We desire in the first place to record our obligations to General Henry Babbage for the frank and liberal manner in which he has assisted the Committee, not only by placing at their disposal all the information within his reach, but by exhibiting and explaining to them, at no small loss of time and sacrifice of personal convenience, the machinery and papers left by his father, the late Mr. Babbage. Without the valuable aid thus kindly rendered to them by General Babbage it would have been simply impossible for the Committee to have come to any definite conclusions, or to present any useful report.

We refer to the chapter in Mr. Babbage's ‘Passages from the Life of a Philosopher,’ and to General Menabrea's paper, translated and annotated by Lady Lovelace, in the third volume of Taylor's ‘Scientific Memoirs,’ for a general description of the Analytical Engine.

The application of arithmetic to calculating machines differs from ordinary clockwork, and from geometrical construction, in that it is essentially discontinuous. In common clockwork, if two wheels are geared together so as to have a velocity ratio of 10 to 1 (say), when the faster wheel moves through the space of one tooth, the angular space moved through by the slower wheels is one tenth of a tooth. Now in a calculating machine, which is to work with actual figures and to print them, this is exactly what we don't want. We require the second wheel not to move at all until it has to make a complete step, and then we require that step to be taken all at once. The time can be very easily read from the hands of a clock, and so can the gas consumption from an ordinary counter; but a moment's reflection will show what a mess any such machinery would make of an attempt at printing.

This necessity of jumping discontinuously from one figure to another is the fundamental distinction between calculating and numbering machines on the one hand, and millwork or clockwork on the other. A parallel distinction is found in pure mathematics, between the theory of numbers on the one hand, and the doctrine of continuous variation, of which the Differential Calculus is the type, on the other. A calculating machine may exist in either case. The common slide-rule is, in fact, a very powerful calculating machine in which the continuous process is used, and the planimeter is another.

Geometrical construction, being essentially continuous, would be quite out of place in the calculating machine which has to print its results. Linkwork also, for the same reason, is out of place as an auxiliary in any form to the calculation. It may be of service in simplifying the construction of the machine; but it must not enter into the work as an equivalent for arithmetical computation.

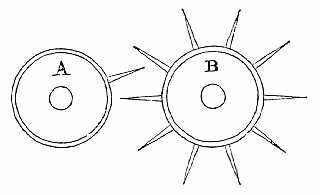

|

| Fig. 1. |

The primary movement of calculating engines is the discontinuous train, of which one form is sketched in the accompanying diagram (fig. 1):—B is the follower, an ordinary spur wheel with (say) 10 teeth; A is its driver, and this has only a single tooth. With a suitable proportion of parts, the single tooth of A only moves B one interval for a whole revolution of A; for it only gears with B by means of this single tooth. When that is not in gear, A simply slips past the teeth of B without moving the latter.

All the other machinery of calculating engines leads up to and makes use of this, or of some transformation of it, as its means of dealing with units of whatever decimal rank, instead of allowing indefinite fractions of units to appear in the result which has to be printed from.

The primary operation of calculation is counting: the secondary

operation is addition, with its counterpart, subtraction. The

addition and subtraction are in reality effected by means of counting,

which still remains the primary operation; but the necessity for

economising labour and time forces upon us devices for performing the

counting processes in a summary manner, and for allowing several of

them to go on simultaneously in the calculating engine. For, if we

use simple counting as our only operation, and suppose our engine set

to 2312 (say), then, in order to add 3245 to it by mere repetition, we

have 3245 unit operations to perform, and this is practically

intolerable. If, however, we can separate the counting, so as to

count on units to units only, tens to tens only, hundreds to hundreds

only, and so forth, we shall only have

turns of the handle, as against 3245 turns. In general terms the number of operations will be measured by the sum of the digits of the number, instead of by the actual number itself. This is exactly analogous to what we should do ourselves in ordinary arithmetic in working an addition sum, if we had not learnt the addition table, but had to count on our fingers in order to add. This statement of the work is, however, incomplete. In the first place the convenience of machinery obliges us to provide 10 steps for each figure, whatever it may be, and there must be an arrangement by which the setting of the figure to be added shall cause a wheel to gain ground by so many steps as the number indicates, and to mark time without gaining ground for the other steps up to 10. Thus, in adding 7 our driver must make a complete turn or 10 steps, equivalent to 1 step of the follower; but only 7 of these steps of the driver must be effective steps, the others being skipped steps. There are various devices for this. One of the simplest and most direct is that used in Thomas's ‘Arithmomètre;’¹ another is the Reducing Bar used by Mr. Babbage.² In the second place, the carrying has to be provided for just as in ordinary addition of numbers. Taking account of all this, it follows that by separating the counting on the whole into counting, on figure by figure, the number of separate steps is reduced from that expressed by the number itself to eleven times the number of its digits; that is to say, for example, the addition of the number 73592 to any other number is reduced from 73592 to 55 steps, and although of this latter some are slipped, there is no gain of time thereby, except in so far as several of the steps may be made simultaneously. The ordinary engines beat the human calculator in respect of adding all the figures simultaneously; but Mr. Babbage was the first to devise a method of performing all the carrying simultaneously too.

