« Mozilla Thunderbird "Domain Name Mismatch": Explanation and Work-Around | Main | Reading List: Theo Gray's Mad Science »

Thursday, August 27, 2009

Gnome-o-gram: Adjustable Rate Mortgages, Notional Value, and the Double Dip

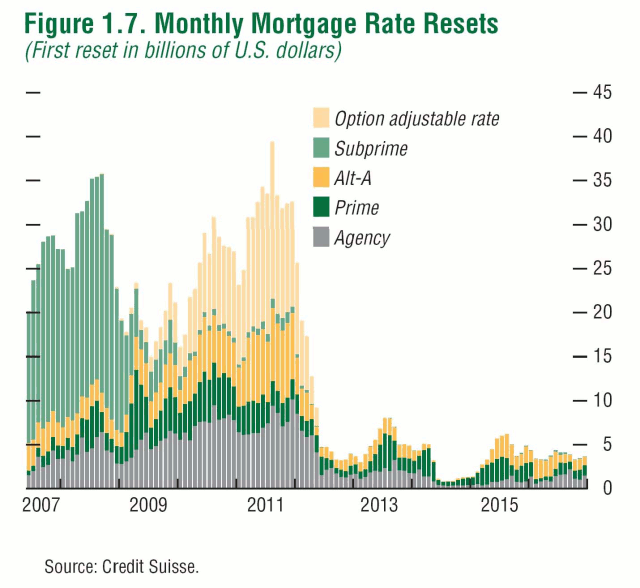

Financial markets have recovered since their March 2009 lows, and the sense of crisis and impending doom seems to have abated somewhat, although many worry about the ultimate consequences of the enormous injections of debt-financed liquidity done by the U.S. government, and forecasts for deficits and accumulation of debt which are unprecedented in the human experience. So, is it time to let out a sigh of relief, think about getting back into the markets, and devote less time and resources to planning for a worst case scenario? I don't think so; here's why. You'll recall that the proximate cause of the current financial crisis was the meltdown of “subprime” adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs) the borrowers could not possibly afford to pay when their initially low-ball interest rates “reset” to market rates. Borrowers who took out these loans were betting that by the time the loan reset, the value of the house would have appreciated sufficiently so that they'd have enough positive equity to qualify for a loan with more affordable terms with which they'd refinance and retire the ARM. This worked out just fine as long as the real estate bubble continued to inflate (indeed, along with other ill-considered policies encouraged by the U.S. government, it was one of the main reasons for the residential real estate bubble in the first place). Once property values began to level off and started to fall, however, these ARMs were a disaster. A “homeowner” with a loan for more than the property is worth isn't going to be able to refinance, and not being able to make the monthly payments once the interest resets, will have no option but to default and allow the property to be foreclosed. Even if the borrower is able to make the payments, there's still a strong incentive to default anyway rather than pay on a loan that's worth more than the house. There's even a name for ARM borrowers mailing the keys to the house back to the bank: “jingle mail”. The second factor which contributed to the crisis was that these mortgages were not, as in times of old, held by the bank that issued them as assets and serviced by the bank, but rather packaged up with many other mortgages and immediately resold as “mortgage-backed securities”, often of bewildering complexity, involving over-the-counter (OTC) financial derivative contracts which combined aspects of insurance, options, and futures. The mortgage-backed securities, in turn, were sold to financial institutions all around the world, which treated them, even if based upon what amounted to junk mortgages, as highly-rated debt instruments on the basis of the insurance against default provided by the derivative contracts (especially “credit default swaps”). Now you can see how the smash-up happened. The subprime ARMs, as a class, were headed to default. This violated the fundamental assumption of insurance: that pooling individual risks reduces the risks in the aggregate. When an entire asset category melts down, however, it's like an insurance company which has written homeowner policies on hundreds of thousands of houses in a city, and then an earthquake levels the entire city. In this case, the issuers of these contracts, including AIG, were liable to investors when the mortgages underlying the securities defaulted, and would have been unable to pay the claims. This, then, would have required a drastic (and almost impossible to calculate) mark-down of the value of the mortgage-backed securities, whose collapse in value may have rendered the financial institutions that owned them insolvent, setting off a chain-reaction collapse on a global scale. The principal reason for the AIG bailout was to keep this “counterparty risk” from setting the whole cataclysm into motion. Well, here we are coming up on a year after the wheels almost came off the global financial system in September 2008, and after the bailouts, nationalisations, forced mergers, “stimulus” packages and abundant grandstanding and demagoguery by politicians, the system is still up and running, albeit with a weak economy and increasing unemployment. So, is the worst behind us? Don't count on it. Take a look at the following chart. Note that now we're almost exactly in the trough between the end of the massive resets of subprime ARMs which precipitated the original crisis, and a rapidly approaching wave of resets of other kinds of ARMs which became popular in the wake of the subprime collapse. Note that only the dark green portion of this chart represents “prime” ARMs—everything else is lower in quality. (This chart does not show fixed-rate mortgages—only a small fraction of borrowers who meet prime credit standards opt for ARMs.) Look at the size of the “Option adjustable rate” bulge coming up. These are loans where the borrower can adjust their monthly payment, and in some cases make a payment so small that their equity actually falls. So, starting in around May 2010, and running through October 2011, we have a second wave of ARM resets which is just about as large as the subprime bulge which got us into this mess.

