|

|

My hunger serves me instead of a clock.—Jonathan Swift, Polite Conversation, 1738

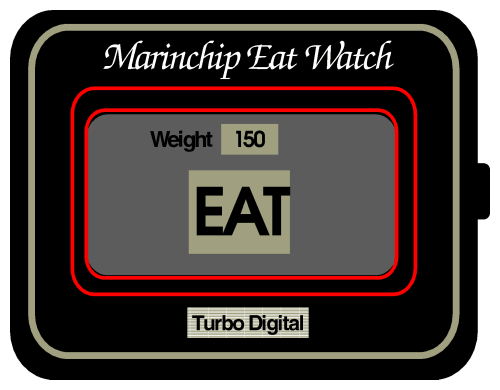

Wouldn't it be great if you could visit your local purveyor of

electronic marvels and purchase one of these?

You strap it on your wrist, set it for the weight you want to be, then rely on it to tell you when to eat and when to stop. Whenever it says EAT, just chow down on anything you like until EAT goes out. Obviously the EAT indicator will stay on longer if you're munchin' cabbage instead of chugging München's finest beer.

As long as you heeded the Eat Watch, you'd attain and maintain whatever weight you set it to. If you ate the wrong foods or had your meals on an odd schedule you might be hungry, but you'd never be fat. And, with the eat watch guiding you, you'd rapidly find a meal schedule and makeup that banished hunger forever.

The eat watch wouldn't control you any more than a regular watch makes you get to work on time. You can ignore either, if you wish. You decide, based on the information from the watch, what to do.

Some people are born with a natural, built-in eat watch. You and I either don't have one, or else it's busted. But instead of moping about bemoaning our limitations, why not get an eat watch and be done with it?

You can't buy an eat watch in the store, at least not yet. But you can make one that works every bit as well. It isn't a gadget you wear on your wrist; it's a simple technique you can work with pencil and paper or with a personal computer. It tells you same thing: when to eat and when to stop eating. The eat watch you'll discover in this book is simple to work, easy to use, and highly effective in permanently controlling your weight.

The next few chapters lay the background for building an eat watch. The principles on which the eat watch is based are subtle and, although they've been used in engineering for decades, seldom are mentioned in conjunction with weight control. I'll explain them in detail. The road to understanding the eat watch is a long but interesting one. When we reach its end, you'll not only know how to use an eat watch, but how and why it works. Then you'll have the confidence, founded on knowledge, that your weight is totally and permanently under your control.

If people didn't eat except when their bodies needed food, nobody would be overweight. What a wonderful world it would be! (Of course, there wouldn't be a market for diet books….)

Hunger is supposed to tell us when it's time to eat, but in the modern world, we rarely rely on this message from our bodies. We eat certain meals on a given schedule, with family and friends. And, while hunger tells us when to eat, there isn't a corresponding signal that says we've had enough. Only when the scale begins to rack up extra pounds and the belt seems to need another notch do we realise the cumulative effect of a little too much food every day.

As long as you aren't hungry, you're probably getting enough food, but how do you keep from eating too much? What's needed, along with food, is feedback—information that tells how you're doing—when to eat and when to stop: the message of the eat watch.

I believe one of the main reasons some people have trouble controlling their weight while others manage it effortlessly is that there's a broken feedback circuit in those of us who tend to overweight. Our bodies don't tell us “enough already!”, while our slim and trim comrades, born with a built-in eat watch, always know when to hang up the nosebag.

But, hey—no problem! Back when we were all hunter-gatherers, people with crummy eyesight probably didn't live very long. It's hard to throw a spear when you can't even see the end of your arm. Along comes technology and zap!!!: eyeglasses fixed that problem once and for all. Actually, it's tilted the other way these days; if I weren't blind as a cinder block without my glasses, I'd probably have been sent to 'Nam.

So it is with the eat watch. If you weren't born with one, just get one, strap it on your wrist, and get on with life.

Controlling your weight provides an interesting window on the enigma of sentience, the distinction between mind and body. Weight control involves the body at the simplest level; eat more and gain weight, eat less and lose it. Yet the reasons we become overweight and the difficulties we have in losing weight often stem from the subtleties of psychology rather than the mechanics of mitochondria.

To control your weight, you need only eat the right amount. To eat the right amount, not just this month or next month, but for the rest of your life, you need not only the information—the display on the face of the eat watch—to know what's the “right amount”; you need an incentive to follow that guidance. Wearing a watch doesn't make you a punctual person, but it provides the information you need to be one, if that's your wish.

This incentive is the “motivation to control your weight,” often simplistically deemed “will power.” Where can you find this motivation, especially if you've tried diet after diet and failed time after time? This book will help you to find the motivation in the only place it can be found, within yourself, by laying out a program that makes the steps to success easy and the thought of failure or backsliding difficult to contemplate.

