« May 2019 | Main | July 2019 »

Friday, June 28, 2019

Reading List: Diabolical

- Yiannopoulos, Milo. Diabolical. New York: Bombardier Books, 2018. ISBN 978-1-64293-163-1.

-

Milo Yiannopoulos has a well-deserved and hard-earned reputation as a

controversialist, inciter of outrage, and offender of all the right

people. His acid wit and mockery of those amply deserving it causes

some to dismiss what he says when he's deadly serious about

something, as he is in this impassioned book about the deep

corruption in the Roman Catholic church and its seeming abandonment

of its historic mission as a bastion of the Christian values

which made the West the West. It is an earnest plea for a new

religious revival, from the bottom up, to rid the Church of

its ageing, social justice indoctrinated hierarchy which, if not

entirely homosexual, has tolerated widespread infiltration of

the priesthood by sexually active homosexual men who have

indulged their attraction to underage (but almost always

post-pubescent) boys, and has been complicit in covering up these scandals

and allowing egregious offenders to escape discipline and

continue their predatory behaviour for many years.

Ever since emerging as a public figure, Yiannopoulos has had a target

on his back. A young, handsome (he may prefer “fabulous”),

literate, well-spoken, quick-witted, funny, flaming homosexual,

Roman Catholic, libertarian-conservative, pro-Brexit, pro-Trump,

prolific author and speaker who can fill auditoriums on

college campuses and simultaneously entertain and educate his audiences,

willing to debate the most vociferous of opponents, and who

has the slaver Left's number and is aware of their vulnerability

just at what they imagined was the moment of triumph, is the stuff

of nightmares to those who count on ignorant legions of dim

followers capable of little more than chanting rhyming slogans

and littering. He had to be silenced, and to a large extent,

he has been. But, like the Terminator, he's back, and he's aiming

higher: for the Vatican.

It was a remarkable judo throw the slavers and their media

accomplices on the left and “respectable right”

used to rid themselves of this turbulent pest. The

virtuosos of victimology managed to use the author's having

been a victim of clerical sexual abuse, and spoken

candidly about it, to effectively de-platform, de-monetise,

disemploy, and silence him in the public sphere by proclaiming

him a defender of pædophilia (which has nothing to do

with the phenomenon he was discussing and of which he was a

victim: homosexual exploitation of post-pubescent boys).

The author devotes a chapter to his personal experience and how

it paralleled that of others. At the same time, he draws a

distinction between what happened to him and the rampant

homosexuality in some seminaries and serial abuse by prelates in

positions of authority and its being condoned and covered up

by the hierarchy. He traces the blame all the way to the

current Pope, whose collectivist and social justice credentials

were apparent to everybody before his selection. Regrettably,

he concludes, Catholics must simply wait for the Pope to die

or retire, while laying the ground for a revival and restoration

of the faith which will drive the choice of his successor.

Other chapters discuss the corrosive influence of so-called

“feminism” on the Church and how it has corrupted

what was once a manly warrior creed that rolled back the

scourge of Islam when it threatened civilisation in Europe

and is needed now more than ever after politicians seemingly

bent on societal suicide have opened the gates to the invaders;

how utterly useless and clueless the legacy media are in

covering anything relating to religion (a New York Times

reporter asked First Things editor Fr Richard

John Neuhaus what he made

of the fact that the newly elected pope was “also”

going to be named the bishop of Rome); and how the rejection

and collapse of Christianity as a pillar of the West risks

its replacement with race as the central identity of the culture.

The final chapter quotes Chesterton

(from Heretics, 1905),

Everything else in the modern world is of Christian origin, even everything that seems most anti-Christian. The French Revolution is of Christian origin. The newspaper is of Christian origin. The anarchists are of Christian origin. Physical science is of Christian origin. The attack on Christianity is of Christian origin. There is one thing, and one thing only, in existence at the present day which can in any sense accurately be said to be of pagan origin, and that is Christianity.

Much more is at stake than one sect (albeit the largest) of Christianity. The infiltration, subversion, and overt attacks on the Roman Catholic church are an assault upon an institution which has been central to Western civilisation for two millennia. If it falls, and it is falling, in large part due to self-inflicted wounds, the forces of darkness will be coming for the smaller targets next. Whatever your religion, or whether you have one or not, collapse of one of the three pillars of our cultural identity is something to worry about and work to prevent. In the author's words, “What few on the political Right have grasped is that the most important component in this trifecta isn't capitalism, or even democracy, but Christianity.” With all three under assault from all sides, this book makes an eloquent argument to secular free marketeers and champions of consensual government not to ignore the cultural substrate which allowed both to emerge and flourish.

Wednesday, June 26, 2019

Reading List: The Voyage of the Iron Dragon

- Kroese, Robert. The Voyage of the Iron Dragon. Grand Rapids MI: St. Culain Press, 2019. ISBN 978-1-7982-3431-0.

-

This is the third and final volume in the Iron Dragon trilogy

which began with The Dream of the Iron

Dragon (August 2018) and

continued in The Dawn of the Iron Dragon

(May 2019). When reading a series of books I've discovered,

I usually space them out to enjoy them over time, but the second book

of this trilogy left its characters in such a dire pickle I just

couldn't wait to see how the author managed to wrap up the story in

just one more book and dove right in to the concluding volume. It

is a satisfying end to the saga, albeit in some places seeming

rushed compared to the more deliberate development of the story and

characters in the first two books.

First of all, this note. Despite being published in three

books, this is one huge, sprawling story which stretches over

more than a thousand pages, decades of time, and locations as

far-flung as Constantinople, Iceland, the Caribbean, and North

America, and in addition to their cultures, we have human

spacefarers from the future, Vikings, and an alien race called

the Cho-ta'an bent on exterminating humans from the galaxy. You

should read the three books in order: Dream,

Dawn, and Voyage. If you start in the

middle, despite the second and third volumes' having a brief

summary of the story so far, you'll be completely lost as to who

the characters are, what they're trying to do, and how they

ended up pursuing the desperate and seemingly impossible task in

which they are engaged (building an Earth-orbital manned

spacecraft in the middle ages while leaving no historical traces

of their activity which later generations of humans might find).

“Read the whole thing,” in order. It's worth it.

With the devastating events which concluded the second volume,

the spacemen are faced with an even more daunting challenge than that

in which they were previously engaged, and with far less

confidence of success in their mission of saving humanity in its

war for survival against the Cho-ta'an more than 1500 years in

their future. As this book begins, more than two decades have

passed since the spacemen crashed on Earth. They have patiently

been building up the infrastructure required to build their

rocket, establishing mining, logging, materials processing, and

manufacturing at a far-flung series of camps all linked together

by Viking-built and -crewed oceangoing ships. Just as important

as tools and materials is human capital: the spacemen have had

to set up an ongoing programme to recruit, educate, and train

the scientists, engineers, technicians, drafters, managers, and

tradespeople of all kinds needed for a 20th century aerospace

project, all in a time when only a tiny fraction of the

population is literate, and they have reluctantly made peace

with the Viking way of “recruiting” the people they

need.

The difficulty of all of this is compounded by the need

to operate in absolute secrecy. Experience has taught

the spacemen that, having inadvertently

travelled into Earth's past, history cannot be changed.

Consequently, nothing they do can interfere in any way with

the course of recorded human history because that would

conflict with what actually happened and would therefore

be doomed to failure. And in addition, some Cho-ta'an

who landed on Earth may still be alive and bent on

stopping their project. While they must work technological

miracles to have a slim chance of saving humanity, the Cho-ta'an

need only thwart them in any one of a multitude of ways to

win. Their only hope is to disappear.