Mechanical invention has not yet gone beyond the reduction of the distinct steps involved in the addition of a number consisting of n digits to less than 11n; practically, from the necessity of accompanying the carrying with a warning step, rather more are required.

In all the calculating machines at present known, including Mr. Babbage's analytical engine, multiplication is really effected by repeated addition. It is true that, by a multiplication of parts, more than one addition may be going on simultaneously; but it yet remains true, as a matter of mechanism, that the process is purely one of iterated addition.

By means of reversing wheels or trains, subtraction is as easily and directly performed as addition, and that without becoming in any degree a tentative process. But it is important to observe that the process can be made tentative, so as to give notice when a minuend is, or is about to become, exhausted. This is the necessary preparation for division, which is thus essentially a tentative process. That does not take it out of the power of the machine, because the machine may be, and is, so devised as to accept and act upon the notice. Nevertheless it is a step alieni generis from the direct processes of addition, multiplication, and subtraction. It need hardly be stated that the process of obtaining a quotient consists in counting the number of subtractions employed, up to the machine giving notice of the minuend being exhausted.

Another essentially distinct train is involved in the decimal shift of the unit, in all the four elementary rules. This is most simply and most commonly effected by the sliding of an axis or frame longitudinally, after the manner of a common sliding-scale or rule, so as to bring either the figures, or the teeth which represent them, against those to which their decimal places correspond, and to no others. In multiplication and division, this means a shift for each step of the multiplication and division.

| 1st, | 4 variable cards with the numbers a, b, c, d. |

| 2nd, | an operation card directing the machine to multiply a and b together. |

| 3rd, | a record of the result, namely the product ab = p, as a fifth variable card. |

| 4th, | an operation card directing the addition of p and c. |

| 5th, | a record of the result, namely the sum p+c=q, as a 6th variable card, |

| 6th, | an operation card directing the machine to multiply q and d together. |

| 7th, | a record of the result, namely the product qd=p2, either printed as a final result or punched in a seventh variable card. |

It has already been remarked that the direct work of the engine is a combination and repetition of the processes of addition and subtraction. But in leading up to any given datum by these combinations, there is no difficulty in ascertaining tentatively when this datum is reached, or about to be reached. This is strictly a tentative process, and it appears probable that each such tentamen requires to be specially provided for, so as to be duly noted in the subsequent operations of the machine. There is, however, no necessary restriction to any particular process, such as division; but any direct combination of arithmetic, such as the formation of a polynomial, can be made to lead up to a given value in such a manner as to yield the solution of the corresponding equation. In any such process, however, it is evident that there can be only (to choose a simile from mechanism) one degree of freedom; otherwise the problem would yield a locus, indeterminate alike in common arithmetic, and as regards the capabilities of the machine. The possibility of several roots would be a difficulty of exactly the same character as that which presents itself in Horner's solution of equations, and the same may be said of imaginary roots differing but little from equality. These, however, are extreme cases, with which it is usually possible to deal specially as they arise, and they need not be considered as detracting materially from the value of the engine. Theoretically, the grasp of the engine appears to include the whole synthesis of arithmetic, together with one degree of freedom tentatively. Its capability thus extends to any system of operations or equations which leads to a single numerical result.

It appears to have been primarily designed with the following general object in view—to be coextensive with numerical synthesis and solution, without any special adaptation to a particular class of work, such as we see in the difference engine. It includes that à majori, and it can either calculate any single result, or tabulate any consecutive series of results just as well. But the absence of any speciality of adaptation is one of the leading features of the design.

Mr. Babbage had also considered the indication of the passage through infinity as well as through zero, and also the approach to imaginary roots. For details upon these points we must refer to his ‘Passages from the Life of a Philosopher.’

The only part of the Analytical engine which has yet been put together is a small portion of “the mill,” sufficient to show the methods of addition and subtraction, and of what Mr. Babbage called his “anticipating carriage.” It is understood that General Babbage will (independently of this report) publish a full account of this method. No further mention of it will therefore be made here.

A small portion of the work is in gun-metal wheels and cranks, mounted for the most part on steel shafts. But the greater part of the wheels are in a sort of pewter hardened with zinc. This was adopted from motives of economy. They are for the most part not cast, but moulded by pressure, and the moulds of most of them are in existence.

