« November 2018 | Main | January 2019 »

Monday, December 31, 2018

Books of the Year: 2018

Here are my picks for the best books of 2018, fiction and nonfiction. These aren't the best books published this year, but rather the best I've read in the last twelve months. The winner in both categories is barely distinguished from the pack, and the runners up are all worthy of reading. Runners up appear in alphabetical order by their author's surname. Each title is linked to my review of the book.Fiction:

Winner:Runners up:

- A Rambling Wreck and The Brave and the Bold by Hans G. Schantz

I am jointly choosing these two novels as fiction books of the year. They are part of the ongoing Hidden Truth saga, the first volume of which was a 2017 Book of the Year.

- The Narrative by Deplora Boule [pseud.]

- The Red Cliffs of Zerhoun by Matthew Bracken

- The Dream of the Iron Dragon by Robert Kroese

- Sanity by Neovictorian [pseud.] and Neal Van Wahr

Nonfiction:

Winner:Runners up:

- Life 3.0 by Max Tegmark

- Bad Blood by John Carreyrou

- Life After Google by George Gilder

- The Second World Wars by Victor Davis Hanson

- Antifragile by Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Wednesday, December 26, 2018

Reading List: Iron Sunrise

- Stross, Charles. Iron Sunrise. New York: Ace, 2005. ISBN 978-0-441-01296-1.

-

In Accelerando (July 2011), a

novel assembled from nine previously-published short stories,

the author chronicles the arrival of a technological singularity

on Earth: the almost-instantaneously emerging super-intellect

called the Eschaton which departed the planet toward the stars.

Simultaneously, nine-tenths of Earth's population vanished

overnight, and those left behind, after a period of chaos, found

that with the end of scarcity brought about by “cornucopia

machines” produced in the first phase of the singularity,

they could dispense with anachronisms such as economic systems

and government. After humans achieved faster than light travel,

they began to discover that the Eschaton had relocated 90% of

Earth's population to habitable worlds around various stars and

left them to develop in their own independent directions, guided

only by this message from the Eschaton, inscribed on a monument

on each world.

The wormholes used by the Eschaton to relocate Earth's population in the great Diaspora, a technology which humans had yet to understand, not only permitted instantaneous travel across interstellar distances but also in time: the more distant the planet from Earth, the longer the settlers deposited there have had to develop their own cultures and civilisations before being contacted by faster than light ships. With cornucopia machines to meet their material needs and allow them to bootstrap their technology, those that descended into barbarism or incessant warfare did so mostly due to bad ideas rather than their environment. Rachel Mansour, secret agent for the Earth-based United Nations, operating under the cover of an entertainment officer (or, if you like, cultural attaché), who we met in the previous novel in the series, Singularity Sky (February 2011), and her companion Martin Springfield, who has a back-channel to the Eschaton, serve as arms control inspectors—their primary mission to insure that nothing anybody on Earth or the worlds who have purchased technology from Earth invites the wrath of the Eschaton—remember that “Or else.” A terrible fate has befallen the planet Moscow, a diaspora “McWorld” accomplished in technological development and trade, when its star, a G-type main sequence star like the Sun, explodes in a blast releasing a hundredth the energy of a supernova, destroying all life on planet Moscow within an instant of the wavefront reaching it, and the entire planet within an hour. The problem is, type G stars just don't explode on their own. Somebody did this, quite likely using technologies which risk Big E's “or else” on whoever was responsible (or it concluded was responsible). What's more, Moscow maintained a slower-than-light deterrent fleet with relativistic planet-buster weapons to avenge any attack on their home planet. This fleet, essentially undetectable en route, has launched against New Dresden, a planet with which Moscow had a nonviolent trade dispute. The deterrent fleet can be recalled only by coded messages from two Moscow system ambassadors who survived the attack at their postings in other systems, but can also be sent an irrevocable coercion code, which cancels the recall and causes any further messages to be ignored, by three ambassadors. And somebody seems to be killing off the remaining Moscow ambassadors: if the number falls below two, the attack will arrive at New Dresden in thirty-five years and wipe out the planet and as many of its eight hundred million inhabitants as have not been evacuated. Victoria Strowger, who detests her name and goes by “Wednesday”, has had an invisible friend since childhood, “Herman”, who speaks to her through her implants. As she's grown up, she has come to understand that, in some way, Herman is connected to Big E and, in return for advice and assistance she values highly, occasionally asks her for favours. Wednesday and her family were evacuated from one of Moscow's space stations just before the deadly wavefront from the exploded star arrived, with Wednesday running a harrowing last “errand” for Herman before leaving. Later, in her new home in an asteroid in the Septagon system, she becomes the target of an attack seemingly linked to that mystery mission, and escapes only to find her family wiped out by the attackers. With Herman's help, she flees on an interstellar liner. While Singularity Sky was a delightful romp describing a society which had deliberately relinquished technology in order to maintain a stratified class system with the subjugated masses frozen around the Victorian era, suddenly confronted with the merry pranksters of the Festival, who inject singularity-epoch technology into its stagnant culture, Iron Sunrise is a much more conventional mystery/adventure tale about gaining control of the ambassadorial keys, figuring out who are the good and bad guys, and trying to avert a delayed but inexorably approaching genocide. This just didn't work for me. I never got engaged in the story, didn't find the characters particularly interesting, nor came across any interesting ways in which the singularity came into play (and this is supposed to be the author's “Singularity Series”). There are some intriguing concepts, for example the “causal channel”, in which quantum-entangled particles permit instantaneous communication across spacelike separations as long as the previously-prepared entangled particles have first been delivered to the communicating parties by slower than light travel. This is used in the plot to break faster than light communication where it would be inconvenient for the story line (much as all those circumstances in Star Trek where the transporter doesn't work for one reason or another when you're tempted to say “Why don't they just beam up?”). The apparent villains, the ReMastered, (think Space Nazis who believe in a Tipler-like cult of Omega Point out-Eschaton-ing the Eschaton, with icky brain-sucking technology) were just over the top. Accelerando and Singularity Sky were thought-provoking and great fun. This one doesn't come up to that standard.- I am the Eschaton. I am not your god.

- I am descended from you, and I exist in your future.

- Thou shalt not violate causality within my historic light cone. Or else.

Tuesday, December 25, 2018

Gnome-o-gram: Whence Gold?

By the time I was in

high school in the 1960s, the origin of the chemical elements seemed

pretty clear. Hydrogen was created in the Big Bang, and very shortly

afterward about one quarter of it fused to make helium with a little

bit of lithium. (This process is now called Big Bang

nucleosynthesis, and models of it agree very well with astronomical

observations of primordial gases in the universe.)

By the time I was in

high school in the 1960s, the origin of the chemical elements seemed

pretty clear. Hydrogen was created in the Big Bang, and very shortly

afterward about one quarter of it fused to make helium with a little

bit of lithium. (This process is now called Big Bang

nucleosynthesis, and models of it agree very well with astronomical

observations of primordial gases in the universe.)

All of the heavier elements, including the carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen which, along with hydrogen, make up our bodies and all other living things on Earth, were made in stars which fused hydrogen into these heavier elements. Eventually, the massive stars fused lighter elements into iron, which cannot be fused further, and collapsed, resulting in a supernova explosion which spewed these heavy elements into space, where they were incorporated into later generations of stars such as the Sun and eventually found their way into planets and you and me. We are stardust. But we are made of these lighter elements—we are not golden.

