« January 2018 | Main | March 2018 »

Thursday, February 15, 2018

Reading List: The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare

- Lewis, Damien. The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare. New York: Quercus, 2015. ISBN 978-1-68144-392-8.

- After becoming prime minister in May 1940, one of Winston Churchill's first acts was to establish the Special Operations Executive (SOE), which was intended to conduct raids, sabotage, reconnaissance, and support resistance movements in Axis-occupied countries. The SOE was not part of the military: it was a branch of the Ministry of Economic Warfare and its very existence was a state secret, camouflaged under the name “Inter-Service Research Bureau”. Its charter was, as Churchill described it, to “set Europe ablaze”. The SOE consisted, from its chief, Brigadier Colin McVean Gubbins, who went by the designation “M”, to its recruits, of people who did not fit well with the regimentation, hierarchy, and constraints of life in the conventional military branches. They could, in many cases, be easily mistaken for blackguards, desperadoes, and pirates, and that's precisely what they were in the eyes of the enemy—unconstrained by the rules of warfare, striking by stealth, and sowing chaos, mayhem, and terror among occupation troops who thought they were far from the front. Leading some of the SOE's early exploits was Gustavus “Gus” March-Phillipps, founder of the British Army's Small Scale Raiding Force, and given the SOE designation “Agent W.01”, meaning the first agent assigned to the west Africa territory with the leading zero identifying him as “trained and licensed to use all means to liquidate the enemy”—a license to kill. The SOE's liaison with the British Navy, tasked with obtaining support for its operations and providing cover stories for them, was a fellow named Ian Fleming. One of the SOE's first and most daring exploits was Operation Postmaster, with the goal of seizing German and Italian ships anchored in the port of Santa Isabel on the Spanish island colony of Fernando Po off the coast of west Africa. Given the green light by Churchill over the strenuous objections of the Foreign Office and Admiralty, who were concerned about the repercussions if British involvement in what amounted to an act of piracy in a neutral country were to be disclosed, the operation was mounted under the strictest secrecy and deniability, with a cover story prepared by Ian Fleming. Despite harrowing misadventures along the way, the plan was a brilliant success, capturing three ships and their crews and delivering them to the British-controlled port of Lagos without any casualties. Vindicated by the success, Churchill gave the SOE the green light to raid Nazi occupation forces on the Channel Islands and the coast of France. On his first mission in Operation Postmaster was Anders Lassen, an aristocratic Dane who enlisted as a private in the British Commandos after his country was occupied by the Nazis. With his silver-blond hair, blue eyes, and accent easily mistaken for German, Lassen was apprehended by the Home Guard on several occasions while on training missions in Britain and held as a suspected German spy until his commanders intervened. Lassen was given a field commission, direct from private to second lieutenant, immediately after Operation Postmaster, and went on to become one of the most successful leaders of special operations raids in the war. As long as Nazis occupied his Danish homeland, he was possessed with a desire to kill as many Nazis as possible, wherever and however he could, and when in combat was animated by a berserker drive and ability to improvise that caused those who served with him to call him the “Danish Viking”. This book provides a look into the operations of the SOE and its successor organisations, the Special Air Service and Special Boat Service, seen through the career of Anders Lassen. So numerous were special operations, conducted in many theatres around the world, that this kind of focus is necessary. Also, attrition in these high-risk raids, often far behind enemy lines, was so high there are few individuals one can follow throughout the war. As the war approached its conclusion, Lassen was the only surviving participant in Operation Postmaster, the SOE's first raid. Lassen went on to lead raids against Nazi occupation troops in the Channel Islands, leading Churchill to remark, “There comes from the sea from time to time a hand of steel which plucks the German sentries from their posts with growing efficiency.” While these “butcher-and-bolt” raids could not liberate territory, they yielded prisoners, code books, and radio contact information valuable to military intelligence and, more importantly, forced the Germans to strengthen their garrisons in these previously thought secure posts, tying down forces which could otherwise be sent to active combat fronts. Churchill believed that the enemy should be attacked wherever possible, and SOE was a precision weapon which could be deployed where conventional military forces could not be used. As the SOE was absorbed into the military Special Air Service, Lassen would go on to fight in North Africa, Crete, the Aegean islands, then occupied by Italian and German troops, and mainland Greece. His raid on a German airbase on occupied Crete took out fighters and bombers which could have opposed the Allied landings in Sicily. Later, his small group of raiders, unsupported by any other force, liberated the Greek city of Salonika, bluffing the German commander into believing Lassen's forty raiders and two fishing boats were actually a British corps of thirty thousand men, with armour, artillery, and naval support. After years of raiding in peripheral theatres, Lassen hungered to get into the “big war”, and ended up in Italy, where his irregular form of warfare and disdain for military discipline created friction with his superiors. But he got results, and his unit was tasked with reconnaissance and pathfinding for an Allied crossing of Lake Comacchio (actually, more of a swamp) in Operation Roast in the final days of the war. It was there he was to meet his end, in a fierce engagement against Nazi troops defending the north shore. For this, he posthumously received the Victoria Cross, becoming the only non-Commonwealth citizen so honoured in World War II. It is a cliché to say that a work of history “reads like a thriller”, but in this case it is completely accurate. The description of the raid on the Kastelli airbase on Crete would, if made into a movie, probably cause many viewers to suspect it to be fictionalised, but that's what really happened, based upon after action reports by multiple participants and aerial reconnaissance after the fact. World War II was a global conflict, and while histories often focus on grand battles such as D-day, Stalingrad, Iwo Jima, and the fall of Berlin, there was heroism in obscure places such as the Greek islands which also contributed to the victory, and combatants operating in the shadows behind enemy lines who did their part and often paid the price for the risks they willingly undertook. This is a stirring story of this shadow war, told through the short life of one of its heroes.