However, the last time we went through an ARM reset we were near the top of the real estate bubble. The next time, unless there's a rapid and dramatic recovery in the residential property market (which is not the way to bet), many of the borrowers in the next wave of resets will be “under water”: their loans are substantially larger than the current resale value of their houses, and therefore have an even greater incentive to go the jingle mail route.

Now let's take a look at how successful financial institutions have been in winding down that mountain of opaque derivative contracts on their books. According to the most recent semiannual OTC derivatives statistics issued

by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the total over-the-counter derivatives outstanding (PDF) were, in notional value, US$595 trillion in December 2007, 684 trillion in June 2008, and down to 591 trillion by December 2008. (There are no more recent figures available from the BIS.) So, the derivatives appear to be winding down, but there's a heck of a way to go!

If your head is about to explode trying to get your mind around the concept of US$600 trillion (here's a sense of what a hundredth of that looks like), let me say a few words about the “notional value” of a derivatives contract. Let's consider a very simple financial derivative, the wheat futures contract discussed earlier. Each contract is for the delivery of 5,000 bushels of wheat, and is priced in cents per bushel. The notional value of the contract is that of the underlying asset: the wheat. This contract is currently trading at around US$4.75, so the notional value of the contract is US$23,750. But to buy or sell such a contract, you only have to put up the margin, which is currently just US$2,700, and to maintain the contract you have to maintain a margin of US$2,000. If the trade goes against you and your margin falls below US$2,000 you have to either put up more margin money or be sold out of the contract at a loss. So in this case, while the full value of the asset that underlies the contract is US$23,750, the actual investment at risk is on the order of 10% of this figure. It is this leverage which makes futures markets so exciting (and risky) to trade.

It is, of course, possible to imagine a situation in which you could lose the entire notional value of a derivatives contract. If you bought a wheat contract and, for some reason, the price of wheat went to zero overnight, you'd be on the hook for the entire value of the contract. But there's no plausible scenario in which that could happen, and since exchange-traded futures contracts are settled every day at the close of the market, actual day-to-day fluctuations are of modest size. For an over-the-counter derivative transaction, however, the actual valuation usually only happens at the expiration date, and given the complexity of many of these contracts, it can be extremely difficult to place a value on them (or, in the term of art, “mark to market”) prior to the settlement date. Further, it is entirely plausible that, say, an insurance contract covering a pool of subprime ARMs could go all the way to the full principal value of the mortgages (or something close to it) if that entire class of asset implodes, as more or less happened in recent months. This means that for many kinds of derivatives, while calculating the notional value is simple, estimating the market value of the risk to the counterparties involves subtleties and a great deal of judgement. The BIS goes ahead and tries anyway (in large part relying upon those who report data to them), and shows gross market values of outstanding OTC derivatives as US$16 trillion in December 2007, 20 trillion in June 2008, and 34 trillion in December 2008. So (to the extent you trust these figures), while the notional value has peaked and is going down, the market value (the estimation of the risk to the parties of the contract) has increased steadily over time. It's tempting to attribute this to a rising risk premium for these instruments, but it's difficult to draw conclusions from numbers which aggregate a multitude of very different securities.

In conclusion, it looks like that in 2010 and 2011 the financial system may face a shock due to defaults on ARMs comparable in size to that of 2007–2008, and the total magnitude of outstanding derivative contracts (mortgage-based and other) remains enormous, whether measured by notional value (which obviously overstates the risk, but by how much?) or estimated market value (which depends upon many assumptions of dubious merit, especially in a crisis). The possibility of a house of cards collapse is still very much on the table, and should one begin, the flexibility of governments to avert it will have been reduced by the enormous debt they've run up trying to paper over the first wave of the collapse. The prudent investor, while earnestly hoping nothing like this comes to pass, should bear in mind that it may, and take appropriate precautions.