The story is one of dogged persistence, ingenuity in the face of

formidable obstacles everywhere; dealing with adversaries as

varied as Viking chieftains, the Vatican, Cho-ta'an aliens, and

native American tribes; epic battles; disheartening setbacks;

and inspiring triumphs. It is a heroic story on a grand scale,

worthy of inclusion among the great epics of science fiction's

earlier golden ages.

When it comes to twentieth century rocket engineering, there are

a number of goofs and misconceptions in the story, almost all of

which could have been remedied without any impact on the plot.

Although they aren't precisely plot spoilers, I'll take them

behind the curtain for space-nerd readers who wish to spot them

for themselves without foreknowledge.

Spoiler warning: Plot and/or ending details follow.Despite the minor quibbles in the spoiler section (which do not detract in any way from enjoyment of the tale), this is a rollicking good adventure and satisfying conclusion to the Iron Dragon saga. It seemed to me that the last part of the story was somewhat rushed and could have easily occupied another full book, but the author promised us a trilogy and that's what he delivered, so fair enough. In terms of accomplishing the mission upon which the spacemen and their allies had laboured for half a century, essentially all of the action occurs in the last quarter of this final volume, starting in chapter 44. As usual nothing comes easy, and the project must face a harrowing challenge which might undo everything at the last moment, then confront the cold equations of orbital mechanics. The conclusion is surprising and, while definitively ending this tale, leaves the door open to further adventures set in this universe. This series has been a pure delight from start to finish. It wasn't obvious to this reader at the outset that it would be possible to pull time travel, Vikings, and spaceships together into a story that worked, but the author has managed to do so, while maintaining historical authenticity about a neglected period in European history. It is particularly difficult to craft a time travel yarn in which it is impossible for the characters to change the recorded history of our world, but this is another challenge the author rises to and almost makes it look easy. Independent science fiction is where readers will find the heroes, interesting ideas, and adventure which brought them to science fiction in the first place, and Robert Kroese is establishing himself as a prolific grandmaster of this exciting new golden age. The Kindle edition is free for Kindle Unlimited subscribers.

- In chapter 7, Alma says, “The Titan II rockets used liquid hydrogen for the upper stages, but they used kerosene for the first stage.” This is completely wrong. The Titan II was a two stage rocket and used the same hypergolic propellants (hydrazine fuel and dinitrogen tetroxide oxidiser) in both the first and second stages.

- In chapter 30 it is claimed “While the first stage of a Titan II rocket could be powered by kerosene, the second and third stages needed a fuel with a higher specific impulse in order to reach escape velocity of 25,000 miles per hour.” Oh dear—let's take this point by point. First of all, the first stage of the Titan II was not and could not be powered by kerosene. It was designed for hypergolic fuels, and its turbopumps and lack of an igniter would not work with kerosene. As described below, the earlier Titan I used kerosene, but the Titan II was a major re-design which could not be adapted for kerosene. Second, the second stage of the Titan II used the same hypergolic propellant as the first stage, and this propellant had around the same specific impulse as kerosene and liquid oxygen. Third, the Titan II did not have a third stage at all. It delivered the Gemini spacecraft into orbit using the same two stage configuration as the ballistic missile. The Titan II was later adapted to use a third stage for unmanned space launch missions, but a third stage was never used in Project Gemini. Finally, the mission of the Iron Dragon, like that of the Titan II launching Gemini, was to place its payload in low Earth orbit with a velocity of around 17,500 miles per hour, not escape velocity of 25,000 miles per hour. Escape velocity would fling the payload into orbit around the Sun, not on an intercept course with the target in Earth orbit.

- In chapter 45, it is stated that “Later versions of the Titan II rockets had used hypergolic fuels, simplifying their design.” This is incorrect: the Titan I rocket used liquid oxygen and kerosene (not liquid hydrogen), while the Titan II, a substantially different missile, used hypergolic propellants from inception. Basing the Iron Dragon's design upon the Titan II and then using liquid hydrogen and oxygen makes no sense at all and wouldn't work. Liquid hydrogen is much less dense than the hypergolic fuel used in the Titan II and would require a much larger fuel tank of entirely different design, incorporating insulation which was unnecessary on the Titan II. These changes would ripple all through the design, resulting in an entirely different rocket. In addition, the low density of liquid hydrogen would require an entirely different turbopump design and, not being hypergolic with liquid oxygen, would require a different pre-burner to drive the turbopumps.

- A few sentences later, it is said that “Another difficult but relatively straightforward problem was making the propellant tanks strong enough to be pressurized to 5,000 psi but not so heavy they impeded the rocket's journey to space.” This isn't how tank pressurisation works in liquid fuelled rockets. Tanks are pressurised to increase structural rigidity and provide positive flow into the turbopumps, but pressures are modest. The pressure needed to force propellants into the combustion chamber comes from the boost imparted by the turbopumps, not propellant tank pressurisation. For example, in the Space Shuttle's External Tank, the flight pressure of the liquid hydrogen tank was between 32 and 34 psia, and the liquid oxygen tank 20 to 22 psig, vastly less than “5,000 psi”. A fuel tank capable of withstanding 5,000 psi would be far too heavy to ever get off the ground.

- In chapter 46 we are told, “The Titan II had been adapted from the Atlas intercontinental ballistic missile….” This is completely incorrect. In fact, the Titan I was developed as a backup to the Atlas in case the latter missile's innovative technologies such as the pressure-stabilised “balloon tanks” could not be made to work. The Atlas and Titan I were developed in parallel and, when the Atlas went into service first, the Titan I was quickly retired and replaced by the hypergolic fuelled Titan II, which provided more secure basing and rapid response to a launch order than the Atlas.

- In chapter 50, when the Iron Dragon takes off, those viewing it “squinted against the blinding glare”. But liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen (as well as the hypergolic fuels used by the original Titan II) burn with a nearly invisible flame. Liquid oxygen and kerosene produce a brilliant flame, but these propellants were not used in this rocket.

- And finally, it's not a matter of the text, but what's with that cover illustration, anyway? The rocket ascending in the background is clearly modelled on a Soviet/Russian R-7/Soyuz rocket, which is nothing like what the Iron Dragon is supposed to be. While Iron Dragon is described as a two stage rocket burning liquid hydrogen and oxygen, Soyuz is a LOX/kerosene rocket (and the illustration has the characteristic bright flame of those propellants), has four side boosters (clearly visible), and the spacecraft has a visible launch escape tower, which Gemini did not have and was never mentioned in connection with the Iron Dragon.

Spoilers end here.

Tuesday, June 25, 2019

Gnome-o-gram: Inverted Yield Curve

The yield curve is a measure of the sentiment of investors, particularly conservative investors who own fixed-income securities (bonds and equivalents). (Much of the financial press covers the equity [stock] markets and neglects the bond markets, but the bond markets dwarf the stock market in valuation. Bonds aren't [usually] exciting [and when they are things are generally unpleasant], so they don't get much attention, but if you're interested in the flow of funds [and you should be], that's where you ought to be looking.) The yield curve simply plots, for equivalent fixed-income (debt) securities (bonds), the relationship between the yield of the security and the time to its maturity (when the investor gets his or her money back). For example, consider the most widely traded securities in the world: U.S. Treasury debt. These instruments have various names: Treasury Bills, Treasury Notes, and Treasury Bonds, depending upon their time to maturity, but they all are obligations of the U.S. Treasury and bear the full faith and credit of the United States. They are considered as close to risk-free as any paper investment in the world.