This constitutes manipulation, but manipulation's OK as long as you're manipulating yourself. After all, in order to manipulate somebody you have to understand them, and who do you understand better than yourself? The goal is empowerment: the sudden realisation, “Hey, this isn't hard at all! I can do this!” It is such discoveries that give us the confidence and courage to go onward to greater challenges. The course of a life is often charted by such milestones of empowerment. Manipulation in the pursuit of empowerment is no vice.

Latent within you is the power to control your weight for the rest of your life. All you need to do is realise that your weight is under your conscious control. With that knowledge, you can peel off your excess weight and achieve physical fitness. Once you've accomplished those goals, you'll be in a position to make them central to your self-image.

Less than 12 months from now, new people you meet will be incapable of imagining you as overweight. Next year, you'll be able to run up four flights of stairs and scarcely notice the exertion. If, like me, you've been overweight most of your life, you're about to partake of a new and rich part of the human experience: the exultation of living in a healthy animal body.

Once you've experienced the joy, the confidence, and the feeling of power that success entails, you'll never consider giving it up—not even for that extra slice of pie.

Recently, the word “hacker” has fallen into disrepute, coming to signify in the popular media the perpetrators of various forms of computer-aided crime. But most of the people who call themselves hackers, who have proudly borne that title since the 1950's, are not criminals—in fact many are among the intellectual and entrepreneurial elite of their generations.

The word “hacker” and the culture it connotes is too rich to sacrifice on the altar of the evening news. Bob Bickford, computer and video guru, defined the true essence of the hacker as “Any person who derives joy from discovering ways to circumvent limitations.”

Indeed…. Well, what better limitations to circumvent than ones you've endured all your life? For the last few years, I've spent a weekend every Fall attending the “Hackers Conference”: a gathering of computer folk who exult in seeing limitations transcended through creativity. A commemorative T shirt is designed for each conference, so when you fill out your application, you have to say what size you wear. Hackers being hackers, it's inevitable that somebody will enter these data into a computer and analyse them.

The statistics are remarkable. We're talking megayards here; one wonders what the numbers would be if T-shirts came in Extra-Extra-Large, Jumbo, Gigantic, Colossal, Planetary, and Incipient Gravitational Collapse sizes as well as the usual S, M, L, and XL.

People who thrive on unscrewing the inscrutable—figuring out how complicated systems work and controlling them—sometimes fail to apply those very techniques to maintaining their own health. How strange to on the one hand excel at your life's work and on the other, XL in girth.

But not that strange, really. I've been there. For decades I believed controlling my weight was impossible, too painful to contemplate, or incompatible with the way I chose to live my life. I'd convinced myself that the only people who were physically fit were lawyers and other parasitic dweebs who, not forced to earn an honest living, had the time for hours of pumping various odd machines or jogging in the middle of the road while hard-working, decent folks were trying to get to work.

Most extraordinary things are done by ordinary people who never knew what they were attempting was “impossible.” Hackers have seen this happen again and again; many of the most significant innovations in computing have been made by individuals or small groups, working alone, attempting tasks the mainstream considered impossible or not worth trying.

Once you possess the power to circumvent limitations, to control things most people consider immutable, you're liberated from the tyranny of events. You're no longer an observer; you're in command. You've become a hacker. This book is about one simple, humble thing: getting control of your weight and health. By circumventing the limitations that made you overweight in the first place and keep you that way, you're hacking the most complicated and subtle system in the world: your own human body. Weight control—what a hack! Once you realise you can hack your weight, who can imagine what you will turn to next?

In every era, each culture defines itself in terms of the heroes it admires. That, in turn, determines the mindset and aspirations of the generation whose values are formed during that time. For past generations explorers, military men, inventors, financiers, and statesmen have filled the role of hero. I believe that our time is the age of the manager. The MBA degree, a credential that qualifies one to administer by analysing and manipulating financial aggregates, has become the most prized ticket to advancement in the United States. The values managers regard most highly: competence, professionalism, punctuality, and communication skills have been enshrined as the path to success and adopted by millions.

The cult of management, for that is what it is, pervades the culture which is its host. In time, it will be seen to be as naive as the ephemeral enthusiasms that preceded and will, undoubtedly, supplant it in due course. But now, at the height of its hold, it's important to distinguish managing a problem from fixing it, for these are very different acts: one is a process, the other an event. Solving a problem often requires a bit of both.

“Management must manage” was the motto of Harold Geneen, who built ITT from an obscure international telephone company into the prototype of the multinational conglomerate. What Geneen meant by this is that the art of the manager is coming to terms with whatever situations develop in the course of running a business and choosing the course of action that makes the best of each.

The world of the manager is one of problems and opportunities. Problems are to be managed; one must understand the nature of the problem, amass resources adequate to deal with it, and “work the problem” on an ongoing basis. Opportunities are merely problems that promise to pay off after sufficient work.

Managers are not schooled in radical change. The elimination of entire industries and their replacement with others, the obsolescence of established products in periods measured in months, the consequences of continued exponential growth in technology are all foreign to the manager. Presented with a problem, an expert manager can quickly grasp its essence and begin to formulate a plan to manage the problem on an ongoing basis.

But what if the problem can be fixed? This is not the domain of the manager.