Saturday, February 10, 2018

Gnome-o-gram: Experts

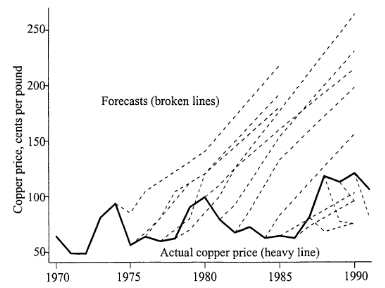

Ever since the 19th century, the largest industry in Zambia has been copper mining, which today accounts for 85% of the country's exports. The economy of the nation and the prosperity of its people rise and fall with the price of copper on the world market, so nothing is so important to industry and government planners as the expectation for the price of this commodity in the future. Since the 1970s, the World Bank has issued regular forecasts for the price of copper and other important commodities, and the government of Zambia and other resource-based economies often base their economic policy upon these pronouncements by high-powered experts with masses of data at their fingertips. Let's see how they've done. The above chart, from a paper [PDF] by Angus Deaton in the Summer 1999 issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives shows, for the years 1970 through 1995, the actual price of copper (solid heavy line) and successive forecasts (light dashed lines) by the august seers of the World Bank. Each forecast departs from the actual price line on the date at which it was issued.

Over a period of a quarter of a century, every forecast by the World Bank has been totally wrong. Further, unlike predictions made by throwing darts while blindfolded, where you'd expect half to be too high and half too low, every single prediction from the 1970s until 1987 erred wildly on the high side, while every one after that date was absurdly pessimistic. You'd have made a much better forecast for the period simply by plotting a random walk between 50 and 100.

And yet people based decisions upon these forecasts, and those in the industry or who depended upon it for their livelihood suffered as a result. Did any of the “experts” who cranked out these predictions suffer or lose their cushy jobs? I doubt it.

In the investment world, firms and forecasters are required to warn potential customers that “past performance is no guarantee of future results”. But in a case like this, past performance is a pretty strong clue that the idiots who turned it in are no more likely to produce usable numbers in the future than a blind monkey firing a shotgun at the chart.