A large number of drawings of the machinery are also in existence. It is supposed that these are complete to the extent of giving an account of every particular movement essential to the design of the engine; but, for the most part, they are not working drawings, that is to say, they are not drawings suited to be sent straight to the pattern or fitting shop, to be rendered in metal. There are also drawings for the erection of the engine, and there appears to be a complete set of descriptive notes of it in Mr. Babbage's “mechanical notation.” There remains, however, a great deal to be done in the way of calculating quantities and proportions, and in the preparation of working drawings, before any work could actually be set in hand, even if the design be really complete. There is some doubt on this point as the matter stands, and it certainly would be unsafe to rely upon the design being really complete, until the working drawings had been got out. Mechanical engineers are well aware that no complex design can be trusted without this test, at least.

It was Mr. Babbage's rule, in designing mechanism, in the first place to work to his object, in utter disregard of any questions of complexity. This is a good rule in all devising of methods, whether analytical, mechanical, or administrative. But it leaves in doubt, until the design finally leaves the inventor's hands in a finished state, whether it really represents what is meant to be rendered in metal, or whether it is simply a provisional solution, to be afterwards simplified.

It has not been possible for us to form any exact conclusion as to the cost. Nevertheless there are some data in existence which appear to fix a lower limit to the cost. Mr. Babbage, in his published papers, talks of having 1,000 columns of wheels, each containing 50 distinct wheels; this apparently refers to his store. Besides the many thousand moulded pewter wheels for these, and the axes on which they are mounted, there is the mill, also consisting of a series of columns of wheels and of a vast machinery of cams, clutches, and cranks for their control and connection, so as to bring them within the directing power of the Jacquard systems of variable cards and operation cards. Without attempting any exact estimate, we may say that it would surprise us very much if it were found possible to obtain tenders for less than 10,000l., while it would pretty certainly cost a considerable sum to put the design in a fit state for obtaining tenders. On the other hand, it would not surprise us if the cost were to reach three or four times the amount above suggested.

It is understood that towards the close of his life Mr. Babbage had contemplated carrying out the manufacture of the engine on a smaller scale, confining himself to 25 figures instead of 50, and to 200 columns instead of 1000 or more. This would of course reduce the amount of the metal-work proportionately, but we do not think that it would materially reduce the charge which we anticipate for bringing the design into working order.

The questions of strength and durability had by no means escaped Mr. Babbage's attention, and a great deal of his detail bears marks of having been designed with especial reference to these two points. That was essential in a large and complex engine with some thousands of wheels, all requiring at some time or other, although not simultaneously, to be driven by the means of one shaft. This necessarily throws a great deal of pressure, and also a great deal of wear and tear, on the main driving shaft and the gear immediately connected with it. We have no means of knowing, in the present state of the design, to what extent Mr. Babbage had succeeded in reducing this, or whether he had always been successful in arranging his cams and cranks so as to secure the best working angles, and to avoid their being jammed at dead points or otherwise. Giving him full credit for being quite aware of the importance of this, we cannot but doubt whether the design was ever in a sufficiently forward state to enable him, or any one else, to speak with certainty on this point. Several of the existing calculating machines show signs of weakness in the driving-pinions.

One of the movements apparently necessary to the tentative processes of the engine is, when the spur-wheels on a given shaft have been brought into certain definite positions depending on previous operations, to bring up a sharp straight edge against them in a plane passing through the axis of the shaft. This pushes some to right and others to left, according to the position of the crown of the tooth relatively to the straight edge. This operation is necessary to secure that the clearance of the different parts of the machinery, whether originally provided in order to allow it to work smoothly, or whether afterwards increased by working, shall not introduce a numerical error into the result. The principle of this operation is used generally throughout the analytical engine. Its consequent effect, both in respect of the work which it throws upon the main driving gear, and of the wear of the parts which it pushes, forms an important element in considering the durability of the machine. This bar also serves the purpose of locking part of the machine when required.

On the other hand, it is to be remarked, that the use of springs has been wholly discarded by Mr. Babbage, as directors of motion, although he occasionally uses them for return motions.

It has been already remarked that one of the main features of the engine is, that its function is coextensive with numerical synthesis and solution, and that there is an absence of any special adaptation. In thus widening the sphere of its capability, it is made to diverge from the general tendency of mechanical design, which is towards the selection and particularization of the work to be performed, and the restriction of the machinery to one particular cycle of operation, usually within close numerical limits, as well as limited in kind. Nevertheless, modern engineering practice finds ample room for “universal” drills, shaping tools, and other machines having very general adjustments and applications. But it remains practically true that each step of freedom of adjustment is also a step in diminution of special aptitude.

While the analytical engine is capable of turning out a single result, as the combination of a complex series of numbers and operations performed upon them, it can also yield a series of such results in a consecutive form, and thus give tabulated results. Only it is not restricted, as is the difference engine, to the special method of tabulation by finite differences, nor is tabulation its primary function or intention. If its actual capabilities are found to realize the intentions of its inventor, it will tabulate all functions which are within the reach of numerical synthesis, and those direct inversions of it which are known under the name of solutions. It deals, however, with number, and not with analytical form.

