Ten years have elapsed since a committee of the British Association reported upon the Analytical Engine of my father, Charles Babbage, and I desire now, while offering a few remarks upon that Report, to endeavour to convey some idea of the mechanical arrangements of the engine to those who may be interested in it.

2. I am well assured that a time will come when such an engine will be completed and be a powerful means of enlarging not only pure mathematical science, but other branches of knowledge, and I wish, as far as in me lies, to hasten that time, and to help towards the general appreciation of the labours of my father, so little known or understood by the multitude even of the educated.

3. He considered the Paper by Menabrea, translated with notes by Lady Lovelace, published in volume 3 of Taylor's “Scientific Memoirs,” as quite disposing of the mathematical aspect of the invention. My business now is not with that.

4. The idea of the Analytical Engine arose thus: When the fragment of the Difference Engine, now in the South Kensington Museum, was put together early in 1833, it was found that, as had been before anticipated, it possessed powers beyond those for which it was intended, and some of them could be and were demonstrated on that fragment.

5. It was evident that by interposing a few connecting-wheels, the column of Result can be made to influence the last Difference, or other part of the machine in several ways. Following out this train of thought, he first proposed to arrange the axes of the Difference Engine circularly, so that the Result column should be near that of the last Difference, and thus easily within reach of it. He called this arrangement “the engine eating its own tail.” But this soon led to the idea of controlling the machine by entirely independent means, and making it perform not only Addition, but all the processes of arithmetic at will in any order and as many times as might be required. Work on the Difference Engine was stopped on 10th April, 1833 and the first drawing of the Analytical Engine is dated in September, 1834.

6. The object may shortly be given thus: It is a machine to calculate the numerical value or values of any formula or function of which the mathematician can indicate the method of solution. It is to perform the ordinary rules of arithmetic in any order as previously settled by the mathematician, and any number of times and on any quantities.

7. It is to be absolutely automatic, the slave of the mathematician carrying out his orders and relieving him from the drudgery of computing.

8. The Analytical Engine is of course to print the results, or any intermediate result arrived at. He regarded this as an indispensable requisite, without which a calculating machine might indeed be useful for some purposes, but not for those of any scientific value. The perpetual risk of error in copying and transferring lines of figures is most troublesome, and tends to make results, themselves perfectly accurate, unreliable in use.

9. It is at once seen that the necessity of the engine being automatic imposes a gigantic task on the inventor. The first means employed to meet it is the use of cards to govern the engine. These are very similar to those in use in the Jacquard loom, to which we owe the figured patterns in the beautiful fabrics we see everywhere in common use.

10. One set of cards would be used to communicate the “given numbers,” or constants of a problem to the machine. I shall call these throughout this paper “Number Cards.”

11. Another set of cards would be used to direct to which particular place or column in the engine these numbers, or any intermediate numbers arising in the course of the calculation, are to be conveyed or transferred; these cards I will call “Directive Cards” There would also be other “Directive Cards” for general purposes of control when necessary.

12. A third sort, called “Operation Cards,” would direct the actual operations to be performed, these would put the engine mechanically into a condition to perform the particular operation required—Addition, Subtraction, &c., &c.

13. I was once asked, “How do you set the question? Do you write it on paper and put it into the machine?” Well, given the problem, the mathematician must first of all settle the operations and the particular quantities each is to be performed on and the time for each operation.

14. Then the superintendent of the engine must make a “Number Card” for each “given number,” and settle the particular column in the machine on to which each “given number” is to be first received, and assign columns for every intermediate result expected to arise in the course of the calculation

15. He will then prepare “Directive Cards” accordingly, and these, together with the necessary “Operation Cards” being placed in the engine, the question will have been set; not exactly, as my friend suggested, written on paper, but in cardboard, and motion being supplied the engine will give the answer.

16. Now this appears a long process for what may be a simple question, but it is to be noted that the engine is designed for analytical purposes, and it would be like using the steam hammer to crush the nut, to use the Analytical Engine to solve common sums in arithmetic; or, adopting the language of Leibnitz: “It is not made for those who sell vegetables or little fishes, but for observatories, or the private rooms of calculators, or for others who can easily bear the expense, and need a good deal of calculation.” Moreover, except the “Number Cards,” all the cards, once made for any given problem, can be used for the same problem, with any other “given numbers,” and it would not be necessary to prepare them a second time—they could be carefully kept for future use. Each formula would require its own set of cards, and by degrees the engine would have a library of its own.