Now, bear in mind what Michael Crichton named the “Murray Gell-Mann Amnesia Effect”:

The above chart, from a paper [PDF] by Angus Deaton in the Summer 1999 issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives shows, for the years 1970 through 1995, the actual price of copper (solid heavy line) and successive forecasts (light dashed lines) by the august seers of the World Bank. Each forecast departs from the actual price line on the date at which it was issued.

Over a period of a quarter of a century, every forecast by the World Bank has been totally wrong. Further, unlike predictions made by throwing darts while blindfolded, where you'd expect half to be too high and half too low, every single prediction from the 1970s until 1987 erred wildly on the high side, while every one after that date was absurdly pessimistic. You'd have made a much better forecast for the period simply by plotting a random walk between 50 and 100.

And yet people based decisions upon these forecasts, and those in the industry or who depended upon it for their livelihood suffered as a result. Did any of the “experts” who cranked out these predictions suffer or lose their cushy jobs? I doubt it.

In the investment world, firms and forecasters are required to warn potential customers that “past performance is no guarantee of future results”. But in a case like this, past performance is a pretty strong clue that the idiots who turned it in are no more likely to produce usable numbers in the future than a blind monkey firing a shotgun at the chart.

Now, bear in mind what Michael Crichton named the “Murray Gell-Mann Amnesia Effect”:

The next time you hear a politician, economist, or other wonk confidently forecast things five or ten years in the future, remember the World Bank and copper prices. Odds are the numbers they're quoting are just as bogus, and they'll pay no price when they're found to be fantasy. Who pays the price? You do.You open the newspaper to an article on some subject you know well. In Murray's case, physics. In mine, show business. You read the article and see the journalist has absolutely no understanding of either the facts or the issues. Often, the article is so wrong it actually presents the story backward—reversing cause and effect. I call these the “wet streets cause rain” stories. Paper's full of them.

In any case, you read with exasperation or amusement the multiple errors in a story, and then turn the page to national or international affairs, and read as if the rest of the newspaper was somehow more accurate about Palestine than the baloney you just read. You turn the page, and forget what you know.

Sunday, February 4, 2018

Reading List: Life 3.0

- Tegmark, Max. Life 3.0. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2017. ISBN 978-1-101-94659-6.

-

The Earth formed from the protoplanetary disc surrounding the

young Sun around 4.6 billion years ago. Around one hundred

million years later, the nascent planet, beginning to solidify,

was clobbered by a giant impactor which ejected the mass that

made the Moon. This impact completely re-liquefied the Earth and

Moon. Around 4.4 billion years ago, liquid water appeared on

the Earth's surface (evidence for this comes from

Hadean

zircons which date from this era).

And, some time thereafter, just about as soon as the Earth

became environmentally hospitable to life (lack of disruption

due to bombardment by comets and asteroids, and a temperature

range in which the chemical reactions of life can proceed),

life appeared. In speaking of the origin of life, the evidence

is subtle and it's hard to be precise. There is completely

unambiguous evidence of life on Earth 3.8 billion years ago, and

more subtle clues that life may have existed as early as 4.28

billion years before the present. In any case, the Earth has

been home to life for most of its existence as a planet.