In normal financial circumstances, which is almost all the time, the longer the time to maturity of the investment, the greater the yield. For example, in May 2018, a 90 day U.S. Treasury Bill yielded around 1.6% interest (per annum, as will be all figures quoted). If you were willing to lock in your money for a year, you'd get about 2.25%. Go out five years in a Treasury Note and that would go up to around 2.8%, and with a ten year commitment you'd get 3%. Longer terms would get higher yields, but it's asymptotic—at thirty years in a Treasury Bond you'd only get 3.2%.

Although nothing in investing can be considered normal since 2008, and yield curves in the era of sound money and before artificial repression of interest rates were more linear, the slope of this curve is representative of normal conditions. An investor who locks up their money for a longer term at a fixed rate of return is assuming the risk that they may be repaid in inflated money worth less than that they used to purchase the bond, or that they may forgo more attractive investment opportunities during the time their money is locked up in the bond. (You can always sell a bond before its maturity, but if interest rates have risen since the time you bought it, you'll take a loss compared to what you paid as the purchaser will discount the price so the bond yields a market rate of return.) Therefore, they usually demand a “risk premium” in the form of a higher interest rate on the investment to compensate for these risks. There is always some rate at which investors judge worth tying up their money for a longer time. The greater the perception of risk, the steeper the yield curve. Thus, the yield curve is a sensitive indicator of investors' perception of risks in the future.

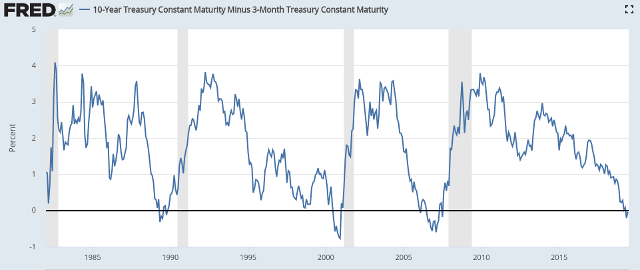

Now let's look at the yield curve, as measured by the spread (difference in yield) between the 10 year U.S. Treasury note and 90 day U.S. Treasury bills, plotted between 1982 and the present, courtesy of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FRED database.

Note how the yield curve, measured by just these two points on the maturity of a single debt security, has varied over the years. At highs, it approaches 4%, while at lows—now that's interesting—it goes negative. What could that signify?

Well, at the simplest level, it means that investors are willing to accept a lower yield for locking their money up for ten years than simply parking it with the Treasury for 90 days. Are they crazy? What are they thinking?

This phenomenon, when the yield curve goes negative, is called an inverted yield curve. There are a number of possible explanations for it, but most of them do not bode well for the economy in the near future. If an investor anticipates an economic slowdown, that slowdown is likely to reduce the demand for capital and will be reflected in lower interest rates. Buying a longer-term bond allows “locking in” today's higher interest rate for the full time until the bond matures, regardless of where interest rates go during that period. If the investor stayed in short-term instruments, they would be rolled over periodically during that time and, if interest rates had fallen, would be renewed at lower yield, resulting in less income compared to the long-term bond. This preference causes investors to bid up the price of longer bonds compared to those with shorter terms, resulting in an inversion of the yield curve. In addition, investors anticipating the sharp drop in equity (stock) markets which often accompanies an economic downturn, may prefer to park their money in a risk-free bond which will provide a guaranteed stable return throughout the anticipated time of turbulence. Thus the yield curve reflects investor sentiment: when it is steeply positive (long rates well above short rates), investors are generally optimistic about the future and demand compensation in the form of higher interest rates for locking their money up and forgoing other opportunities. When they're less sanguine about what's coming, the prospect of not only a guaranteed rate of return on their money but also return of 100% of their money when the bond matures sounds like a pretty good deal compared to the alternatives (such as buying into a historically overpriced stock market late in an economic expansion cycle) and they're willing to accept a lower rate of interest to secure that return. (If you think this paragraph was tangled, check out the work of academic economists on the expectations hypothesis, which says more or less the same thing in intimidating mathematics. There are a number of competing theories to explain the yield curve, and, as usual, economists differ on which best explains the phenomenon.)

Whatever the motivations of investors which result in the rare occurrence of an inverted yield curve, that circumstance has been a reliable indicator of bad times just around the corner. Since 1970, shortly after the dawn of the era of pure paper money and the inflation and exchange rate instability it engendered, there have been eight periods where the yield curve went inverted based upon the monthly rates of 90 day and 10 year U.S. Treasury debt. Seven of these eight periods of yield curve inversion have been followed by economic recessions as declared by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). The time between the onset of the yield curve inversion and the start of the recession has varied between 6 and 17 months, but a recession has always ensued. (Recessions are marked by the grey bars in the yield curve chart above.) Further, there has not been a single recession during that almost half century which was not preceded by an inversion of the yield curve.

“But, you said, ‘Seven out of eight times.’ What about the eighth?”

That's where it gets interesting, and newsworthy. After ten years in positive territory, the yield curve went negative in May, 2019 and has remained negative since then. If a recession does not follow this signal, it will be the first time it has failed to forecast a recession since 1970. An inversion of the yield curve does not forecast the date of onset of the recession or its severity, but history advises that if you're willing to bet a recession (with all of its sequelæ for the stock market, unemployment, budget deficits, and politics) will not start within 18 months or so after the inversion of the yield curve you must really believe that “this time is different”. That, of course, is what all of the sell-side analysts are telling you, but listen to them at your own risk.

My guess, and it's only a guess, is that there may be some financial turbulence ahead, including a media-hyped (but long-overdue) recession in the run-up to the 2018 elections in the U.S. This will, of course, be presented as evidence of the “failure of capitalism” and reason for the electorate to vote for whatever slaver nostrums are on the menu in that contest. There are other indications, still ambivalent, of a gathering storm: gold has just in the last week blown through its five year resistance level at US$1350/troy ounce and raced to more than US$1400, and Bitcoin has exploded to around US$11000/BTC. These are, no doubt, driven in part by fears of the war the Deep State is trying to gin up between the U.S. and Iran in order to take down Trump, but they may also limn the first signs of the inevitable consequences of the market's realisation that there is no consensus in Washington to do anything about the runaway deficits, debt, and inevitable insolvency of the U.S. government and the reserve currency it prints.

What is clear is that inversion of the yield curve is one of the most reliable indicators over the last fifty years that a period of “business as usual” is coming to an end. The indicator has now given its signal. It is prudent to consider the consequences and ponder how prepared you are for what may come next.

Monday, June 24, 2019

Reading List: Billion Dollar Whale

- Wright, Tom and Bradley Hope. Billion Dollar Whale. New York: Hachette Books, 2018. ISBN 978-0-316-43650-2.