17. Thus the values for any number of Life Insurance Policies might be calculated one after the other by merely supplying fresh cards for the age, amount, rate of interest, &c., for each individual case.

18. The separation of “Operation Cards” from the numbers to be operated on is complete. The powers of the engine are the most extended, but each set of cards makes it special for the solution of one particular problem; each individual case of which, again, requires its own “Number Cards.”

19. Taking the formula used by Mr. Merrifield (ab + c)d as an illustration, the full detail of the cards of all sorts required, and the order in which they would come into play is this:—

The four cards for the “given numbers” a, b, c and d, strung together are placed by hand on the roller, these numbers have to be placed on the columns assigned to them in a part of the machine called “The Store,” where every quantity is first received and kept ready for use as wanted.

| Directive Card |

Operation Card |

|

|---|---|---|

| 1st | … | Places a on column 1 of Store |

| 2nd | … | Places b on column 2 of Store |

| 3rd | … | Places c on column 3 of Store |

| 4th | … | Places d on column 4 of Store |

| 5th | … | Brings a from Store to Mill |

| 6th | … | Brings b from Store to Mill |

| … | 1 | Multiplies a and b=p |

| 7th | … | Takes p to column 5 of Store where it is kept for use and record |

| 8th | … | Brings p into Mill |

| 9th | … | Brings c into Mill |

| … | 2 | Adds p and c=q |

| 10th | … | Takes q to column 6 of Store |

| 11th | … | Brings d into Mill |

| 12th | … | Brings q into Mill |

| … | 3 | Multiplies d×q=p2 |

| 13th | … | Takes p2 to column 7 of Store |

| 14th | … | Takes p2 to printing or stereo-moulding apparatus |

20. We have thus besides the “Given Number” Cards, three “Operation Cards” used, and fourteen “Directive Cards;” each set of cards would be strung together and placed on a roller or prism of its own; this roller would be suspended and be moved to and fro. Each backward motion would cause the prism to move one face bringing the next card into play, just as on the loom

21. It is obvious that the rollers must be made to work in harmony, and for this purpose the levers which make the rollers turn would themselves be controlled by suitable means, or by general “Directive Cards,” and the beats of the suspended rollers be stopped in the proper intervals.

22. This brings me to the second great distinguishing feature of the engine, the principle of “Chain.” This enables us to deal mechanically with any single combination which may occur out of many possible, and thus to be ready for any or every contingency which may arise.

23. Supposing that it is desired to provide for a certain possible combination such as, for example, the concurrence of ten different events, it could be effected mechanically thus—each event would be represented by an arm turning on its axis, and having at its end a block held loosely and capable of vertical motion independently of the arm which carries it. Now suppose each of these arms to be brought, on the occurrence of the event it represents, into a position so that the blocks should all be in one vertical line, then if the block in the lowest arm was raised by a lever, it would raise all the nine blocks together, and the top one could be made to ring a bell or communicate motion, &c. &c.; but if any one of the ten events had not happened, its block would be out of the “Chain,” and the lowest block would be raised in vain and the bell remain silent.

24. This is the simplest form of “Chain,” there may be many modifications of it to suit various purposes.

25. In its largest extent it will appear in the Anticipating Carriage further on, but in its simplest form it appears here as a means of producing intermittent motion at uncertain intervals, which may or may not be previously known either to the mathematician or even to the superintendent of the engine who had prepared the cards.