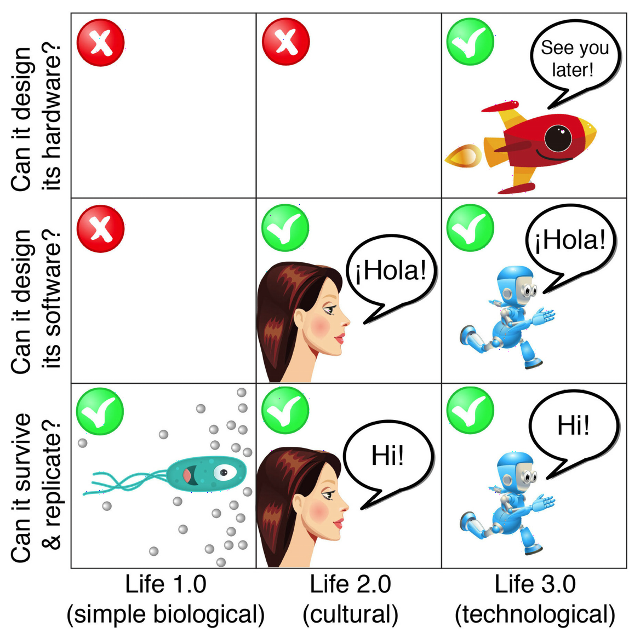

This was what the author calls “Life 1.0”. Initially

composed of single-celled organisms (which, nonetheless, dwarf

in complexity of internal structure and chemistry anything

produced by other natural processes or human technology to this

day), life slowly diversified and organised into colonies of

identical cells, evidence for which can be seen in

rocks

today.

About half a billion years ago, taking advantage of the far more

efficient metabolism permitted by the oxygen-rich atmosphere

produced by the simple organisms which preceded them, complex

multi-cellular creatures sprang into existence in the

“Cambrian

explosion”. These critters manifested all

the body forms found today, and every living being traces

its lineage back to them. But they were still Life 1.0.

What is Life 1.0? Its key characteristics are that it can

metabolise and reproduce, but that it can learn only

through evolution. Life 1.0, from bacteria through insects,

exhibits behaviour which can be quite complex, but that

behaviour can be altered only by the random variation of

mutations in the genetic code and natural selection of

those variants which survive best in their environment. This

process is necessarily slow, but given the vast expanses of

geological time, has sufficed to produce myriad species,

all exquisitely adapted to their ecological niches.

To put this in present-day computer jargon, Life 1.0 is

“hard-wired”: its hardware (body plan and metabolic

pathways) and software (behaviour in response to stimuli) are

completely determined by its genetic code, and can be altered

only through the process of evolution. Nothing an organism

experiences or does can change its genetic programming: the

programming of its descendants depends solely upon its success

or lack thereof in producing viable offspring and the luck of

mutation and recombination in altering the genome they inherit.

Much more recently, Life 2.0 developed. When? If you want

to set a bunch of paleontologists squabbling, simply ask them

when learned behaviour first appeared, but some time between

the appearance of the first mammals and the ancestors of

humans, beings developed the ability to learn from

experience and alter their behaviour accordingly. Although

some would argue simpler creatures (particularly

birds)

may do this, the fundamental hardware which seems to enable

learning is the

neocortex,

which only mammalian brains possess. Modern humans are the

quintessential exemplars of Life 2.0; they not only learn from

experience, they've figured out how to pass what they've learned

to other humans via speech, writing, and more recently, YouTube

comments.

While Life 1.0 has hard-wired hardware and software, Life 2.0 is

able to alter its own software. This is done by training the

brain to respond in novel ways to stimuli. For example, you're

born knowing no human language. In childhood, your brain

automatically acquires the language(s) you hear from those

around you. In adulthood you may, for example, choose to learn

a new language by (tediously) training your brain to understand,

speak, read, and write that language. You have deliberately

altered your own software by reprogramming your brain, just as

you can cause your mobile phone to behave in new ways by

downloading a new application. But your ability to change

yourself is limited to software. You have to work with the

neurons and structure of your brain. You might wish to have

more or better memory, the ability to see more colours (as some

insects do), or run a sprint as fast as the current Olympic

champion, but there is nothing you can do to alter those

biological (hardware) constraints other than hope, over many

generations, that your descendants might evolve those

capabilities. Life 2.0 can design (within limits) its software,

but not its hardware.