But, as more detailed investigations into the life and death of stars proceeded, something didn't add up. Yes, you can make all of the elements up to iron in massive stars, and the abundances found in the universe agree pretty well with the models of the life and death of these stars, but the heavier elements such as gold, lead, and uranium just didn't compute: they have a large fraction of neutrons in their nuclei (if they didn't, they'd be radioactive [or more radioactive than they already are] and would have decayed long before we came on the scene to observe them), and the process of a supernova explosion doesn't seem to have any way to create nuclei with so many neutrons. "Then, a miracle happens" worked in the early days of astrophysics, but once people began to really crunch the numbers, it didn't cut it any more.

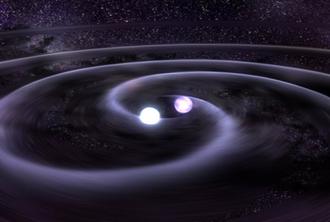

Where could all of those neutrons could have come from, and what

could have provided the energy to create these heavy and relatively

rare nuclei? Well, if you're looking for lots of neutrons all in the

same place at the same time, there's no better place than a neutron star,

which is a tiny object (radius around 10 km) with a mass greater than

that of the Sun, which is entirely made of them. And if it's energy

you're needing, well how about smashing two of them together at a

velocity comparable to the speed of light? (Or, more precisely, the

endpoint of the in-spiral of two neutron stars in a close orbit as

their orbital energy decays due to emission of gravitational

radiation.) Something like this, say.

This was all theory until 12:41 UTC on 2017-08-17, when gravitational wave detectors triggered on an event which turned out to be, after detailed analysis, the strongest gravitational wave ever detected. Because it was simultaneously observed by detectors in the U.S. in Washington state and Louisiana and in Italy, it was possible to localise the region in the sky from which it originated. At almost the same time, NASA and European Space Agency satellites in orbit detected a weak gamma ray burst. Before the day was out, ground-based astronomers found an anomalous source in the relatively nearby (130 million light years away) galaxy NGC 4993, which was subsequently confirmed by instruments on the ground and in space across a wide swath of the electromagnetic spectrum. This was an historic milestone in multi-messenger astronomy: for the first time an event had been observed both by gravitational and electromagnetic radiation: two entirely different channels by which we perceive the universe.

These observations allowed determining the details of the material ejected from the collision. Most of the mass of the two neutron stars went to form a black hole, but a fraction was ejected in a neutron- and energy-rich soup from which stable heavy elements could form. The observations closely agreed with the calculations of theorists who argued that elements heavier than iron that we observe in the universe are mostly formed in collisions of neutron stars.

Think about it. Do you have bit of gold on your finger, or around your neck, or hanging from your ears? Where did it come from? Well, probably it was dug up from beneath the Earth, but before that? To make it, first two massive stars had to form in the early universe, live their profligate lives, then explode in cataclysmic supernova explosions. Then the remnants of these explosions, neutron stars, had to find themselves in a death spiral as the inexorable dissipation of gravitational radiation locked them into a deadly embrace. Finally, they collided, releasing enough energy to light up the universe and jiggle our gravitational wave detectors 130 million years after the event. And then they spewed whole planetary masses of gold, silver, platinum, lead, uranium, and heaven knows how many other elements the news of which has yet to come to Harvard into the interstellar void.

In another document, I have discussed how relativity explains why gold has that mellow glow. Now we observed where gold ultimately comes from. And once again, you can't explain it without (in this case, general) relativity.

In a way, we've got ourselves back to the garden.

Monday, December 24, 2018

Reading List: Days of Rage

- Burrough, Bryan. Days of Rage. New York: Penguin Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0-14-310797-2.

-

In the year 1972, there were more than 1900 domestic bombings in

the United States. Think about that—that's more than

five bombings a day. In an era when the occasional

terrorist act by a “lone wolf” nutcase gets round

the clock coverage on cable news channels, it's hard to imagine

that not so long ago, most of these bombings and other

mayhem, committed by “revolutionary” groups such as

Weatherman, the Black Liberation Army, FALN, and The Family,

often made only local newspapers on page B37, below the fold.

The civil rights struggle and opposition to the Vietnam war had

turned out large crowds and radicalised the campuses, but in

the opinion of many activists, yielded few concrete results.

Indeed, in the 1968 presidential election, pro-war

Democrat Humphrey had been defeated by pro-war Republican

Nixon, with anti-war Democrats McCarthy marginalised and Robert

Kennedy assassinated.

In this bleak environment, a group of leaders of one of the most

radical campus organisations, the Students for a Democratic

Society (SDS), gathered in Chicago to draft what became a sixteen

thousand word manifesto bristling with Marxist jargon that

linked the student movement in the U.S. to Third World guerrilla

insurgencies around the globe. They advocated a Che

Guevara-like guerrilla movement in America led, naturally, by

themselves. They named the manifesto after the Bob Dylan lyric,

“You don't need a weatherman to know which way the wind

blows.” Other SDS members who thought the idea of armed

rebellion in the U.S. absurd and insane quipped, “You

don't need a rectal thermometer to know who the assholes

are.”

The Weatherman faction managed to blow up (figuratively) the SDS

convention in June 1969, splitting the organisation but

effectively taking control of it. They called a massive protest

in Chicago for October. Dubbed the “National

Action”, it would soon become known as the “Days of

Rage”.

Almost immediately the Weatherman plans began to go awry. Their

plans to rally the working class (who the Ivy League Weatherman

élite mocked as “greasers”) got no traction,

with some of their outrageous “actions”

accomplishing little other than landing the perpetrators in the

slammer. Come October, the Days of Rage ended up in farce.

Thousands had been expected, ready to take the fight to the cops

and “oppressors”, but come the day, no more than two

hundred showed up, most SDS stalwarts who already knew one

another. They charged the police and were quickly routed with

six shot (none seriously), many beaten, and more than 120

arrested. Bail bonds alone added up to US$ 2.3 million. It was

a humiliating defeat. The leadership decided it was time to

change course.

So what did this intellectual vanguard of the masses decide to

do? Well, obviously, destroy the SDS (their source of funding

and pipeline of recruitment), go underground, and start blowing

stuff up. This posed a problem, because these middle-class

college kids had no idea where to obtain explosives (they didn't

know that at the time you could buy as much dynamite as you

could afford over the counter in many rural areas with, at most,

showing a driver's license), what to do with it, and how to

build an underground identity. This led to, not Keystone Kops,

but Klueless Kriminal misadventures, culminating in March 1970

when they managed to blow up an entire New York townhouse where

a bomb they were preparing to attack a dance at Fort Dix, New

Jersey detonated prematurely, leaving three of the Weather

collective dead in the rubble. In the aftermath, many Weather

hangers-on melted away.

This did not deter the hard core, who resolved to learn more about

their craft. They issued a communiqué declaring their

solidarity with the oppressed black masses (not one of whom,

oppressed or otherwise, was a member of Weatherman), and vowed

to attack symbols of “Amerikan injustice”. Privately,

they decided to avoid killing people, confining their attacks

to property. And one of their members hit the books to become

a journeyman bombmaker.

The bungling Bolsheviks of Weatherman may have had Marxist

theory down pat, but they were lacking in authenticity, and

acutely aware of it. It was hard for those whose addresses before

going underground were élite universities to present

themselves as oppressed. The best they could do was to identify

themselves with the cause of those they considered victims of

“the system” but who, to date, seemed little

inclined to do anything about it themselves. Those who cheered

on Weatherman, then, considered it significant when, in the

spring of 1971, a new group calling itself the “Black

Liberation Army” (BLA) burst onto the scene with two

assassination-style murders of New York City policemen on

routine duty. Messages delivered after each attack to Harlem

radio station WLIB claimed responsibility. One declared,

Every policeman, lackey or running dog of the ruling class must make his or her choice now. Either side with the people: poor and oppressed, or die for the oppressor. Trying to stop what is going down is like trying to stop history, for as long as there are those who will dare to live for freedom there are men and women who dare to unhorse the emperor. All power to the people.