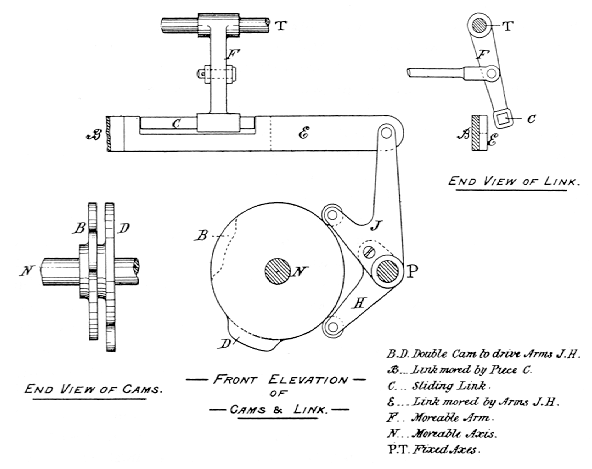

26. In our illustration the first operation card happens to be multiplication, and the time this would occupy necessarily depends upon the number of digits in the two quantities multiplied. Now when multiplication is directed, the “Chain” to every part of the machine not wanted will be broken, and all motion thus stopped till the multiplication is completed, and whenever the last step of that is reached, the “Chain” will be restored.

27. The Chain for this purpose may be made this way, a link is cut and the two ends are brought side by side, overlapping each other; a part of each link is then cut away exactly the same in both pieces. Now if the piece in communication with the driving power is moved, the other is not, and remains stationary; but if a block is let fall into the space cut away so as to fill the gaps in both parts of the severed link, the chain will be complete and link—block—link will pass on the motion. The block is hung in the end of an arm in which it can slide, and all that is required is to move the arm sideways while the link pieces are at rest in the proper position. This is shown in the diagram below.

28. In a machine such as the Analytical Engine, consisting of so many distinct trains of motion of which only a few would be in action at a time, it may be easily conceived how useful this application of the principle of Chain is. It helps to realize, too, another important principle largely adopted, viz., to break up every train of motion as far as possible into short courses, the last step of each furnishing a mere guide for a fresh start in the mechanism from the driving power. Of course the link could be broken and restored also by any of the “Directive Cards” mentioned above. The interposition of such links would also be used to save the cards from the wear and tear unavoidable if they were used for the actual transmission of any force.

29. I hope that I have now given some idea of the methods used for the general control of the engine, and shall pass on to illustrate, as well as I am able, some of the details of the machine. It is not to be supposed that I have mastered all these myself; nor, had I done so, would it be possible for me to make them intelligible in the course of a Paper, but some idea of them I hope to convey.

30. The machine consists of many parts. I have found it easier myself to regard these parts as so many separate machines, driven by the same motive power and starting and stopping each other in every possible combination, but otherwise acting independently, though with a settled harmony towards a desired result. When that idea has been reached, it seems easy to imagine them all brought close together, grouped in the positions most convenient.

31. Many general plans have been drawn. Plan No. 25, dated 6 August, 1840 was lithographed, others followed. The fact is, that what suits one part best does not suit another, and the number of possible variations of the parts renders it difficult to settle which combination of the whole may be the best for the general plan

32. A part of the machine called “The Store” has already been mentioned. It would consist of a number of vertical columns to receive the “given numbers” and those arising in the course of the calculations from them.

33. In the example already mentioned seven columns would be used; perhaps for a first machine twenty would do, with twenty-five wheels in each; each wheel might have a disc with the digits 0 to 9 engraved on its circumference, but this is not absolutely necessary. In act, the whole machine might be constructed without a figure anywhere except for the printing.

34. The “Directive Cards” would put the column selected to receive a “given number” into gear with a set of racks through which the “given number” (expressed on its card) would be conveyed to the Store column, each wheel being moved as many teeth as in the corresponding place of the number.

35. One revolution of the main shaft would be sufficient to put a “given number” on a column of the Store, or to transfer it from the store to some other part of the engine.

36. The action of the “directive card” in this case is to raise the selected column so that its wheels should be level with a corresponding set of racks, and thus brought into gear with them. Each column of the Store would require its own “directive card.”

37. At the top of each column of the Store would be a wheel on which the Algebraic symbol of the quantity could be written, and on the top of those columns assigned to receive the intermediate results this would also be done; though at first these columns would be at zero.

38. There would also be a wheel for the sign + or −. Drawings and notations for such sign wheels exist, and how far the operations of Algebra may be exhibited has been discussed.