- Low Taek Jho, who westernised his name to “Jho Low”, which I will use henceforth, was the son of a wealthy family in Penang, Malaysia. The family's fortune had been founded by Low's grandfather who had immigrated to the then British colony of Malaya from China and founded a garment manufacturing company which Low's father had continued to build and recently sold for a sum of around US$ 15 million. The Low family were among the wealthiest in Malaysia and wanted the best for their son. For the last two years of his high school education, Jho was sent to the Harrow School, a prestigious private British boarding school whose alumni include seven British Prime Ministers including Winston Churchill and Robert Peel, and “foreign students” including Jawaharlal Nehru and King Hussein of Jordan. At Harrow, he would meet classmates whose families' wealth was in the billions, and his ambition to join their ranks was fired. After graduating from Harrow, Low decided the career he wished to pursue would be better served by a U.S. business education than the traditional Cambridge or Oxford path chosen by many Harrovians and enrolled in the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School undergraduate program. Previous Wharton graduates include Warren Buffett, Walter Annenberg, Elon Musk, and Donald Trump. Low majored in finance, but mostly saw Wharton as a way to make connections. Wharton was a school of choice for the sons of Gulf princes and billionaires, and Low leveraged his connections, while still an undergraduate, into meetings in the Gulf with figures such as Yousef Al Otaiba, foreign policy adviser to the sheikhs running the United Arab Emirates. Otaiba, in turn, introduced him to Khaldoon Khalifa Al Mubarak, who ran a fund called Mubadala Development, which was on the cutting edge of the sovereign wealth fund business. Since the 1950s resource-rich countries, in particular the petro-states of the Gulf, had set up sovereign wealth funds to invest the surplus earnings from sales of their oil. The idea was to replace the natural wealth which was being extracted and sold with financial assets that would generate income, appreciate over time, and serve as the basis of their economies when the oil finally ran out. By the early 2000s, the total funds under management by sovereign wealth funds were US$3.5 trillion, comparable to the annual gross domestic product of Germany. Sovereign wealth funds were originally run in a very conservative manner, taking few risks—“gentlemen prefer bonds”—but since the inflation and currency crises of the 1970s had turned to more aggressive strategies to protect their assets from the ravages of Western money printing and financial shenanigans. While some sovereign wealth funds, for example Norway's (with around US$1 trillion in assets the largest in the world) are models of transparency and prudent (albeit often politically correct) investing, others, including some in the Gulf states, are accountable only to autocratic ruler(s) and have been suspected as acting as personal slush funds. On the other hand, managers of Gulf funds must be aware that bad investment decisions may not only cost them their jobs but their heads. Mubadala was a new kind of sovereign wealth fund. Rather than a conservative steward of assets for future generations, it was run more like a leveraged Wall Street hedge fund: borrowing on global markets, investing in complex transactions, and aiming to develop the industries which would sustain the local economy when the oil inevitably ran out. Jho Low saw Al Mubarak, not yet thirty years old, making billion dollar deals on almost his sole discretion, playing a role on the global stage, driving the development of Abu Dhabi's economy, and being handsomely compensated for his efforts. That's the game Low wanted to be in, and he started working toward it. Before graduating from Wharton, he set up a British Virgin Islands company he named the “Wynton Group”, which stood for his goal to “win tons” of money. After graduation in 2005 he began to pitch the contacts he'd made through students at Harrow and Wharton on deals he'd identified in Malaysia, acting as an independent development agency. He put together a series of real estate deals, bringing money from his Gulf contacts and persuading other investors that large sovereign funds were on-board by making token investments from offshore companies he'd created whose names mimicked those of well-known funds. This is a trick he would continue to use in the years to come. Still, he kept his eye on the goal: a sovereign wealth fund, based in Malaysia, that he could use for his own ends. In April 2009 Najib Razak became Malaysia's prime minister. Low had been cultivating a relationship with Najib since he met him through his stepson years before in London. Now it was time to cash in. Najib needed money to shore up his fragile political position and Low was ready to pitch him how to get it. Shortly after taking office, Najib announced the formation of the 1Malaysia Development Berhad, or 1MDB, a sovereign wealth fund aimed at promoting foreign direct investment in projects to develop the economy of Malaysia and benefit all of its ethnic communities: those of Malay, Chinese, and Indian ancestry (hence “1Malaysia”). Although Jho Low had no official position with the fund, he was the one who promoted it, sold Najib on it, and took the lead in raising its capital, both from his contacts in the Gulf and, leveraging that money, in the international debt markets with the assistance of the flexible ethics and unquenchable greed of Goldman Sachs and its ambitious go-getters in Asia. Low's pitch to the prime minister, either explicit or nod-nod, wink-wink, went well beyond high-minded goals such as developing the economy, bringing all ethnic groups together, and creating opportunity. In short, what “corporate social responsibility” really meant was using the fund as Najib's personal piggy bank, funded by naïve foreign investors, to reward his political allies and buy votes, shutting out the opposition. Low told Najib that at the price of aligning his policies with those of his benefactors in the Gulf, he could keep the gravy train running and ensure his tenure in office for the foreseeable future. But what was in it for Low, apart from commissions, finder's fees, and the satisfaction of benefitting his native land? Well, rather more, actually. No sooner did the money hit the accounts of 1MDB than Low set up a series of sham transactions with deceptively-named companies to spirit the money out of the fund and put it into his own pockets. And now it gets a little bit weird for this scribbler. At the centre of all of this skulduggery was a private Swiss bank named BSI. This was my bank. I mean, I didn't own the bank (thank Bob!), but I'd been doing business there (or with its predecessors, before various mergers and acquisitions) since before Jho Low was born. In my dealings with them there were the soul of probity and beyond reproach, but you never know what's going on in the other side of the office, or especially in its branch office in the Wild East of Singapore. Part of the continuo to this financial farce is the battles between BSI's compliance people who kept saying, “Wait, this doesn't make any sense.” and the transaction side people looking at the commissions to be earned for moving the money from who-knows-where to who-knows-whom. But, back to the main story. Ultimately, Low's looting pipeline worked, and he spirited away most of the proceeds of the initial funding of 1MDB into his own accounts or those he controlled. There is a powerful lesson here, as applicable to security of computer systems or access to physical infrastructure as financial assets. Try to chisel a few pennies from your credit card company and you'll be nailed. Fudge a little on your tax return, and it's hard time, serf. But when you play at the billion dollar level, the system was almost completely undefended against an amoral grifter who was bent not on a subtle and creative form of looting in the Bernie Madoff or Enron mold, but simply brazenly picking the pockets of a massive fund through childishly obvious means such as deceptively named offshore shell corporations, shuffling money among accounts in a modern-day version of check kiting, and appealing to banks' hunger for transaction fees over their ethical obligations to their owners and other customers. Nobody knows how much Jho Low looted from 1MBD in this and subsequent transactions. Estimates of the total money spirited out of 1MDB range as high as US$4.5 billion, and Low's profligate spending alone as he was riding high may account for a substantial fraction of that. Much of the book is an account of Low's lifestyle when he was riding high. He was not only utterly amoral when it came to bilking investors, leaving the poor of Malaysia on the hook, but seemingly incapable of looking beyond the next party, gambling spree, or debt repayment. It's like he always thought there'd be a greater fool to fleece, and that there was no degree of wretched excess in his spending which would invite the question “How did he earn this money?” I'm not going to dwell upon this. It's boring. Stylish criminals whose lifestyles are as suave as their crimes are elegant. Grifters who blow money on down-market parties with gutter rappers and supermarket tabloid celebrities aren't. In a marvelous example of meta-irony, Low funded a Hollywood movie production company which made the film The Wolf of Wall Street, about a cynical grifter like Low himself. And now comes the part where I tell you how it all came undone, everybody got their just deserts, and the egregious perpetrators are languishing behind bars. Sorry, not this time, or at least not yet. Jho Low escaped pursuit on his luxury super-yacht and now is reputed to be living in China, travelling freely and living off his ill-gotten gains. The “People's Republic” seems quite hospitable to those who loot the people of its neighbours (assuming they adequately grease the palms of its rulers). Goldman Sachs suffered no sanctions as a result of its complicity in the 1MDB funding and the appropriation of funds. BSI lost its Swiss banking licence, but was acquired by another bank and most of its employees, except for a few involved in dealing with Low, kept their jobs. (My account was transferred to the successor bank with no problems. They never disclosed the reason for the acquisition.) This book, by the two Wall Street Journal reporters who untangled what may be the largest one-man financial heist in human history, provides a look inside the deeply corrupt world of paper money finance at its highest levels, and is an illustration of the extent to which people are disinclined to ask obvious questions like “Where is the money coming from?” while the good times are rolling. What is striking is how banal the whole affair is. Jho Low's talents would have made him a great success in legitimate development finance, but instead he managed to steal billions, ultimately from mostly poor people in his native land, and blow the money on wild parties, shallow celebrities, ostentatious real estate, cars, and yachts, and binges of high-stakes gambling in skeevy casinos. The collapse of the whole tawdry business reflects poorly on institutions like multinational investment banks, large accounting and auditing firms, financial regulators, Swiss banks, and the whole “sustainable development” racket in the third world. Jho Low, a crook through and through, looked at these supposedly august institutions and recognised them as kindred spirits and then figured out transparently simple ways to use them to steal billions. He got away with it, and they are still telling governments, corporations, and investors how to manage their affairs and, inexplicably, being taken seriously and handsomely compensated for their “expertise”.

