« September 2006 | Main | November 2006 »

Sunday, October 29, 2006

Reading List: The Jasons

- Finkbeiner, Ann. The Jasons. New York: Viking, 2006. ISBN 0-670-03489-4.

- Shortly after the launch of Sputnik thrust science and technology onto the front lines of the Cold War, a group of Manhattan Project veterans led by John Archibald Wheeler decided that the government needed the very best advice from the very best people to navigate these treacherous times, and that the requisite talent was not to be found within the weapons labs and other government research institutions, but in academia and industry, whence it should be recruited to act as an independent advisory panel. This fit well with the mandate of the recently founded ARPA (now DARPA), which was chartered to pursue “high-risk, high-payoff” projects, and needed sage counsel to minimise the former and maximise the latter. The result was Jason (the name is a reference to Jason of the Argonauts, and is always used in the singular when referring to the group, although the members are collectively called “Jasons”). It is unlikely such a scientific dream team has ever before been assembled to work together on difficult problems. Since its inception in 1960, a total of thirteen known members of Jason have won Nobel prizes before or after joining the group. Members include Eugene Wigner, Charles Townes (inventor of the laser), Hans Bethe (who figured out the nuclear reaction that powers the stars), polymath and quark discoverer Murray Gell-Mann, Freeman Dyson, Val Fitch, Leon Lederman, and more, and more, and more. Unlike advisory panels who attend meetings at the Pentagon for a day or two and draft summary reports, Jason members gather for six weeks in the summer and work together intensively, “actually solving differential equations”, to produce original results, sometimes inventions, for their sponsors. The Jasons always remained independent—while the sponsors would present their problems to them, it was the Jasons who chose what to work on. Over the history of Jason, missile defence and verification of nuclear test bans have been a main theme, but along the way they have invented adaptive optics, which has revolutionised ground-based astronomy, explored technologies for detecting antipersonnel mines, and created, in the Vietnam era, the modern sensor-based “electronic battlefield”. What motivates top-ranked, well-compensated academic scientists to spend their summers in windowless rooms pondering messy questions with troubling moral implications? This is a theme the author returns to again and again in the extensive interviews with Jasons recounted in this book. The answer seems to be something so outré on the modern university campus as to be difficult to vocalise: patriotism, combined with a desire so see that if such things be done, they should be done as wisely as possible.

Saturday, October 28, 2006

Google PageRank Status Add-On for Firefox 2.0

I updated my development machine to Mozilla Firefox 2 a couple of days ago and have had nothing but an excellent experience so far—no crashes, no oddly rendered pages, and seamless transfer of settings from the earlier 1.5.0.7 release. The only downside was that one of my favourite add-ons, Stephane Queraud's Google PageRank extension, was uninstalled by Firefox 2.0 because the latest version posted on mozdev.org, 0.9.6, was deemed not compatible. The PageRank extension is a marvelous little gizmo which appears at the bottom right of the browser window and shows the Google PageRank, from 0 to 10, of the page you're currently viewing. Whatever you think of Google's ranking algorithm, the PageRank they assign has a huge influence on how many people will see a given page in today's Google-dominated search-driven Web, so it's nice to know how influential the page you're viewing is according to the Sultan of Search. Fortunately, for all of us deprived of this information since updating to Firefox 2.0, the author of this handy add-on has posted a 0.9.7 update on his Web site which is compatible with every release of Firefox from 0.9 through 2.0. I installed it yesterday with no problems, and it's great to be able once again have this information available for every page you view.Tuesday, October 24, 2006

Reading List: Islamic Imperialism

- Karsh, Efraim. Islamic Imperialism. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-300-10603-3.