Politicians, press, and police weren't sure what to make of this. The politicians, worried about the opinion of their black constituents, shied away from anything which sounded like accusing black militants of targeting police. The press, although they'd never write such a thing or speak it in polite company, didn't think it plausible that street blacks could organise a sustained revolutionary campaign: certainly that required college-educated intellectuals. The police, while threatened by these random attacks, weren't sure there was actually any organised group behind the BLA attacks: they were inclined to believe it was a matter of random cop killers attributing their attacks to the BLA after the fact. Further, the BLA had no visible spokesperson and issued no manifestos other than the brief statements after some attacks. This contributed to the mystery, which largely persists to this day because so many participants were killed and the survivors have never spoken out. In fact, the BLA was almost entirely composed of former members of the New York chapter of the Black Panthers, which had collapsed in the split between factions following Huey Newton and those (including New York) loyal to Eldridge Cleaver, who had fled to exile in Algeria and advocated violent confrontation with the power structure in the U.S. The BLA would perpetrate more than seventy violent attacks between 1970 and 1976 and is said to be responsible for the deaths of thirteen police officers. In 1982, they hijacked a domestic airline flight and pocketed a ransom of US$ 1 million. Weatherman (later renamed the “Weather Underground” because the original name was deemed sexist) and the BLA represented the two poles of the violent radicals: the first, intellectual, college-educated, and mostly white, concentrated mostly on symbolic bombings against property, usually with warnings in advance to avoid human casualties. As pressure from the FBI increased upon them, they became increasingly inactive; a member of the New York police squad assigned to them quipped, “Weatherman, Weatherman, what do you do? Blow up a toilet every year or two.” They managed the escape of Timothy Leary from a minimum-security prison in California. Leary basically just walked away, with a group of Weatherman members paid by Leary supporters picking him up and arranging for he and his wife Rosemary to obtain passports under assumed names and flee the U.S. for exile in Algeria with former Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver. The Black Liberation Army, being composed largely of ex-prisoners with records of violent crime, was not known for either the intelligence or impulse control of its members. On several occasions, what should have been merely tense encounters with the law turned into deadly firefights because a BLA militant opened fire for no apparent reason. Had they not been so deadly to those they attacked and innocent bystanders, the exploits of the BLA would have made a fine slapstick farce. As the dour decade of the 1970s progressed, other violent underground groups would appear, tending to follow the model of either Weatherman or the BLA. One of the most visible, it not successful, was the “Symbionese Liberation Army” (SLA), founded by escaped convict and grandiose self-styled revolutionary Daniel DeFreeze. Calling himself “General Field Marshal Cinque”, which he pronounced “sin-kay”, and ending his fevered communications with “DEATH TO THE FASCIST INSECT THAT PREYS UPON THE LIFE OF THE PEOPLE”, this band of murderous bozos struck their first blow for black liberation by assassinating Marcus Foster, the first black superintendent of the Oakland, California school system for his “crimes against the people” of suggesting that police be called into deal with violence in the city's schools and that identification cards be issued to students. Sought by the police for the murder, they struck again by kidnapping heiress, college student, and D-list celebrity Patty Hearst, whose abduction became front page news nationwide. If that wasn't sufficiently bizarre, the abductee eventually issued a statement saying she had chosen to “stay and fight”, adopting the name “Tania”, after the nom de guerre of a Cuban revolutionary and companion of Che Guevara. She was later photographed by a surveillance camera carrying a rifle during a San Francisco bank robbery perpetrated by the SLA. Hearst then went underground and evaded capture until September 1975 after which, when being booked into jail, she gave her occupation as “Urban Guerrilla”. Hearst later claimed she had agreed to join the SLA and participate in its crimes only to protect her own life. She was convicted and sentenced to 35 years in prison, later reduced to 7 years. The sentence was later commuted to 22 months by U.S. President Jimmy Carter and she was released in 1979, and was the recipient of one of Bill Clinton's last day in office pardons in January, 2001. Six members of the SLA, including DeFreeze, died in a house fire during a shootout with the Los Angeles Police Department in May, 1974. Violence committed in the name of independence for Puerto Rico was nothing new. In 1950, two radicals tried to assassinate President Harry Truman, and in 1954, four revolutionaries shot up the U.S. House of Representatives from the visitors' gallery, wounding five congressmen on the floor, none fatally. The Puerto Rican terrorists had the same problem as their Weatherman, BLA, or SLA bomber brethren: they lacked the support of the people. Most of the residents of Puerto Rico were perfectly happy being U.S. citizens, especially as this allowed them to migrate to the mainland to escape the endemic corruption and the poverty it engendered in the island. As the 1960s progressed, the Puerto Rico radicals increasingly identified with Castro's Cuba (which supported them ideologically, if not financially), and promised to make a revolutionary Puerto Rico a beacon of prosperity and liberty like Cuba had become. Starting in 1974, a new Puerto Rican terrorist group, the Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional (FALN) launched a series of attacks in the U.S., most in the New York and Chicago areas. One bombing, that of the Fraunces Tavern in New York in January 1975, killed four people and injured more than fifty. Between 1974 and 1983, a total of more than 130 bomb attacks were attributed to the FALN, most against corporate targets. In 1975 alone, twenty-five bombs went off, around one every two weeks. Other groups, such as the “New World Liberation Front” (NWLF) in northern California and “The Family” in the East continued the chaos. The NWLF, formed originally from remains of the SLA, detonated twice as many bombs as the Weather Underground. The Family carried out a series of robberies, including the deadly Brink's holdup of October 1981, and jailbreaks of imprisoned radicals. In the first half of the 1980s, the radical violence sputtered out. Most of the principals were in prison, dead, or living underground and keeping a low profile. A growing prosperity had replaced the malaise and stagflation of the 1970s and there were abundant jobs for those seeking them. The Vietnam War and draft were receding into history, leaving the campuses with little to protest, and the remaining radicals had mostly turned from violent confrontation to burrowing their way into the culture, media, administrative state, and academia as part of Gramsci's “long march through the institutions”. All of these groups were plagued with the “step two problem”. The agenda of Weatherman was essentially:- Blow stuff up, kill cops, and rob banks.

- ?

- Proletarian revolution.

Wednesday, December 19, 2018

Reading List: Minimanual of the Urban Guerrilla

- Marighella, Carlos. Minimanual of the Urban Guerrilla. Seattle: CreateSpace, [1970] 2018. ISBN 978-1-4664-0680-3.

-

Carlos Marighella joined the Brazilian Communist Party in 1934,

abandoning his studies in civil engineering to become a full

time agitator for communism. He was arrested for subversion

in 1936 and, after release from prison the following year,

went underground. He was recaptured in 1939 and imprisoned

until 1945 as part of an amnesty of political prisoners. He

successfully ran for the federal assembly in 1946 but was

removed from office when the Communist party was again banned

in 1948. Resuming his clandestine life, he served in several

positions in the party leadership and in 1953–1954 visited

China to study the Maoist theory of revolution. In 1964, after a

military coup in Brazil, he was again arrested, being shot in the

process. After being once again released from prison, he broke

with the Communist Party and began to advocate armed revolution

against the military regime, travelling to Cuba to participate

in a conference of Latin American insurgent movements. In 1968,

he formed his own group, the

Ação Libertadora Nacional

(ALN) which, in September 1969, kidnapped U.S. Ambassador

Charles Burke Elbrick, who was eventually released in exchange for

fifteen political prisoners. In November 1969, Marighella was

killed in a police ambush, prompted by a series of robberies and

kidnappings by the ALN.

