|

|

Information Letter 13 was distributed concurrent with the announcement that I was relinquishing the presidency of Autodesk and turning the office over to Al Green. This letter tried to convey the incremental nature of the transition and to focus people on the challenges that lay ahead.

…we have tried the utmost of our friends, Our legions are brim-full, our cause is ripe: The enemy increaseth every day; We, at the height, are ready to decline. There is a tide in the affairs of men Which taken at the flood leads on to fortune; Omitted, all the voyage of their life Is bound in shallows and miseries. On such a full sea we are now afloat, And we must take the current when it serves, Or lose our ventures.

— Shakespeare, Julius Cæsar, Act IV, Scene 3

What a long, strange trip it's been.

It occurs to me that more than half of the people who work for Autodesk have never had the experience of having one of the these rambling Information Letters plop into their mailbox. For those of you reading your first Information Letter, I'll just say that these Letters were the primary means of communication in the early days when we were trying to get the company together. For the first year, we actually only all got together about once a month, so the Letters served to pass information around economically and force us to put on paper, in specific form, what might be only a mumble in a meeting or on the phone.

It's been a long time since the last Information Letter, and since our recent management reorganisation might leave some people wondering just what is going on around here, I thought I'd put electrons to silicon and bring everybody up to date. Please don't attach any significance to the number Thirteen; that's just the next one in the series.

I've always tried to be open, up-front, and straightforward in these Information Letters. I'll continue that herein. I am not aware of any euphemisms, dissembling, or “cover stories” in any of the material in this Letter. Since some feel moved to weave intricate stories of intrigue around any change that occurs, such protestations may be wasted, but if you've come to believe what I say, believe me when I tell you that this is the straight stuff. The only punches I pull are to honour nondisclosure agreements with manufacturers regarding projects underway, and new product strategy information I don't want to make publicly available.

Back when we were thinking about getting venture capital, I experienced the joy of having strangers walk into a room with me, talk for about a half hour, and then be told by them that I wasn't a “strong CEO” and lacked a “track record” because I hadn't “done it before”. It may be one thing to run a small struggling operation but, they said, entirely another when your sales went to $1 million a month and you had a “real company here”.

I responded that I felt I was entirely competent to run the company up to the ten million dollar a year level, and that after that I thought I was smart enough to know when I began to get out of my depth. I assured them that my ego wouldn't blind me to what was best for the company and I would gladly hand over the company to anybody who could do it better.

In February of 1986 I began to feel that the time might be coming when I should re-examine continuing as president of the company. At the time, I was concerned about whether I had the skills to build the kind of organisation we would need to reach fifty million, then one hundred million, and more in sales. I thought about this long and hard, had numerous conversations with various people in the company, and concluded at the time that I might as well keep on slogging away at it.

Now's where I'm supposed to say that the light shone upon me, and in October I woke up saying, “now is the time”. Well, it didn't happen exactly like that. …Cause what it comes down to is I think I could continue to run the company pretty well for as long as I could stand it before blowing out physically or mentally, but that my being president is not in the best interests of the company. And here's why.

Look, for most of the history of the company, I was spending 8 to 12 hours a day on product development, including programming, talking with others about design issues, meeting with vendors and users, writing manual inserts and ad copy, and so on. I spent the remaining 4 to 8 hours being president. Now for all of that time I was programming I was neglecting the job of president. The president is supposed to be the company's interface to the outside world, representing the company to investors, analysts, giving speeches, and so on, and of course “running the company” on the inside: monitoring progress, watching financials, and planning the development of the organisation. We were very fortunate in having such a large group of founders with such diverse talents, and we were equally fortunate in being able to recruit equally talented and extremely dedicated people in the early days who looked at the work to be done, set to it, and got it done with little or no supervision. So the company required very little explicit “running”, and consequently my concentration on the technical front did not lead to the catastrophe one would expect in the classic Silicon Valley company where only one or two founders have the dream and the rest are working for salary.