Engineers, derided as “nerds” and “techies” in the age of management, are taught not to manage problems but to fix them. Faced with a problem, an engineer strives to determine its cause and find ways to make the problem go away, once and for all.

An engineer believes most problems have solutions. A solution might not be achievable in the short term, but he's sure somewhere, somehow, inside every problem there lurks a solution. The engineer isn't interested in building an organisation to cope with the problem. Instead, the engineer studies the problem in the hope of finding its root cause. Once that's known, a remedy may become apparent which eliminates the need to manage the problem, which no longer exists.

Most of the technological achievements of the modern world are built on billions of little fixes to billions of little problems, found through this process of engineering. And yet the engineer's faith in fixes often blinds him to the fact that many problems, especially those involving people, don't have the kind of complete, permanent solutions he seeks.

Many difficult and complicated problems require a combination of the skills of management and the insights of engineering. Yet often, the difficulty managers and engineers have in understanding each other's view of the world thwarts the melding of their skills to truly solve a problem. In isolation, a manager can feel rewarded watching the organisation he created to “work the problem” grow larger and more important. Rewardingly occupied too, is the engineer who finds “fix” after “fix,” each revealing another aspect of the problem that requires yet another fix. Neither realises, in their absorption in doing what they love, that the problem is still there and continues to cause difficulties.

The development of the U.S. telephone network in the twentieth century provides an excellent example of how management and engineering can, together, solve problems. In the year 1900 there were about a million telephones in the country. By 1985 more than 135 million were installed. Building a system to connect every residence and business across a continent, providing service so reliable it becomes taken for granted, is one of the most outstanding management achievements of all time. Yet it never could have happened without continuing engineering developments to surmount obstacles which otherwise would have curtailed its growth: problems no amount of management, however competent, could have ameliorated alone.

Consider: in 1902 every thousand telephones required 22 operators. The Bell System employed 30,000 operators then, making connections among the 1.3 million telephones that existed. Had this ratio remained constant, the dream of a telephone in every house, on every desk in every business, would have remained only a dream for it would have required, by 1985, three million operators plugging and unplugging cables just to keep the phones working. About 3% of the entire labour force would be telephone operators. Even if that many could somehow be hired and trained, the salary costs would price phone service out of reach of most people.

No amount of management could overcome this limitation. But a series of incremental engineering fixes, starting with automated switchboards for human operators, then direct dial telephones, and finally direct worldwide dialing reduced the demand for operators to a level where universal telephone service became a reality. The managers wisely realised they needed an engineering fix, funded the search for one, and when it was found, managed the transition to the new system and its ongoing operation thereafter.

The engineers, likewise, realised that while they could fix a large part of the problem, they couldn't do it all. Had they sought to eliminate operators entirely, they would never have found a workable system. Instead, they automated what they could and relied on a well-managed organisation of human beings to handle the balance. Indeed, the number of operators employed by the Bell System has grown steadily over the years, reaching 160,000 by 1970. But the engineering fixes had, through time, reduced the requirement from 22 operators per thousand phones to about 1.7.

Management in isolation struggles with constraints that can frequently be eliminated. Engineering in isolation seeks permanent fixes which sometimes don't exist and, even when found, often require an ongoing effort to put into place and maintain. Each needs the other to truly solve a problem. So it is with controlling your weight. First, you must fix the problem of not knowing when and how much to eat. As long as you lack that essential information, you'll never get anywhere. Then, you have to use that information to permanently manage your weight.

Diet books reflect the division between engineers and managers. When they focus on a “magic diet,” they're seeking a quick fix. When they preach about “changing your whole lifestyle,” they're counseling endless coping with a broken system. This book presents an engineering fix to the underlying problem, then builds a management program upon it to truly solve the problem of being overweight.

There's a lot of nonsense floating around regarding exercise and weight control. The only way to lose weight is to eat less than your body burns. Period. Exercising causes your body to burn more, but few people have the time or inclination to exercise enough to make a big difference. An hour of jogging is worth about one Cheese Whopper. Now, are you going to really spend an hour on the road every day just to burn off that extra burger?

You don't exercise to lose weight (although it certainly helps). You exercise because you'll live longer and you'll feel better. When I started to control my weight, I had no intention of getting into exercise at all. As the pounds peeled off and I felt better and better, I decided to design an exercise plan built on the same principles that made the diet plan succeed.

This exercise plan is presented for your consideration in a subsequent chapter. Even if you're dead set against the very concept of physical exertion, please read the introduction to that chapter. Like me, you've probably always thought of exercise as wasted time—precious minutes squandered in unpleasant activities. I think you'll find, as I did, that exercise actually increases the time you'll have to accomplish whatever matters in your life.

If you buy that argument, give the exercise plan a shot. Like the diet plan, it's calculated to motivate you to succeed, manipulate you to keep you going, and provide the feedback you need to let you know how far you've come. If you follow the plan carefully, you'll never be in pain, be exhausted, or ever spend more than 15 minutes a day on it.

|

|