In June 1969, Marighella published this short book (or

pamphlet: it is just 40 pages with plenty of white space

at the ends of chapters) as a guide for

revolutionaries attacking Brazil's authoritarian regime

in the big cities. There is little or no discussion of the

reasons for the rebellion; the work is addressed to those

already committed to the struggle who seek practical advice

for wreaking mayhem in the streets. Marighella has entirely

bought into the Mao/Guevara theory of revolution: that the

ultimate struggle must take place in the countryside, with

rural peasants rising en masse

against the regime. The problem with this approach was that

the peasants seemed to be more interested in eking out

their subsistence from the land than taking up arms in

support of ideas championed by a few intellectuals in the

universities and big cities. So, Marighella's guide is addressed

to those in the cities with the goal of starting the armed

struggle where there were people indoctrinated in the

communist ideology on which it was based. This seems to

suffer from the “step two problem”. In essence,

his plan is:

- Blow stuff up, rob banks, and kill cops in the big cities.

- ?

- Communist revolution in the countryside.

The urban guerrilla is a man who fights the military dictatorship with arms, using unconventional methods. A political revolutionary, he is a fighter for his country's liberation, a friend of the people and of freedom. The area in which the urban guerrilla acts is in the large Brazilian cities. There are also bandits, commonly known as outlaws, who work in the big cities. Many times assaults by outlaws are taken as actions by urban guerrillas. The urban guerrilla, however, differs radically from the outlaw. The outlaw benefits personally from the actions, and attacks indiscriminately without distinguishing between the exploited and the exploiters, which is why there are so many ordinary men and women among his victims. The urban guerrilla follows a political goal and only attacks the government, the big capitalists, and the foreign imperialists, particularly North Americans.

These fine distinctions tend to be lost upon innocent victims, especially since the proceeds of the bank robberies of which the “urban guerrillas” are so fond are not used to aid the poor but rather to finance still more attacks by the ever-so-noble guerrillas pursuing their “political goal”. This would likely have been an obscure and largely forgotten work of a little-known Brazilian renegade had it not been picked up, translated to English, and published in June and July 1970 by the Berkeley Tribe, a California underground newspaper. It became the terrorist bible of groups including Weatherman, the Black Liberation Army, and Symbionese Liberation Army in the United States, the Red Army Faction in Germany, the Irish Republican Army, the Sandanistas in Nicaragua, and the Palestine Liberation Organisation. These groups embarked on crime and terror campaigns right out of Marighella's playbook with no more thought about step two. They are largely forgotten now because their futile acts had no permanent consequences and their existence was an embarrassment to the élites who largely share their pernicious ideology but have chosen to advance it through subversion, not insurrection. A Kindle edition is available from a different publisher. You can read the book on-line for free at the Marxists Internet Archive.

Monday, December 17, 2018

Reading List: Losing Mars

- Cawdron, Peter. Losing Mars. Brisbane, Australia: Independent, 2018. ISBN 978-1-7237-4729-8.

-

Peter Cawdron has established himself as the contemporary grandmaster

of first contact science fiction. In a series of novels including

Anomaly (December 2011),

Xenophobia (August 2013),

Little Green Men (September 2013),

Feedback (February 2014),

and My Sweet Satan (September 2014),

he has explored the first encounter of humans with extraterrestrial

life in a variety of scenarios, all with twists and turns

that make you question the definition of life and intelligence.

This novel is set on Mars, where a nominally international but

strongly NASA-dominated station has been set up by the

six-person crew first to land on the red planet. The crew of

Shepard station, three married couples, bring a

variety of talents to their multi-year mission of exploration:

pilot, engineer, physician, and even botanist: Cory Anderson

(the narrator) is responsible for the greenhouse which will feed

the crew during their mission. They have a fully-fueled Mars

Return Vehicle, based upon NASA's Orion capsule, ready to go,

and their ticket back to Earth, the Schiaparelli

return stage, waiting in Mars orbit, but orbital mechanics

dictates when they can return to Earth, based on the two-year

cycle of Earth-Mars transfer opportunities. The crew is acutely

aware that the future of Mars exploration rests on their

shoulders: failure, whether a tragedy in which they were lost,

or even cutting their mission short, might result in

“losing Mars” in the same way humanity abandoned

the Moon for fifty years after “flags and

footprints” visits had accomplished their chest-beating

goal.

The Shepard crew are confronted with a crisis not

of their making when a Chinese mission, completely unrelated

to theirs, attempting to do “Mars on a shoestring”

by exploring its moon Phobos, faces disaster when a

poorly-understood calamity kills two of its four crew and

disables their spacecraft. The two surviving taikonauts show

life signs on telemetry but have not communicated with their

mission control and, with their ship disabled, are certain to

die when their life support consumables are exhausted.

The crew, in consultation with NASA, conclude the only way to

mount a rescue mission is for the pilot and Cory, the only

crew member who can be spared, to launch in the return vehicle,

rendezvous with the Schiaparelli, use it to

match orbits with the Chinese ship, rescue the survivors,

and then return to Earth with them. (The return vehicle is unable

to land back on Mars, being unequipped for a descent and soft

landing through its thin atmosphere.) This will leave the four

remaining crew of the Shepard with no way home

until NASA can send a rescue mission, which will take two years to

arrive at Mars. However unappealing the prospect, they conclude

that abandoning the Chinese crew to die when rescue was possible

would be inhuman, and proceed with the plan.

It is only after arriving at Phobos, after the half-way point in

the book, that things begin to get distinctly weird and we suddenly

realise that Peter Cawdron is not writing a novelisation of a

Kerbal Space Program

rescue scenario but is rather up to his old tricks and there

is much more going on here than you've imagined from the story

so far.

Babe Ruth hit 714 home runs, but he struck out 1,330 times. For

me, this story is a swing and a miss. It takes a long, long time

to get going, and we must wade through a great deal of social

justice virtue signalling to get there. (Lesbians in space?

Who could have imagined? Oh, right….) Once we get to

the “good part”, the narrative is related in a

fractured manner reminiscent of Vonnegut (I'm trying to avoid

spoilers—you'll know what I'm talking about if you make it

that far). And the copy editing and fact checking…oh, dear.

There are no fewer than seven idiot “it's/its”

bungles, two on one page. A solar powered aircraft is said to have

“turboprop engines”. Alan Shepard's suborbital mission

is said to have been launched on a “prototype Redstone

rocket” (it wasn't), which is described as an

“intercontinental ballistic missile” (it was a short range

missile with a maximum range of 323 km), which subjected the astronaut

to “nine g's [sic] launching” (it was actually 6.3 g),

with reentry g loads “more than that of the gas giant Saturn”

(which is correct, but local gravity on Saturn is just 1.065 g, as

the planet is very large and less dense than water). Military

officers who defy orders are tried by a court martial, not “court

marshaled”. The

Mercury-Atlas 3

launch failure which Shepard witnessed at the Cape did not “[end]

up in a fireball a couple of hundred feet above the concrete”: in

fact it was destroyed by ground command forty-three seconds after

launch at an altitude of several kilometres due to a guidance system

failure, and the launch escape system saved the spacecraft and would

have allowed an astronaut, had one been on board, to land safely.