39. The Mill is the part of the machine where the quantities are operated on. Two numbers being transferred from the Store to two columns in the Mill the two are put into gear together through racks, and the reduction of one column to zero turns the other the exact equivalent, and thus adds it to the other. Supposing there to be with each wheel a disc with the digits 0 to 9 engraved on its edge, and a screen in front of the column with a hole or window before each disc allowing one figure only to be seen at a time; during the process of addition the digits will pass before the window just as in counting till the sum is reached: thus if 5 is added to 7, the 7 will disappear and 8, 9, 0, 1, pass before the window in succession till 2 appear. At the moment when 9 passes to 0, a lever will be moved, thus recording the necessity of a carriage to the figure above; the carriage is made subsequently, and for the Analytical Engine a method of performing the carriages all simultaneously was invented by my father which he called “Anticipating” Carriage.

40. When two numbers are added, carriages may occur in any or every place except the last; where the wheels pass as just described from 9 to 0, a carriage arises directly; in those places where the figure disc comes to rest at 9, no carriage occurs, but one of two things may happen—if there is no carriage to arrive from the next right hand place, the 9 will not be changed; but should one be due, not only the 9 must be pushed on to 0, but a carriage must be passed on to the next place on the left hand, and if there happen to be a succession of 9's, they will all have to be pushed on. Working with twenty five places of figures there can be no carriage ever required in the last place, but there may be in any one, any two, any three, &c., up to twenty-four places, where a carriage may arise directly and the same up to twenty-three places where the presence of 9's may indirectly cause it.

41. Now immense as is the number of these two sets of combinations, they can be successfully dealt with mechanically by the principle of “Chain” and indeed every single combination as it arises is presented to the eye. There is a series of blocks for each place, the lower block is made to serve for the two events. The upper one has a projecting arm, which when moved circularly engages a toothed wheel and moves it on one tooth affecting the figure disc similarly. It rests on the lower block which moves it up and down with itself always. After the addition is completed, should a carriage have become due and the warning lever have been pushed aside, it is made (by motion from the main shaft) to actuate the lower block and throw it into “Chain,” when this is raised (again by motion from the main shaft) it raises the upper block which thus effects ordinary carriage; but supposing no carriage to have become due, there will be at the window either a 9 or some less number. The latter case may be dismissed at once; as a carriage arriving to it will cause no carriage to be passed on. Should there be a 9 at the window the warning-lever cannot have been pushed aside, but in every place where there is a 9 another lever, again by motion from the main shaft comes into play and pushes the lower block into “Chain”; not, of course, into “Chain” for ordinary carriage, but into another position for Chain for 9's, so that should there come a carriage from below, the Chain for 9's will be raised as far as it extends and effect the carriages necessary, be it for a single place, or for several, or for many. Should there be no carriage from below to disturb it the Chain remains passive; it has been made ready for a possible event which has not occurred. A certain time is required for the preparation of “Chain,” but that done all the carriages are then effected simultaneously. A piece of mechanism for Anticipating Carriage on this plan to twenty-nine figures exists and works perfectly.

42. When a large number of places of figures is being dealt with, the saving of time is very considerable, especially when it is remembered that multiplication is usually done by successive additions.

43. Another plan for carriage has also been contrived and drawn. It is obvious that there is no necessity, when there are many successive additions, to make the carriages immediately follow each addition. The additions may be made one after the other, and the carriages having been warned or even actually made on a separate wheel in each place as they arise, can all be made in one lot afterwards; more machinery is required, but the saving of time is very considerable. This plan has been called “Hoarding Carriage,” and thoroughly worked out.

44. It is interesting to note that Hoarding Carriage is seen in the little machine of Sir Samuel Moreland invented in 1666, and probably existed in that of Pascal still earlier.

45. Now it may happen in addition that two or more numbers being added together, there may not be room at the top of the column for the left hand figure of the result. This would usually happen from an oversight in preparing or arranging the cards when space should be left; but it might so happen that the calculation led, as mathematical problems sometimes do, through infinity. In either case a bell would be rung and the engine stopped; or if the contingency had been anticipated by the mathematician, fresh directive cards previously prepared might be brought into play.

