy into a bear market in real estate is a secondary consideration. Even if you reject both of these rationales, however, I still think we'd be well served by leasing rather than buying simply on the standpoint that Autodesk is a software company, not a real estate company. Why dilute our business focus by starting up a property management operation, even if for our own exclusive use? If the argument in favour of buying is that we would make money by owning our facilities, then I'd suggest that rationale deserves even closer scrutiny because it counsels speculation in California commercial property as the justification for commitment of Autodesk's funds.

I'm not against speculation. But I believe in speculating in things

that are likely to go up. I don't think California real

estate in 1990 would be on anybody's hot list.![]()

This was a good idea when I recommended it mid-1988. It would have been seen, in retrospect, as an enormously shrewd strategic move had we implemented it as we'd discussed around the time the dollar hit its peak in 1989. It's still the wisest course, in my opinion, as the dollar plunges to new daily lows.

This is not a speculative strategy designed to profit from exchange rate instabilities. It is not a bet against the future of the United States. It is simply a prudent and appropriate deployment of the liquid assets of a multinational company which derives close to half its sales and a majority of its recent growth from markets outside the United States.

Once we implement effective currency diversification, we can ignore all the headlines about the dollar plunging and soaring. We'll know that Autodesk's ability to compete in each of its markets is unaffected by such news. As long as an overwhelming percentage of our assets are concentrated in one currency, we're held hostage to the monetary policy of the central bank that controls it. Given the experience of the last two decades, this is simply unwise.

Autodesk has done an excellent job in balancing concern for domestic markets with the attention the headquarters organisation must give to the health of the company's operations around the world. We must continue to do this, even if problems in the domestic market threaten to divert our attentions from the global performance of the company.

We've performed superbly overseas, but we should bear in mind that on a GNP basis, if our position in global markets equaled that in the United States, U.S. sales would be only 33% of global sales, not about half. The relative technological, commercial, and political importance of the United States has been eroding for more than forty years, and there's no reason to believe this will end at any time in the near future—particularly in a multi-polar world increasingly focused on competitiveness in a global market economy. Autodesk should deploy its efforts in various markets in proportion to their present and estimated future revenue prospects, not based on arbitrary divisions into territories.

Our products must continue to reflect the international nature of our market. Medium term goals to this end should include, in my opinion, the ability for any Autodesk customer in the world to order and obtain in a timely fashion any of the language editions of our products (in other words, I should be able to order a Czech language AutoCAD from my local Autodesk dealer in Osaka), and to support within AutoCAD and include with the standard product fonts that support all human languages in which engineering drawings are prepared.

The last thing we want to do is follow the usual high-tech company pattern of continuing to grow right into the crunch, then have to painfully reverse course and cut back. Now's the time to put a lid on hiring, shrink as appropriate by attrition, and lean down the organisation for uncertain times. It's always much easier to turn the spigot back on than mop up the floor after the tub's overflowed.

Based on my own personal leading indicator: the percentage of the job opening bulletin board in 2320/1 covered by paper, I suspect that such a policy is already in effect. Very wise—and appropriate until domestic sales growth resumes.

One of the reasons I'm uneasy about the campus proposal stems from the same source. I'm not sure where we expect the growth to come from that justifies the employment figures the campus is intended to accommodate. And how soon do we have to decide, particularly in a collapsing real estate market that appears to favour the patient buyer?

Nobody hopes for a collapse of our reseller channel. But what if it happens? Management must manage. Even if you assign a small probability to the scenario I've described which could leave us in short order without a channel for moving our products, wouldn't it be wise to assign a commensurately small working group to explore alternatives should that come to pass? What I envision is the preparation, discussion, and adoption of several contingency plans for reacting to anticipated problems in the dealer community. What is important is that these plans be sufficiently specific and well thought out so one could be implemented merely by disseminating it throughout the company and giving instructions to execute it.

I do not wish to prescribe the strategies such plans might recommend. They could range from utter abandonment of the reseller channel and a transition to direct-mail and telemarketing with a greatly expanded direct support operation to a program of equity investment in key resellers combined with pricing changes intended to guarantee the viability of the surviving distribution organisations.

Thinking about this today, before the problems become severe, will not exacerbate the situation any more than drawing up a will hastens your demise. It's far better to worry about a potential crisis and then discard a contingency plan as unneeded than to be forced to react without adequate time for reflection on the consequences of various courses of action.

In a market confused by OS/2 vs. Windows, RISC vs. CISC, MCA vs. EISA, and so tiresomely on, it may be necessary for Autodesk to forgo our traditional neutrality and provide some real guidance to our user and reseller communities about what makes the most sense.

Clearly, we wouldn't want to do this in a way that impaired our relationships with a wide variety of vendors, but we not only bear a responsibility to our customers to provide an honest evaluation of their alternatives in assembling a system to run our software, it's in our own best interest to have the majority of our customers equipped with optimal hardware and software configurations for our products.