It's “bungee” cord, not “Bungie”. “Navy”

is not an acronym, and hence is not written “NAVY”. The Juno

orbiter at Jupiter does not “broadcast with the strength of a

cell phone”; it has a 25 watt transmitter which is between twelve

and twenty-five times more powerful than the maximum power of a mobile

phone. He confuses “ecliptic” and “elliptical”, and

states that the velocity of a spacecraft decreases as it approaches

closer to a body in free fall (it increases). A spacecraft is said to be

“accelerating at fifteen meters per second” which is a unit

of velocity, not acceleration. A daughter may be the spitting image of

her mother, but not “the splitting image”. Thousands of tiny wires

do not “rap” around a plastic coated core, they “wrap”,

unless they are special hip-hop wires which NASA has never approved for

space flight. We do not live in a “barreled galaxy”, but

rather a barred spiral galaxy.

Now, you may think I'm being harsh in pointing out these goofs which

are not, after all, directly relevant to the plot of the novel. But

errors of this kind, all of which could be avoided by research no more

involved than looking things up in Wikipedia or consulting a guide to

English usage, are indicative of a lack of attention to detail which,

sadly, is also manifest in the main story line. To discuss these we

must step behind the curtain.

Spoiler warning: Plot and/or ending details follow.It is implausible in the extreme that the Schiaparelli would have sufficient extra fuel to perform a plane change maneuver from its orbital inclination of nearly twenty degrees to the near-equatorial orbit of Phobos, then raise its orbit to rendezvous with the moon. The fuel on board the Schiaparelli would have been launched from Earth, and would be just sufficient to return to Earth without any costly maneuvers in Mars orbit. The cost of launching such a large additional amount of fuel, not to mention the larger tanks to hold it, would be prohibitive. (We're already in a spoiler block, but be warned that the following paragraph is a hideous spoiler of the entire plot.) Cory's ethical dilemma, on which the story turns, is whether to reveal the existence of the advanced technology alien base on Phobos to a humanity which he believes unprepared for such power and likely to use it to destroy themselves. OK, fine, that's his call (and that of Hedy, who also knows enough to give away the secret). But in the conclusion, we're told that, fifty years after the rescue mission, there's a thriving colony on Mars with eight thousand people in two subsurface towns, raising families. How probable is it, even if not a word was said about what happened on Phobos, that this thriving colony and the Earth-based space program which supported it would not, over half a century, send another exploration mission to Phobos, which is scientifically interesting in its own right? And given what Cory found there, any mission which investigated Phobos would have found what he did. Finally, in the Afterword, the author defends his social justice narrative as follows.Peter Cawdron's earlier novels have provided many hours of thought-provoking entertainment, spinning out the possibilities of first contact. The present book…didn't, although it was good for a few laughs. I'm not going to write off a promising author due to one strike-out. I hope his next outing resumes the home run streak. A Kindle edition is available, which is free for Kindle Unlimited subscribers.

At times, I've been criticized for “jumping on the [liberal] bandwagon” on topics like gay rights and Black Lives Matter across a number of books, but, honestly, it's the 21st century—the cruelty that still dominates how we humans deal with each other is petty and myopic. Any contact with an intelligent extraterrestrial species will expose not only a vast technological gulf, but a moral one as well.

Well, maybe, but isn't it equally likely that when they arrive in their atomic space cars and imbibe what passes for culture and morality among the intellectual élite of the global Davos party and how obsessed these talking apes seem to be about who is canoodling whom with what, that after they stop laughing they may decide that we are made of atoms which they can use for something else.Spoilers end here.

Saturday, December 15, 2018

Reading List: Stalin, Vol. 1: Paradoxes of Power, 1878-1928.

- Kotkin, Stephen. Stalin, Vol. 1: Paradoxes of Power, 1878–1928. New York: Penguin Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0-14-312786-4.