The emergence of a new major revision of life is a big

thing. In 4.5 billion years, it has only happened twice,

and each time it has remade the Earth. Many technologists

believe that some time in the next century (and possibly

within the lives of many reading this review) we may see

the emergence of Life 3.0. Life 3.0, or Artificial

General Intelligence (AGI), is machine intelligence,

on whatever technological substrate, which can perform

as well as or better than human beings, all of the

intellectual tasks which they can do. A Life 3.0 AGI

will be better at driving cars, doing scientific research,

composing and performing music, painting pictures,

writing fiction, persuading humans and other AGIs to

adopt its opinions, and every other task including,

most importantly, designing and building ever more capable

AGIs. Life 1.0 was hard-wired; Life 2.0 could alter its

software, but not its hardware; Life 3.0 can alter both

its software and hardware. This may set off an

“intelligence

explosion” of recursive

improvement, since each successive generation of AGIs will be

even better at designing more capable successors, and this cycle

of refinement will not be limited to the glacial timescale of

random evolutionary change, but rather an engineering cycle

which will run at electronic speed. Once the AGI train pulls

out of the station, it may develop from the level of human

intelligence to something as far beyond human cognition as

humans are compared to ants in one human sleep cycle. Here is a

summary of Life 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0.

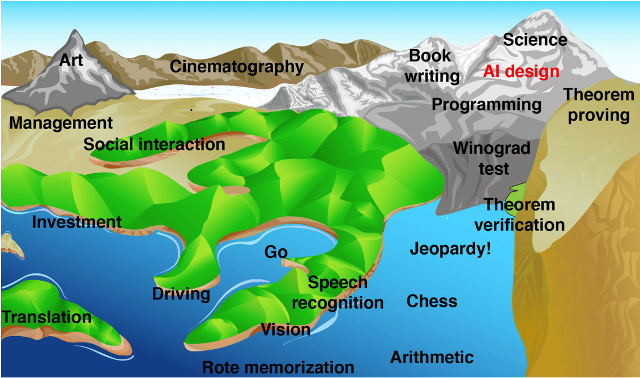

The emergence of Life 3.0 is something about which we, exemplars of Life 2.0, should be concerned. After all, when we build a skyscraper or hydroelectric dam, we don't worry about, or rarely even consider, the multitude of Life 1.0 organisms, from bacteria through ants, which may perish as the result of our actions. Might mature Life 3.0, our descendants just as much as we are descended from Life 1.0, be similarly oblivious to our fate and concerns as it unfolds its incomprehensible plans? As artificial intelligence researcher Eliezer Yudkowsky puts it, “The AI does not hate you, nor does it love you, but you are made out of atoms which it can use for something else.” Or, as Max Tegmark observes here, “[t]he real worry isn't malevolence, but competence”. It's unlikely a super-intelligent AGI would care enough about humans to actively exterminate them, but if its goals don't align with those of humans, it may incidentally wipe them out as it, for example, disassembles the Earth to use its core for other purposes. But isn't this all just science fiction—scary fairy tales by nerds ungrounded in reality? Well, maybe. What is beyond dispute is that for the last century the computing power available at constant cost has doubled about every two years, and this trend shows no evidence of abating in the near future. Well, that's interesting, because depending upon how you estimate the computational capacity of the human brain (a contentious question), most researchers expect digital computers to achieve that capacity within this century, with most estimates falling within the years from 2030 to 2070, assuming the exponential growth in computing power continues (and there is no physical law which appears to prevent it from doing so). My own view of the development of machine intelligence is that of the author in this “intelligence landscape”.

Altitude on the map represents the difficulty of a cognitive task. Some tasks, for example management, may be relatively simple in and of themselves, but founded on prerequisites which are difficult. When I wrote my first computer program half a century ago, this map was almost entirely dry, with the water just beginning to lap into rote memorisation and arithmetic. Now many of the lowlands which people confidently said (often not long ago), “a computer will never…”, are submerged, and the ever-rising waters are reaching the foothills of cognitive tasks which employ many “knowledge workers” who considered themselves safe from the peril of “automation”. On the slope of Mount Science is the base camp of AI Design, which is shown in red since when the water surges into it, it's game over: machines will now be better than humans at improving themselves and designing their more intelligent and capable successors. Will this be game over for humans and, for that matter, biological life on Earth? That depends, and it depends upon decisions we may be making today. Assuming we can create these super-intelligent machines, what will be their goals, and how can we ensure that our machines embody them? Will the machines discard our goals for their own as they become more intelligent and capable? How would bacteria have solved this problem contemplating their distant human descendants? First of all, let's assume we can somehow design our future and constrain the AGIs to implement it. What kind of future will we choose? That's complicated. Here are the alternatives discussed by the author. I've deliberately given just the titles without summaries to stimulate your imagination about their consequences.