- A great deal of conflict and tragedy might have been avoided in recent years had only this 2006 book been published a few years earlier and read by those contemplating ambitious adventures to remake the political landscape of the Near East and Central Asia. The author, a professor of history at King's College, University of London, traces the repeated attempts, beginning with Muhammad and his immediate successors, to establish a unified civilisation under the principles of Islam, in which the Koranic proscription of conflict among Muslims would guarantee permanent peace. In the century following the Prophet's death in the year 632, Arab armies exploded out of the birthplace of Islam and conquered a vast territory from present-day Iran to Spain, including the entire north African coast. This was the first of a succession of great Islamic empires, which would last until the dismantling of the Ottoman Empire in the aftermath of World War I. But, as this book thoroughly documents, over this entire period, the emphasis was on the word “empire” and not “Islamic”. While the leaders identified themselves as Muslims and exhorted their armies to holy war, the actual empires were very much motivated by a quest for temporal wealth and power, and behaved much as the previous despotisms they supplanted. Since the Arabs had no experience in administering an empire nor a cadre of people trained in those arts, they ended up assimilating the bureaucratic structure and personnel of the Persian empire after conquering it, and much the same happened in the West after the fall of the Byzantine empire. While soldiers might have seen themselves as spreading the word of Islam by the sword, in fact the conquests were mostly about the traditional rationale for empire: booty and tribute. (The Prophet's injunction against raiding other Muslims does appear to have been one motivation for outward-directed conquest, especially in the early years.) Not only was there relatively little aggressive proselytising of Islam, on a number of occasions conversion to Islam by members of dhimmi populations was discouraged or prohibited outright because the imperial treasury depended heavily on the special taxes non-Muslims were required to pay. Nor did these empires resemble the tranquil Dar al-Islam envisaged by the Prophet—in fact, only 24 years would elapse after his death before the Caliph Uthman was assassinated by his rivals, and that would be first of many murders, revolutions, plots, and conflicts between Muslim factions within the empires to come. Nor were the Crusades, seen through contemporary eyes, the cataclysmic clash of civilisations they are frequently described as today. The kingdoms established by the crusaders rapidly became seen as regional powers like any other, and often found themselves in alliance with Muslims against Muslims. Pan-Arabists in modern times who identify their movement with opposition to the hated crusader often fail to note that there was never any unified Arab campaign against the crusaders; when they were finally ejected, it was by the Turks, and their great hero Saladin was, himself, a Kurd. The latter half of the book recounts the modern history of the Near East, from Churchill's invention of Iraq, through Nasser, Khomeini, and the emergence of Islamism and terror networks directed against Israel and the West. What is simultaneously striking and depressing about this long and detailed history of strife, subversion, oppression, and conflict is that you can open it up to almost any page and apart from a few details, it sounds like present-day news reports from the region. Thirteen centuries of history with little or no evidence for indigenous development of individual liberty, self-rule, the rule of law, and religious tolerance does not bode well for idealistic neo-Jacobin schemes to “implant democracy” at the point of a bayonet. (Modern Turkey can be seen as a counter-example, but it is worth observing that Mustafa Kemal explicitly equated modernisation with the importation and adoption of Western values, and simultaneously renounced imperial ambitions. In this, he was alone in the region.) Perhaps the lesson one should draw from this long and tragic narrative is that this unfortunate region of the world, which was a fiercely-contested arena of human conflict thousands of years before Muhammad, has resisted every attempt by every actor, the Prophet included, to pacify it over those long millennia. Rather than commit lives and fortune to yet another foredoomed attempt to “fix the problem”, one might more wisely and modestly seek ways to keep it contained and not aggravate the situation.

Monday, October 23, 2006

Reading List: The Verse by the Side of the Road

- Rowsome, Frank, Jr. The Verse by the Side of the Road. New York: Plume, [1965] 1979. ISBN 0-452-26762-5.

-

In the years before the Interstate Highway System, long

trips on the mostly two-lane roads in the United States could

bore the kids in the back seat near unto death, and drive their

parents to the brink of homicide by the incessant drone of

“Are we there yet?” which began less than half an

hour out of the driveway. A blessed respite from counting

cows, license plate poker, and counting down the dwindling

number of bottles of beer on the wall would be the appearance

on the horizon of a series of six red and white signs, which

all those in the car would strain their eyes to be the first to

read.