- In a Levada Center poll in 2017, Russians who responded named Joseph Stalin the “most outstanding person” in world history. Now, you can argue about the meaning of “outstanding”, but it's pretty remarkable that citizens of a country whose chief of government (albeit several regimes ago) presided over an entirely avoidable famine which killed millions of citizens of his country, ordered purges which executed more than 700,000 people, including senior military leadership, leaving his nation unprepared for the German attack in 1941, which would, until the final victory, claim the lives of around 27 million Soviet citizens, military and civilian, would be considered an “outstanding person” as opposed to a super-villain. The story of Stalin's career is even less plausible, and should give pause to those who believe history can be predicted without the contingency of things that “just happen”. Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili (the author uses Roman alphabet transliterations of all individuals' names in their native languages, which can occasionally be confusing when they later Russified their names) was born in 1878 in the town of Gori in the Caucasus. Gori, part of the territory of Georgia which had long been ruled by the Ottoman Empire, had been seized by Imperial Russia in a series of bloody conflicts ending in the 1860s with complete incorporation of the territory into the Czar's empire. Ioseb, who was called by the Georgian dimunitive “Sosa” throughout his youth, was the third son born to his parents, but, as both of his older brothers had died not long after birth, was raised as an only child. Sosa's father, Besarion Jughashvili (often written in the Russian form, Vissarion) was a shoemaker with his own shop in Gori but, as time passed his business fell on hard times and he closed the shop and sought other work, ending his life as a vagrant. Sosa's mother, Ketevan “Keke” Geladze, was ambitious and wanted the best for her son, and left her husband and took a variety of jobs to support the family. She arranged for eight year old Sosa to attend Russian language lessons given to the children of a priest in whose house she was boarding. Knowledge of Russian was the key to advancement in Czarist Georgia, and he had a head start when Keke arranged for him to be enrolled in the parish school's preparatory and four year programs. He was the first member of either side of his family to attend school and he rose to the top of his class under the patronage of a family friend, “Uncle Yakov” Egnatashvili. After graduation, his options were limited. The Russian administration, wary of the emergence of a Georgian intellectual class that might champion independence, refused to establish a university in the Caucasus. Sosa's best option was the highly selective Theological Seminary in Tiflis where he would prepare, in a six year course, for life as a parish priest or teacher in Georgia but, for those who graduated near the top, could lead to a scholarship at a university in another part of the empire. He took the examinations and easily passed, gaining admission, petitioning and winning a partial scholarship that paid most of his fees. “Uncle Yakov” paid the rest, and he plunged into his studies. Georgia was in the midst of an intense campaign of Russification, and Sosa further perfected his skills in the Russian language. Although completely fluent in spoken and written Russian along with his native Georgian (the languages are completely unrelated, having no more in common than Finnish and Italian), he would speak Russian with a Georgian accent all his life and did not publish in the Russian language until he was twenty-nine years old. Long a voracious reader, at the seminary Sosa joined a “forbidden literature” society which smuggled in and read works, not banned by the Russian authorities, but deemed unsuitable for priests in training. He read classics of Russian, French, English, and German literature and science, including Capital by Karl Marx. The latter would transform his view of the world and path in life. He made the acquaintance of a former seminarian and committed Marxist, Lado Ketskhoveli, who would guide his studies. In August 1898, he joined the newly formed “Third Group of Georgian Marxists”—many years later Stalin would date his “party card” to then. Prior to 1905, imperial Russia was an absolute autocracy. The Czar ruled with no limitations on his power. What he decreed and ordered his functionaries to do was law. There was no parliament, political parties, elected officials of any kind, or permanent administrative state that did not serve at the pleasure of the monarch. Political activity and agitation were illegal, as were publishing and distributing any kind of political literature deemed to oppose imperial rule. As Sosa became increasingly radicalised, it was only a short step from devout seminarian to underground agitator. He began to neglect his studies, became increasingly disrespectful to authority figures, and, in April 1899, left the seminary before taking his final examinations. Saddled with a large debt to the seminary for leaving without becoming a priest or teacher, he drifted into writing articles for small, underground publications associated with the Social Democrat movement, at the time the home of most Marxists. He took to public speaking and, while eschewing fancy flights of oratory, spoke directly to the meetings of workers he addressed in their own dialect and terms. Inevitably, he was arrested for “incitement to disorder and insubordination against higher authority” in April 1902 and jailed. After fifteen months in prison at Batum, he was sentenced to three years of internal exile in Siberia. In January 1904 he escaped and made it back to Tiflis, in Georgia, where he resumed his underground career. By this time the Social Democratic movement had fractured into Lenin's Bolshevik faction and the larger Menshevik group. Sosa, who during his imprisonment had adopted the revolutionary nickname “Koba”, after the hero in a Georgian novel of revenge, continued to write and speak and, in 1905, after the Czar was compelled to cede some of his power to a parliament, organised Battle Squads which stole printing equipment, attacked government forces, and raised money through protection rackets targeting businesses. In 1905, Koba Jughashvili was elected one of three Bolshevik delegates from Georgia to attend the Third Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party in Tampere, Finland, then part of the Russian empire. It was there he first met Lenin, who had been living in exile in Switzerland. Koba had read Lenin's prolific writings and admired his leadership of the Bolshevik cause, but was unimpressed in this first in-person encounter. He vocally took issue with Lenin's position that Bolsheviks should seek seats in the newly-formed State Duma (parliament). When Lenin backed down in the face of opposition, he said, “I expected to see the mountain eagle of our party, a great man, not only politically but physically, for I had formed for myself a picture of Lenin as a giant, as a stately representative figure of a man. What was my disappointment when I saw the most ordinary individual, below average height, distinguished from ordinary mortals by, literally, nothing.” Returning to Georgia, he resumed his career as an underground revolutionary including, famously, organising a robbery of the Russian State Bank in Tiflis in which three dozen people were killed and two dozen more injured, “expropriating” 250,000 rubles for the Bolshevik cause. Koba did not participate directly, but he was the mastermind of the heist. This and other banditry, criminal enterprises, and unauthorised publications resulted in multiple arrests, imprisonments, exiles to Siberia, escapes, re-captures, and life underground in the years that followed. In 1912, while living underground in Saint Petersburg after yet another escape, he was named the first editor of the Bolshevik party's new daily newspaper, Pravda, although his name was kept secret. In 1913, with the encouragement of Lenin, he wrote an article titled “Marxism and the National Question” in which he addressed how a Bolshevik regime should approach the diverse ethnicities and national identities of the Russian Empire. As a Georgian Bolshevik, Jughashvili was seen as uniquely qualified and credible to address this thorny question. He published the article under the nom de plume “K. [for Koba] Stalin”, which literally translated, meant “Man of Steel” and paralleled Lenin's pseudonym. He would use this name for the rest of his life, reverting to the Russified form of his given name, “Joseph” instead of the nickname Koba (by which his close associates would continue to address him informally). I shall, like the author, refer to him subsequently as “Stalin”. When Russia entered the Great War in 1914, events were set into motion which would lead to the end of Czarist rule, but Stalin was on the sidelines: in exile in Siberia, where he spent much of his time fishing. In late 1916, as manpower shortages became acute, exiled Bolsheviks including Stalin received notices of conscription into the army, but when he appeared at the induction centre he was rejected due to a crippled left arm, the result of a childhood injury. It was only after the abdication of the Czar in the February Revolution of 1917 that he returned to Saint Petersburg, now renamed Petrograd, and resumed his work for the Bolshevik cause. In April 1917, in elections to the Bolshevik Central Committee, Stalin came in third after Lenin (who had returned from exile in Switzerland) and Zinoviev. Despite having been out of circulation for several years, Stalin's reputation from his writings and editorship of Pravda, which he resumed, elevated him to among the top rank of the party. As Kerensky's Provisional Government attempted to consolidate its power and continue the costly and unpopular war, Stalin and Trotsky joined Lenin's call for a Bolshevik coup to seize power, and Stalin was involved in all aspects of the eventual October Revolution, although often behind the scenes, while Lenin was the public face of the Bolshevik insurgency. After seizing power, the Bolsheviks faced challenges from all directions. They had to disentangle Russia from the Great War without leaving the country open to attack and territorial conquest by Germany or Poland. Despite their ambitious name, they were a minority party and had to subdue domestic opposition. They took over a country which the debts incurred by the Czar to fund the war had effectively bankrupted. They had to exert their control over a sprawling, polyglot empire in which, outside of the big cities, their party had little or no presence. They needed to establish their authority over a military in which the officer corps largely regarded the Czar as their legitimate leader. They must restore agricultural production, severely disrupted by levies of manpower for the war, before famine brought instability and the risk of a counter-coup. And for facing these formidable problems, all at the same time, they were utterly unprepared. The Bolsheviks were, to a man (and they were all men), professional revolutionaries. Their experience was in writing and publishing radical tracts and works of Marxist theory, agitating and organising workers in the cities, carrying out acts of terror against the regime, and funding their activities through banditry and other forms of criminality. There was not a military man, agricultural expert, banker, diplomat, logistician, transportation specialist, or administrator among them, and suddenly they needed all of these skills and more, plus the ability to recruit and staff an administration for a continent-wide empire. Further, although Lenin's leadership was firmly established and undisputed, his subordinates were all highly ambitious men seeking to establish and increase their power in the chaotic and fluid situation. It was in this environment that Stalin made his mark as the reliable “fixer”. Whether it was securing levies of grain from the provinces, putting down resistance from counter-revolutionary White forces, stamping out opposition from other parties, developing policies for dealing with the diverse nations incorporated into the Russian Empire (indeed, in a real sense, it was Stalin who invented the Soviet Union as a nominal federation of autonomous republics which, in fact, were subject to Party control from Moscow), or implementing Lenin's orders, even when he disagreed with them, Stalin was on the job. Lenin recognised Stalin's importance as his right hand man by creating the post of General Secretary of the party and appointing him to it. This placed Stalin at the centre of the party apparatus. He controlled who was hired, fired, and promoted. He controlled access to Lenin (only Trotsky could see Lenin without going through Stalin). This was a finely-tuned machine which allowed Lenin to exercise absolute power through a party machine which Stalin had largely built and operated. Then, in May of 1922, the unthinkable happened: Lenin was felled by a stroke which left him partially paralysed. He retreated to his dacha at Gorki to recuperate, and his communication with the other senior leadership was almost entirely through Stalin. There had been no thought of or plan for a succession after Lenin (he was only fifty-two at the time of his first stroke, although he had been unwell for much of the previous year). As Lenin's health declined, ending in his death in January 1924, Stalin increasingly came to run the party and, through it, the government. He had appointed loyalists in key positions, who saw their own careers as linked to that of Stalin. By the end of 1924, Stalin began to move against the “Old Bolsheviks” who he saw as rivals and potential threats to his consolidation of power. When confronted with opposition, on three occasions he threatened to resign, each exercise in brinksmanship strengthening his grip on power, as the party feared the chaos that would ensue from a power struggle at the top. His status was reflected in 1925 when the city of Tsaritsyn was renamed Stalingrad. This ascent to supreme power was not universally applauded. Felix Dzierzynski (Polish born, he is often better known by the Russian spelling of his name, Dzerzhinsky) who, as the founder of the Soviet secret police (Cheka/GPU/OGPU) knew a few things about dictatorship, warned in 1926, the year of his death, that “If we do not find the correct line and pace of development our opposition will grow and the country will get its dictator, the grave digger of the revolution irrespective of the beautiful feathers on his costume.” With or without feathers, the dictatorship was beginning to emerge. In 1926 Stalin published “On Questions of Leninism” in which he introduced the concept of “Socialism in One Country” which, presented as orthodox Leninist doctrine (which it wasn't), argued that world revolution was unnecessary to establish communism in a single country. This set the stage for the collectivisation of agriculture and rapid industrialisation which was to come. In 1928, what was to be the prototype of the show trials of the 1930s opened in Moscow, the Shakhty trial, complete with accusations of industrial sabotage (“wrecking”), denunciations of class enemies, and Andrei Vyshinsky presiding as chief judge. Of the fifty-three engineers accused, five were executed and forty-four imprisoned. A country desperately short on the professionals its industry needed to develop had begin to devour them. It is a mistake to regard Stalin purely as a dictator obsessed with accumulating and exercising power and destroying rivals, real or imagined. The one consistent theme throughout Stalin's career was that he was a true believer. He was a devout believer in the Orthodox faith while at the seminary, and he seamlessly transferred his allegiance to Marxism once he had been introduced to its doctrines. He had mastered the difficult works of Marx and could cite them from memory (as he often did spontaneously to buttress his arguments in policy disputes), and went on to similarly internalise the work of Lenin. These principles guided his actions, and motivated him to apply them rigidly, whatever the cost may be. Starting in 1921, Lenin had introduced the New Economic Policy, which lightened state control over the economy and, in particular, introduced market reforms in the agricultural sector, resulting in a mixed economy in which socialism reigned in big city industries, but in the countryside the peasants operated under a kind of market economy. This policy had restored agricultural production to pre-revolutionary levels and largely ended food shortages in the cities and countryside. But to a doctrinaire Marxist, it seemed to risk destruction of the regime. Marx believed that the political system was determined by the means of production. Thus, accepting what was essentially a capitalist economy in the agricultural sector was to infect the socialist government with its worst enemy. Once Stalin had completed his consolidation of power, he then proceeded as Marxist doctrine demanded: abolish the New Economic Policy and undertake the forced collectivisation of agriculture. This began in 1928. And it is with this momentous decision that the present volume comes to an end. This massive work (976 pages in the print edition) is just the first in a planned three volume biography of Stalin. The second volume, Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929–1941, was published in 2017 and the concluding volume is not yet completed. Reading this book, and the entire series, is a major investment of time in a single historical figure. But, as the author observes, if you're interested in the phenomenon of twentieth century totalitarian dictatorship, Stalin is the gold standard. He amassed more power, exercised by a single person with essentially no checks or limits, over more people and a larger portion of the Earth's surface than any individual in human history. He ruled for almost thirty years, transformed the economy of his country, presided over deliberate famines, ruthless purges, and pervasive terror that killed tens of millions, led his country to victory at enormous cost in the largest land conflict in history and ended up exercising power over half of the European continent, and built a military which rivaled that of the West in a bipolar struggle for global hegemony. It is impossible to relate the history of Stalin without describing the context in which it occurred, and this is as much a history of the final days of imperial Russia, the revolutions of 1917, and the establishment and consolidation of Soviet power as of Stalin himself. Indeed, in this first volume, there are lengthy parts of the narrative in which Stalin is largely offstage: in prison, internal exile, or occupied with matters peripheral to the main historical events. The level of detail is breathtaking: the Bolsheviks seem to have been as compulsive record-keepers as Germans are reputed to be, and not only are the votes of seemingly every committee meeting recorded, but who voted which way and why. There are more than two hundred pages of end notes, source citations, bibliography, and index. If you are interested in Stalin, the Soviet Union, the phenomenon of Bolshevism, totalitarian dictatorship, or how destructive madness can grip a civilised society for decades, this is an essential work. It is unlikely it will ever be equalled.

