The

Deal

on the Table

After talking to virtually every venture capitalist in the

business, in May of 1984 it appeared that we were finally going

to close a deal. Frank Chambers, who had been introduced to us

by Jack Stuppin, indicated that he was willing to make an

investment in our company. Despite our cynicism, born of endless

tiresome and fruitless meetings which consumed our time when it

was desperately needed to develop the company, we were eager to

obtain funding we could apply to increase our marketing efforts

and seize the market before better-funded competitors entered the

fray.

Mike Ford described the situation as “being in a verdant field

with gold bars lying all around. The question is how many can

we throw in our pickup truck before a big vacuum cleaner comes

down from the sky and sucks them all up.” In essence then,

being greedy and aggressive suckers ourselves, we wanted the cash

to nail down the largest possible market share while we still

could.

After numerous and lengthy discussions, Frank Chambers

communicated the terms of the deal. What follows is a

transcription of Dan Drake's notes taken while hearing the terms

over the phone, with annotations explaining what the terms mean.

Terms I: Frank Chambers

- $500–700K. Size of the investment in dollars. This would

represent about 1/10 of the company.

- $2 preferred, convertible to 1 share common. The investment

would be preferred stock, so that if the company failed the investor

would get his money from the remains before any of the common

shareholders. The stock could be converted to common stock at any

time. This is conventional in venture capital deals.

- If not liquid in 4 1/2 years, we offer to repurchase at

2× price (plus accrued dividends). If the company did not

go public or get acquired, thus providing an opportunity for the

investor to “cash out”, we would buy back the investment at twice

its original value.

- 8% dividend from 2/1/85; with majority of preferred holders or

the board able to substitute change in conversion ratio. We

would pay this dividend from the company's earnings. If we didn't

have the earnings to pay the dividend, the foregone income would be

used to increase the venture capitalist's ownership share of the company.

Most venture capital deals work this way, but it's unusual to have the

dividend start so soon after the deal.

- One demand registration, unlimited piggyback. The investor

could, at will, demand that we make a public offering in order to

enable him to cash out his stock. The company would bear all of the

costs of the public offering. In this, or any other offering the

company made, the investor would be able to sell his shares

“piggyback”, up to the total amount of the shares owned.

- Options.

- 110,000 at $.75.

- Remainder at least $2 + 5% per 6 months.

- Dilution protection, unspecified, above 500,000 options.

- Vesting at least 4 years.

- Forfeited options are canceled, not returned to pool.

- Board of directors. 7 people: preferred elects one, one by

agreement of preferred and common shareholders. Jack Stuppin to be on

the board. Advisory committee to the board

up to 3 people chosen by the investor.

- Representative of preferred investor approves: “All

compensation matters”, and all capital expenditures over $25,000.

- John Walker: key man insurance $500K; employment contract, 2

years, non-competition.

- Frank Chambers approves investors.

- Preferred has first refusal on private equity offerings.

We didn't like it. While many of the terms were conventional and

were what we expected, several totally unexpected constraints on

our ability to develop the company in the way that had brought us

to the present point were contained in the deal. In particular,

our ability to grant stock options to new employees was severely

constrained by limits on the number available, by forcing the

option exercise price to above the price paid by the investor

(who received much better terms on his preferred than the

employee would on his common stock), by retiring from the pool

any options granted to an employee who subsequently left the

company, and by imposing a four-year vesting period on all

options, which the founders of the company felt transformed the

options from their original purpose of allowing employees to

share in the company's success to a kind of twentieth century

indentured servitude which compelled employees to stay with the

company or face forfeiture of their financial gains.

We also thought that the general tone of the deal was far from

consonant with the percentage of the company being

purchased and the demonstrated performance of the company to date

and the track record of its managers. But we still wanted the

cash. So…we came back with the following suggested terms.

Terms II: Us

- $500–700K.

- $2 preferred.

- Repurchase at 1.5× if not liquid in 4 1/2 years;

call on preferred at $4 + 20% per year. The call provision

would allow us to forcibly buy out the investor for twice the

investment plus an increment of 20 percent per year. This was meant

to be symmetrical with the repurchase provision benefiting the

investor.

- 8% dividend from 2/1/85; reduction in conversion price on

missed dividend. This is equivalent to the original requested

terms, just more lucidly put.

- One demand registration if proceeds

exceed $X, X >= $5 million?

- Options: dilution protection by issuing proportional shares at

the same price as exercised options.

Vesting set by board when option issued. No cancellation of

forfeits—return to pool.

- Board of directors. 7 people: preferred elects one, common

elects 6.

- Ceiling on executive salaries and bonuses until some numbers

(sales and profit) achieved; override by preferred representative.

Preferred representative approves capital expenditures over $100,000.

- John Walker: key man insurance; contract, no non-competition.

Being an ornery S.O.B., I said that signing a non-competition

agreement with a company in which I was the largest shareholder was

beneath my dignity and that I wouldn't do it. Moral: don't pick an

asshole to be president of your company.

- Frank Chambers approves investors, but present stockholders can

buy in subject to $ ceiling and regulatory problems. We didn't

want the venture capitalist to be able to veto further investments by

people who got in before he did.