Theoretically it might supersede the difference engine, à majori; but for reasons already stated, the specialization of the difference engine would probably give it an advantage over the more powerful engine, when the work was specially suited to finite differences.

There would remain much work, tabular and other, for which differences are not very directly suited. Among these may be mentioned the determination of heavy series of constants and of definite functions of them, such as Bernoulli's numbers, Σx−n, coefficients of various expansions of functions, and inversions of known expansions, solutions of simultaneous equations with large numerical coefficients and many variables, including, as a particular, but important case, the practical correction of observations by the method of least squares. If all sorts of heavy work of this kind could be easily and quickly, as well as certainly, done, by merely selecting or punching a few Jacquard cards and turning a handle, not only much saving of labour would result, but much which is now out of human possibility would be brought within easy reach.

If intelligently directed and saved from wasteful use, such a machine might mark an era in the history of computation, as decided as the introduction of logarithms in the seventeenth century did in trigonometrical and astronomical arithmetic. Care might be required to guard against misuse, especially against the imposition of Sisyphean tasks upon it by influential sciolists. This, however, is no more than has happened in the history of logarithms. Much work has been done with them which could more easily have been done without them, and the old reproach is probably true, that more work has been spent upon making tables than has been saved by their use. Yet, on the whole, there can be no reasonable doubt that the first calculation of logarithmic tables was an expenditure of capital which has repaid itself over and over again. So probably would the analytical engine, whatever its cost, if we could be assured of its success.

Without prejudging the general question referred to us as to the advisability of completing Mr. Babbage's engine in the exact shape in which it exists in the machinery and designs left by its inventor, it is open to consideration whether some modification of it, to the sacrifice of some portion of its generality, would not reduce the cost, and simplify the machinery, so as to bring it within the range of both commercial and mechanical certainty. The “mill,” for example, is an exceedingly good mechanical arrangement for the operations of addition and subtraction, and with a slight modification, with or without store-columns, for multiplication. We have already called attention to the imperfection of the existing machines, which show weakness and occasional uncertainty. It is at least worth consideration whether a portion of the analytical engine might not thus be advantageously specialized, so as to furnish a better multiplying machine than we at present possess. This, we have reason to believe, is a great desideratum both in public and private offices, as well as in aid of mathematical calculators.

Another important desideratum to which the machine might be adapted, without the introduction of any tentative processes (out of which the complications of the machinery chiefly arise) is the solution of simultaneous equations containing many variables. This would include a large part of the calculations involved in the practical application of the method of least squares. The solution of such equations can always be expressed as the quotient of two determinants, and the obtaining this quotient is a final operation, which may be left to the operator to perform by ordinary arithmetic, or which may be the subject of a separate piece of machinery so that the more direct work of forming the determinant, which is a mere combination of the three direct operations of addition, subtraction, and multiplication, may be entirely freed from the tentative process of division, which would thus be prevented from complicating the direct machinery. In the absence of a special engine for the purpose, the solution of large sets of simultaneous equations is a most laborious task, and a very expensive process indeed, when it has to be paid for, in the cases in which the result is imperatively needed. An engine that would do this work at moderate cost would place a new and most valuable computing power at the disposal of analysts and physicists.

Other special modifications of the engine might also find a fair field for reproductive employment. We do not think it necessary to go into these questions at any great length, because they involve a departure, in the way of restriction and specialization, from Mr. Babbage's idea, of which generality was the leading feature. Nevertheless, we think that we should be guilty of an omission, if we were to fail to suggest them for consideration.

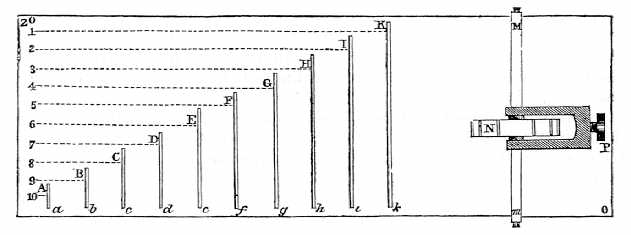

|

| Fig. 2. |

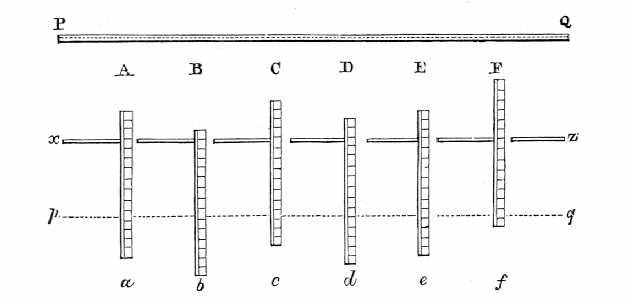

|

| Fig. 3. |