46. One addition would be executed in each turn of the main axis, the intermittent motions required being produced by cams on the main axis. These would be flat discs with projecting parts on them acting on arms with friction rollers at the end. Each cam would be double, i.e. have two discs; the projections on the one corresponding with depressions on the other. Such cams are easily made and fixed and adjusted, about six or seven are sufficient for addition. The illustration shows such a double cam, together with a “Chain” for throwing into and out of gear, as explained in item 27. This may or may not be wanted.

47. Subtraction is performed by the interposition of an additional pinion, which turns the figure discs the reverse way; the figures decreasing in succession as they pass the window, and the carriage arises whenever the 0 passes and a 9 appears. The same arrangement is applied to the 0's in subtraction as to the 9's in addition, and the same principle of “Chain”; indeed, the same actual mechanism serves for both, the change being made by the movement of a single lever. See the illustration.

48. In subtraction, when a larger is subtracted from a smaller number, there will be a warning made in the highest place for a carriage to a place above which does not exist, zero has been passed; the warning lever will ring a bell and stop the engine, unless the contingency has been anticipated and provided for by the mathematician.

49. Several ways have been worked out and drawn for multiplication. A skilled computer dealing with many places of figures having to multiply would make by successive additions a table of the first ten multiples of the multiplicand; if he has done this correctly the tenth multiple will be the same as the first, only all moved one place to the left and with a 0 in the units place. Using this table he picks out in succession the multiples required and puts them in the proper places, then adding all up gets his results, dispensing altogether with the multiplication table and doing nothing beyond addition. For the machine this way has been worked out and many drawings and notations exist for it.

50. Another way by the use of barrels has also been drawn. The way by succession additions and stepping is perhaps the simplest.

51. When two numbers each of any number of places from one up to twenty or thirty have to be multiplied, it becomes necessary, in order to save time, to ascertain which has the fewest significant digits; special apparatus has been designed for this, called “Digit Counting Apparatus.” The smaller of the two is made the multiplier. Both are brought into the Mill and put on the proper columns. As the successive additions are made, the figure wheels of the multiplier are successively reduced to zero; when this happens for any one figure of the multiplier a cam on its wheel pushes out a lever which breaks the link or “chain” for addition, and completes that for stepping; so that the next revolution of the main axis causes stepping instead of addition, and that being done the links are changed back and the successive additions go on.

52. By this process the multiplier column is all reduced to zero; but if need be there can be another column alongside to which it may step by step be worked on—anyhow, it stands on record in its own column in the Store.

53. Multiplication would ordinarily be performed from the highest place downwards, and from the decimal point onwards; so that the result would be complete to the lowest place of decimals; but, of course, would contain the accumulated error due to cutting off the figures beyond in each quantity operated on. As, however, there would be a counting apparatus recording the successive additions, which at the end of the multiplication, would give the sum of all the digits of the multiplier, the maximum possible error would be known, and if thought advisable, a correction ordered to be made for it; for instance, the machine might be directed to halve the total of the digits, and add it to the last figures of the result wherever cut off.

51. Division is a more troublesome operation by far than multiplication. Mr. Merrifield in his report has called this “essentially a tentative process,” and so it is as regards the computer with the pen; but as regards the Analytical Engine, I do not assent to it.

55. As, however, he considered the striking part of a clock a tentative process, while I do not, the difference might be one of definition of a word, and I only notice it as maintaining that the processes of the engine are only so far tentative as the guiding spirit of the mathematician leads him to make them.

56. Division by Table and also by barrels has been thoroughly drawn and worked out—the process by successive subtraction also. The divisor and dividend being brought into the Mill, the successive subtractions proceed and their number is recorded; when the correct figure has been reached, the subtraction is thrown out by “Chain” and stepping caused.

57. There is no trial and error whatever. Some additional machinery is required for this and more time is occupied, but the result is certain; the engine stops of necessity at the right figure of the quotient, and gives the order for stepping and so on to the end.

58. For the extraction of the square root a barrel would be used, but the ordinary process might be followed step by step without a barrel.

59. Counting machines of sorts would perform important functions in the general directive. Some would be mere records of the progress of the different steps going on, but others, of which the multiplier column may serve as a sort of example, would themselves act at appointed times as might be previously arranged.