Monday, June 17, 2019

Reading List: Michoud Assembly Facility

- Manto, Cindy Donze. Michoud Assembly Facility. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2014. ISBN 978-1-5316-6969-0.

- In March, 1763, King Louis XV of France made a land grant of 140 square kilometres to Gilbert Antoine St Maxent, the richest man in Louisiana Territory and commander of the militia. The grant required St Maxent to build a road across the swampy property, develop a plantation, and reserve all the trees in forested areas for the use of the French navy. When the Spanish took over the territory five years later, St Maxent changed his first names to “Gilberto Antonio” and retained title to the sprawling estate. In the decades that followed, the property changed hands and nations several times, eventually, now part of the United States, being purchased by another French immigrant, Antoine Michoud, who had left France after the fall of Napoleon, who his father had served as an official. Michoud rapidly established himself as a prosperous businessman in bustling New Orleans, and after purchasing the large tract of land set about buying pieces which had been sold off by previous owners, re-assembling most of the original French land grant into one of the largest private land holdings in the United States. The property was mostly used as a sugar plantation, although territory and rights were ceded over the years for construction of a lighthouse, railroads, and telegraph and telephone lines. Much of the land remained undeveloped, and like other parts of southern Louisiana was a swamp or, as they now say, “wetlands”. The land remained in the Michoud family until 1910, when it was sold in its entirety for US$410,000 in cash (around US$11 million today) to a developer who promptly defaulted, leading to another series of changes of ownership and dodgy plans for the land, which most people continued to refer to as the Michoud Tract. At the start of World War II, the U.S. government bought a large parcel, initially intended for construction of Liberty ships. Those plans quickly fell through, but eventually a huge plant was erected on the site which, starting in 1943, began to manufacture components for cargo aircraft, lifeboats, and components which were used in the Manhattan Project's isotope separation plants in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. At the end of the war, the plant was declared surplus but, a few years later, with the outbreak of the Korean War, it was re-purposed to manufacture engines for Army tanks. It continued in that role until 1954 when it was placed on standby and, in 1958, once again declared surplus. There things stood until mid-1961 when NASA, charged by the new Kennedy administration to “put a man on the Moon” was faced with the need to build rockets in sizes and quantities never before imagined, and to do so on a tight schedule, racing against the Soviet Union. In June, 1961, Wernher von Braun, director of the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, responsible for designing and building those giant boosters, visited the then-idle Michoud Ordnance Plant and declared it ideal for NASA's requirements. It had 43 acres (17 hectares) under one roof, the air conditioning required for precision work in the Louisiana climate, and was ready to occupy. Most critically, it was located adjacent to navigable waters which would allow the enormous rocket stages, far too big to be shipped by road, rail, or air, to be transported on barges to and from Huntsville for testing and Cape Canaveral in Florida to be launched. In September 1961 NASA officially took over the facility, renaming it “Michoud Operations”, to be managed by NASA Marshall as the manufacturing site for the rockets they designed. Work quickly got underway to set up manufacturing of the first stage of the Saturn I and 1B rockets and prepare to build the much larger first stage of the Saturn V Moon rocket. Before long, new buildings dedicated to assembly and test of the new rockets, occupied both by NASA and its contractors, began to spring up around the original plant. In 1965, the installation was renamed the Michoud Assembly Facility, which name it bears to this day. With the end of the Apollo program, it looked like Michoud might once again be headed for white elephant status, but the design selected for the Space Shuttle included a very large External Tank comparable in size to the first stage of the Saturn V which would be discarded on every flight. Michoud's fabrication and assembly facilities, and its access to shipping by barge were ideal for this component of the Shuttle, and a total of 135 tanks built at Michoud were launched on Shuttle missions between 1981 and 2011. The retirement of the Space Shuttle once again put the future of Michoud in doubt. It was originally tapped to build the core stage of the Constellation program's Ares V booster, which was similar in size and construction to the Shuttle External Tank. The cancellation of Constellation in 2010 brought that to a halt, but then Congress and NASA rode to the rescue with the absurd-as-a-rocket but excellent-as-a-jobs-program Space Launch System (SLS), whose centre core stage also resembles the External Tank and Ares V. SLS first stage fabrication is presently underway at Michoud. Perhaps when the schedule-slipping, bugget-busting SLS is retired after a few flights (if, in fact, it ever flies at all), bringing to a close the era of giant taxpayer-funded throwaway rockets, the Michoud facility can be repurposed to more productive endeavours. This book is largely a history of Michoud in photos and captions, with text introducing chapters on each phase of the facility's history. All of the photos are in black and white, and are well-reproduced. In the Kindle edition many can be expanded to show more detail. There are a number of copy-editing and factual errors in the text and captions, but not too many to distract or mislead the reader. The unidentified “visitors” shown touring the Michoud facility in July 1967 (chapter 3, Kindle location 392) are actually the Apollo 7 crew, Walter Schirra, Donn Eisele, and Walter Cunningham, who would fly on a Michoud-built Saturn 1B in October 1968. For a book of just 130 pages, most of which are black and white photographs, the hardcover is hideously expensive (US$29 at this writing). The Kindle edition is still pricey (US$13 list price), but may be read for free by Kindle Unlimited subscribers.

Friday, June 14, 2019

Reading List: Five Million Watts

- Wood, Fenton. Five Million Watts. Seattle: Amazon Digital Services, 2019. ASIN B07R6X973N.