WITHIN THIS VALE OF TOIL AND SIN YOUR HEAD GROWS BALD BUT NOT YOUR CHIN—USE

In the fall of 1925, the owners of the virtually unknown Burma-Vita company of Minneapolis came up with a new idea to promote the brushless shaving cream they had invented. Since the product would have particular appeal to travellers who didn't want to pack a wet and messy shaving brush and mug in their valise, what better way to pitch it than with signs along the highways frequented by those potential customers? Thus was born, at first only on a few highways in Minnesota, what was to become an American institution for decades and a fondly remembered piece of Americana, the Burma-Shave signs. As the signs proliferated across the landscape, so did sales; so rapid was the growth of the company in the 1930s that a director of sales said (p. 38), “We never knew that there was a depression.” At the peak the company had more than six million regular customers, who were regularly reminded to purchase the product by almost 7000 sets of signs—around 40,000 individual signs, all across the country. While the first signs were straightforward selling copy, Burma-Shave signs quickly evolved into the characteristic jingles, usually rhyming and full of corny humour and outrageous puns. Rather than hiring an advertising agency, the company ran national contests which paid $100 for the best jingle and regularly received more than 50,000 entries from amateur versifiers. Almost from the start, the company devoted a substantial number of the messages to highway safety; this was not the result of outside pressure from anti-billboard forces as I remember hearing in the 1950s, but based on a belief that it was the right thing to do—and besides, the sixth sign always mentioned the product! The set of signs above is the jingle that most sticks in my memory: it was a favourite of the Burma-Shave founders as well, having been re-run several times since its first appearance in 1933 and chosen by them to be immortalised in the Smithsonian Institution. Another that comes immediately to my mind is the following, from 1960, on the highway safety theme:

THIRTY DAYS HATH SEPTEMBER APRIL JUNE AND THE SPEED OFFENDER

Times change, and with the advent of roaring four-lane freeways, billboard bans or set-back requirements which made sequences of signs unaffordable, the increasing urbanisation of American society, and of course the dominance of television over all other advertising media, by the early 1960s it was clear to the management of Burma-Vita that the road sign campaign was no longer effective. They had already decided to phase it out before they sold the company to Philip Morris in 1963, after which the signs were quickly taken down, depriving the two-lane rural byways of America of some uniquely American wit and wisdom, but who ever drove them any more, since the Interstate went through? The first half of this delightful book tells the story of the origin, heyday, and demise of the Burma-Shave signs, and the balance lists all of the six hundred jingles preserved in the records of the Burma-Vita Company, by year of introduction. This isn't something you'll probably want to read straight through, but it's great to pick up from time to time when you want a chuckle. And then the last sign had been read: all the family exclaimed in unison, “Burma-Shave!”. It had been maybe sixty miles since the last set of signs, and so they'd recall that one and remember other great jingles from earlier trips. Then things would quiet down for a while. “Are we there yet?”

Wednesday, October 18, 2006

Solar System Live Updated

I have just put a new version of Solar System Live into production. This release includes all of the Unix process fork optimisation and security improvements earlier implemented in Earth and Moon Viewer, and upgrades the documentation to use Unicode text elements for opening and closing quotes, dashes, and minus signs. All of the HTML documents remain XHTML 1.0 (Transitional) compliant. As with the update to Earth and Moon Viewer, and the upcoming update to Your Sky, this release should be 100% compatible with existing URLs which reference the Web resource; if you find one that's broken, please whack me upside the head with the Feedback button. I'll be keeping an eye on the Apache error log for the next few days to look for gross pratfalls, but if you spot more subtle goofs I'd very much appreciate your pointing them out. Thanks in advance.Tuesday, October 17, 2006

Heads up! Transit of Mercury on November 8th

Having accomplished my life-long goal of observing a transit of Mercury in 2003 (and then the spectacular transit of Venus a year later), I'd be amiss if I didn't alert readers in the Western Hemisphere and East Asia to the upcoming transit of Mercury on November 8th, 2006. Almost any observer in the Western Hemisphere with a clear sky can see this event (those in Eastern longitudes in the Americas will see the Sun set with the transit in progress, and folks in East Asia will see the Sun rise with the transit already underway—see the summary map for details). Unlike a transit of Venus, which can be glimpsed with the unaided eye through a safe solar filter, in a November transit the disc of Mercury subtends only ten arc seconds: well below the unaided visual acuity of any human. This means that to observe the event, you'll need a telescope with a safe solar filter, since you'll be aiming directly at the Sun to observe the transit. I have had great results with the full aperture solar filters from Orion Telescope and Binoculars, but there are many other vendors with excellent products to choose from. If you miss this event, you'll have to wait until May 9th, 2016 for the next transit of Mercury. Venus will transit the Sun on June 6th, 2012, for the last time until the 11th of December 2117. Immortals with unrestricted space and time travel capability may wish to visit our Quarter Million Year Canon of Solar System Transits to plan their transit-watching excursions in the past and future.Sunday, October 15, 2006