Sunday, December 2, 2018

Reading List: Apollo 8

- Kluger, Jeffrey. Apollo 8. New York: Picador, 2017. ISBN 978-1-250-18251-7.

-

As the tumultuous year 1968 drew to a close, NASA faced a

serious problem with the Apollo project. The Apollo missions

had been carefully planned to test the Saturn V booster

rocket and spacecraft (Command/Service Module [CSM] and Lunar

Module [LM]) in a series of increasingly ambitious missions,

first in low Earth orbit (where an immediate return to Earth

was possible in case of problems), then in an elliptical

Earth orbit which would exercise the on-board guidance and

navigation systems, followed by lunar orbit, and finally

proceeding to the first manned lunar landing. The Saturn V

had been tested in two unmanned “A” missions:

Apollo 4

in November 1967 and

Apollo 6

in April 1968.

Apollo 5

was a “B” mission, launched on a smaller Saturn 1B

booster in January 1968, to test an unmanned early model of

the Lunar Module in low Earth orbit, primarily to verify the

operation of its engines and separation of the descent and

ascent stages.

Apollo 7,

launched in October 1968 on a Saturn 1B, was the first manned

flight of the Command and Service modules and tested them

in low Earth orbit for almost 11 days in a “C”

mission.

Apollo 8 was planned to be the “D” mission,

in which the Saturn V, in its first manned flight, would

launch the Command/Service and Lunar modules into low

Earth orbit, where the crew, commanded by Gemini veteran

James McDivitt, would simulate the maneuvers of a lunar

landing mission closer to home. McDivitt's crew was trained

and ready to go in December 1968. Unfortunately, the lunar

module wasn't. The lunar module scheduled for Apollo 8, LM-3,

had been delivered to the Kennedy Space Center in June of

1968, but was, to put things mildly, a mess. Testing at the

Cape discovered more than a hundred serious defects, and by

August it was clear that there was no way LM-3 would be ready

for a flight in 1968. In fact, it would probably slip to February

or March 1969. This, in turn, would push the planned “E”

mission, for which the crew of commander Frank Borman,

command module pilot James Lovell, and lunar module pilot

William Anders were training, aimed at testing the

Command/Service and Lunar modules in an elliptical Earth

orbit venturing as far as 7400 km from the planet and originally

planned for March 1969, three months later, to June,

delaying all subsequent planned missions and placing the goal

of landing before the end of 1969 at risk.

But NASA were not just racing the clock—they were also

racing the Soviet Union. Unlike Apollo, the Soviet space

program was highly secretive and NASA had to go on whatever

scraps of information they could glean from Soviet publications,

the intelligence community, and independent tracking of Soviet

launches and spacecraft in flight. There were, in fact, two

Soviet manned lunar programmes running in parallel.

The first, internally called the

Soyuz 7K-L1

but dubbed “Zond” for public consumption,

used a modified version of the Soyuz spacecraft launched on

a Proton booster and was intended to carry two cosmonauts

on a fly-by mission around the Moon. The craft would fly out

to the Moon, use its gravity to swing around the far side,

and return to Earth. The Zond lacked the propulsion capability

to enter lunar orbit. Still, success would allow the Soviets to

claim the milestone of first manned mission to the Moon. In

September 1968

Zond 5

successfully followed this mission profile and safely returned

a crew cabin containing tortoises, mealworms, flies, and

plants to Earth after their loop around the Moon. A U.S.