- This is the second short novel/novella (123 pages) in the author's Yankee Republic series. I described the first, Pirates of the Electromagnetic Waves (May 2019), as “utterly charming”, and this sequel turns it all the way up to “enchanting”. As with the first book, you're reading along thinking this is a somewhat nerdy young adult story, then something happens or is mentioned in passing and suddenly, “Whoa—I didn't see that coming!”, and you realise the Yankee Republic is a strange and enchanted place, and that, as in the work of Philip K. Dick, there is a lot more going on than you suspected, and much more to be discovered in future adventures. This tale begins several years after the events of the first book. Philo Hergenschmidt (the only character from Pirates to appear here) has grown up, graduated from Virginia Tech, and after a series of jobs keeping antiquated equipment at rural radio stations on the air, arrives in the Republic's storied metropolis of Iburakon to seek opportunity, adventure, and who knows what else. (If you're curious where the name of the city came from, here's a hint, but be aware it may be a minor spoiler.) Things get weird from the very start when he stops at an information kiosk and encounters a disembodied mechanical head who says it has a message for him. The message is just an address, and when he goes there he meets a very curious character who goes by a variety of names ranging from Viridios to Mr Green, surrounded by a collection of keyboard instruments including electronic synthesisers with strange designs. Viridios suggests Philo aim for the very top and seek employment at legendary AM station 2XG, a broadcasting pioneer that went on the air in 1921, before broadcasting was regulated, and which in 1936 increased its power to five million watts. When other stations' maximum power was restricted to 50,000 watts, 2XG was grandfathered and allowed to continue to operate at 100 times more, enough to cover the continent far beyond the borders of the Yankee Republic into the mysterious lands of the West. Not only does 2XG broadcast with enormous power, it was also permitted to retain its original 15 kHz bandwidth, allowing high-fidelity broadcasting and even, since the 1950s, stereo (for compatible receivers). However, in order to retain its rights to the frequency and power, the station was required to stay on the air continuously, with any outage longer than 24 hours forfeiting its rights to hungry competitors. The engineers who maintained this unique equipment were a breed apart, the pinnacle of broadcast engineering. Philo manages to secure a job as a junior technician, which means he'll never get near the high power RF gear or antenna (all of which are one-off custom), but sets to work on routine maintenance of studio gear and patching up ancient tube gear when it breaks down. Meanwhile, he continues to visit Viridios and imbibe his tales of 2XG and the legendary Zaros the Electromage who designed its transmitter, the operation of which nobody completely understands today. As he hears tales of the Old Religion, the gods of the spring and grain, and the time of the last ice age, Philo concludes Viridios is either the most magnificent liar he has ever encountered or—something else again. Climate change is inexorably closing in on Iburakon. Each year is colder than the last, the growing season is shrinking, and it seems inevitable that before long the glaciers will resume their march from the north. Viridios is convinced that the only hope lies in music, performing a work rooted in that (very) Old Time Religion which caused a riot in its only public performance decades before, broadcast with the power of 2XG and performed with breakthrough electronic music instruments of his own devising. Viridios is very odd, but also persuasive, and he has a history with 2XG. The concert is scheduled, and Philo sets to work restoring long-forgotten equipment from the station's basement and building new instruments to Viridios' specifications. It is a race against time, as the worst winter storm in memory threatens 2XG and forces Philo to confront one of his deepest fears. Working on a project on the side, Philo discovers what may be the salvation of 2XG, but also as he looks deeper, possibly the door to a new universe. Once again, we have a satisfying, heroic, and imaginative story, suitable for readers of all ages, that leaves you hungry for more. At present, only a Kindle edition is available. The book is not available under the Kindle Unlimited free rental programme, but is inexpensive to buy. Those eagerly awaiting the next opportunity to visit the Yankee Republic will look forward to the publication of volume 3, The Tower of the Bear, in October, 2019.

Monday, June 10, 2019

Reading List: The Case for Trump

- Hanson, Victor Davis. The Case for Trump. New York: Basic Books, 2019. ISBN 978-1-5416-7354-0.

- The election of Donald Trump as U.S. president in November 2016 was a singular event in the history of the country. Never before had anybody been elected to that office without any prior experience in either public office or the military. Trump, although running as a Republican, had no long-term affiliation with the party and had cultivated no support within its establishment, elected officials, or the traditional donors who support its candidates. He turned his back on the insider consultants and “experts” who had advised GOP candidate after candidate in their “defeat with dignity” at the hands of a ruthless Democrat party willing to burn any bridge to win. From well before he declared his candidacy he established a direct channel to a mass audience, bypassing media gatekeepers via Twitter and frequent appearances in all forms of media, who found him a reliable boost to their audience and clicks. He was willing to jettison the mumbling points of the cultured Beltway club and grab “third rail” issues of which they dared not speak such as mass immigration, predatory trade practices, futile foreign wars, and the exporting of jobs from the U.S. heartland to low-wage sweatshops overseas. He entered a free-for-all primary campaign as one of seventeen major candidates, including present and former governors, senators, and other well-spoken and distinguished rivals and, one by one, knocked them out, despite resolute and sometimes dishonest bias by the media hosting debates, often through “verbal kill shots” which made his opponents the target of mockery and pinned sobriquets on them (“low energy Jeb”, “little Marco”, “lyin' Ted”) they couldn't shake. His campaign organisation, if one can dignify it with the term, was completely chaotic and his fund raising nothing like the finely-honed machines of establishment favourites like Jeb Bush, and yet his antics resulted in his getting billions of dollars worth of free media coverage even on outlets who detested and mocked him. One by one, he picked off his primary opponents and handily won the Republican presidential nomination. This unleashed a phenomenon the likes of which had not been seen since the Goldwater insurgency of 1964, but far more virulent. Pillars of the Republican establishment and Conservatism, Inc. were on the verge of cardiac arrest, advancing fantasy scenarios to deny the nomination to its winner, publishing issues of their money-losing and subscription-shedding little magazines dedicated to opposing the choice of the party's voters, and promoting insurgencies such as the candidacy of Egg McMuffin, whose bona fides as a man of the people were evidenced by his earlier stints with the CIA and Goldman Sachs. Predictions that post-nomination, Trump would become “more presidential” were quickly falsified as the chaos compounded, the tweets came faster and funnier, and the mass rallies became ever more frequent and raucous. One thing that was obvious to anybody looking dispassionately at what was going on, without the boiling blood of hatred and disdain of the New York-Washington establishment, was that the candidate was having the time of his life and so were the people who attended the rallies. But still, all of the wise men of the coastal corridor knew what must happen. On the eve of the general election, polls put the probability of a Trump victory somewhere between 1 and 15 percent. The outlier was Nate Silver, who went out on a limb and went all the way up to 29% chance of Trump's winning to the scorn of his fellow “progressives” and pollsters. And yet, Trump won, and handily. Yes, he lost the popular vote, but that was simply due to the urban coastal vote for which he could not contend and wisely made no attempt to attract, knowing such an effort would be futile and a waste of his scarce resources (estimates are his campaign spent around half that of Clinton's). This book by classicist, military historian, professor, and fifth-generation California farmer Victor Davis Hanson is an in-depth examination of, in the words of the defeated candidate, “what happened”. There is a great deal of wisdom here. First of all, a warning to the prospective reader. If you read Dr Hanson's columns regularly, you probably won't find a lot here that's new. This book is not one of those that's obviously Frankenstitched together from previously published columns, but in assembling their content into chapters focussing on various themes, there's been a lot of cut and paste, if not literally at the level of words, at least in terms of ideas. There is value in seeing it all presented in one package, but be prepared to say, from time to time, “Haven't I've read this before?” That caveat lector aside, this is a brilliant analysis of the Trump phenomenon. Hanson argues persuasively that it is very unlikely any of the other Republican contenders for the nomination could have won the general election. None of them were talking about the issues which resonated with the erstwhile “Reagan Democrat” voters who put Trump over the top in the so-called “blue wall” states, and it is doubtful any of them would have ignored their Beltway consultants and campaigned vigorously in states such as Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania which were key to Trump's victory. Given that the Republican defeat which would likely have been the result of a Bush (again?), Rubio, or Cruz candidacy would have put the Clinton crime family back in power and likely tipped the Supreme Court toward the slaver agenda for a generation, that alone should give pause to “never Trump” Republicans. How will it all end? Nobody knows, but Hanson provides a variety of perspectives drawn from everything from the Byzantine emperor Justinian's battle against the deep state to the archetype of the rough-edged outsider brought in to do what the more civilised can't or won't—the tragic hero from Greek drama to Hollywood westerns. What is certain is that none of what Trump is attempting, whether it ends in success or failure, would be happening if any of his primary opponents or the Democrat in the general election had prevailed. I believe that Victor Davis Hanson is one of those rare people who have what I call the “Orwell gift”. Like George Orwell, he has the ability to look at the facts, evaluate them, and draw conclusions without any preconceived notions or filtering through an ideology. What is certain is that with the election of Donald Trump in 2016 the U.S. dodged a bullet. Whether that election will be seen as a turning point which reversed the decades-long slide toward tyranny by the administrative state, destruction of the middle class, replacement of the electorate by imported voters dependent upon the state, erosion of political and economic sovereignty in favour of undemocratic global governance, and the eventual financial and moral bankruptcy which are the inevitable result of all of these, or just a pause before the deluge, is yet to be seen. Hanson's book is an excellent, dispassionate, well-reasoned, and thoroughly documented view of where things stand today.