Note that now we're almost exactly in the trough between the end of the massive resets of subprime ARMs which precipitated the original crisis, and a rapidly approaching wave of resets of other kinds of ARMs which became popular in the wake of the subprime collapse. Note that only the dark green portion of this chart represents “prime” ARMs—everything else is lower in quality. (This chart does not show fixed-rate mortgages—only a small fraction of borrowers who meet prime credit standards opt for ARMs.) Look at the size of the “Option adjustable rate” bulge coming up. These are loans where the borrower can adjust their monthly payment, and in some cases make a payment so small that their equity actually falls. So, starting in around May 2010, and running through October 2011, we have a second wave of ARM resets which is just about as large as the subprime bulge which got us into this mess.

However, the last time we went through an ARM reset we were near the top of the real estate bubble. The next time, unless there's a rapid and dramatic recovery in the residential property market (which is not the way to bet), many of the borrowers in the next wave of resets will be “under water”: their loans are substantially larger than the current resale value of their houses, and therefore have an even greater incentive to go the jingle mail route.

Now let's take a look at how successful financial institutions have been in winding down that mountain of opaque derivative contracts on their books. According to the most recent semiannual OTC derivatives statistics issued

by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the total over-the-counter derivatives outstanding (PDF) were, in notional value, US$595 trillion in December 2007, 684 trillion in June 2008, and down to 591 trillion by December 2008. (There are no more recent figures available from the BIS.) So, the derivatives appear to be winding down, but there's a heck of a way to go!

If your head is about to explode trying to get your mind around the concept of US$600 trillion (here's a sense of what a hundredth of that looks like), let me say a few words about the “notional value” of a derivatives contract. Let's consider a very simple financial derivative, the wheat futures contract discussed earlier. Each contract is for the delivery of 5,000 bushels of wheat, and is priced in cents per bushel. The notional value of the contract is that of the underlying asset: the wheat. This contract is currently trading at around US$4.75, so the notional value of the contract is US$23,750. But to buy or sell such a contract, you only have to put up the margin, which is currently just US$2,700, and to maintain the contract you have to maintain a margin of US$2,000. If the trade goes against you and your margin falls below US$2,000 you have to either put up more margin money or be sold out of the contract at a loss. So in this case, while the full value of the asset that underlies the contract is US$23,750, the actual investment at risk is on the order of 10% of this figure. It is this leverage which makes futures markets so exciting (and risky) to trade.

It is, of course, possible to imagine a situation in which you could lose the entire notional value of a derivatives contract. If you bought a wheat contract and, for some reason, the price of wheat went to zero overnight, you'd be on the hook for the entire value of the contract. But there's no plausible scenario in which that could happen, and since exchange-traded futures contracts are settled every day at the close of the market, actual day-to-day fluctuations are of modest size. For an over-the-counter derivative transaction, however, the actual valuation usually only happens at the expiration date, and given the complexity of many of these contracts, it can be extremely difficult to place a value on them (or, in the term of art, “mark to market”) prior to the settlement date. Further, it is entirely plausible that, say, an insurance contract covering a pool of subprime ARMs could go all the way to the full principal value of the mortgages (or something close to it) if that entire class of asset implodes, as more or less happened in recent months. This means that for many kinds of derivatives, while calculating the notional value is simple, estimating the market value of the risk to the counterparties involves subtleties and a great deal of judgement. The BIS goes ahead and tries anyway (in large part relying upon those who report data to them), and shows gross market values of outstanding OTC derivatives as US$16 trillion in December 2007, 20 trillion in June 2008, and 34 trillion in December 2008. So (to the extent you trust these figures), while the notional value has peaked and is going down, the market value (the estimation of the risk to the parties of the contract) has increased steadily over time. It's tempting to attribute this to a rising risk premium for these instruments, but it's difficult to draw conclusions from numbers which aggregate a multitude of very different securities.

In conclusion, it looks like that in 2010 and 2011 the financial system may face a shock due to defaults on ARMs comparable in size to that of 2007–2008, and the total magnitude of outstanding derivative contracts (mortgage-based and other) remains enormous, whether measured by notional value (which obviously overstates the risk, but by how much?) or estimated market value (which depends upon many assumptions of dubious merit, especially in a crisis). The possibility of a house of cards collapse is still very much on the table, and should one begin, the flexibility of governments to avert it will have been reduced by the enormous debt they've run up trying to paper over the first wave of the collapse. The prudent investor, while earnestly hoping nothing like this comes to pass, should bear in mind that it may, and take appropriate precautions.

Posted at August 27, 2009 20:06