Navy destroyer observed recovery of the re-entry capsule in

the Indian Ocean. Clearly, this was preparation for a

manned mission which might occur on any lunar launch window.

(The Soviet manned lunar landing project was actually far behind

Apollo, and would not launch its

N1 booster

on that first, disastrous, test flight until February 1969. But

NASA did not know this in 1968.) Every slip in the Apollo

program increased the probability of its being scooped so close

to the finish line by a successful Zond flyby mission.

These were the circumstances in August 1968 when what amounted

to a cabal of senior NASA managers including George Low, Chris

Kraft, Bob Gilruth, and later joined by Wernher von Braun and

chief astronaut Deke Slayton, began working on an alternative.

They plotted in secret, beneath the radar and unbeknownst to

NASA administrator Jim Webb and his deputy for manned space

flight, George Mueller, who were both out of the country,

attending an international conference in Vienna. What they were

proposing was breathtaking in its ambition and risk. They

envisioned taking Frank Borman's crew, originally scheduled for

Apollo 9, and putting them into an accelerated training program

to launch on the Saturn V and Apollo spacecraft currently

scheduled for Apollo 8. They would launch without a Lunar

Module, and hence be unable to land on the Moon or test that

spacecraft. The original idea was to perform a Zond-like flyby,

but this was quickly revised to include going into orbit around

the Moon, just as a landing mission would do. This would allow

retiring the risk of many aspects of the full landing mission

much earlier in the program than originally scheduled, and would

also allow collection of precision data on the lunar

gravitational field and high resolution photography of candidate

landing sites to aid in planning subsequent missions. The lunar

orbital mission would accomplish all the goals of the originally

planned “E” mission and more, allowing that mission

to be cancelled and therefore not requiring an additional

booster and spacecraft.

But could it be done? There were a multitude of requirements,

all daunting. Borman's crew, training toward a launch in early

1969 on an Earth orbit mission, would have to complete training

for the first lunar mission in just sixteen weeks. The Saturn V

booster, which suffered multiple near-catastrophic engine

failures in its second flight on Apollo 6, would have to be

cleared for its first manned flight. Software for the on-board

guidance computer and for Mission Control would have to be

written, tested, debugged, and certified for a lunar mission

many months earlier than previously scheduled. A flight plan

for the lunar orbital mission would have to be written from

scratch and then tested and trained in simulations with Mission

Control and the astronauts in the loop. The decision to fly

Borman's crew instead of McDivitt's was to avoid wasting the

extensive training the latter crew had undergone in LM systems

and operations by assigning them to a mission without an LM.

McDivitt concurred with this choice: while it might be nice to

be among the first humans to see the far side of the Moon with

his own eyes, for a test pilot the highest responsibility and

honour is to command the first flight of a new vehicle (the LM),

and he would rather skip the Moon mission and fly later than

lose that opportunity. If the plan were approved, Apollo 8 would

become the lunar orbit mission and the Earth orbit test of

the LM would be re-designated Apollo 9 and fly whenever the LM

was ready.

While a successful lunar orbital mission on Apollo 8 would

demonstrate many aspects of a full lunar landing mission, it

would also involve formidable risks. The Saturn V, making only

its third flight, was coming off a very bad outing in Apollo 6

whose failures might have injured the crew, damaged the

spacecraft hardware, and precluded a successful mission to the

Moon. While fixes for each of these problems had been

implemented, they had never been tested in flight, and there was

always the possibility of new problems not previously seen.

The Apollo Command and Service modules, which would take them to

the Moon, had not yet flown a manned mission and would not until

Apollo 7, scheduled for October 1968. Even if Apollo 7 were a

complete success (which was considered a prerequisite for

proceeding), Apollo 8 would be only the second manned flight of

the Apollo spacecraft, and the crew would have to rely upon the

functioning of its power generation, propulsion, and life

support systems for a mission lasting six days. Unlike an Earth

orbit mission, if something goes wrong en route to or returning

from the Moon, you can't just come home immediately. The

Service Propulsion System on the Service Module would have to

work perfectly when leaving lunar orbit or the crew would be

marooned forever or crash on the Moon. It would only have

been tested previously in one manned mission and there was no

backup (although the single engine did incorporate substantial

redundancy in its design).

The spacecraft guidance, navigation, and control system and

its Apollo Guidance Computer hardware and software, upon which

the crew would have to rely to navigate to and from the Moon,

including the critical engine burns to enter and leave lunar

orbit while behind the Moon and out of touch with Mission

Control, had never been tested beyond Earth orbit.

The mission would go to the Moon without a Lunar Module. If

a problem developed en route to the Moon which disabled the

Service Module (as would happen to Apollo 13 in April 1970),

there would be no LM to serve as a lifeboat and the crew would

be doomed.

When the high-ranking conspirators presented their audacious

plan to their bosses, the reaction was immediate. Manned

spaceflight chief Mueller immediately said, “Can't do

that! That's craziness!” His boss, administrator James

Webb, said “You try to change the entire direction of the

program while I'm out of the country?” Mutiny is a strong

word, but this seemed to verge upon it. Still, Webb and Mueller

agreed to meet with the lunar cabal in Houston on August 22.

After a contentious meeting, Webb agreed to proceed with the

plan and to present it to President Johnson, who was almost

certain to approve it, having great confidence in Webb's

management of NASA. The mission was on.

It was only then that Borman and his crewmembers Lovell and

Anders learned of their reassignment. While Anders was

disappointed at the prospect of being the Lunar Module Pilot

on a mission with no Lunar Module, the prospect of being on

the first flight to the Moon and entrusted with observation and

photography of lunar landing sites more than made up for it.

They plunged into an accelerated training program to get ready

for the mission.

NASA approached the mission with its usual “can-do”

approach and public confidence, but everybody involved was

acutely aware of the risks that were being taken. Susan

Borman, Frank's wife, privately asked Chris Kraft, director

of Flight Operations and part of the group who advocated

sending Apollo 8 to the Moon, with a reputation as a

plain-talking straight shooter, “I really want to

know what you think their chances are of coming home.”

Kraft responded, “You really mean that, don't you?”

“Yes,” she replied, “and you know I do.”

Kraft answered, “Okay. How's fifty-fifty?”

Those within the circle, including the crew, knew what they

were biting off.

The launch was scheduled for December 21, 1968. Everybody would

be working through Christmas, including the twelve ships and

thousands of sailors in the recovery fleet, but lunar launch

windows are set by the constraints of celestial mechanics,

not human holidays. In November, the Soviets had flown

Zond 6,

and it had demonstrated the

“double dip” re-entry trajectory required for

human lunar missions. There were two system failures which

killed the animal test subjects on board, but these were

covered up and the mission heralded as a great success. From

what NASA knew, it was entirely possible the next launch

would be with cosmonauts bound for the Moon.

Space launches were exceptional public events in the 1960s,

and the first flight of men to the Moon, just about a

hundred years after Jules Verne envisioned three men setting out

for the Moon from central Florida in a “cylindro-conical

projectile” in

De

la terre à la lune

(From the Earth

to the Moon), similarly engaging the world, the

launch of Apollo 8 attracted around a quarter of a million people

to watch the spectacle in person and hundreds of millions watching

on television both in North America and around the globe, thanks to

the newfangled technology of communication satellites. Let's tune

in to CBS television and relive this singular event with Walter

Cronkite.

CBS coverage of the Apollo 8 launch

Now we step inside Mission Control and listen in on the Flight Director's audio loop during the launch, illustrated with imagery and simulations.