Wednesday, June 5, 2019

Reading List: Planetary: Earth

- Witzke, Dawn, ed. Planetary: Earth. Narara, NSW, Australia: Superversive Press, 2018. ISBN 978-1-925645-24-8.

- This is the fourth book in the publisher's Planetary Anthology series. Each volume contain stories set on, or figuring in the plot, the named planet. Previous collections have featured Mercury, Venus, and Mars. This installment contains stories related in some way to Earth, although in several none of the action occurs on that planet. Back the day (1930s through 1980s) monthly science fiction magazines were a major venue for the genre and the primary path for aspiring authors to break into print. Sold on newsstands for the price of a few comic books, they were the way generations of young readers (including this one) discovered the limitless universe of science fiction. A typical issue might contain five or six short stories, a longer piece (novella or novelette), and a multi-month serialisation of a novel, usually by an established author known to the readers. For example, Frank Herbert's Dune was serialised in two long runs in Analog in 1963 and 1965 before its hardcover publication in 1965. In addition, there were often book reviews, a column about science fact (Fantasy and Science Fiction published a monthly science column by Isaac Asimov which ran from 1958 until shortly before his death in 1992—a total of 399 in all), a lively letters to the editor section, and an editorial. All of the major science fiction monthlies welcomed unsolicited manuscripts from unpublished authors, and each issue was likely to contain one or two stories from the “slush pile” which the editor decided made the cut for the magazine. Most of the outstanding authors of the era broke into the field this way, and some editors such as John W. Campbell of Astounding (later Analog) invested much time and effort in mentoring promising talents and developing them into a reliable stable of writers to fill the pages of their magazines. By the 1990s, monthly science fiction magazines were in decline, and the explosion of science fiction novel publication had reduced the market for short fiction. By the year 2000, only three remained in the U.S., and their circulations continued to erode. Various attempts to revive a medium for short fiction have been tried, including Web magazines. This collection is an example of another genre: the original anthology. While most anthologies published in book form in the heyday of the magazines had previously been published in the magazines (authors usually only sold the magazine “first North American serial rights” and retained the right to subsequently sell the story to the publisher of an anthology), original anthologies contain never-before-published stories, usually collected around a theme such as the planet Earth here. I got this book (I say “got” as opposed to “bought” because the Kindle edition is free to Kindle Unlimited subscribers and I “borrowed” it as one of the ten titles I can check out for reading at a given time) because it contained the short story, “The Hidden Conquest”, by Hans G. Schantz, author of the superb Hidden Truth series of novels (1, 2, 3), which was said to be a revealing prequel to the story in the books. It is, and it is excellent, although you probably won't appreciate how much of a reveal it is unless you've read the books, especially 2018's The Brave and the Bold. The rest of the stories are…uneven: about what you'd expect from a science fiction magazine in the 1950s or '60s. Some are gimmick stories, others are shoot-em-up action tales, while still others are just disappointing and probably should have remained in the slush pile or returned to their authors with a note attached to the rejection slip offering a few suggestions and encouragement to try again. Copy editing is sloppy, complete with a sprinkling of idiot “its/it's” plus the obligatory “pulled hard on the reigns” “miniscule”, and take your “breathe” away. But hey, if you got it from Kindle Unlimited, you can hardly say you didn't get your money's worth, and you're perfectly free to borrow it, read the Hans Schantz story, and return it same day. I would not pay the US$4 to buy the Kindle edition outright, and fifteen bucks for a paperback is right out.

Reading List: The Case for Space

- Zubrin, Robert. The Case for Space. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2019. ISBN 978-1-63388-534-9.