Reading List: Many Worlds in One

- Vilenkin, Alexander. Many Worlds in One. New York: Hill and Wang, 2006. ISBN 0-8090-9523-8.

-

From the dawn of the human species until a time within the

memory of many people younger than I, the origin of the universe

was the subject of myth and a topic, if discussed at all within

the academy, among doctors of divinity, not professors of physics.

The advent of precision cosmology has changed that: the

ultimate questions of origin are not only legitimate areas of

research, but something probed by

satellites in space,

balloons circling the South Pole,

and

mega-projects of

Big Science. The results of these experiments have, in the last

few decades, converged upon a consensus from which few professional

cosmologists would dissent:

Now, this may seem mind-boggling enough, but from these premises, which it must be understood are accepted by most experts who study the origin of the universe, one can deduce some disturbing consequences which seem to be logically unavoidable.- At the largest scale, the geometry of the universe is indistinguishable from Euclidean (flat), and the distribution of matter and energy within it is homogeneous and isotropic.

- The universe evolved from an extremely hot, dense, phase starting about 13.7 billion years ago from our point of observation, which resulted in the abundances of light elements observed today.

- The evidence of this event is imprinted on the cosmic background radiation which can presently be observed in the microwave frequency band. All large-scale structures in the universe grew from gravitational amplification of scale-independent quantum fluctuations in density.

- The flatness, homogeneity, and isotropy of the universe is best explained by a period of inflation shortly after the origin of the universe, which expanded a tiny region of space, smaller than a subatomic particle, to a volume much greater than the presently observable universe.

- Consequently, the universe we can observe today is bounded by a horizon, about forty billion light years away in every direction (greater than the 13.7 billion light years you might expect since the universe has been expanding since its origin), but the universe is much, much larger than what we can see; every year another light year comes into view in every direction.

Let me walk you through it here. We assume the universe is infinite and unbounded, which is the best estimate from precision cosmology. Then, within that universe, there will be an infinite number of observable regions, which we'll call O-regions, each defined by the volume from which an observer at the centre can have received light since the origin of the universe. Now, each O-region has a finite volume, and quantum mechanics tells us that within a finite volume there are a finite number of possible quantum states. This number, although huge (on the order of 1010123 for a region the size of the one we presently inhabit), is not infinite, so consequently, with an infinite number of O-regions, even if quantum mechanics specifies the initial conditions of every O-region completely at random and they evolve randomly with every quantum event thereafter, there are only a finite number of histories they can experience (around 1010150). Which means that, at this moment, in this universe (albeit not within our current observational horizon), invoking nothing as fuzzy, weird, or speculative as the multiple world interpretation of quantum mechanics, there are an infinite number of you reading these words scribbled by an infinite number of me. In the vast majority of our shared universes things continue much the same, but from time to time they d1v3r93 r4ndtx#e~—….

Reset . . . Snap back to universe of origin . . . Reloading initial vacuum parameters . . . Restoring simulation . . . Resuming from checkpoint.