I did not come to this odd division of time entirely because I enjoy programming more than being president (though I would be less than candid to say that had nothing to do with it). I did it because I felt that it was in the best interests of the company; a criterion by which I hope I have evaluated every work-related decision I have made in my career. Let me continue with candour, even at the cost of humility. I believe that I am one of the most productive programmers presently living on Planet Earth. I think that in 19 years of programming, I have adequately demonstrated I can go from concept to product in less time than most others, even those considered highly productive, and in conjunction with a small team of others as competent and highly motivated as I, can take on and complete tasks normally measured in calendar years and tens of man years. This is not bragging; it's a statement of what I believe and since it plays a large part in my recent decision, I want to share it with you so you can understand my reasoning.

The very things I consider I do poorly are the things that largely make up the job of president. Worrying about building space, staffing plans, budget versus actuals, day-to-day project status, contract terms, and the like is vitally important—but those are things that I'm not very good at and frankly am not much interested in. They tell me I do a pretty good job at giving speeches, but the tension and effort puts me out of commission for about 4 days before and 1 day after each one—and I don't think that's a good use of what I have to contribute to the company. All of these things were, in the not too distant past, matters one could attend to in less than 10 hours a week, but as the company has grown, they've grown to that horror of horrors, a full time job. And I'm a poor candidate to fill it.

When I decided back in August to spend more time programming and less time “in the office”, it was in part to see how well the company would run with Al Green and Dan Drake filling in for me. It worked superbly. Not only was I able to complete AutoSketch and undertake another project that will be revealed at COMDEX, the overall operation of the company improved (as I expected). In addition, I managed to lose 10 kilograms and not go crazier than usual.

So, the test having succeeded, now's the time to make it official. Now, because doing it before COMDEX will let us explain it in person to our dealers, developers, and users at COMDEX. Now, because by doing it at the end of the fiscal quarter, we can communicate it in our quarterly report to the financial community. Now, because Al Green and Dan Drake have been doing the job for the last four months (and in a large part for the last year or more) and deserve the formal recognition for the job they've excelled at. Now, because the technical and competitive challenges that face us are unprecedented, and we can ill-afford to misapply my talents to administration and speechifying.

You have sat too long here for any good you have been doing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go!

— Oliver Cromwell

All right, all right…I'll come to the point. We have talked for years now about how the rapid advances in computer technology will inevitably bring the power of the mainframe to every person on this globe who seriously wants it. We endured the derision of those who told us “you can't do CAD on a PC”, and now we listen to them explain how they predicted it all along. Every major CAD vendor now competes with us in the PC market, and each now concedes that our core market, 2D drafting, is best served by a PC-based product. As the power of the PC grows, a new challenge faces Autodesk, and we'd better be as far in advance of this trend as we were in 1982 with AutoCAD. In putting AutoCAD on a PC, we were applying our skills as programmers in shoehorning a minicomputer program onto a machine one tenth the size. With the advent of the 68020 and 80386-based workstations this year, the distinction between PCs and mainframes has been erased. Please reread that last sentence two times. If you agree with me that it is true, it has monumental implications for the survival and future of this company.

There is no avoiding war; it can only be postponed to the advantage of others.

— Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince

What it means is that we're moving from a contest of who can cram the most features onto a desktop to a question of who can provide the best tool, period. Most of the constraints of memory, processor speed, secondary storage, and graphics resolution that we assumed in the 1960's and 1970's would hound us until our retirement have been erased by Man's greatest triumph of mass production: photolithography on silicon. The arena now opening and which will probably occupy the next decade is: who can provide the tools which best aid a creative person in turning ideas into reality? I urge you to forget all of that MBA-bullshit about market segmentation, channels of distribution, end-users, value-added, strategic positioning, and the like. I suggest that presuming competent marketing, sales, and distribution, the company that best solves the problems that face designers will end up with the market. Forget PCs versus workstations versus mainframes—that's history. We're building tools, and the tools which work best will endure regardless of the materials of which they're made.

Business-minded decision-makers must learn to invest precious, high-value, near-year dollars to recoup discounted out-year operations and maintenance savings.