If no better alternative presents itself, and you believe this problem is as serious as I suspect it is, I'd recommend that we create another Autodesk Distinguished Fellow of a heavy-duty programmer and charge that fella with going out into the real world and telling the truth about hardware and software for doing CAD.

One specific consequence of the confusion in the PC market appears clear: users are moving to Microsoft Windows in droves. It provides many of the apparent benefits of OS/2 and the Macintosh at a low marginal cost. We've been caught without an AutoCAD for Windows, and we should remedy this omission as soon as possible. My understanding is that no technical barrier prevents us from immediately starting a Windows port with the intent of shipping a Release 11 Windows version within the next 12 months. The Windows AutoCAD would run in 80386 protected mode under Windows, as Mathematica presently does, and would have performance comparable to that of AutoCAD 386.

With the re-architecting of the internals of AutoCAD anticipated for Release 12 (the OOPS project), Autodesk will be in a position to take a bold step which, if successful, may ensure the preeminence of AutoCAD for the next quarter century, greatly accelerate the pace of AutoCAD development, and establish a new paradigm for the relationship between a PC software vendor and its customers which our competitors will find difficult to emulate.

I'm talking about making the source code for AutoCAD available, and before you stop reading, let me explain the reasons for such a move as well as the means I've come up with for testing the concept without incurring any substantial risk.

Why distribute source code? Because we're greedy, and we'll make more money that way. Consider Unix. Unix source code has always been available. In the early days, when Unix was primarily used within universities, AT&T's licensing policies made source available to most users of the system. As a consequence, an entire generation of computer science students came to think of all operating systems in terms of Unix. I believe that the dominance of Unix in the workstation market today is directly traceable to that policy. Tens of thousands of people learned Unix as their first system, and learned it in depth as only access to the source can enable. They learned how to adapt Unix for other machines and applications. By thinking of all operating systems within the Unix paradigm, they demoted those other systems to second class status and made it difficult for any of them to assail the position Unix had achieved, not just in the market, but in the very minds of the decision makers.

We can do the same thing with CAD. Today, AutoCAD has become synonymous with CAD, but only from the perspective of the user. By making source available, the very implementation of AutoCAD will become the paradigm for how CAD systems are built. Universities will use AutoCAD to teach computer graphics software development, and a generation will come to think of graphics software in the language we've defined—AutoCAD. But that's not all.

For those fanatically dedicated users will also be doing things to their AutoCAD source code. They'll be implementing extensions, replacing antiquated algorithms with the latest concepts from current research, investigating new ideas in user interfaces, and they'll make all of these developments available to us. Why? Well, because that's part of the source license but, more importantly, because they want the recognition that comes from having a vendor adopt their work. If this seems like fantasy, please recall that most software developers at Autodesk are using workstations that run an operating system developed by AT&T, provided in source form to its customers, one of whom, the University of California at Berkeley, extended it into the operating system of choice for workstations and handed those changes back to AT&T.

All of the founders of Autodesk learned their trade by working on software provided in source code form by its vendors. I think any of them will readily confirm that such experience tends to make one view all subsequent systems in terms of the one you've mastered at the source level. Within five years, a major role of our software development department may be evaluating various user-developed extensions to AutoCAD and integrating them into an ever-changing product.

But isn't this giving away the store? Not at all. First, if somebody wants to steal AutoCAD, starting with the source code is a pretty idiotic way to go about it, compared to just copying the distribution discs. There's no need to worry about disclosing any deep, dark proprietary information either, since AutoCAD doesn't really contain any. All of the algorithms used in AutoCAD are available in the open literature and for the most part are used by all CAD systems. In any case, a creative user can always reverse-engineer technology without source code, as the customers who've decoded the .DWG file format have demonstrated.

But what about serialisation, hardware lock code, and so on? Release 12 holds the answers to these concerns. The OOPS mechanism allows code to be written in the same manner regardless of whether it is within what we now call the “AutoCAD core” or outside in an “application.” By defining the core as a very small module, provided without source, containing the security-related code, and most of the rest of AutoCAD as outside the core, we can provide source to all the portions of AutoCAD a legitimate user might want to examine or modify without compromising the security we have today in the core code. There is no efficiency penalty in structuring the program in this manner, so it's largely a question of where we choose to draw the line.

Do we really want users to see how awful some parts of AutoCAD are? Absolutely! Then some wild-eyed kid at some backwater college will rewrite the OFFSET command so it really works right and mail it in. This really happens. Trust me.