What was that? Nothing, I guess. Still, odd, that blip you feel occasionally. Anyway, here is a completely fascinating book by a physicist and cosmologist who is pioneering the ragged edge of what the hard evidence from the cosmos seems to be telling us about the apparently boundless universe we inhabit. What is remarkable about this model is how generic it is. If you accept the best currently available evidence for the geometry and composition of the universe in the large, and agree with the majority of scientists who study such matters how it came to be that way, then an infinite cosmos filled with observable regions of finite size and consequently limited diversity more or less follows inevitably, however weird it may seem to think of an infinity of yourself experiencing every possible history somewhere. Further, in an infinite universe, there are an infinite number of O-regions which contain every possible history consistent with the laws of quantum mechanics and the symmetries of our spacetime including those in which, as the author noted, perhaps using the phrase for the first time in the august pages of the Physical Review, “Elvis is still alive”. So generic is the prediction, there's no need to assume the correctness of speculative ideas in physics. The author provides a lukewarm endorsement of string theory and the “anthropic landscape” model, but is clear to distinguish its “multiverse” of distinct vacua with different moduli from our infinite universe with (as far as we know) a single, possibly evolving, vacuum state. But string theory could be completely wrong and the deductions from observational cosmology would still stand. For that matter, they are independent of the “eternal inflation” model the book describes in detail, since they rely only upon observables within the horizon of our single “pocket universe”. Although the evolution of the universe from shortly after the end of inflation (the moment we call the “big bang”) seems to be well understood, there are still deep mysteries associated with the moment of origin, and the ultimate fate of the universe remains an enigma. These questions are discussed in detail, and the author makes clear how speculative and tentative any discussion of such matters must be given our present state of knowledge. But we are uniquely fortunate to be living in the first time in all of history when these profound questions upon which humans have mused since antiquity have become topics of observational and experimental science, and a number of experiments now underway and expected in the next few years which bear upon them are described.Curiously, the author consistently uses the word “google” for the number 10100. The correct name for this quantity, coined in 1938 by nine-year-old Milton Sirotta, is “googol”. Edward Kasner, young Milton's uncle, then defined “googolplex” as 1010100. “Google™” is an Internet search engine created by megalomaniac collectivists bent on monetising, without compensation, content created by others. The text is complemented by a number of delightful cartoons reminiscent of those penned by George Gamow, a physicist the author (and this reader) much admires.

Wednesday, October 11, 2006

"Corrupted Downloads": What Is to Be Done?

A couple of months ago I wrote here about truncated downloads with Internet Explorer. First of all, thanks to everybody who responded with their own experiences and information; the response was so overwhelming that I'm afraid that I failed to get back to all of you individually, so let me belatedly express my appreciation now. The reports were enlightening and confirmed, again and again, that Microsoft Internet Explorer is not only prone to truncating long downloads, but, once having done so, stores the incomplete download in its cache and serves subsequent download requests from it, vitiating attempts by persistent users to retry the download. Since I have gotten really, really tired of responding to E-mails from people who report “corrupted” files on my site (often in remarkably abusive language, considering that it's directed at somebody who is providing something for nothing to a global audience), I've now put together a document describing the problem and recommending alternatives to downloading files with Microsoft Internet Explorer. I had originally seized upon FTP, using the command-line FTP client supplied with every copy of Windows since Windows 95, as the last-ditch solution to this problem for users unwilling or unable to migrate to a better browser or install a reliable download utility. This is, of course, torpedoed because Microsoft's FTP client, more than a quarter century after RFC 765, still doesn't support passive mode FTP, and consequently doesn't work for users behind FTP-unaware NAT boxes and firewalls. For those whose network connections allow them to use Microsoft's FTP client, or who install a competently implemented modern replacement, a tutorial on downloading files with FTP walks beginners through the rather gnarly process. Yes, I am aware that the subtitle of this document is a deliberate allusion to Lenin's classic pamphlet, which I cited before, a couple of decades ago, in my assorted scribblings.Monday, October 9, 2006