— George M. Hess, Colonel, USAF

Right. It comes down to reality. Imagine the concept. What we've been doing for the last four years is building a tool which embodies a language—drawings—which we use to represent reality. This is a language which goes back thousands of years (re-read the Scientific American article about the guide-lines used to build the Parthenon), which represents artifacts in a compact and unambiguous form. AutoCAD is one helluva drawing tool. That's step 1. From here on in it gets harder. When we move from AutoCAD as it exists today to a true 3D AutoCAD, we take the first step on the road to modeling—embodying a physical system in the computer. Once you've encoded a model, you can do many things with it—calculate physical properties, generate part programs to build it, ask “what if” design questions, and so on. I think that every practitioner in the modeling field agrees that the tools we have today are stone axes and bearskins compared to the tools which will evolve over the next ten years. The tools we struggle with today all date from the era of vastly expensive computers with limited memory and poor graphics, and they will be consigned to the sandbox of technology as the new generation of tools appear.

But these tools do not “evolve”. They do not “appear”. They are built by the mental exertions of hardworking men and women, competing in a marketplace that winnows the ill-conceived and inefficient and bestows incalculable rewards upon those who meet the challenge. Autodesk is today a central figure in this competition—what we've done so far has placed us there. The products we develop in the next five years will determine whether we become the force that liberates the minds of designers from the tyranny of calculation and delivers the power tools of modeling from the few to the inventive multitudes, or whether we gather dust in the archives as a footnote in the article on “Design—computers—1980's”.

Spock: He is intelligent but not experienced. His pattern indicates two dimensional thinking.

Kirk: Sulu…translate Z minus ten thousand.

— Star Trek II, The Wrath of Khan

So now we undertake to put, piece by piece, the whole wide world into that little bitty can. We start with a 3D AutoCAD. We add a little thing I've been working on. We labour, patiently and indefatigably, to add the pieces until a designer suddenly discovers a new way of working—a way that's as much an improvement on the old as CAD was over the drawing board or a word processor over retyping pages. I believe in tinkering. I believe in the individual as the source of ideas and inspiration. I believe in providing that individual with tools to explore his or her ideas as powerful as those available to the Pentagon or the Politburo. I believe that the inevitable development of technology will eliminate the advantage of mere size and restore creativity and innovation to the respect due it and paid it through most of the history of this country. I believe that those who make those tools will earn rewards, financial and moral, which will make the wealth generated by Autodesk to date appear insignificant. I believe that Autodesk stands today as the clear leader in the quest to develop these tools.

We shall see how the counsels of prudence and restraint may become the prime agents of mortal danger; how the middle course adopted from desires for safety and a quiet life may be found to lead direct to the bull's eye of disaster.

— Winston Churchill, 1948

Those who know the scope of what I'm talking about may shrink from the magnitude of the job to be done. Creating a realistic picture of a forest at sunset requires more software development than has gone into AutoCAD to date, and more computer time than has been consumed by every AutoCAD user so far, worldwide. Modeling the forces on a tire rolling through a pothole exceeds the capabilities of any existing hardware and software. Increasingly, we will have to build systems of extraordinary complexity which work the first time. Five years ago, Autodesk was a vague idea circulating in my head classified as “new software company”. Our collective efforts will determine, five years from now, whether our progress continues to astound those who assume that competence, commitment, and candour must always be bested by money, management, and marketing.

I am proud of what we've accomplished so far. I am proud of what we're doing. And I'm proud to continue to contribute to our company those things that I do best—full time.

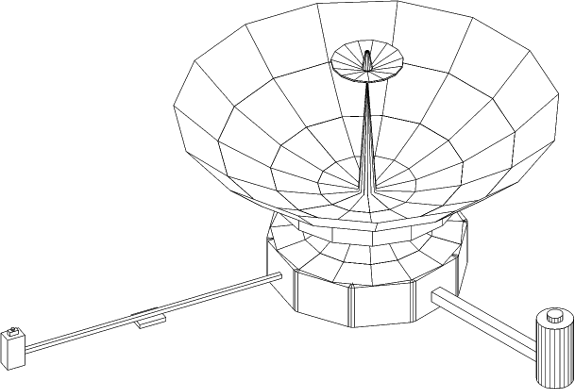

I made the Voyager drawing the night before leaving for COMDEX in 1986 where we were introducing AutoShade. It was based on a picture of Voyager 2 in Scientific American.

|

|