But what if I'm wrong? How can we justify taking such a risk? Simple, try it out on a little piece first. In Release 12 we have the opportunity to separate IGES and dimensioning, two of the most-modified sections of AutoCAD, portions that have accounted for an endless series of user requests for change, and experiment with source licensing them. Clearly, nobody is going to be able to knock off AutoCAD by having access to these pieces. Let's go ahead and make IGES and dimensioning applications at the OOPS level (something that makes sense in any case, from purely technical considerations within the product), and then dip our toe in the water by introducing source licenses for them at, say, $1500 for both. The educational price would be something like $50. (My long term goal for a full AutoCAD source license price would be equal to the runtime license. For example, $3500 for the binaries and another $3500 for the source. All source licensing sales and administration would be direct, and hence all sales would be at full list price.)

Yes, indeed, this could generate additional revenue, couldn't

it?![]()

There's one good thing you can say about recessions. They sure do make hardware cheap! The 1974–75 recession was a major contributor to the subsequent personal computer explosion in a very simple yet often overlooked way: at the end of that downturn, the price of logic circuits per gate had dropped from dollars to pennies. Projects that previously required the financial resources of a substantial company were now within the purview of individual mad scientists in drafty basements. I know. I was one.

The semiconductor business is an analytical economist's dream. It has a huge capital spending component and long lead times, a large intellectual capital contribution that's related to R&D spending and the ability to translate it into marketable products, and close to zero material costs. These fundamentals have interesting consequences in a recession.

The R&D costs for the products you're currently making are already sunk and can be recovered only by selling more products. The cost of operating the production line is dominated by amortisation of capital equipment already in place and direct labour—both unrelated to the volume of products produced. Incremental improvements in yield reduce costs and are sought on that basis alone. The cumulative effect of these fundamentals is very much like a replicator that's swallowed its shut-off switch. With the factory accounting for a constant fixed cost every month, all incentives are toward increasing output. Increased output drives the unit price down, forcing competitors to further streamline their own operations, and so on.

The nature of semiconductor fabrication technology causes memory circuits to lead all others in complexity at constant cost. A software company whose products have been constrained by limited memory for the better part of a decade would be wise to ponder the consequences of a memory price crash. (Or, should no recession eventuate, a slower yet equally inevitable erosion of memory prices.)

When Autodesk was founded, 64K memory was the standard complement in the personal computers of the time. I recall when I first heard that the IBM PC version of AutoCAD would require 128K of RAM. “How profligate,” I thought, “Why can't they fit it into 64K like real programmers?”

At that time, 16K RAM chips were giving way to the 64K RAM generation. Since then, we've seen the 64K RAM supplanted by the 256K RAM, and the 256K pass the torch to the 1 Mb chip. Recently, 4 Mb RAM chips have begun to appear in quantity with prototypes of its successors, the 16 and 64 Mb chips already described in research papers at the various solid state circuit conferences.

As we sit and struggle with MS-DOS and its one megabyte address space limitation, it's worth contemplating the implications of a world that's adopted the 4 Mb or 16 Mb RAM as the standard memory component. Most of the microprocessors in use today have a 32 bit memory bus: each memory access reads or writes four bytes at once. Hence, when that memory is composed of chips of a given capacity measured in bits, the memory expansion increment in bytes is four times the chip capacity in bits.

Think about it. As 4 Mb RAM chips achieve price parity and begin to displace the 1 Mb generation, the minimum memory configuration of a 32 bit bus processor such as an 80386 or 80486 will be 16 megabytes, and memory expansion will be in increments of 16 megabytes. When the 16 megabyte chips supplant the 4 Mb chips, memory will start at 64 megabytes and grow in steps of that size.

Memory on this scale truly changes everything. CAD moves from an application that strains the limit of every resource on the system to a modest user of abundant computing resources. Anticipating the widespread availability of computing power in this class (which will happen regardless of the economic environment, but perhaps later rather than sooner), Autodesk should devote resources within the Advanced Technology division to defining the design tools made possible by such hardware configurations and undertaking their development in order to deliver them as soon as the required hardware becomes available to our customers.

Never since our company was formed has the immediate future of the economic and political system within which Autodesk operates been so uncertain. Credible, rational alternatives for the next several years range from global peace and prosperity as democracy and free markets sweep the globe to financial panic, economic collapse, and World War IV. Whatever may come, Autodesk is well-prepared. We have the financial strength to withstand hard times, the cautious and prudent approach to risk taking needed to protect that strength, a commanding position in an enduring market that is central to industrial development, and the international and industrial diversification to mitigate localised or sector-specific downturns.

What Autodesk must do to survive difficult economic times is largely the same things we do to take advantage of periods of rapid growth—making the best products and providing the best service to our customers. Considering the recommendations in this paper and implementing those judged to be wise should further insulate Autodesk from unpleasant surprises and allow us to remain focused on the truly important things. The principles that have brought Autodesk the strength to face the future with equanimity will guide us through that future to even greater success.

|

|