Curiously Low Yield in Reported North Korean Bomb Test

The United States Geological Survey is now reporting the magnitude of the claimed North Korean nuclear test as 4.2. This seems to be curiously low. Now, estimating explosive yield from the body magnitude of a seismic event is a tricky business, and requires knowledge of details such as the depth of the detonation and the geological properties of the surroundings, but a magnitude around 4.2 is what you'd expect for a detonation of around one kiloton. The “natural size” of a crude fission bomb is in excess of 10 kilotons, from which you'd expect a magnitude closer to 5 (recall that the Richter scale is logarithmic). We'll have to wait for results from the Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Organisation seismic network to refine the yield estimate, but it's worth noting that if the USGS figure of 4.2 is confirmed and no radionuclide release is detected, there is no real evidence that a successful nuclear test was conducted at all. A yield in the low kilotons could simply be the result of blowing up a big pile of high explosive, something which has been done on numerous occasions to calibrate seismic networks, or it's possible the nuclear test resulted in a fizzle yield. It is certainly possible to build nuclear weapons with yields of one kiloton and below—the W-54 warhead of the Davy Crockett nuclear bazooka had a variable yield of only 10 to 20 tons, but that requires a much more difficult to build implosion system to compress a core so much less than a critical mass before detonation, and it is very unlikely that a low kiloton yield device would be used in an initial test. See Fourmilab's on-line Nuclear Bomb Effects Computer for estimates of the effects of surface and airburst detonations with yields between 10 kilotons and 20 megatons.Reading List: Automotive Atrocities

- Peters, Eric. Automotive Atrocities. St. Paul, MN: Motorbooks International, 2004. ISBN 0-7603-1787-9.

- Oh my, oh my, there really were some awful automobiles on the road in the 1970s and 1980s, weren't there? Those born too late to experience them may not be fully able to grasp the bumper to bumper shoddiness of such rolling excrescences as the diesel Chevette, the exploding Pinto, Le Car, the Maserati Biturbo, the Cadillac V-8-6-4 and even worse diesel; bogus hamster-powered muscle cars (“now with a black stripe and fake hood scoop, for only $5000 more!”); the Yugo, the DeLorean, and the Bricklin—remember that one? They're all here, along with many more vehicles which, like so many things of that era, can only elicit in those who didn't live through it, the puzzled response, “What were they thinking?” Hey, I lived through it, and that's what I used to think when blowing past multi-ton wheezing early 80s Thunderbirds (by then, barely disguised Ford Fairmonts) in my 1972 VW bus! Anybody inclined toward automotive Schadenfreude will find this book enormously entertaining, as long as you weren't one of the people who spent your hard-earned, rapidly-inflating greenbacks for one of these regrettable rolling rustbuckets. Unlike many automotive books, this one is well-produced and printed, has few if any typographical errors, and includes many excerpts from the contemporary sales material which recall just how slimy and manipulative were the campaigns used to foist this junk off onto customers who, one suspects, the people selling it referred to in the boardroom as “the rubes”. It is amazing to recall that almost a generation exists whose entire adult experience has been with products which, with relatively rare exceptions, work as advertised, don't break as soon as you take them home, and rapidly improve from year to year. Those of us who remember the 1970s took a while to twig to the fact that things had really changed once the Asian manufacturers raised the quality bar a couple of orders of magnitude above where the U.S. companies thought they had optimised their return. In the interest of full disclosure, I will confess that I once drove a 1966 MGB, but I didn't buy it new! To grasp what awaited the seventies denizen after they parked the disco-mobile and boogied into the house, see Interior Desecrations.

Sunday, October 8, 2006

Fourmilog upgrades to Movable Type 3.33

Despite the crystalline neutronium shield of the Fourmilab firewall, one still worries about security advisories, and so I finally decided to update the content management system used to maintain Fourmilog to version 3.33 of Movable Type. This went more or less as expected, but with the following speed bumps. The configuration file for the new version of Movable Type has removed all of the commented out items for non-default configurations. This may lead you to conclude that Netpbm image processing of thumbnails has been removed. This is not the case; simply copy your ImageDriver NetPBM and NetPBMPath statements into the new configuration file and all will be well (I think; I haven't tried this). Since the Movable Type folks appear to be strongly pushing us toward ImageMagick, I decided to fold and installed the “ImageMagick-perl“ package required to support it. When you install the new release of Movable Type, you will probably also want to create an empty file with the logical name:

/mt-static/user_styles.css

If you don't, you'll see an error message in your HTTP log every time somebody tries to access one of your Movable Type pages.

I couldn't find a suitable “powered by” logo for Movable Type 3.3, so I made my own; it's in the public domain as far as I'm concerned and you're free to use it as you like.