- In general, the constraints have drop-dead provisions. This meant that every constraint on our freedom to run the

company would expire when we reached some well-defined performance

milestones.

He didn't like it. So, we got together and attempted to come up

with another offer which would be acceptable. Here it is.

Terms III: 5/10/84

- $500–700K.

- $2 preferred, convertible.

- Repurchase terms OK (?) We acceded to the original

terms.

- Forced conversion if we get to $10 million (?) annual sales and

$1 million annual profit or make a public stock offering over $5

million.

- One demand registration, piggyback, after 1/1/87 for

>$5 million.

- Options: 100,000 shares at $.75, 200,000 shares at $1.60,

200,000 shares at $2.00, 200,000 shares at $3.00, 200,000

shares at $4.00. Majority of each class of stock to approve

any new plan. Vesting at best 50–25–25 after the first

100,000 shares. This meant that after the first 100,000

shares of options (which were committed to fulfilling options

we'd already granted to people), those who received options

would receive 50% of their shares the first year, 25% the

second year, and 25% the third year. Forfeited options

return to pool.

- Board: ask Chambers*, Ellison, Stuppin. (? Unsettled).

What are the terms on paper?

* If not on board, an advisor.

- $75,000 ceiling on officer and director salaries. Override by 6

or 7 directors.

- $25,000 on capital expenditures. Override how?

- John Walker: key man insurance; employment contract to “devote

substantially all his time”.

- Frank Chambers approves investors. Common holders can buy in

(n.b. might have to keep it intrastate to avoid sophisticated investor

problems). Since people who joined the company in the beginning

and worked themselves to exhaustion to build it to the point that

venture capitalists were interested in investing were not ipso

facto “qualified” to risk their savings by investing

in their own company since they were not already wealthy. This is an

example of what was referred to in the 1980's as the

“opportunity society”.

- First refusal on private equity offerings.

After these terms were presented, it was clear that we would

never come to an agreement on the issue of awarding stock options

to employees to give them a real stake in the company's success.

In addition, the overall flavour of the deal seemed to us totally

inappropriate for a company which was, at the time of these

negotiations, generating sales equal to the size of the deal

every month and generating after-tax profits close to the size

of the deal every quarter.

We couldn't believe that this was the best deal obtainable for

venture funding of the company, and we were inclined to ask

around to see if this was reasonable. But, our Distinguished

Financial Advisor informed us that this would constitute

“shopping the deal” when “a deal was on the

table” which was right out by the genteel standards of the

venture community, and that he could not countenance such

unrefined behaviour (notwithstanding the fact that in the real

world this kind of collusion is called “conspiracy in

restraint of trade” and people go to jail for it).

So, after a brief weekend meeting in which we discovered we all

agreed on the obvious conclusion, we decided to graciously

decline this generous offer of funding and carry on with our own

resources. Upon hearing this decision, Jack Stuppin said that if

we didn't take this deal, he did not wish to be a shareholder and

wanted us to buy him out. Not wishing to deplete our treasury,

we declined. In not accepting our terms, which differed from his

original proposal primarily in issues of philosophy, not money,

Frank Chambers chose to forgo an investment of $500,000 which, if

held until the stock price hit its 1987 high, would have

appreciated to more than $37 million.

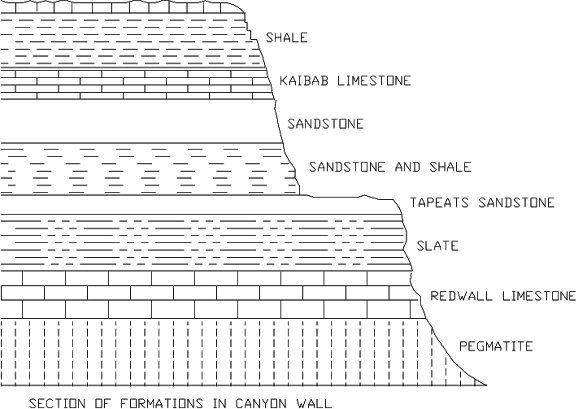

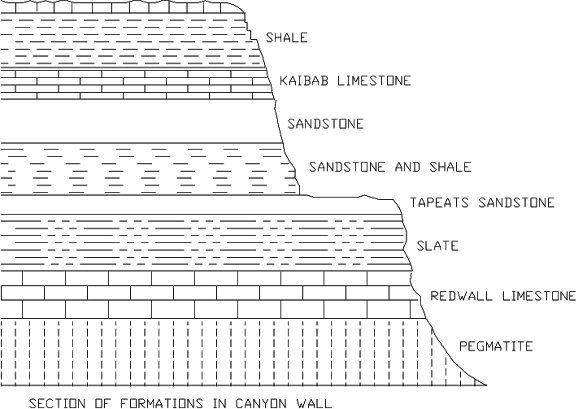

Peter

Barnett drew this geological strata illustration in 1984 to

demonstrate the multiple dot and dash line types introduced in

AutoCAD 2.0. The drawing doesn't represent any real geological

formation—it was made up out of thin air, not hard rock. It

has been used as a sample drawing from AutoCAD 2.0 to date.