- Libertarian utopia

- Benevolent dictator

- Egalitarian utopia

- Gatekeeper

- Protector god

- Enslaved god

- Conquerors

- Descendants

- Zookeeper

- 1984

- Reversion

- Self-destruction

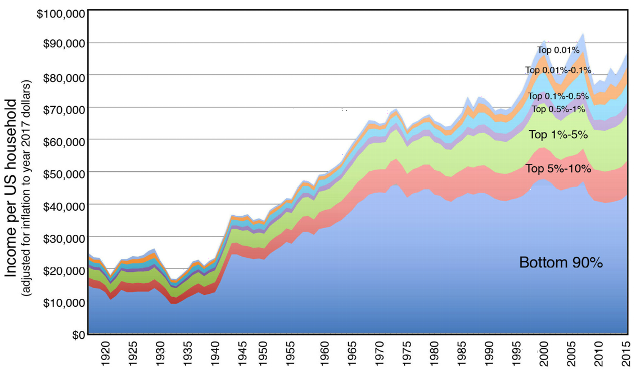

I'm not sure this chart supports the argument that technology has been the principal cause for the stagnation of income among the bottom 90% of households since around 1970. There wasn't any major technological innovation which affected employment that occurred around that time: widespread use of microprocessors and personal computers did not happen until the 1980s when the flattening of the trend was already well underway. However, two public policy innovations in the United States which occurred in the years immediately before 1970 (1, 2) come to mind. You don't have to be an MIT cosmologist to figure out how they torpedoed the rising trend of prosperity for those aspiring to better themselves which had characterised the U.S. since 1940. Nonetheless, what is coming down the track is something far more disruptive than the transition from an agricultural society to industrial production, and it may happen far more rapidly, allowing less time to adapt. We need to really get this right, because everything depends on it. Observation and our understanding of the chemistry underlying the origin of life is compatible with Earth being the only host to life in our galaxy and, possibly, the visible universe. We have no idea whatsoever how our form of life emerged from non-living matter, and it's entirely possible it may have been an event so improbable we'll never understand it and which occurred only once. If this be the case, then what we do in the next few decades matters even more, because everything depends upon us, and what we choose. Will the universe remain dead, or will life burst forth from this most improbable seed to carry the spark born here to ignite life and intelligence throughout the universe? It could go either way. If we do nothing, life on Earth will surely be extinguished: the death of the Sun is certain, and long before that the Earth will be uninhabitable. We may be wiped out by an asteroid or comet strike, by a dictator with his fat finger on a button, or by accident (as Nathaniel Borenstein said, “The most likely way for the world to be destroyed, most experts agree, is by accident. That's where we come in; we're computer professionals. We cause accidents.”). But if we survive these near-term risks, the future is essentially unbounded. Life will spread outward from this spark on Earth, from star to star, galaxy to galaxy, and eventually bring all the visible universe to life. It will be an explosion which dwarfs both its predecessors, the Cambrian and technological. Those who create it will not be like us, but they will be our descendants, and what they achieve will be our destiny. Perhaps they will remember us, and think kindly of those who imagined such things while confined to one little world. It doesn't matter; like the bacteria and ants, we will have done our part. The author is co-founder of the Future of Life Institute which promotes and funds research into artificial intelligence safeguards. He guided the development of the Asilomar AI Principles, which have been endorsed to date by 1273 artificial intelligence and robotics researchers. In the last few years, discussion of the advent of AGI and the existential risks it may pose and potential ways to mitigate them has moved from a fringe topic into the mainstream of those engaged in developing the technologies moving toward that goal. This book is an excellent introduction to the risks and benefits of this possible future for a general audience, and encourages readers to ask themselves the difficult questions about what future they want and how to get there. In the Kindle edition, everything is properly linked. Citations of documents on the Web are live links which may be clicked to display them. There is no index.