Saturday, October 7, 2006

Animal Magnetism: Pentaspider

As an engineer, I have always admired redundancy: just look at the Fourmilab server farm, firewall, or local network for examples of wretched (but highly reliable) excess in that regard. I was impressed, the evening after a major windstorm that littered the yard and driveway with leaves and branches from nearby trees, to spot this survivor on the wall near the main door to Fourmilab. While eight legs are factory equipment for spiders, he or she (probably she, since there is substantial sexual dimorphism in most spider species, and this was a big 'un) had lost three legs (whether in the recent storm, or in earlier mishaps or combat, there is no way to know), but appeared to be doing just fine.

Spiders appear to be minimally affected by leg loss, although, in males, it may make

them less attractive to arachnochicks. Spiders appear to have a limited ability to regenerate lost limbs, but once they reach adulthood and do not moult into larger and larger exoskeletons, this capacity is lost.

Still, you've got to be impressed by a creature which can lose one more leg than

you started out with and keep on going. I am virtually certain that when we finally tease out the neural wiring, weights, and feedback connections of this very simple control system, there will be multiple whack-the-forehead moments where we say “why didn't I think of that?”, and, if not deemed evidence of intelligent design, at least proof that blind hill-climbing evolution can produce designs which even the most intelligent observer can find extraordinarily difficult to reverse engineer.

I will add this item to the Animal Magnetism page after all of the feedback the commendably critical readers of this chronicle may contribute has been integrated.

I was impressed, the evening after a major windstorm that littered the yard and driveway with leaves and branches from nearby trees, to spot this survivor on the wall near the main door to Fourmilab. While eight legs are factory equipment for spiders, he or she (probably she, since there is substantial sexual dimorphism in most spider species, and this was a big 'un) had lost three legs (whether in the recent storm, or in earlier mishaps or combat, there is no way to know), but appeared to be doing just fine.

Spiders appear to be minimally affected by leg loss, although, in males, it may make

them less attractive to arachnochicks. Spiders appear to have a limited ability to regenerate lost limbs, but once they reach adulthood and do not moult into larger and larger exoskeletons, this capacity is lost.

Still, you've got to be impressed by a creature which can lose one more leg than

you started out with and keep on going. I am virtually certain that when we finally tease out the neural wiring, weights, and feedback connections of this very simple control system, there will be multiple whack-the-forehead moments where we say “why didn't I think of that?”, and, if not deemed evidence of intelligent design, at least proof that blind hill-climbing evolution can produce designs which even the most intelligent observer can find extraordinarily difficult to reverse engineer.

I will add this item to the Animal Magnetism page after all of the feedback the commendably critical readers of this chronicle may contribute has been integrated.

Wednesday, October 4, 2006

Reading List: Artificial Happiness

- Dworkin, Ronald W. Artificial Happiness. New York: Carroll & Graf, 2006. ISBN 0-7867-1714-9.

-

Western societies, with the United States in the lead, appear to be

embarked on a grand scale social engineering experiment with little

consideration of the potentially disastrous consequences both for

individuals and the society at large. Over the last two decades

“minor depression”, often no more than what, in less

clinical nomenclature one would term unhappiness, has become seen

as a medical condition treatable with pharmaceuticals, and

prescription of these medications, mostly by general practitioners,

not psychiatrists or psychologists, has skyrocketed, with drugs such as

Prozac, Paxil, and Zoloft regularly appearing on lists of the most

frequently prescribed. Tens of million of people in the United States

take these pills, which are being prescribed to children and

adolescents as well as adults.

Now, there's no question that these medications have been a Godsend

for individuals suffering from severe clinical depression, which

is now understood in many cases to be an organic disease caused by

imbalances in the metabolism of neurotransmitters in the brain.

But this vast public health experiment in medicating unhappiness

is another thing altogether. Unhappiness, like pain, is a signal

that something's wrong, and a motivator to change things for the

better. But if unhappiness is seen as a disease which

is treated by swallowing pills, this signal is removed, and people

are numbed or stupefied out of taking action to eliminate the

cause of their unhappiness: changing jobs or careers, reducing

stress, escaping from abusive personal relationships, or

embarking on some activity which they find personally rewarding.

Self esteem used to be thought of as something you earned from

accomplishing difficult things; once it becomes a state of mind

you get from a bottle of pills, then what will become of all the

accomplishments the happily medicated no longer feel motivated to

achieve?