60. This principle of “Chain” is used also to govern the engine in those cases where the mathematician himself is not able to say beforehand what may happen, and what course is to be pursued, but has to let it depend on the intermediate result of the calculation arrived at. He may wish to shape it in different ways according as one or several events may occur, and “Chain” gives him the power to do it mechanically. By this contrivance machines to play simple games of skill such as “tit tat too” have been designed.

61. Take a simpler case where the mathematician desired to deal with the largest of two numbers arrived at, not knowing beforehand which it might be. The numbers would have been placed on the two columns of the Store previously assigned for their reception, and cards would have been arranged to direct the two numbers to be subtracted each from the other. In the one case there would be a remainder, but in the other the carriage warning lever would have been moved in the highest place, which would be made to bring an alternative set of cards, previously prepared, into play.

62. I have not been quite able to accept Mr. Merrifield's opinion as to the “capability of the engine.” He says: “Its capability thus extends to any system of operations or equations which leads to a single numerical result.” Now it could furnish not only one root, but every root of an equation, if there were more than one, capable of arithmetical expression, and there are many such equations. It could follow the processes of the mathematician be they tentative or direct, wherever he could show the way to any number of numerical results. It is only a question of cards and time. Fabrics have been woven requiring several thousand cards. I possess one made by the aid of over twenty thousand cards, and there is no reason why an equal number of cards should not be used if necessary, in an Analytical Engine for the purposes of the mathematician.

63. There exist over two hundred drawings, in full detail, to scale, of the engine and its parts. These were beautifully executed by a highly skilled draughtsman and were very costly.

64. There are over four hundred notations of different parts. These are, in my father's system of mechanical notation, an outline of which I had the honour to submit to this Association at Glasgow in 1855. Not many years ago I was looking over one of my own drawings with a very intelligent mechanical engineer in Clerkenwell. I wished to get motion for some particular purpose. He suggested to get it from an axis which he pointed to on the drawing. I answered, “No, that will not do; I see by the drawing that it is a ‘dead centre.’” He replied, “You have some means of knowing which I have not.” I certainly had, for I used this mechanical notation. The system in whole or part should be taught in our Art and Technical Schools.

65. In addition to the above things there will shortly be available, as I have said before, the reprint of the various papers published relating to these machines, and a full list of the drawings and notations will be included.

66. I believe that the present state of the design would admit of the engine being executed in metal; nor do I think, as suggested by Mr. Merrifield, quantities and proportions would have to be calculated. Of course working drawings would have to be made—it would not be wise to commence any work without such drawings—but they would mostly be simply copies from the originals with such details as workmen want added. It would also be wise to make models of particular parts. The shapes of the cams, for instance, might be tried in wood which would afterwards suit as patterns for castings.

67. Mr. Merrifield doubts “whether the drawings really represent what is meant to be rendered in metal, or whether it is simply a provisional solution to be afterwards simplified.” I have no doubt that the drawings do represent what at the time was intended to be put into metal; but as certainly were intended to be superseded when anything better could be found. Very few machines indeed are invented which do not undergo modification. It is almost invariably the case that the second machine made has improvements on the first design. In such a machine as an Analytical Engine, this would be important; but no one ever stops a useful invention for fear of improvements. A gun or an ironclad, for example, has been scarcely made before superseded by something better, and so it must be with all inventions, though fortunately not at the same speed.

68. As to the possible modification of the engine (Chapter VIII. of the Report) I may say that I am myself of opinion that the general design might with practical advantage be restricted. The engine would be still very useful indeed, if made not quite so automatic; even the Mill by itself would, I believe, be extensively useful, if a printing or stereo-moulding apparatus were joined to it. Perhaps, if that existed, the wants of further parts such as the Store would be felt and supplied.

69. As to the general conclusion and recommendation (Chapter IX. of the Report) there is little for me to notice. I see no hope of any Analytical Engine, however useful it might be, bringing any profit to its constructor, and beyond the preparation of this Paper, and the publication of the volume I have mentioned as shortly to follow, there is little or no temptation to do more. Those who wish for such an engine would, I think, give it a helping hand if they could show what pecuniary benefit it would bring. The History of Babbage's Calculating Machines is sufficient to damp the ardour of a dozen enthusiasts.