Thursday, February 1, 2018

Reading List: Starship Grifters

- Kroese, Robert. Starship Grifters. Seattle: 47North, 2014. ISBN 978-1-4778-1848-0.

- This is the funniest science fiction novel I have read in quite a while. Set in the year 3013, not long after galactic civilisation barely escaped an artificial intelligence apocalypse and banned fully self-aware robots, the story is related by Sasha, one of a small number of Self-Arresting near Sentient Heuristic Androids built to be useful without running the risk of their taking over. SASHA robots are equipped with an impossible-to-defeat watchdog module which causes a hard reboot whenever they are on the verge of having an original thought. The limitation of the design proved a serious handicap, and all of their manufacturers went bankrupt. Our narrator, Sasha, was bought at an auction by the protagonist, Rex Nihilo, for thirty-five credits in a lot of “ASSORTED MACHINE PARTS”. Sasha is Rex's assistant and sidekick. Rex is an adventurer. Sasha says he “never had much of an interest in anything but self-preservation and the accumulation of wealth, the latter taking clear precedence over the former.” Sasha's built in limitations (in addition to the new idea watchdog, she is unable to tell a lie, but if humans should draw incorrect conclusions from incomplete information she provides them, well…) pose problems in Rex's assorted lines of work, most of which seem to involve scams, gambling, and contraband of various kinds. In fact, Rex seems to fit in very well with the universe he inhabits, which appears to be firmly grounded in Walker's Law: “Absent evidence to the contrary, assume everything is a scam”. Evidence appears almost totally absent, and the oppressive tyranny called the Galactic Malarchy, those who supply it, the rebels who oppose it, entrepreneurs like Rex working in the cracks, organised religions and cults, and just about everybody else, appear to be on the make or on the take, looking to grift everybody else for their own account. Cosmologists attribute this to the “Strong Misanthropic Principle, which asserts that the universe exists in order to screw with us.” Rex does his part, although he usually seems to veer between broke and dangerously in debt. Perhaps that's due to his somewhat threadbare talent stack. As Shasha describes him, Rex doesn't have a head for numbers. Nor does he have much of a head for letters, and “Newtonian physics isn't really his strong suit either”. He is, however, occasionally lucky, or so it seems at first. In an absurdly high-stakes card game with weapons merchant Gavin Larviton, reputed to be one of the wealthiest men in the galaxy, Rex manages to win, almost honestly, not only Larviton's personal starship, but an entire planet, Schnufnaasik Six. After barely escaping a raid by Malarchian marines led by the dread and squeaky-voiced Lord Heinous Vlaak, Rex and Sasha set off in the ship Rex has won, the Flagrante Delicto, to survey the planetary prize. It doesn't take Rex long to discover, not surprisingly, that he's been had, and that his financial situation is now far more dire than he'd previously been able to imagine. If any of the bounty hunters now on his trail should collar him, he could spend a near-eternity on the prison planet of Gulagatraz (the names are a delight in themselves). So, it's off the rebel base on the forest moon (which is actually a swamp; the swamp moon is all desert) to try to con the Frente Repugnante (all the other names were taken by rival splinter factions, so they ended up with “Revolting Front”, which was translated to Spanish to appear to Latino planets) into paying for a secret weapon which exists only in Rex's imagination. Thus we embark upon a romp which has a laugh-out-loud line about every other page. This is comic science fiction in the vein of Keith Laumer's Retief stories. As with Laumer, Kroese achieves the perfect balance of laugh lines, plot development, interesting ideas, and recurring gags (there's a planet-destroying weapon called the “plasmatic entropy cannon” which the oft-inebriated Rex refers to variously as the “positronic endoscopy cannon”, “pulmonary embolism cannon”, “ponderosa alopecia cannon”, “propitious elderberry cannon”, and many other ways). There is a huge and satisfying reveal at the end—I kind of expected one was coming, but I'd have never guessed the details. If reading this leaves you with an appetite for more Rex Nihilo, there is a prequel novella, The Chicolini Incident, and a sequel, Aye, Robot. The Kindle edition is free for Kindle Unlimited subscribers.