These are serious questions, and deserve serious investigation

and a book-length treatment of the contemporary scene and

trends. This is not, however, that book. The author is an

M.D. anæsthesiologist with a Ph.D. in political philosophy

from Johns Hopkins University, and a senior fellow at the

Hudson Institute—impressive credentials. Notwithstanding

them, the present work reads like something written by somebody

who learned Marxism from a comic book. Individuals, entire

professions, and groups as heterogeneous as clergy of

organised religions are portrayed like cardboard cutouts—with

stick figures drawn on them—in crayon. Each group the author

identifies is seen as acting monolithically toward a specific

goal, which is always nefarious in some way, advancing an agenda

based solely on its own interest. The possibility that a family

doctor might prescribe antidepressants for an unhappy patient

in the belief that he or she is solving a problem for the patient

is scarcely considered. No, the doctor is part of a grand conspiracy

of “primary care physicians” advancing an agenda to

usurp the “turf” (a term he uses incessantly) of first

psychiatrists, and finally organised religion.

After reading this entire book, I still can't decide whether the author

is really as stupid as he seems, or simply writes so poorly that he comes

across that way. Each chapter starts out lurching toward a goal,

loses its way and rambles off in various directions until the requisite

number of pages have been filled, and then states a conclusion which

is not justified by the content of the chapter. There are few cliches

in the English language which are not used here—again and again.

Here is an example of one of hundreds of paragraphs to which the only

rational reaction is “Huh?”.

So long as spirituality was an idea, such as believing in God, it fell under religious control. However, if doctors redefined spirituality to mean a sensual phenomenon—a feeling—then doctors would control it, since feelings had long since passed into the medical profession's hands, the best example being unhappiness. Turning spirituality into a feeling would also help doctors square the phenomenon with their own ideology. If spirituality were redefined to mean a feeling rather than an idea, then doctors could group spirituality with all the other feelings, including unhappiness, thereby preserving their ideology's integrity. Spirituality, like unhappiness, would become a problem of neurotransmitters and a subclause of their ideology. (Page 226.)

A reader opening this book is confronted with 293 pages of this. This paragraph appears in chapter nine, “The Last Battle”, which describes the Manichean struggle between doctors and organised religion in the 1990s for the custody of the souls of Americans, ending in a total rout of religion. Oh, you missed that? Me too. Mass medication with psychotropic drugs is a topic which cries out for a statistical examination of its public health dimensions, but Dworkin relates only anecdotes of individuals he has known personally, all of whose minds he seems to be able to read, diagnosing their true motivations which even they don't perceive, and discerning their true destiny in life, which he believes they are failing to follow due to medication for unhappiness. And if things weren't muddled enough, he drags in “alternative medicine” (the modern, polite term for what used to be called “quackery”) and ”obsessive exercise” as other sources of Artificial Happiness (which he capitalises everywhere), which is rather odd since he doesn't believe either works except through the placebo effect. Isn't it just a little bit possible that some of those people working out at the gym are doing so because it makes them feel better and likely to live longer? Dworkin tries to envision the future for the Happy American, decoupled from the traditional trajectory through life by the ability to experience chemically induced happiness at any stage. Here, he seems to simultaneously admire and ridicule the culture of the 1950s, of which his knowledge seems to be drawn from re-runs of Leave it to Beaver. In the conclusion, he modestly proposes a solution to the problem which requires completely restructuring medical education for general practitioners and redefining the mission of all organised religions. At least he doesn't seem to have a problem with self-esteem!

Sunday, October 1, 2006

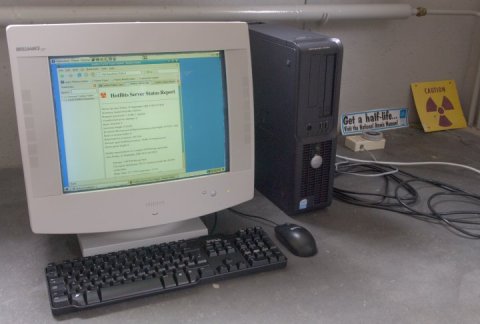

HotBits: Third Generation Server in Production