- Fifty years ago, with the successful landing of Apollo 11 on the Moon, it appeared that the road to the expansion of human activity from its cradle on Earth into the immensely larger arena of the solar system was open. The infrastructure built for Project Apollo, including that in the original 1963 development plan for the Merritt Island area could support Saturn V launches every two weeks. Equipped with nuclear-powered upper stages (under active development by Project NERVA, and accommodated in plans for a Nuclear Assembly Building near the Vehicle Assembly Building), the launchers and support facilities were more than adequate to support construction of a large space station in Earth orbit, a permanently-occupied base on the Moon, exploration of near-Earth asteroids, and manned landings on Mars in the 1980s. But this was not to be. Those envisioning this optimistic future fundamentally misunderstood the motivation for Project Apollo. It was not about, and never was about, opening the space frontier. Instead, it was a battle for prestige in the Cold War and, once won (indeed, well before the Moon landing), the budget necessary to support such an extravagant program (which threw away skyscraper-sized rockets with every launch), began to evaporate. NASA was ready to do the Buck Rogers stuff, but Washington wasn't about to come up with the bucks to pay for it. In 1965 and 1966, the NASA budget peaked at over 4% of all federal government spending. By calendar year 1969, when Apollo 11 landed on the Moon, it had already fallen to 2.31% of the federal budget, and with relatively small year to year variations, has settled at around one half of one percent of the federal budget in recent years. Apart from a small band of space enthusiasts, there is no public clamour for increasing NASA's budget (which is consistently over-estimated by the public as a much larger fraction of federal spending than it actually receives), and there is no prospect for a political consensus emerging to fund an increase. Further, there is no evidence that dramatically increasing NASA's budget would actually accomplish anything toward the goal of expanding the human presence in space. While NASA has accomplished great things in its robotic exploration of the solar system and building space-based astronomical observatories, its human space flight operations have been sclerotic, risk-averse, loath to embrace new technologies, and seemingly more oriented toward spending vast sums of money in the districts and states of powerful representatives and senators than actually flying missions. Fortunately, NASA is no longer the only game in town (if it can even be considered to still be in the human spaceflight game, having been unable to launch its own astronauts into space without buying seats from Russia since the retirement of the Space Shuttle in 2011). In 2009, the commission headed by Norman Augustine recommended cancellation of NASA's Constellation Program, which aimed at a crewed Moon landing in 2020, because they estimated that the heavy-lift booster it envisioned (although based largely on decades-old Space Shuttle technology) would take twelve years and US$36 billion to develop under NASA's business-as-usual policies; Constellation was cancelled in 2010 (although its heavy-lift booster, renamed. de-scoped, re-scoped, schedule-slipped, and cost-overrun, stumbles along, zombie-like, in the guise of the Space Launch System [SLS] which has, to date, consumed around US$14 billion in development costs without producing a single flight-ready rocket, and will probably cost between one and two billion dollars for each flight, every year or two—this farce will probably continue as long as Richard Shelby, the Alabama Senator who seems to believe NASA stands for “North Alabama Spending Agency”, remains in the World's Greatest Deliberative Body). In February 2018, SpaceX launched its Falcon Heavy booster, which has a payload capacity to low Earth orbit comparable to the initial version of the SLS, and was developed with private funds in half the time at one thirtieth the cost (so far) of NASA's Big Rocket to Nowhere. Further, unlike the SLS, which on each flight will consign Space Shuttle Main Engines and Solid Rocket Boosters (which were designed to be reusable and re-flown many times on the Space Shuttle) to a watery grave in the Atlantic, three of the four components of the Falcon Heavy (excluding only its upper stage, with a single engine) are reusable and can be re-flown as many as ten times. Falcon Heavy customers will pay around US$90 million for a launch on the reusable version of the rocket, less than a tenth of what NASA estimates for an SLS flight, even after writing off its enormous development costs. On the heels of SpaceX, Jeff Bezos's Blue Origin is developing its New Glenn orbital launcher, which will have comparable payload capacity and a fully reusable first stage. With competition on the horizon, SpaceX is developing the Super Heavy/Starship completely-reusable launcher with a payload of around 150 tonnes to low Earth orbit: more than any past or present rocket. A fully-reusable launcher with this capacity would also be capable of delivering cargo or passengers between any two points on Earth in less than an hour at a price to passengers no more than a first class ticket on a present-day subsonic airliner. The emergence of such a market could increase the demand for rocket flights from its current hundred or so per year to hundreds or thousands a day, like airline operations, with consequent price reductions due to economies of scale and moving all components of the transportation system down the technological learning curve. Competition-driven decreases in launch cost, compounded by partially- or fully-reusable launchers, is already dramatically decreasing the cost of getting to space. A common metric of launch cost is the price to launch one kilogram into low Earth orbit. This remained stubbornly close to US$10,000/kg from the 1960s until the entry of SpaceX's Falcon 9 into the market in 2010. Purely by the more efficient design and operations of a profit-driven private firm as opposed to a cost-plus government contractor, the first version of the Falcon 9 cut launch costs to around US$6,000/kg. By reusing the first stage of the Falcon 9 (which costs around three times as much as the expendable second stage), this was cut by another factor of two, to US$3,000/kg. The much larger fully reusable Super Heavy/Starship is projected to reduce launch cost (if its entire payload capacity can be used on every flight, which probably isn't the way to bet) to the vicinity of US$250/kg, and if the craft can be flown frequently, say once a day, as somebody or other envisioned more than a quarter century ago, amortising fixed costs over a much larger number of launches could reduce cost per kilogram by another factor of ten, to something like US$25/kg. Such cost reductions are an epochal change in the space business. Ever since the first Earth satellites, launch costs have dominated the industry and driven all other aspects of spacecraft design. If you're paying US$10,000 per kilogram to put your satellite in orbit, it makes sense to spend large sums of money not only on reducing its mass, but also making it extremely reliable, since launching a replacement would be so hideously expensive (and with flight rates so low, could result in a delay of a year or more before a launch opportunity became available). But with a hundred-fold or more reduction in launch cost and flights to orbit operating weekly or daily, satellites need no longer be built like precision watches, but rather industrial gear like that installed in telecom facilities on the ground. The entire cost structure is slashed across the board, and space becomes an arena accessible for a wide variety of commercial and industrial activities where its unique characteristics, such as access to free, uninterrupted solar power, high vacuum, and weightlessness are an advantage. But if humanity is truly to expand beyond the Earth, launching satellites that go around and around the Earth providing services to those on its surface is just the start. People must begin to homestead in space: first hundreds, then thousands, and eventually millions and more living, working, building, raising families, with no more connection to the Earth than immigrants to the New World in the 1800s had to the old country in Europe or Asia. Where will they be living, and what will they be doing? In order to think about the human future in the solar system, the first thing you need to do is recalibrate how you think about the Earth and its neighbours orbiting the Sun. Many people think of space as something like Antarctica: barren, difficult and expensive to reach, unforgiving, and while useful for some forms of scientific research, no place you'd want to set up industry or build communities where humans would spend their entire lives. But space is nothing like that. Ninety-nine percent or more of the matter and energy resources of the solar system—the raw material for human prosperity—are found not on the Earth, but rather elsewhere in the solar system, and they are free for the taking by whoever gets there first and figures out how to exploit them. Energy costs are a major input to most economic activity on the Earth, and wars are regularly fought over access to scarce energy resources on the home planet. But in space, at the distance Earth orbits the Sun, 1.36 kilowatts of free solar power are available for every square metre of collector you set up. And, unlike on the Earth's surface, that power is available 24 hours a day, every day of the year, and will continue to flow for billions of years into the future. Settling space will require using the resources available in space, not just energy but material. Trying to make a space-based economy work by launching everything from Earth is futile and foredoomed. Regardless of how much you reduce launch costs (even with exotic technologies which may not even be possible given the properties of materials, such as space elevators or launch loops), the vast majority of the mass needed by a space-based civilisation will be dumb bulk materials, not high-tech products such as microchips. Water; hydrogen and oxygen for rocket fuel (which are easily made from water using electricity from solar power); aluminium, titanium, and steel for structural components; glass and silicon; rocks and minerals for agriculture and bulk mass for radiation shielding; these will account for the overwhelming majority of the mass of any settlement in space, whether in Earth orbit, on the Moon or Mars, asteroid mining camps, or habitats in orbit around the Sun. People and low-mass, high-value added material such as electronics, scientific instruments, and the like will launch from the Earth, but their destinations will be built in space from materials found there. Why? As with most things in space, it comes down to delta-v (pronounced delta-vee), the change in velocity needed to get from one location to another. This, not distance, determines the cost of transportation in space. The Earth's mass creates a deep gravity well which requires around 9.8 km/sec of delta-v to get from the surface to low Earth orbit. It is providing this boost which makes launching payloads from the Earth so expensive. If you want to get to geostationary Earth orbit, where most communication satellites operate, you need another 3.8 km/sec, for a total of 13.6 km/sec launching from the Earth. By comparison, delivering a payload from the surface of the Moon to geostationary Earth orbit requires only 4 km/sec, which can be provided by a simple single-stage rocket. Delivering material from lunar orbit (placed there, for example, by a solar powered electromagnetic mass driver on the lunar surface) to geostationary orbit needs just 2.4 km/sec. Given that just about all of the materials from which geostationary satellites are built are available on the Moon (if you exploit free solar power to extract and refine them), it's clear a mature spacefaring economy will not be launching them from the Earth, and will create large numbers of jobs on the Moon, in lunar orbit, and in ferrying cargos among various destinations in Earth-Moon space. The author surveys the resources available on the Moon, Mars, near-Earth and main belt asteroids, and, looking farther into the future, the outer solar system where, once humans have mastered controlled nuclear fusion, sufficient Helium-3 is available for the taking to power a solar system wide human civilisation of trillions of people for billions of years and, eventually, the interstellar ships they will use to expand out into the galaxy. Detailed plans are presented for near-term human missions to the Moon and Mars, both achievable within the decade of the 2020s, which will begin the process of surveying the resources available there and building the infrastructure for permanent settlement. These mission plans, unlike those of NASA, do not rely on paper rockets which have yet to fly, costly expendable boosters, or detours to “gateways” and other diversions which seem a prime example of (to paraphrase the author in chapter 14), “doing things in order to spend money as opposed to spending money in order to do things.” This is an optimistic and hopeful view of the future, one in which the human adventure which began when our ancestors left Africa to explore and settle the far reaches of their home planet continues outward into its neighbourhood around the Sun and eventually to the stars. In contrast to the grim Malthusian vision of mountebanks selling nostrums like a “Green New Deal”, which would have humans huddled on an increasingly crowded planet, shivering in the cold and dark when the Sun and wind did not cooperate, docile and bowed to their enlightened betters who instruct them how to reduce their expectations and hopes for the future again and again as they wait for the asteroid impact to put an end to their misery, Zubrin sketches millions of diverse human (and eventually post-human, evolving in different directions) societies, exploring and filling niches on a grand scale that dwarfs that of the Earth, inventing, building, experimenting, stumbling, and then creating ever greater things just as humans have for millennia. This is a future not just worth dreaming of, but working to make a reality. We have the enormous privilege of living in the time when, with imagination, courage, the willingness to take risks and to discard the poisonous doctrines of those who preach “sustainability” but whose policies always end in resource wars and genocide, we can actually make it happen and see the first steps taken in our lifetimes. Here is an interview with the author about the topics discussed in the book. This is a one hour and forty-two minute interview (audio only) from “The Space Show” which goes into the book in detail.