« Two Pineapple Grenades | Main | Your Sky Updated »

Saturday, January 13, 2007

Reading List: Sister Bernadette's Barking Dog

- Florey, Kitty Burns. Sister Bernadette's Barking Dog. Hoboken, NJ: Melville House, 2006. ISBN 1-933633-10-7.

-

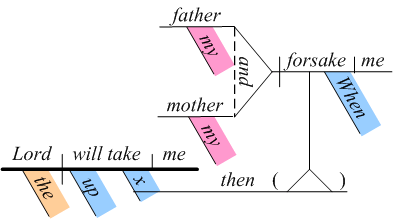

In 1877, Alonzo Reed and and Brainerd Kellogg published Higher

Lessons in English, which introduced their system for the

grammatical diagramming of English sentences. For example, the

sentence “When my father and my mother forsake me, then the Lord

will take me up” (an example from Lesson 63 of their book)

would be diagrammed as:

Diagram by Bruce D. Despain.

Posted at January 13, 2007 22:44